GREG WILSON'S DISCOTHEQUE ARCHIVES #19

A guide to dance music's pre-rave past...

We've drafted in Greg Wilson, the former electro-funk pioneer, nowadays a leading figure in the global disco/re-edits movement and respected commentator on dance music and popular culture, to bring us four random nuggets of history; highlighting a classic DJ, label, venue and record each month.

Whether it be introducing The Twist into London nightlife as a dancer, helping break R&B, bluebeat, ska and psychedelic records as a DJ, or contributing to the first Glastonbury Fayre, Jeff Dexter consistently had his finger on the pulse of popular culture.

Lambeth-born in 1946, his pre-teen love of records, coupled with a flair for fashion that spawned his interest in tailoring, proved a potent combination. His sharp style, both with regards to music and the clothes he wore, meant he slipped hand-in-glove into the burgeoning mod scene, befriending another young mod, Mark Feld, who later found fortune as T. Rex’s Marc Bolan.

Whilst still well underage he managed to obtain membership at the popular West End dance hall The Lyceum. On his first visit he witnessed the debut DJ appearance of Ian ‘Sammy’ Samwell, best-known as the songwriter of ‘Move It’, Cliff Richard’s breakthrough hit in 1958, credited as one of the UK’s first authentic rock & roll records.

Dexter and Samwell would become firm friends and the teenager would arrive early at the club to practise his dance moves. When it first arrived in the UK, The Twist, popularised by Chubby Checker’s 1960 single of the same name, was deemed vulgar, with the 15 year old Dexter barred from The Lyceum for pioneering the dance there. Ironically, he was invited back and hired as resident dancer when The Twist blew up in popularity – he even made it onto a Pathé newsreel.

His dancing would take him to mod-hotspot The Flamingo, one of the venues where he and Samwell would host record nights, as well various ballrooms and nightclubs in the West End and events in the big hotels.

In 1966 the Jeff Dexter Record & Light Show began at Tiles on Oxford Street, one of Soho’s defining clubs, where he’d play bluebeat, ska, soul, R&B and the new psychedelic records, both American and British. He’d attend UFO’s hippie happenings and occasionally play records there too, but Tiles would be his main club residency during the Swinging London era, with both night and lunchtime sessions. When Middle Earth took up the hippie baton following the closure of UFO, Dexter took his place as DJ alongside John Peel, who would later, as a result of his long-running Radio 1 show, become a national institution whilst Dexter faded into relative obscurity.

Dexter gave up DJing in the early-‘70s, concentrating his energies on managing the band America, fondly-remembered for their worldwide hit ‘A Horse With No Name’, bringing in his friend, producer Samwell, to work with him on the project.

Bronx-born Henry Stone had been active within the music business since his army discharge in 1947, setting up his own distribution company upon moving to Miami the following year. Throughout the ‘50s he’d establish a number of labels and could claim to be instrumental in James Brown’s emergence.

With his hugely successful distribution company taking emphasis during the ‘60s, it would be in the ‘70s that Stone made his greatest contribution to black/dance music, forming TK Records, named after Terry Kane who built Stone’s studio in 1972, which would become world-famous for its ‘Sunshine Sound’.

Serendipity struck when Stone employee, vocalist/keyboardist Harry Wayne Casey (aka KC), embarked on a goldmine of a songwriting/production partnership with TK studio engineer Richard Finch, which would result in some of disco’s best-selling recordings, not least George McCrae’s ‘Rock Your Baby’ (1974), one of early-disco’s defining singles, hitting 10 million sales worldwide and reaching the summit in a dozen countries, the US and UK included.

Casey & Finch would achieve major success with their own group, KC & The Sunshine Band, topping the US chart a handful of times between 1975-79 with ‘Get Down Tonight’, ‘That’s The Way (I Like It)’, ‘(Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty’, ‘I’m Your Boogie Man’ and ‘Please Don’t Go’. Earlier releases, ‘Queen Of Clubs’ and ‘Sound Your Funky Horn’ found favour in British clubs, reaching the UK top 10 and top 20 respectively. TK releases were then issued in the UK on the Jayboy label – it wasn’t until 1977 that the TK imprint appeared here.

The company would boast a whole array of artists, consistently tearing up the dancefloor throughout the second half of the ‘70s, both via the main TK label and on subsidiaries like Sunshine Sound, Drive, Dash and Juana.

Bahamians, T-Connection would provide one of dance music’s great percussive workouts, the 1977 monster cut ‘Do What You Wanna Do’, whilst Jimmy ‘Bo’ Horne’s ‘Spank’ remains an evergreen disco standard, revitalized two years on by Began Cekic’s re-interpretation ‘Sixty-Nine/Change Position’, a cult underground cut. Peter Brown’s ‘Do You Wanna Get Funky With Me’ was a downtempo disco-funk favourite, Anita Ward took the infectious ‘Ring My Bell’ (1979) to #1 on both sides of the Atlantic, whilst percussionist Ralph MacDonald’s ‘Calypso Breakdown’ (1976) would feature on the best-selling ‘Saturday Night Fever’ soundtrack.

