François K's creative force

After nearly five decades in music, nobody could blame François Kevorkian for taking it easy. But that’s not in the France-born, NYC-based polymath’s DNA. Shortly after celebrating his 70th birthday, Bruce Tantum hears his story, and learns about the curiosity and drive that keeps him going

As soon as he sits down for a long conversation with DJ Mag, François Kevorkian, the NYC-based dance-music polymath universally known as François K, brings up a near-forgotten early-’90s party called Departure Lounge. It was the kind of no-rules freeform function where you might hear an experimental tone poem one minute, a pitched-down Hi-NRG disco chugger the next, followed by an Augustus Pablo dub rarity.

He praises the party’s selections — “it was so open-ended, and eclectic, in tune with the kind of things I would hear people like Gilles Peterson do in London,” he says — but that’s not the only aspect of the night he recalls. “That was the day I saw that someone had figured out how to use the headphone jack of a Urei mixer and send it to an effect box, and return that effect box on the input channel on the mixer,” he says. “So suddenly, that meant that the Urei had an effect send.”

It’s a minor anecdote in a lifetime full of major accomplishments, but Kevorkian’s recollection does a succinct job of summing up what’s kept him at the forefront of the clubbing universe for over 40 years. His focus has always been on both an all-encompassing view of what constitutes club music, and an engagement in what technology can do to bring that view to fruition. His work as a DJ, producer, label head and all-around musical adventurer mirrors the ongoing evolution of electronic music, from golden-age disco to deconstructed dub and back again; in other ways, he transcends it, existing in a quadrant of that universe that few others inhabit.

The list of his accomplishments is head-spinning — he’s been on mix and/ or remix duty for the wide-ranging likes of Arthur Russell’s Dinosaur L project, Kraftwerk, The Cure and Mick Jagger over the years, and co-founded the beloved Sunday tea dance Body & Soul, just to name a tiny subset of his accomplishments. (The man could write a book — “I’m working on it,” he confides.) And though he’s just turned 70, he’s still gleefully pushing the envelope.

“I became the only person to be a guest DJ at Paradise Garage, at The Loft and at Better Days. So that’s the trifecta.”

Kevorkian grew up in the suburbs of Paris, eventually finding his way in the early ’70s to the Alsatian city of Strasbourg, on the border of France and Germany. It was a university town with an active music scene — but it wasn’t where the real action was. Kevorkian, who had been drumming since adolescence, needed to be in the middle of things. “It was very sweet and comfortable in Strasbourg,” he says, “but it was very clear I was going to have to be at the origination point to become a participant in what I felt was so significant and happening. I was like Richard Dreyfuss in Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, single-mindedly drawn like a zombie to the mountain. He might lose everything, but he goes there because that’s his destiny. Well, that’s me in September 1975, arriving in New York, not even knowing where I was going to sleep the first night I was there.” (Nearly five decades on, his accent is now more Gotham than Gallic.)

With little money and no prospects to speak of, Kevorkian began to learn the terrain of the city’s bohemian underground. At one point, he needed a place to stay, and was looking to insert himself into a situation that would enable him to do so in some degree of style, so he answered an ad for the most expensive apartment he could find in the hopes that he could set himself up as a live-in gofer. The ad, as it turned out, had been placed by George Freeman, the owner of Galaxy 21, one of the city’s premier discos of the pre-Studio 54 era that boasted the pioneering Walter Gibbons as its resident spinner. Freeman made him an offer that would change his life. “He said, ‘I’m not looking for something like that’,” Kevorkian recalls. “‘But you’re a drummer? Well, I can hire you to play the drums in my club.’ And I was like, ‘You got it!’”

Up to this point, Kevorkian was largely unaware of disco — but he was a quick learner, setting up his kit on the dancefloor and playing along to Gibbons’ selections. (“It kind of drove him mad,” he recalls, “because from the DJ booth, he could hear my drums but with a delay.”) But after a few months, he came to the realisation that a change might be in order. Despite his plum gig, the competition for other drumming jobs in NYC was intense. “I figured if Walter could DJ, I could DJ too,” Kevorkian says. “I know how music is constructed, the arrangement and the structure and all that, so why don’t I give it a try? It’s a lot easier than carrying my drum kit around. And I had been inspired by seeing Walter play so many times. I’ll just show up with a little bag of records and get paid.” He bought a handful of records, just enough to put a short set together, and started going to auditions. “I basically got every job I ever auditioned for.”

