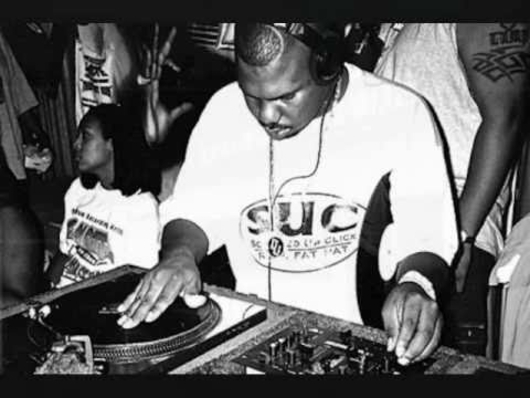

DJ Screw: tracing the genius of the chopped 'n' screwed pioneer

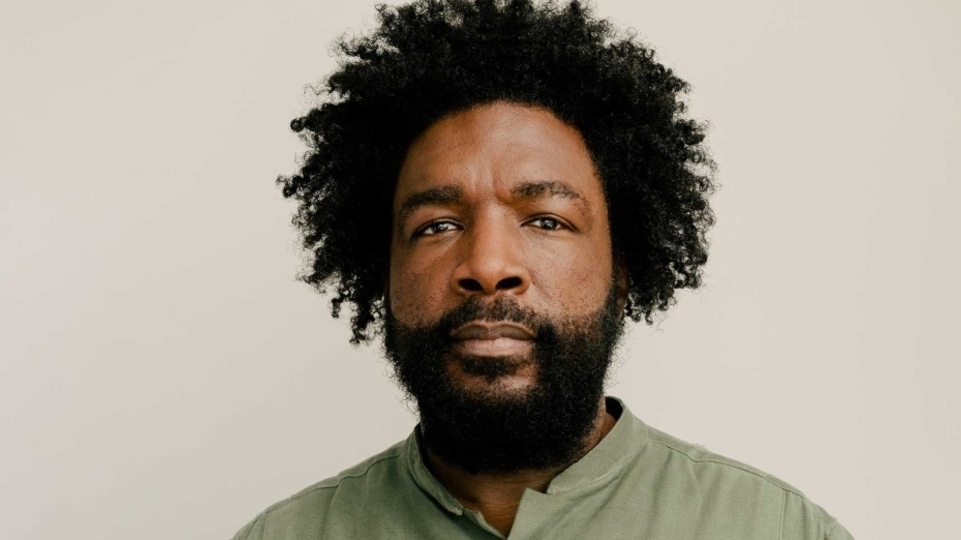

In his new book, Lance Scott Walker tells the story of DJ Screw, the maestro of Houston’s chopped ‘n’ screwed ‘90s rap scene. Here, Marke Bieschke speaks to the author about this unique moment in hip-hop history, and Screw's incredible legacy

Why did hip-hop slow down to a syrupy crawl in Houston, Texas, three decades ago? There are many theories, but Houstonians, who had come late to rap despite a rich musical heritage, passionately embraced the sound as uniquely their own. “It was heavy. It was enchanting. It was mystical,” writes hip-hop historian, Lance Scott Walker. “It made Houston feel different from anywhere else on the planet. In the mid-1990s, you couldn’t open a window in the big, hot city without hearing a car drive by playing slowed down hip-hop. You still can’t.”

