How Beastie Boys’ ‘Ill Communication’ set a benchmark for '90s eclecticism

The release of Beastie Boys’ fourth album on 31st May 1994 signalled a new era not just for the New York trio, but for music at large. Fusing sampladelic hip-hop, punk and unruly rap rock with brazen stylistic experiments, it set a refreshingly eclectic tone after a decade of genre tribalism, and altered perceptions of the group on both sides of the Atlantic. Here, Ben Cardew learns how

‘Ill Communication’ wasn’t the biggest Beastie Boys album; that medal goes to the multi-million selling ‘Licensed to Ill’. Nor was it the New York trio’s coolest or most radical-sounding when placed next to the sampladelic collages of ‘Paul’s Boutique’, or the underground sensation that was ‘Check Your Head’.

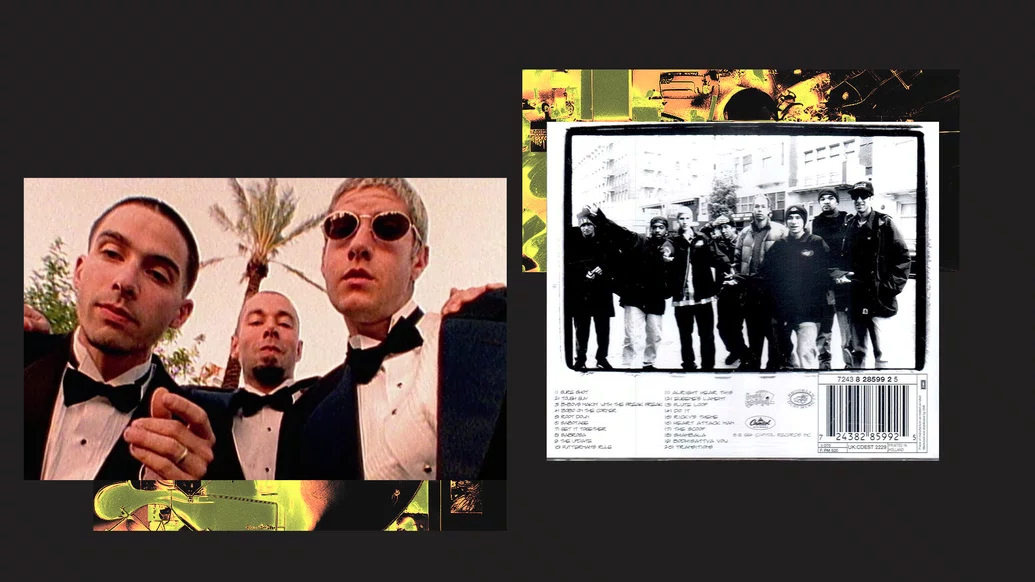

It was, however, in many ways, more important than all that. Released on 31st May 1994, Adam ‘Ad-Rock’ Horovitz, Michael ‘Mike D’ Diamond and the late Adam ‘MCA’ Yauch’s fourth album marked the moment when everything finally clicked into place for them. Across its 20 tracks — including singles ‘Sabotage’ and ‘Sure Shot’ — Beastie Boys transformed from bratty rappers into credible mainstream stars. In doing so, they helped shape the music of the ’90s, unleashing a spirit of DIY eclecticism that resonated through several of the decade’s greatest records.

‘Ill Communication’ was a bit of a slap in the face when it first appeared on record store shelves, at once naggingly familiar and utterly unexpected. Here, the sampling adventures of 1989’s ‘Paul’s Boutique’ converged with the skate crew cool of 1992’s ‘Check Your Head’ and the unruly rap rock of 1986’s ‘Licensed to Ill’, culminating in an uncharacteristically mature and genuinely varied suite that alchemised and expanded on their previous stylistic experiments.

Incorporating their own live instrumentation along with jazzy strings and flute samples, smooth double bass and rolling percussion, the trio sound more welcoming than ever on ‘Ill Communication’, their well-rounded grooves luring you in while disparate cultural references (from Lee Dorsey to Pat Ewing) act like invitations to a special kind of club.