One of those auditions, in October of 1977 was for New York, New York, a club on West 52nd Street that was positioned as the competition to the recently- opened Studio 54. “It was an upscale Midtown disco that was open every night of the week and packing them in, because this was like the time of disco fever,” Kevorkian recalls. “People were going out seven nights a week, a moment of collective madness that lasted for a year or so because of Saturday Night Fever. It didn’t have anything to do with the underground — it was a commercial gig — but it was a foot in the door.”

That foot in the door certainly paid off. Over the next few years, he played most of the clubs worth playing at, places along the lines of Newark’s Zanzibar and, yes, Studio 54. “And I became the only person to be a guest DJ at Paradise Garage, at The Loft and at Better Days. So that’s the trifecta.”

Around the same time as securing the New York, New York gig, Kevorkian was jump-starting his production career via tape edits, some of which were based on the work that Gibbons was performing at the club. (Kevorkian’s own knowledge of song structure, thanks to his background as a musician, didn’t hurt.) One of the best from that early era was ‘Happy Song’, a drum-break edit culled from a Rare Earth tune. Kevorkian put it together and hustled over to Sunshine Sound, a label specialising in such edits. “They paid me a little something every time the acetate sold, and it must have sold hundreds and hundreds of copies, because I made a lot of money at the time,” he says.

By the middle of 1978, Kevorkian had a meeting that would change his life. He had a friend at an independent New York label, and the two of them were invited by the label’s president to give their opinions on some music that the label was thinking of releasing. “I probably went into more details than I should have,” he says, “like, ‘Well, the strengths should be raised in this part, and you’d do better if you had that and this and that’. He asked my friend to leave the room, and then he said, ‘Well, I want to make a job offer right now. I’d like for you to A&R for our label starting next week.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, I’ll have to think about it’. I didn’t know what A&R meant! The label was Prelude Records, and by July 1978, I was being thrown into a studio, asked to do things.”

Right out of the gate, he was mixing ‘In The Bush’, produced by disco maestro Patrick Adams and credited to Musique. The song was a massive hit, and many more were to follow for the label — D-Train’s ‘Keep On’, Sharon Redd’s ‘Beat The Street’, Unlimited Touch’s ‘Searching To Find The One’ and The Strikers’ ‘Body Music’ among them. Taking on independent work as well — Yazoo’s ‘Situation’ and Robert Palmer’s ‘Pride’ are a couple of the early notables — Kevorkian was basically living in the studio. (“If you can call that living,” he says.)

“I got my first computer in 1984, I was connected to the internet and sending emails to people by mid-1985, and by late ’85, I was already running sequencer programs that controlled MIDI instruments.”

Eventually, the workload became so great that he felt he wasn’t able to give the time to Prelude that would enable him to give it his all — nor was he being compensated well enough by the label to turn down the outside work. “On the other hand, I had every label from the UK chasing me,” he says, “because this was when all these pop groups were trying to get credibility from dance music, trying to use some of that excitement from the underground and dance music energy. I felt that I could strike out on my own — and I did.” Kevorkian has been a freelancer ever since.

If the previous few years were a blur for Kevorkian, the rest of the ’80s were perhaps even more so, to the point where he had to retire from spinning to devote more time to the studio. Forming his own company, Axis Productions, the next few years saw him working on everything from ‘Snake Charmer’ (a collaboration between Jah Wobble, U2’s The Edge, Holger Czukay and Jaki Liebezeit, and an early example of Kevorkian’s frequent dives into deep dub) to mainstream acts like U2 and Diana Ross. Amid that whirlwind, his exploration of the intersection between music and technology was beginning to deepen.

“I got my first computer in 1984, I was connected to the internet and sending emails to people by mid-1985, and by late ’85, I was already running sequencer programs that controlled MIDI instruments. I figured out how to synchronise those things to existing tapes,” he says. “I was able to go into the studio and do sessions, adding all these overdubs — added synthesisers, MIDI drum machines, all that. In 1985, that was pretty cutting-edge. And by 1987, I had already gotten into digital editing.”