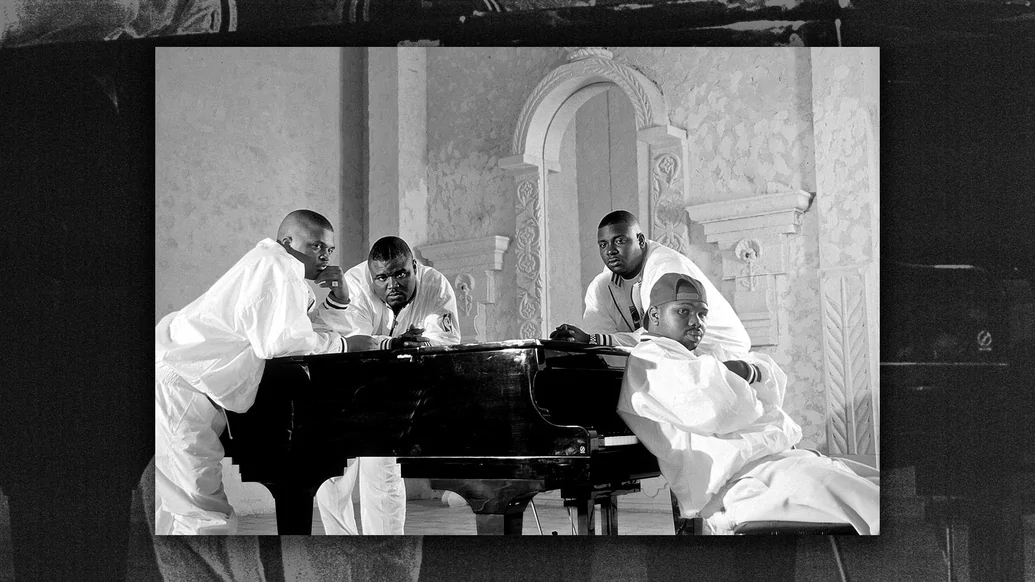

Fuelled by pimped-out car culture, home-rigged stereo equipment, a blizzard of mixtape cassettes and lean — the slurry of codeine-laced cough syrup and soda preferred by Southern partiers — Houston’s scene took pride in deep experimentation and even deeper bass. No one represented this moment more than DJ Screw, aka Robert Earl Davis Jr., the producer whose trailblazing, short life is captured in Walker’s just-released book, DJ Screw: A Life in Slow Revolution. An oral history composed of more than 130 interviews conducted over almost 20 years — including with his family, DJ mentors, dozens of MCs, like E.S.G., Big Hawk, Fat Pat. Lil’ Keke and Mike D, and breakthrough Houston rap groups Geto Boys and UGK — the book traces Screw’s genius from toying around as a child with his mother’s record collection to his untimely death in 2000, at the age of 29.

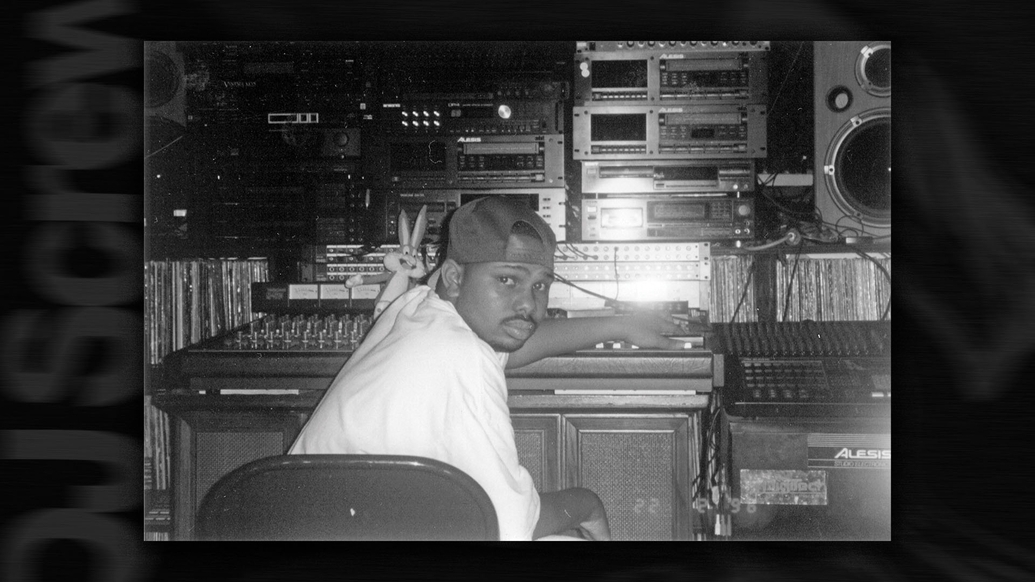

During those few years in between, Screw made hundreds, if not thousands, of mixtapes that sold like hotcakes from popped trunks on the street and through the metal bars of his front door. His chopped ‘n’ screwed sound, which ran tracks through a sluggish sonic blender only he could devise, defined Houston’s sound. He produced masterpieces like ‘Bigtyme Vol II: All Screwed Up’, the ‘3 ‘n the Mornin’’ mix series, and unofficial Houston anthem ‘June 27’ — an epic 35-minute freestyle that united many of the rappers and community members Screw would invite into his legendary Wood Room home studio for recording sessions that ran throughout the night.

This was all while he was cutting hair, running his own record store, DJing clubs and producing tracks for Triple Threat, Al-D and his voluminous group of collaborators, the Screwed Up Click. When he was found dead in his apartment, PCP, Valium, and codeine-promethazine were in his bloodstream, a lethal combination exacerbated by exhaustion and lack of exercise. But the image of the quiet genius who took things at his own pace was already fixed. “I wrote this book so people would see through myth to the real person — his life, his generosity, the community he built around him,” Walker says. “A lot of the conversation around Screw is about drugs, and that was certainly part of his life. But it was not what led his life. It wasn’t what motivated him or the source of his creativity.”

