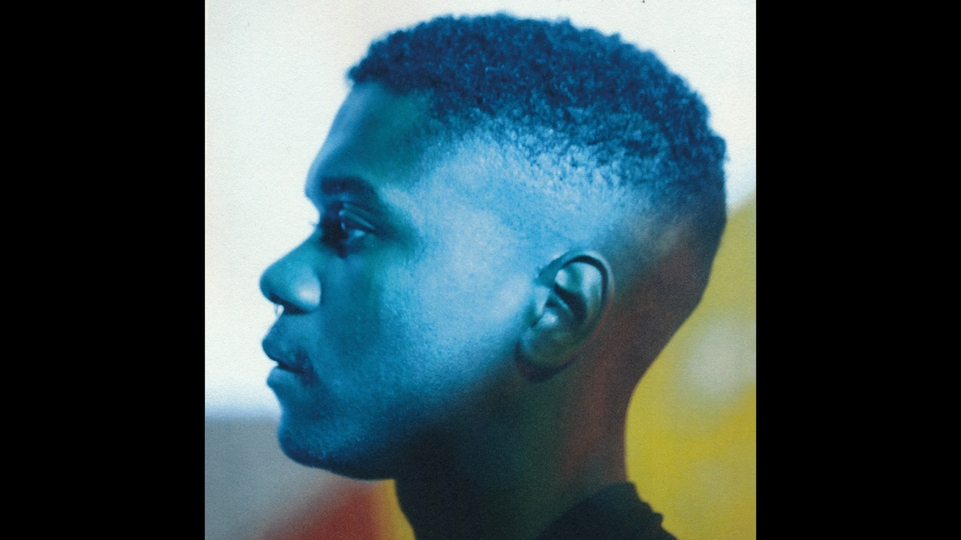

Get to Know: Nazar

From: Angola and Belgium

For fans of: Deena Abdelwahed, Fatima Al Qadari, Loraine James

Three tunes: ‘Arms Deal’, ‘Airstrike’, ‘Ceasefire’

“In my high school class, I was the only person that was openly against the regime,” says Nazar. His family fled Angola for Belgium before he was born: his father, a general in the opposition army, was targeted by the Angolan regime during the civil war. Growing up in Belgium, he was seduced by electronic music. When he and his family moved back to Angola, to be reunited with his father, they faced a different reality.

“I always got into debates with teachers and classmates,” he remembers. “My first teacher in Angola was very pro-regime. Towards the end of my last year of high school, they were talking bullshit about the dictator because he was losing power. It was all propaganda.”

After the assassination of rebel leader Jonas Savimbi in 2002, a post-war tension hung in the air. During the war, kuduro, an energetic new electronic dance genre, developed. Shaped through sampling Caribbean carnival tracks, the genre travelled with Angolan immigrants to Portugal and grew into a heralded underground sound, most visibly to Western dance music audiences today through crews like Lisbon-based Príncipe.

For Nazar, though, kuduro felt “too upbeat” to reflect Angola’s daily reality. He took his discontent and channelled it through music. Nazar created a sound he calls “rough kuduro”, first heard on his debut EP, ‘Enclave’, released on Hyperdub in late 2018. “It was an idea for [an] album, and Hyperdub took the six best songs for ‘Enclave’,” Nazar explains. “I was like, ‘Shit, I’ve got to make more music’.”

What planted the seeds for ‘Guerilla’ — his debut album, also on Hyperdub — was a show he played at London’s Corsica Studios with American DJ and producer DJ Haram. “I couldn’t care less about the precision of space back then,” he mentions. “After that show, I started thinking about the structure of my album.” ‘Guerilla’ distils collective trauma into rough kuduro, and examines how the terror of the Angolan civil war was heard as much as felt: with floor-threatening bass, darkened sirens, aeroplane engines and chopped-up vocals spoken through intercoms.

Though no one in Nazar’s family was killed during the war, his parents were directly involved. His mother left home at 16 years old to join the revolution, meeting his father along the way. Much of the album is based on his father’s 2006 wartime journal, Memorias de Um Guerrilheiro. Nazar’s mother also makes a vocal appearance on ‘Guerilla’.

“Women in war have a very crucial role in the fight,” Nazar says. “That’s why I wanted to make sure that the voice of my mother could be heard.” Nazar believes that Angolans pass down their stories orally for a reason: to include the humour that comes with having experienced unimaginable terror. “No one I know in Angola can tell me a story that doesn’t involve laughter, because they’re just happy and grateful that they survived,” he says. “It was much easier for me to translate this into music — it’s kind of like therapy.”