How Air’s ‘Moon Safari’ became an elegant masterpiece of '90s electronic music

Released in early 1998, Versailles duo Air’s debut album ‘Moon Safari’ was a gentle antidote to the wave of French Touch at the time. With an emphasis on melody and mood, it became a ubiquitous soundtrack to the end of the 20th century, and still sounds inspired today. Here, Ben Cardew explores its legacy

This feature was originally published by DJ Mag North America in 2019

So much electronic music is dominated by rhythm: the 4/4 stomp of techno; the woozy pulse of dubstep; the clattering breaks of jungle and drum and bass. However, some of the best electronic music — from Kraftwerk to Daft Punk, Masters at Work to Underground Resistance — is based on a wonderful understanding of melody, creating those hooks that stick in your head at the end of the night when the legs have been reduced to a mushy pulp.

To this list we might add Air, the silkily nerdish duo from Versailles, who combine classical melodies with heady atmospherics, Serge Gainsbourg-esque élan and more than a hint of sex. Their music laid a framework for a generation of magenta-hued chill–out bands to idle out of the woodwork in their wake.

1998’s ‘Moon Safari’ was Air’s debut album, and, to date, their defining act. If you were young at the end of the 1990s and had anything more than a passing interest in electronic music you will have heard it, soundtracking dinner and after parties, school runs, chill-out rooms and 1,001 stodgy TV dramas. So ubiquitous did ‘Moon Safari’ become, in fact, and so many terrible bands did it inspire, that Air became almost persona non grata in the 2000s, their career hobbled by the intolerable omnipresence of their debut.

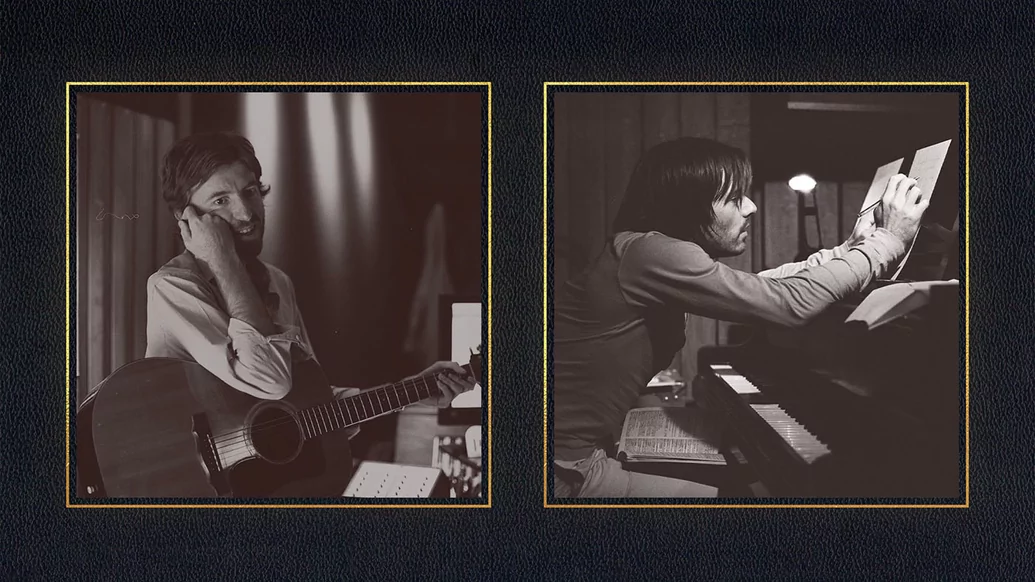

And yet, when you consider everything Air had against them, it was a minor miracle they even made their breakthrough. Air weren’t particularly fashionable, for a start. Even in the mid ’90s, when Parisian music was riding the sizzling wave of French Touch, band members Nicolas Godin and Jean-Benoît Dunckel resembled more the architecture and maths students they had so recently been than the fashionable men around town their peers aspired to.

“It was the late 1990s and Paris suddenly had this incredible electronic music scene: all these clubs were opening up. I didn’t get to go to all the parties, though, because I was generally at home with my wife taking care of Solal, our baby,” Dunckel told The Guardian in 2016. “We were poor. I knew our livelihood depended on Air being successful.”

Air dreamed to be different, both visually and sonically. There was nothing edgy or unconstrained about the band, no whiff of rebellion to get the heart strings pounding, and little in the way of beats to dance to. Most of all, as a stylistic decision, Air chose to be quiet: a gentle Gallic nuzzle to the ear rather than a voluptuous bear hug.