The gentlemanly Walker spoke with DJ Mag about that creativity, his book, and Houston’s rise to global hip-hop prominence.

You describe yourself as a white punk from Galveston, near Houston — but you’ve now written three books on Houston rap. What got you into documenting Screw and the scene?

“It really extends from my relationship with photographer Peter Beste. I go back to 1996 with him, when we were just kids. I was playing in punk bands and he was taking pictures. He left for his career, but by 2004 he had designs on coming back to Houston to do a project on Houston rap music. I was writing about nightlife for the Houston Chronicle newspaper and he said, ‘You’re a writer, why don’t you provide some words for me?’. We spent nine years collaborating on the Houston Rap photo book and I collected interviews for its companion, Houston Rap Tapes. I knew about Houston rap, I grew up with it. But in writing those books a new education began.

“The idea for the Screw book came while I was still in Houston, near the end of 2006. From the stories people told about him, I felt he was really special and there should be a book about him. I looked for one, maybe naively, but of course there wasn’t one. I really started building a library alongside everything else I was doing: a library about DJ Screw, interviews about DJ Screw. I knew it would be a long game, because he had so much depth. I didn’t mention it to anybody in the Screwed Up Click for a few years, until I had enough material to shape it into a book.”

The book is an oral history, but innovative in that you narrate many of the events being described to give us some colourful context of the time and place. Why did you choose the oral history format?

“DJ Screw is not here, we don’t have his voice directly in the book. Luckily we do have some documentation through interviews with magazines and radio of what he said, but we don’t get to hear his whole side of the story. We can piece it together through the recollections of people who knew him — and they can tell those stories much better than I ever could. The other part is, I’m a white writer doing this, all of this is going through a white filter. I talk about that in the preface; I really wanted to address that in the book, to deal with that fact directly. One of the ways to do that was to dial myself back and leave the storytelling in the hands of the people who lived it.

“Beyond that, Screw’s whole thing was about inclusiveness and giving people a platform to express themselves, to bring people into his world and shine his light into what they were doing. Whether they were a freestyler, an MC, or even someone who had no designs on rapping at all, it was more about him passing the microphone around and giving everyone permission to express themselves. The book is about community in that sense. I really wanted to highlight the community around Screw and take the same direction in making as much room for these voices as I could. That’s the way Screw did it — he passed the mic, and in a lot of ways the book is me passing the mic around.”

There are some terrific stories of the origins of slowed-down hip-hop and how Screw got started in the book, as well as real history of where he grew up, in the little town of Smithville, west of Houston, and in Houston’s famous Fifth Ward area. Were there any interesting stories of tracking people down?

“I had a wild ride trying to find most of the people in the book. It’s not easy getting in touch with many of the people, and it shouldn’t be easy, you should have to work for it. But it was really a journey to dig up the early DJs in his life, Darryl Butts and DW Sound. I felt like I really came up over the hill when I got those guys, because that was such a unique window into Screw’s early journey with turntablism. In both situations, it was generosity from those DJs that got him started. They were letting him get on their equipment early on. When you get those rare opportunities, it’s like a golden moment... I thought it was important to find them. It took years to get linked up with them.”

We’re still trying to wrap our heads around the fact that as a kid, he would take an actual screw and use it to scratch out the tracks on a record that he thought were bullshit. And the fact that his friends watched him do this and suggested that name, and it took off from there...

“It was pretty extreme. Every DJ prides themselves on being a great selector. I think that was Screw’s process of becoming a track deselector. Him saying, ‘I like what I like and I don’t want to have to remember to skip over that second track’. The funny part is that this was a point early on in his life when he’s not even DJing. It wasn’t like he had to look for record grooves under flashing lights in a club. This is at a point when he’s just a kid playing around with vinyl and exploring stereo equipment. Who knows what was going on in his head, but it sure was serendipitous to have that kind of idiosyncratic tic on his part. And then to have Shorty Mac pick up on it across the room and say, ‘Who do you think you are? DJ Screw?’”

And these were Screw’s mother’s records! She comes across as being this incredibly generous and strong person, who was also very driven herself, working three jobs to build the family its own home. Musically driven, as well — she was making 8-track cassettes of her own collection for friends early on, and selling them, too.