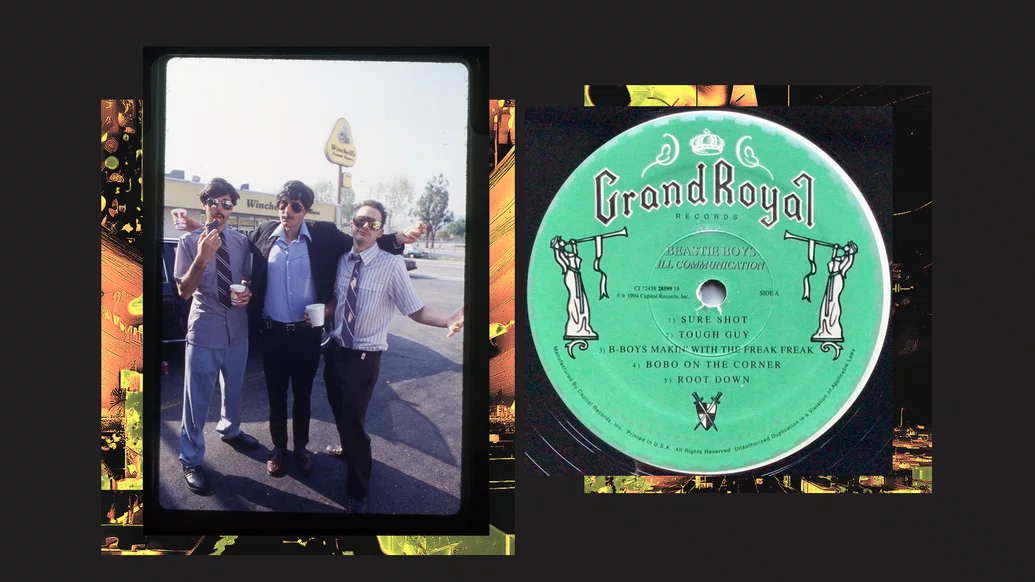

On top of its hip-hop foundations, the album includes callbacks to the band’s earliest days as snotty punk rockers (‘Tough Guy’, ‘Heart Attack Man’), as well as references to jazz rock (‘Bobo On The Corner’, whose stretched out wah-wah grooves point to the influence of Miles Davis’ ‘On the Corner’), Latin-influenced lounge funk (‘Sabrosa’), Tibetan Buddhist monks (‘Shambala’) and, of course, rap rock (the eternal ‘Sabotage’).

“They could pretty much do anything around that time,” says DJ Hurricane, Beastie Boys DJ for their first four albums. “Everything was working. And when everything is working, you can do what you want to do.”

“You just try stuff out and see if it sticks,” Hurricane adds of the band’s working methods. “If you don’t try it out, you don’t know if it’s going to work or not. Once you try it out and it works, you go with it.”

This eclecticism made ‘Ill Communication’ very Beastie Boys and very ’90s. The 1980s, by and large, was a decade of staunch musical tribes, where bands of distinct sonic identities stood staring at each other over cavernous stylistic divides. This eased a little in the rave years and early ’90s, thanks to groups like De La Soul and Primal Scream, but there was still a general belief that bands should stick to what they were good at.