That year, he opened Axis Studios, a state-of-the-art space located in the Studio 54 building, a four-room world-class facility that over the next years served as one of Manhattan’s top recording spaces. The work, both within Axis’s walls and without, was pouring in, and one of the biggest assignments of Kevorkian’s career came in 1989. “Depeche Mode had approached me before, but I had passed on doing mixes for ‘Behind The Wheel’ because I was too busy with other things. But by late ’88, we had a meeting and they decided to get me to do one single, and if that was successful, I was going to mix the rest of the album.”

That single’s mix met the band’s approval. “By late ’89, we had completed an album called ‘Violator’,” he continues, about as nonchalantly as one can be about an LP that sits on a slew of 'Best Album Ever' lists. “And I guess that kind of changed my life, because the record has probably gone on to sell 25 million copies, so I assume that was a reasonably successful project for all concerned.”

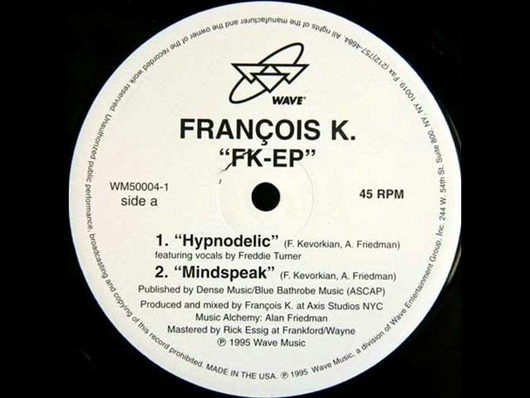

But it wasn’t all big-name acts – he worked on more personal projects as well, many of them released on his own Wave Music, the prolific label he founded in the mid-’90s. Wave, like Kevorkian himself, was genre-agnostic, rooted in club music but with a sound that ranged from the billowing depths of Fluid X’s ‘Change’ to the soaring emotionalism of Soul Music’s ‘Fade’ to the percussion-led sunshine of Natural Flavors’ ‘Sun Juice’ to Kevorkian’s own ‘FK-EP’, a revered release with a sound distilled by the name of its lead track, ‘Hypnodelic’.

In the early ’90s, the DJing bug bit once again, and Kevorkian was soon spinning at top-tier clubs like Ministry Of Sound and Tokyo’s Yellow; he also embarked on the Harmony Tour, a 1992 odyssey that saw him playing 10 back-to-back gigs in Japan with Larry Levan, not long before the Paradise Garage pioneer passed away. It was during this era that he began to apply his tech-friendly ways to the spinning arts by travelling with several boxes of digital audio tapes and DJing with a pair of DAT players. “Which meant that I had two thousand songs that were not on vinyl,” Kevorkian explains. “If I wanted to play a certain track, I had it.” That may not sound like a lot now — but for the time, it was. “In ’92, maybe people in Goa were pretty big on DAT tapes,” he says, “but in general, I was kind of anticipating the curve a little bit.”

He added CDs to his repertoire a few years later. “I’d carry a book with 100 or 150 custom CDs,” he recalls, “and two or three boxes of DATs, which consisted of probably five or six thousand songs. I wanted to have whatever I wanted to play available — it could be a drum & bass track. It could be an old classic gospel record. It could be a jazz track. It didn’t matter. I had it.” Not surprisingly, keeping track of that many tunes without the benefit of a database proved difficult. “So I hired a programmer and paid him a large sum of money to build me a custom relational database. I had a tiny, tiny little micro-laptop, and the only function of that laptop was that.”

Things got even easier when he met the team from Native Instruments in the early 2000s. 2018, along the way featuring a staggering range of guests that takes in dubstep progenitor Mala, the dub explorers of Basic Channel, Tribal Winds’ Antonio Ocasio and Bauhaus co-founder David J. (That last one was admittedly a bit of an anomaly, but Kevorkian is nothing if not open to experimentation.)

“We were giving people a playground, an opportunity to congregate safely, in a comfortable space where they could express themselves and their love for music and dancing without feeling constrained.”

