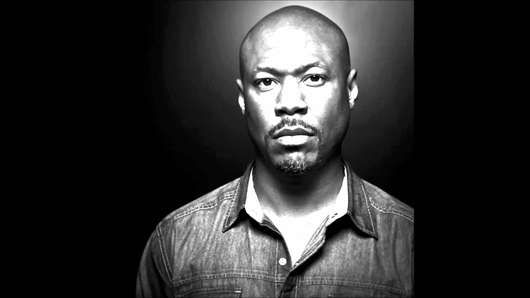

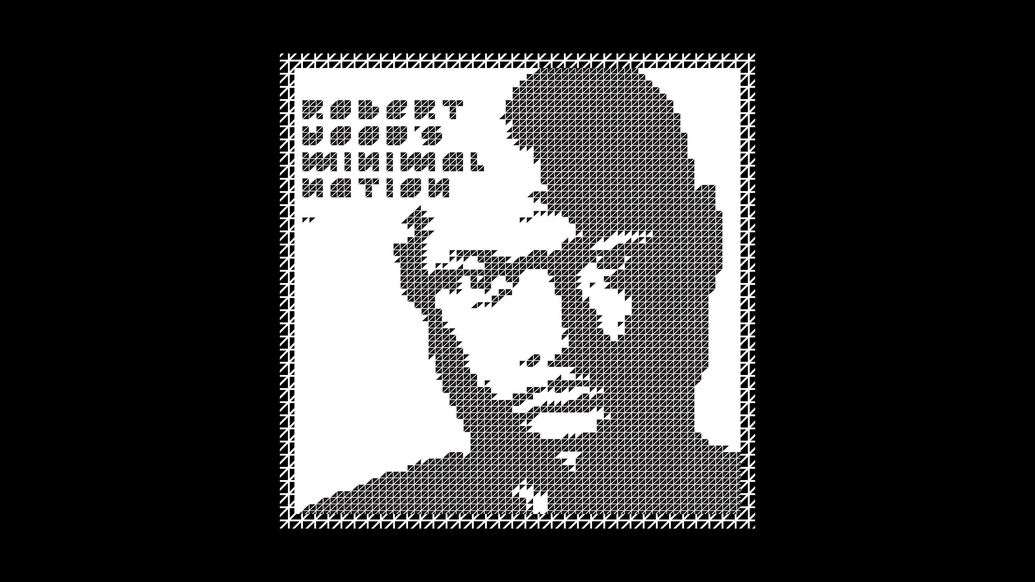

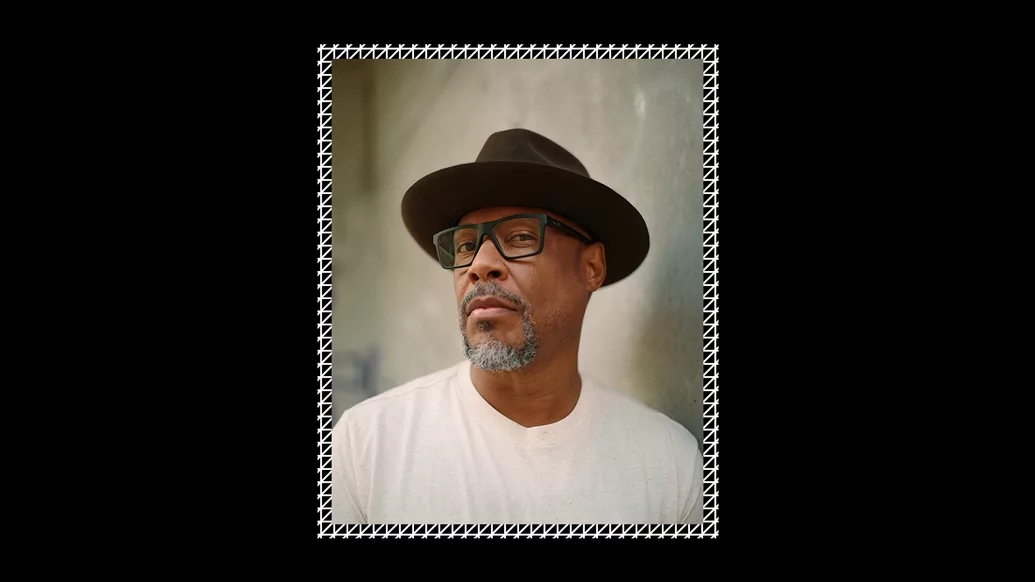

How Robert Hood’s ‘Minimal Nation’ became the defining work of minimal techno

Released on 1st January 1994, Robert Hood’s ‘Minimal Nation’ saw the pioneering Detroit producer distil techno’s futuristic intent, creating a stripped back, raw and percussive record that became a defining work of the minimal techno sound. 30 years later, and with minimal more prominent than ever, Ben Cardew speaks to Hood about the album’s enduring influence

It is fitting that Robert Hood's ‘Minimal Nation’ was released to the world on 1st January, 1994. Rarely has a record so clearly signalled a new page in musical history, a year zero shift in intention that we are still feeling the effects of today. ‘Minimal Nation’ is a New Year’s Resolution of a record, a promise to cut down on all excess and get right down to the essence of living, as it gets down to the lifeblood of techno music.