‘Sexy Boy’, the first single to be taken from ‘Moon Safari’, is typical of the duo’s individualistic approach to songwriting, marked by an androgynous, indistinct vocal. "If we’d sung ‘sexy girl’, it would have been a disaster. ‘Sexy Boy’ felt different,” Godin told The Guardian. “The song was about who we wanted to be; we weren’t handsome when we were younger; our friends always had more success with girls.”

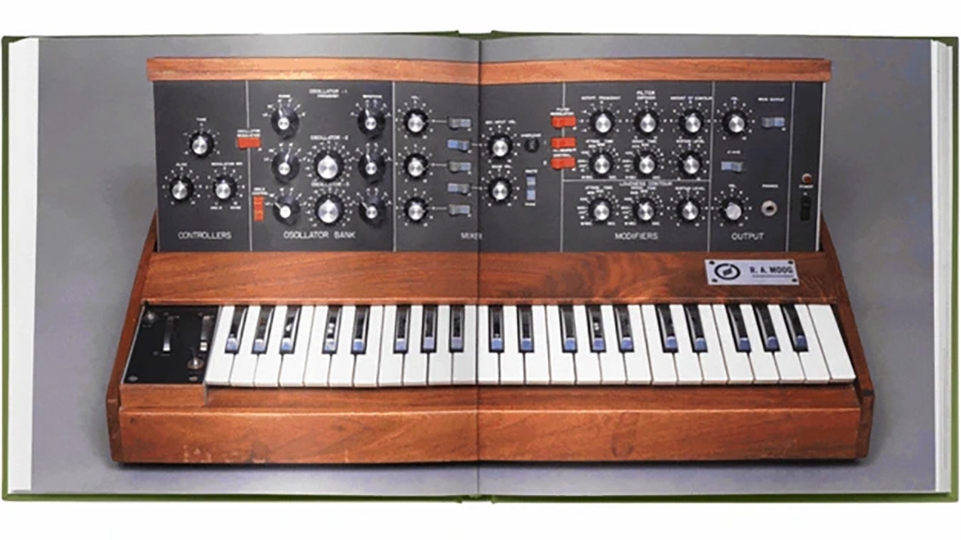

So Air were big, unfashionable softies in a musical decade marked by innovation, ambition and noise. It would have been easy for Air to spanner together disco samples and filters to create a French House tune that would temporarily captivate the Parisian nightclubs. What Air did was to rely on melody and timbre to make their hugely elegant point. ‘Moon Safari’ was the epitome of this, the album’s 10 tracks forming a closed loop of such melodic brilliance and galactic ambience that listening to anything else afterwards felt like scraping muddy boots on a silk-lined boudoir. These are melodies that stick in the brain like glue, suspended in zero G by a velvety ambience of Fender Rhodes, clavinet, vocoder, strings and Moog.

Countless articles have been written about the recording of ‘Moon Safari’, and you can see why: the album pulled off the difficult task of sounding both futuristic and retro, its mixture of vocoders, synths and Serge Gainsbourg bass resembling a 1960’s vision of the gilded future, a combination best heard on the impossibly lush string and vocoder jam ‘Remember’.

Album opener ‘La Femme d’Argent’ is a wonderful example of Air’s insouciant melodic brilliance. The track also features stunning bass work, sporting the kind of bassline that carries the song on its back and leaves you singing in the shower.

Air were classically trained musicians who wore their hearts on their sleeves. The atmosphere of their music was balanced by the human emotion in their songwriting. ‘You Make It Easy’, a glittering highlight, spoke of the magic of falling in love, Beth Hirsch’s vocal soaked in emotion, while ‘New Star in the Sky (Chanson pour Solal)’ seemed to inject a whole galaxy of love and wonder into four tightly-packed lines with the ultra efficiency of a haiku.

And it was this, ultimately, that separated ‘Moon Safari’ from the music that came in its wake. Among the trends that the album inspired were an international Serge Gainsbourg revival, a renewed interest in film soundtracks, and the career of Sofia Coppola, with the band scoring her directorial debut The Virgin Suicides the year after ‘Moon Safari’s’ release. You can hear the album’s influence in the work of acts like Kid Loco, Bent, Röyksopp, Crustation, Tim “Love” Lee, Cibo Matto, Sébastian Tellier and more. But what few of these acts seemed to grasp, in their search for ever lusher melodic beds, was at the centre of Air’s artifice was a beating heart. Rather than the clatter of drums, this was the rhythm that ‘Moon Safari’ moved to.