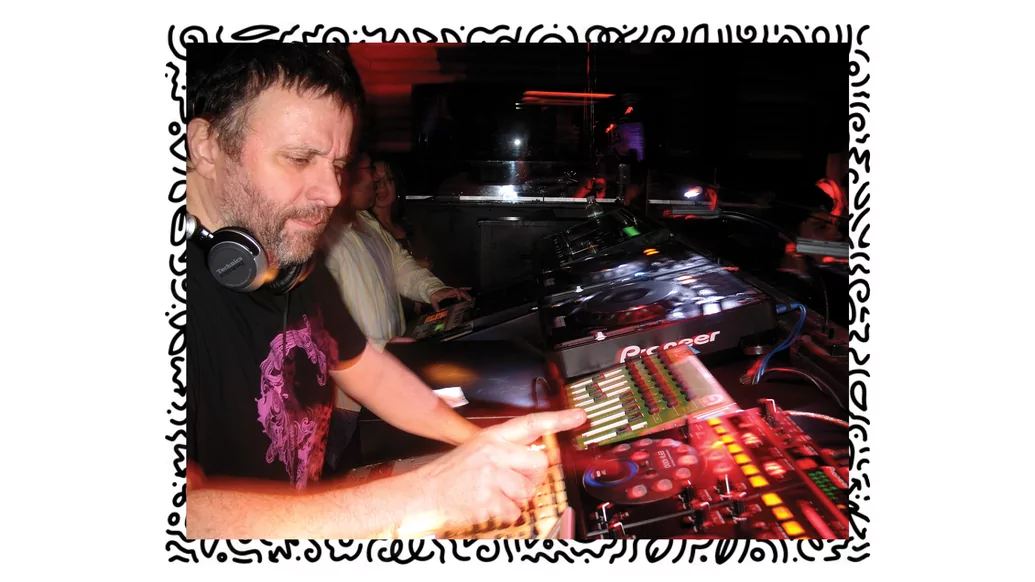

Much of Kevorkian’s current focus is on his live-stems mixes and sets, excursions that see him deconstructing tunes, many of them classics like Gino Soccio’s ‘Dancer’ and Frankie Knuckles’ ‘Baby Wants To Ride’, into spiralling, dubbed-out spectres of their original form. “I am now playing with a system that allows me to have two full decks of eight tracks each,” he explains, “so I can do a full remix on the fly, live, improvised in front of you. This may not seem like a really big deal, but you know, after 40 years of pushing play to let the same version be heard for the umpteenth time, it brings a whole different element to what I do. I can mould it to the moment and adapt and change and stay very creative, sharing the inner part of who I am with you, as an audience.”

Towards the end of the conversation, Kevorkian talks about his listening habits in a way that illustrates his continued musical curiosity, even after nearly five decades in the business. “I am not shy in admitting that a lot of what I find interesting is far more varied than just dance music,” he says, “and I find a lot of the creativity may have migrated to some places like the UK. I hear so much good stuff coming out of the London jazz scene, for instance. Inflo, Sault, so many of the records that come out on Brownswood — they’re absolutely beautiful. Not to take away anything from maybe some of the more electronic and introspective works that I hear played by other people, but for me, what I just mentioned takes precedence because it incorporates more vocals and more far-reaching, well-realised productions. Little Simz, all sorts of things. It depends on what mood I’m in — sometimes I’ll just go and research African records for a week. But there’s so much out there and I’m never completely up to date on everything.” We suspect he does better than most DJs one-third his age.

On 6th January, Kevorkian threw himself a 70th birthday bash in a well-appointed boîte in downtown Manhattan. The venue was on the swanky end of the nightlife scale, but this was a real-deal party, with a trio of New York club lifers — DJ Spinna, Justin Strauss and Jeannie Hopper — on the decks, Eric Kupper and D-Train’s Hubert Eaves III on live keys, and Kevorkian himself laying down a live-stems set. Attended by NYC clubbing royalty past and present, it served in part to honour the indelible mark that the birthday boy had made on the musical lives of everyone present — but just as much, it felt like a celebration of all that was yet to come.