“For me, that record was life changing,” Hood explains down the phone from Alabama when he speaks to DJ Mag in December. “I literally felt the earth shift when I heard certain records, and that gave me building blocks or a blueprint to what I would do with my music.”

The clue, of course, is in the title. ‘Minimal Nation’ is the defining work of minimal techno, later known simply as ‘minimal’, a genre tag that remains omnipotent 30 years on. Hood wasn't the first techno producer to arrive at this combination of stripped down, grinding loops and percussive layers. He names Robert Armani, Rhythim Is Rhythim's ‘Drama’, Adonis’ ‘No Way Back’ and K’Alexi Shelby’s ‘My Medusa’ and ‘Vertigo’ as precursors to the sound, while his erstwhile partner in Underground Resistance, Jeff Mills, was working in similar territory at the time. But ‘Minimal Nation’ named the phenomenon and, arguably, perfected it.

In doing so, Hood catapulted techno into a new era. When the genre first emerged in Detroit back in the ‘80s, it sounded futuristic and funky, with an element of repetition balanced against an almost songwriter-y craft. Detroit producers were inspired by George Clinton, Kraftwerk and Depeche Mode — artists with songs, in other words. You can hear this in early tunes like Model 500's ‘No UFO’s’, which has something in the region of a traditional song structure.

On ‘Minimal Nation’ Robert Hood took techno’s futuristic intent and distilled it, inspired by musical influences as diverse as Detroit’s Jit scene and funk breakbeats. “The best part of the record was always the breakdown, in funk and soul music. As far as I could tell in the neighbourhood I grew up in, going to house parties, basement parties, I saw what that did to people if you extended that break,” Hood explains. “That's how hip-hop was born, from the break. It was always the ‘Get Down’ part where you find that pocket and you just make it a repetitive loop. Stay in the pocket and watch it put people in a trance.”

Important as this was, Hood says that his influences weren’t just musical; he also lists “minimal art, Italian furniture, design, Italian lamp design” as inspirations for ‘Minimal Nation’. Early video games were an influence too. “I remember when Space Invaders came out. I was working at a toy store at the time. And I could hear this repetitive ‘bum bum bum’, bass-y, sort of alien, Space Invader rhythm as the aliens were coming down,” he says, with a laugh. “I'm borrowing these elements. And it was creating something deep in the recesses of my mind. And, unbeknownst to me, as I began to make music, what was stored in my mind began to come out.”

From furniture design to music, minimalism is often pegged as a cold, rather inhuman, movement, where intellectual and stylistic constraints win out over raw emotion. For ‘Minimal Nation’, however, the opposite was true. Hood was inspired by a desire to return to a more human touch in electronic music, in reaction to the early ‘90s rave scene.

“Detroit was so progressive, one of the most progressive cities at that time,” he says. “The rave scene was getting oversaturated to me — the drugs and all that... It was becoming so commercial and so watered down, that I wanted to take it back to its essence,” he explains.

“It's not like I was setting out to make a minimal project. It was just that this is how I felt, this is what moved me. And so I felt that, quite possibly, if it moved me it could maybe move other people.”

The ‘Minimal Nation’ formula is simple. Start with one basic synth riff, add a pounding kick drum, then modulate, tweak and filter the melody while adding and subtracting layers of percussion. It sounds simple, perhaps, and in many ways it is. You're not, typically, dealing with more than four elements at any point in the song, so what you see is very much what you get. It is electronic music in its bare bones, not reduced but enhanced in its minimalism.

Fittingly, Hood made ‘Minimal Nation’ with a limited tool kit, borrowed and bought from other Detroit musicians, including a “$50 four-track mixer” that he bought from Mike Clark (aka Agent X), Jeff Mills’ Yamaha DX100 digital synthesiser and “pawn shop equipment”, including a Roland SH101, a Roland Juno 2 and a Yamaha QY20.

The set up reflected Hood’s situation: he told Red Bull Music Academy in 2019 he was “one step away from being homeless” at the time he recorded ‘Minimal Nation’. “It was a very challenging time,” he tells DJ Mag today. “I didn't have much money and was finding it hard to make ends meet, to pay the rent and to eat. I had those times where, ‘Hey I got a couple of dollars. I am either going to buy a corny dog or a beer.’”

Despite this, Hood says that writing the record came “like breathing”. “It was just so organic. It just flowed out so easily,” he explains. “Everything pretty much was done in one take: no multi tracking, just straight to DAT as I felt it. And no redos.”

Perhaps the most unexpected influence on ‘Minimal Nation’ was Detroit’s Jit scene, a stylised form of dance that is often considered a sister to Chicago footwork. “A lot of people don't know this but the record was really made for jits, the dance style that came out of Detroit back in the late ’70s, early ’80s,” Hood explains. “It really wasn't made for the average, so-called, ‘techno enthusiast’. It was made for people who understood that dance [Jit]. It was really made for Detroit and I don't think I've ever told Jeff [Mills] or Mike [Banks] this or anybody else that I can remember. But that was the mindset: stripped down, no nonsense, straight to the point dance grooves. Just rhythm tracks for the most part.”