“Ida Mae was very enthusiastic about her record collection. When Screw was a young boy, they lived on the northside of Houston, in the Fifth Ward, which has a very long and vibrant musical history. There were several record stores in that area in the late ‘70s, and it was the right place at the right time for Ida Mae to pick up some incredible records. R&B, blues, disco, quiet storm-type soul was happening and jazz and zydeco, too, were there. So she showed him that you can have taste in music. She gave him an education that we see factoring into his mixes later on. Some of his mixes, you hear the songs and you wonder if those are records of his mother’s that he took with him.”

You can definitely hear that on ‘Tell Me Something Good’, where he’s playing with Chaka Khan, the Isley Brothers, and ‘Moments In Love’ by Art of Noise over a track by UGK. The book also tells a fascinating regional story of how hip-hop broke in a place very far from where things were originally happening. Screw and his friends had to hold tape recorders up to the radio to catch the rare rap song, and it took a children’s radio show, where the kids called in demanding more rap, to really get the Houston scene going. That’s a totally different Houston than we know now, as one of the global rap capitals. What was it like to tell Screw’s story knowing that Houston’s immediate future was so huge?

“It was thoroughly decontextualising [laughs]. Peter and I started documenting Houston rap in 2004, and then in the spring of 2005, everything breaks. Mike Jones, Paul Wall, Slim Thug, Chamillionaire... I was like, ‘Woah, this is crazy’. When I was growing up in Galveston, in 1992, the early version of the Geto Boys was hitting. This was before Scarface and Willy D joined, when they still spelled their name Ghetto Boys. For a local group to break like that was a big deal, hearing them on Galveston radio was huge. Even then, though, there wasn’t attention on the city, just the act. But in 2005-2006, suddenly all eyes were on Houston.”

Let’s talk a little about Screw’s technique. People obviously think of him as someone who slowed things way down, but he was also innovative in other ways. We love the story of when he auditioned for one of his early DJ gigs, he started trying to rewire the equipment so he could play things backward before they kicked him out. What are some things about how he worked that have stuck with you?

“It was interesting hearing about the progression of equipment that he experimented with. Right from the very beginning he was combining things in unique ways. Sometimes he only had access to one turntable, so he used a boom box to ‘crossfade’ into another song, or he would wire a boom box between two turntables to make a primitive fader. He would hook multiple tape recorders up together to chop parts of one song into other songs. He used to scratch in his own 808 basslines while he was cutting up records. It was years before he managed to put together some real money to spend on equipment. If you’re wiring stuff together like that, then Radio Shack is a huge step up.

“The more he added to his setup, the more he progressed. When he got his four-track and a microphone, he started figuring out how to slow things down. He didn’t do it when he recorded. He would record a master on the four-track and then slow things down on the dub. You’re losing a couple generations of sound right there. I have to feel that that was important to Screw. He had no interest in CDs, they weren’t long enough! Back in the ‘90s, CDs were only 50-60 minutes, that wasn’t enough for him. So he stuck with tapes, which were an important part of his sound. It’s interesting to think where he would have gone with newer technology. He may have just stuck to cassettes.”

What do you think it meant to him personally, and to his aesthetic, to slow things down so much?

“The way people explained to me how Screw moved through the world was that he moved through it slowly, he moved through the world with care. He didn’t rush his way through his day, he didn’t rush his way through his interactions with people, which is one of the reasons people feel so special about him. So many people felt like they were his best friend. That all converts right over to the music. He felt some kind of way about music. He wanted to take his time with it. He wasn’t working with typical remix tools, no separated tracks or stems. He was taking what was pre-existing and making it his own: ‘Let me slow this down a bit, let’s back this up a bit, I want you to hear it again, and really listen. Listen to what’s happening’. It was just his way of savouring the music.”

One of the big entry points for people to Screw’s music is the ‘June 27’ freestyle with D-Mo, Big Moe, Key-C, Yungstar, and everybody else who came through the Wood Room that day. It’s such a great document of Houston at that time.

“It’s fascinating because nobody knew they were making a classic. There were lots of people there that day, lots of people who recorded, there were other people in the room who weren’t necessarily on the mic. Screw never said, 'we’re going to stop after 35 minutes', he just kept going, they just kept going. I think it was indicative of the magic that happened in the Wood Room, with him at the helm, facing the wall and screwing around while everyone told their tales. That tape has a backstory, it has a prequel called ‘Dancing Candy’ — how many tapes can say that? It was made to be released on July 4th weekend, and when people start listening to a 35-minute song on a holiday, there’s a pretty good chance you’re going to start to hear it everywhere. It just caught fire. And has remained so popular that now June 27 is itself an unofficial holiday celebrating Screw, in Houston and in places around the world. That’s a real statement about what Screw still means to people.”

DJ Screw: A Life in Slow Revolution is out now via University of Texas Press. Find stockists at djscrewbook.com