Following 1979’s ‘Disco Sucks’ backlash, TK ran into financial difficulties and was acquired by legendary music mogul Morris Levy, with Stone subsequently running the Sunnyview label Levy set-up, which put out contemporary releases with an electro slant, including Newcleus and Extra T’s, as well as selected TK back-catalogue under the Sunnyview Classics banner.

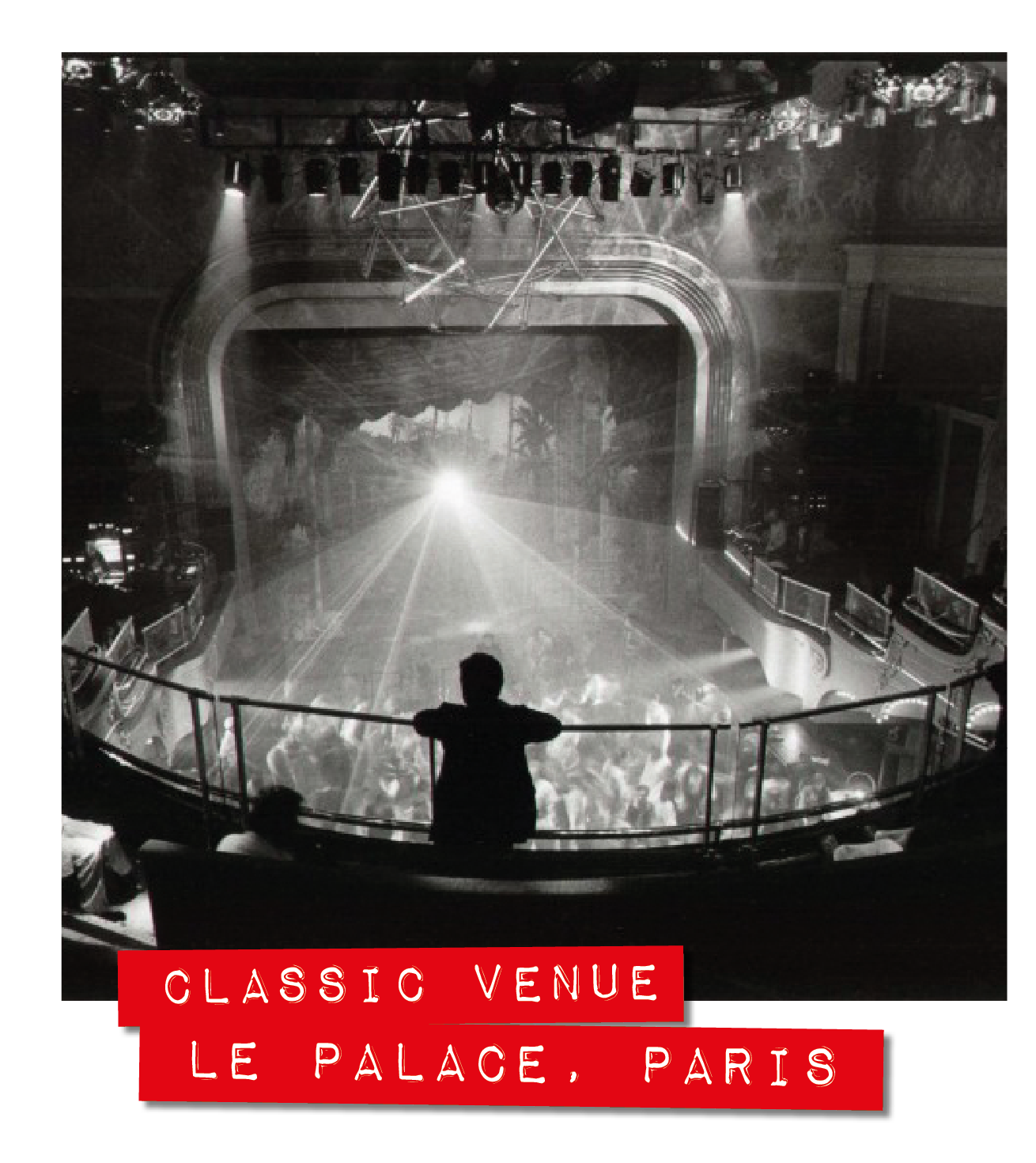

Le Palace arrived at the height of the disco era. Dreamed up by impresario, Fabrice Emaer, it became Paris’ most celebrated nightspot, operating an inclusive policy, albeit in an exclusive manner, attracting people from all walks of life, be it rich or poor, gay or straight, black or white – if your face fit you were through the door.