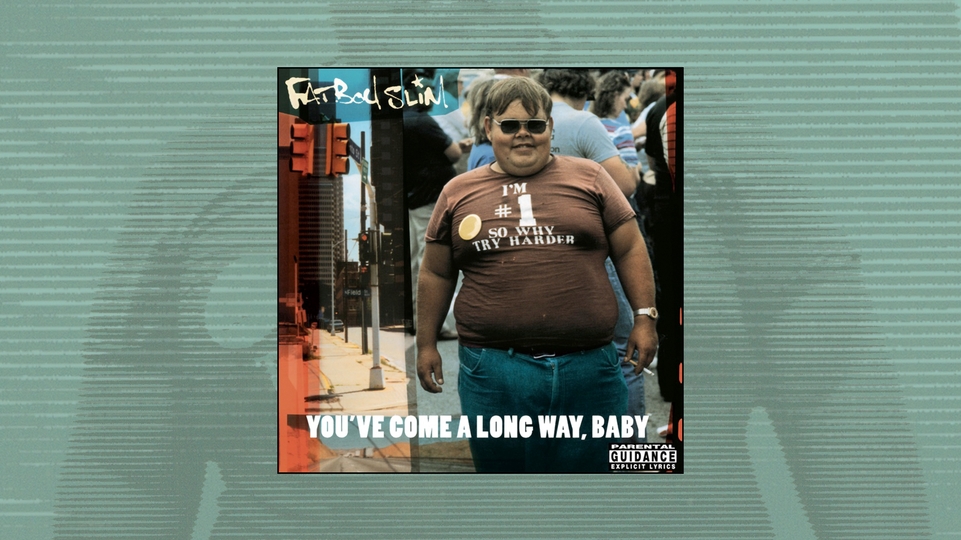

‘Ill Communication’ was a line in the sand, a record held together by vibes, mood and attitude more than generic signifiers that helped to change this straight-jacketed way of thinking. From ‘Ill Communication’ you can see a clear line to Beck’s wonderfully scattergun ‘Odelay’, The Chemical Brothers’ fiercely varied ‘Dig Your Own Hole’, or Fatboy Slim’s ‘You've Come a Long Way, Baby’, three records that are emblematic of the 1990s.

Dave “Switch” Taylor, the British producer who would later work with Beastie Boys on ‘Don’t Play No Game That I Can't Win’ from their eighth studio album ‘Hot Sauce Committee Part Two’, says that ‘Ill Communication’ “educated my ears to a whole new level of musical diversity”. “It was definitely an outlier,” he explains, “kind of unexpected and in a way unsatisfying. It demanded a lot, is how I felt, but that just made it more worthwhile once you digested it properly.”

British and American audiences probably saw Beastie Boys in slightly different musical contexts. In the US, they sat somewhere between alternative music and the jazzier side of hip-hop; shortly after the release of ‘Ill Communication’, they were one of the headline names on the 1994 Lollapalooza tour, alongside The Smashing Pumpkins and A Tribe Called Quest, whose leader Q-Tip had appeared on ‘Ill Communication’ single ‘Get It Together’.

In the UK, meanwhile, Beastie Boys were a lingering influence on — and early supporter of — what came to be known as trip-hop, thanks to their association with James Lavelle’s Mo’ Wax label, which was, for a few years in the 1990s, about the most fashionable company you could keep.

Lavelle was a staunch supporter of Beastie Boys, telling Phat magazine in 1993: “I'm into the total energy of the Beasties and that whole kind of skate thing. I want that energy and total madness surrounding the whole idea.” The respect was mutual: Mike D told Relax magazine in 2000 that what Lavelle is doing with Mo’ Wax “is very substantial and rich in variety, that makes his work so original”.

There were numerous crossovers between Mo’ Wax and Beastie Boys. An instrumental version of ‘Ill Communication’ track ‘Bodhisattva Vow’ was included on Mo’ Wax’s 1996 compilation ‘Headz 2’, its thoughtful hip-hop grooves fitting neatly in between songs from DJ Krush, Massive Attack and Nightmares on Wax. Meanwhile, Mike D guested on Mo’ Wax supergroup Unkle’s debut album ‘Psyence Fiction’, appearing on the track, ‘The Knock (Drums of Death Part 2)’. Money Mark, the keyboard player on every Beastie Boys album from ‘Check Your Head’ onwards, would release his debut album on Mo’ Wax, with ‘Mark's Keyboard Repair’ riding the ‘Ill Communication’ wave to No. 35 in the UK charts.

Bizarrely, for a group who had built their second album almost entirely around samples, the key to ‘Ill Communication’ and its effortless eclecticism is the Beastie Boys’ own musical skills. ‘Check Your Head’ had been the band’s first record since their 1982 debut EP ‘Polly Wog Stew’ to feature them playing their own instruments — Horovitz on guitar, Diamond on drums and Yauch on bass. They were, by their own admission, not exactly master musicians. “We sucked really bad, at first,” Horovitz said in an Amazon Music documentary to mark 25 years of ‘Ill Communication’ in 2019. “But we figured out a way to do it for ourselves.”

A year of intensive touring following ‘Check Your Head’ helped, too. “They really got better as we toured,” says Hurricane. “The more shows we did, the better they got at their instruments.”

“We went on tour playing everywhere,” Horovitz explained to Amazon Music. “Mike’s on the drums and I know what he’s going to do next. And I’m playing guitar and I know what Mark’s going to play and Yauch. So after a year-long tour, instead of taking a break, we just went back in the studio because our studio was really fun.”