And Detroit’s Jit scene loved ‘Minimal Nation’ right back. “I had just finished a mastering session and was getting ready to leave,” Hood relates. “And Theo Parrish and Kenny Dixon Jr., Moodymann, they come in and we were talking a little bit. And Kenny Dixon is telling me, ‘Yeah, this motorcycle club, Friday, Saturday nights, the guys, they jit to ‘Minimal Nation’... I was elated to hear that: it all came into fruition.”

‘Minimal Nation’’s sonic simplicity makes it sound like it should be easy to reproduce. But — as the failings of so many later minimal records have shown — making something this straightforward is incredibly difficult. It’s magic, even, how Hood coaxes so much out of so little.

The secret lies in the funk. ‘Minimal Nation’ balances rock hard beats with a fluidity of rhythm that calls back to George Clinton and James Brown. Listen, for example, to the central synth riff in ‘Museum’: its off-kilter roll and slightly freaky modulation stinks of P-Funk’s slack-but-precise musical swagger.

“It's just so important that you find a pocket, and once you found the pocket, once you found that groove, you have it,” Hood explains of his production style. “It's not like I was setting out to make a minimal project. It was just that this is how I felt, this is what moved me. And so I felt that, quite possibly, if it moved me it could maybe move other people.”

Hood talks about James Brown’s concept of The One, in which he emphasised the first beat in the bar rather than the more traditional down beat, an innovation that filtered through musical history. “Him being James Brown, being Bootsy Collins’ teacher, and Bootsy Collins taking that aesthetic and connecting it to George Clinton and Parliament / Funkadelic, to Ohio Players and to Earth, Wind and Fire and so on, it’s all important,” Hood says. “And with rave music, I felt like, gradually, it was losing its groove. Let’s shift it back to its foundation. And let's keep it on a solid foundation and never let it stray from there again.”

With such a limited musical palette, the use of reverb is hugely important in allowing ‘Minimal Nation’ to come alive. (You can hear this, in particular, in the subtle production tweaks towards the end of ‘Museum’ as the song builds towards its climax). For this, Hood was indebted to mastering engineer extraordinaire Ron Murphy, the go-to guy for Detroit’s producers.

“He suggested ‘Minimal Nation’ would have some delay and reverb when needed because I brought it in all dry,” Hood explains. “He [Murphy] was just as much a part of producing our records, in my opinion. He would always be very helpful in helping us with ideas.”

The impact of ‘Minimal Nation’ was vast. Older techno tunes were swept aside by a wave of darker, harder, weirder, more unsparing tracks, by the likes of Plastikman, Daniel Bell (as DBX) and Infiniti (aka Juan Atkins), while Hood and Jeff Mills unleashed a series of records that dominated the clubs. Hood’s ‘Internal Empire’, which included the classic track ‘Minus’, was an inspired follow up to ‘Minimal Nation’, stripping his sound even further back, while adding a certain pointed clarity to the mix. Mills’ ‘Cycle 30’ and (in particular) ‘Growth’ EPs were wild — the sound of minimalism with bloodied teeth and a nervous disorder.

Around the world, meanwhile, producers like Basic Channel, Surgeon, Regis and Mika Vainio were cooking up their own takes on the minimal sound, borrowing from industrial, dub and experimental noise. By 2007, minimal was, arguably, the biggest genre in all of dance music, its spartan strains heard on dancefloors from Ibiza to Berlin and beyond.

Success, of course, also brought dilution. The game-changing impact of 'Minimal Nation' was so powerful that it arguably caused a short circuit in the techno mainframe, unleashing a trail of imitators so persistent we will be dealing with them decades into the future. Hood remains phlegmatic — and incredibly tactful — when asked about his copycat trail.

“It was mixed emotions,” he says, after a lengthy pause. “I look at it from a hip-hop stand standpoint where people bite your style, borrowing from it. At the same time, it’s also flattering that you're influenced — or inspired, I should say — by something I made.”

“I didn't want people to mistake this as something easy to do,” he adds. “It's not necessarily an easy thing to do. You have to have a courageous spirit to say, ‘Let's strip everything down to just a drum machine and a bassline and a hi-hat. And still make it soulful and make you feel it’. I heard some artists, some DJs, producers, doing it. And, well, I think they're missing the point, some of them. Some of them did it very well. But for the most part, a lot of them missed the point.”

Not ‘Minimal Nation’ though. 30 years on and thousands of imitators later, this album still hits like a silver hammer to the heart, an injection of hard machine funk that screams with soul. “I think ‘Minimal Nation’ just hit at the right time,” Hood concludes. “With the stage being set, it made sense. And, like I said, if it's real and that groove is hidden in your soul, that's what it was made for: just to hit you right in the soul, right in the heart.”