Built in 1895, the venue first acquired the name Le Palace at the turn of the 20th Century, serving as an esteemed music hall, a cinema and even an experimental theatre before Emaer’s 1978 acquisition.

Emaer had previously owned Le Pimm’s Bar from 1964, making it one of Paris’ most renowned gay nightspots. In 1968 he opened Le Sept, a restaurant complete with basement club space.

Le Sept’s flamboyant Cuban DJ Guy Cuevas championed funk and soul there, the venue described as the city’s ‘epicentre of disco’ with the proto-disco Philly Sound prevalent and a dancefloor filled with the mix of people Emaer wanted.

However, upon visiting New York’s Studio 54, he returned with a grander vision that required a sizeable space. Le Palace was purchased and he funnelled a small fortune into renovating the impressive yet decrepit old music hall. He wanted to create a hotbed of excess, and it proved to be the right club at the right moment. As with its illustrious NY predecessor, famous stars, artists and celebrities flocked through its doors to join the dance.

Le Palace was a revelatory experience with its kaleidoscope of sound, lighting, lasers, flashing neon, dry ice and confetti cannons. They later installed a huge mirror behind the stage, making the room seem even more imposing in size.

At the opening night, Grace Jones performed ‘La Vie En Rose’ atop a bright pink Harley Davidson, and the venue was immortalised in Amanda Lear’s ‘Fashion Pack’ (1979). A Studio 54-style selective door policy, which sought out beautiful or interesting looking people regardless of background, ensured the crowds were as diverse as Emaer’s previous club, whilst projecting an aura of exclusivity.

Cuevas would leave in the early-‘80s, disillusioned that the music he was expected to play had become too commercial. Emaer lost his life to AIDs in 1983, but not before he laid the foundations for what would become Le Palace’s famous ‘Tea Dance’, a staple within Paris’ gay community.

Le Palace would move into the house era, Laurent Garnier DJing there for the first time under his own name, whilst also hosting UK-based S-Express’ Pyramid parties. It would eventually close its doors in 1996 and since 2006 it’s served as a theatre again.

Recorded in Milan and released in 1982 on Italian label Zanza, ‘Dirty Talk’ was the first single by Italian Mario Boncaldo and Italian-American Tony Carrasco, AKA Klein & M.B.O. The track featured Italian singer Rossana Casale, but many DJs flipped the record, as with a number of early-‘80s dance tracks, preferring the instrumental versions.

It took off on the New York underground following DJ support from the likes of Larry Levan at Paradise Garage, Danceteria’s Mark Kamins and at David Mancuso’s Loft parties, with NYC label 25 West picking it up for US release. The track would reach #14 on the US Dance chart.

I played a part in its UK trajectory, which would take a significant twist in Manchester. It arrived at a time when seminal electro-funk tracks like Peech Boys ‘Don’t Make Me Wait’, ‘Planet Rock’ by Afrika Bambaataa & The Soul Sonic Force and Rockers Revenge’s ‘Walking On Sunshine’ were beginning to alter the sonics of dance music.

It was Harry Taylor at Manchester’s Spin Inn record store that sold me my copy of ‘Dirty Talk’. Whilst my main focus was the latest US imports, largely out of New York, Harry, who supplied numerous DJs on the gay scene, would sometimes pull out a European import that he thought might suit this electronic direction I was moving in. It was in this way the Zanza 12” came into my hands.

It was soon the biggest track at my club nights in Wigan Pier and Manchester’s Legend, with other DJs picking up on it, including Hewan Clarke, the resident at a recently opened club with a mainly student/indie clientele, The Haçienda, half a decade ahead of its acid-house golden era.

One night Hewan was playing ‘Dirty Talk’ when members of the band, New Order, who were co-owners of The Haçienda, came into the DJ booth to ask if they could borrow it to use as a reference for a track they were working on. This would turn out to be ‘Blue Monday’; subsequently the biggest selling 12” single of all-time.

The Italo disco duo would enjoy further success with singles ‘Wonderful’ and ‘The MBO Theme’ (released on Atlantic Stateside) but to nowhere near the same extent as ‘Dirty Talk’.

Carrasco would compose/produce their final single, ‘Keep In Touch’ (1986) alone, while Boncaldo put out two singles with the group MBO in 1987 including ‘M.B.O. Liverpool Theme’, recorded in the city.

I would be commissioned to re-edit ‘Dirty Talk’ in 2008, combining it with ‘Wonderful’ - the resulting version featured on my second ‘Credit To The Edit’ compilation the following year.

Written by Greg Wilson

Edited by Josh Ray

'Mr. Dexter' illustration by Pete Fowler

Check out the previous Discotheque Archives here