“Being with them in the studio was a proper grin,” says Taylor. “They literally ‘Pass The Mic’ [a song on ‘Check Your Head] – like ‘Gimme it, gimme it, I wanna!’ while the beat is on in the room, just shielding it with their hands – incredible. And there were well funny stories, jokes – very special people.”

You can hear this beautifully light musical telepathy throughout ‘Ill Communication’. ‘Sabotage’, the rap rock fusion that would go on to be a game-changing hit, is the kind of esoterically inevitable song that could only be created by people who are really happy playing together, its grooves hitting in all the strangest places.

Elsewhere, the group sounds absolutely in the funk pocket on songs like ‘Root Down’, while Yauch deserves a special mention for his immaculate double bass playing on songs like ‘Sabrosa’. “MCA was unbelievable on bass,” says Hurricane. “He played electric and stand-up bass. And he made it look easy.”

What the Beasties couldn’t play, they sampled. Though sparse compared to ‘Paul’s Boutique’, the samples deployed on ‘Ill Communication’ are perfectly judged for maximum impact. ‘Sure Shot’ makes once-heard-never-forgotten use of a lilting flute from Jeremy Steig’s 1969 song ‘Howlin’ For Judy’, while ‘Get It Together’ rides gracefully along a distorted clip of The Moog Machine’s ‘Aquarius / Let the Sunshine In’ from the ‘Switched-On Rock’ album of Moog covers.

In each case, the line between sample and live instrumentation is delightfully thin. You feel that if Beastie Boys had learned to play flute, they would definitely have conjured up something like ‘Howlin’ For Judy’; if they were to borrow a Moog, it probably would have resulted in the funked-up fuzz of ‘Aquarius / Let the Sunshine In’.

‘Ill Communication’ was a huge hit, the band’s second No.1 record in the US and a top ten album around the world. “I wasn’t surprised,” says Hurricane, “because I was there when ‘Licensed To Ill’ dropped and sold 10 million. I was there when ‘Paul’s Boutique’ dropped and didn’t sell. And I was there when ‘Check Your Head’ did much better. So when ‘Ill Communication’ dropped I was expecting it to be a big record. I listened to the album, the way they put it together, and I expected it to be a big record.”

Lollapalooza, Hurricane adds, “was one of the most explosive tours I did with the Beastie Boys”. “I don’t know if there was a better tour. Lollapalooza was so competitive, the crowds were incredible, every day... We were really at our peak, in terms of live performances, on that tour. We were really kicking ass on that tour.”

‘Ill Communication’ didn’t just re-establish Beastie Boys musically, it also helped to create a new image for the band, thanks to the success of Spike Jonze video for ‘Sabotage’, in which they parody 1970s crime drama shows in period wigs and fake moustaches.

The ‘Sabotage’ video was absolutely huge: MTV seemed to have it on permanent rotation and it even influenced the iconic opening scene of the 1996 film adaptation of Trainspotting. You could pretty much guarantee, in the mid 1990s, that if you hung around at a British festival long enough, someone would turn up dressed like the cop protagonists of the video and they would be very drunk indeed.

This visual refresh — Beastie Boys as jovial jokers, with a knack for setting a trend — went hand in hand with the band’s musical renaissance, wiping clean the brash, annoying collective memory of ‘Licensed To Ill’ from the public’s heads. No longer would Beastie Boys be the crude punk rock rappers who became tabloid villains. From ‘Ill Communication’ onwards, they became synonymous with a kind of eclectic musical cool that you could take home to meet your parents.

In other words, after ‘Ill Communication’, Beastie Boys could do whatever the hell they wanted, and their fans would embrace it in large numbers, whether that be a Jean-Jacques Perrey-inspired album of laid-back instrumentals (1996’s ‘The In Sound from the Way Out!’), a rambling dub-inspired collaboration with Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry (1998’s ‘Dr. Lee, Phd’) or weird electro pop hip-hop (‘OK’ from ‘Hot Sauce Committee Part Two’).

It was all just Beastie Boys music — brilliantly so. And ‘Ill Communication’ was at the tangled, eclectic and overwhelmingly warm heart of it all, the cornerstone of a fantastically unlikely musical odyssey.

“Beastie Boys stand alone,” says Hurricane, who is currently working on a 30th anniversary reissue of his 1995 album ‘The Hurra’ with Beastie Boys producer Mario Caldato. “They are too hard to copy. They are a standalone group slash band in hip-hop. A unique group of guys.”