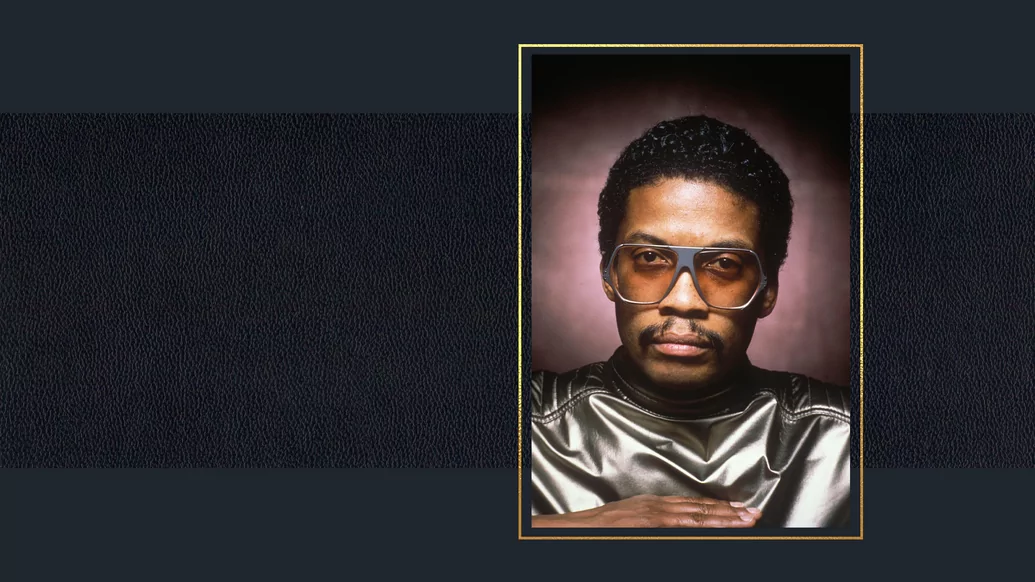

How Herbie Hancock's 'Future Shock' transcended genre and blazed a trail for hip-hop

Forty years ago, in August 1983, jazz keyboard legend Herbie Hancock released 'Future Shock', a genre-defying album that introduced audiences around the world to vinyl scratching, hip-hop beats and sampling. It ushered in a new era of production techniques and studio exploration, and laid a blueprint for the following decade's hip-hop explosion. Here, Marke Bieschke explores the record's incredible legacy

Forty years ago, in August 1983, jazz keyboard legend Herbie Hancock decided to step into the future, taking the music industry — and, incidentally, global culture — with him. That was the year his album ‘Future Shock’, with its earthquaking single ‘Rockit’, introduced much of the world to vinyl scratching, hip-hop beats, sampling, computer-enhanced effects, and what we today call electronic dance music. By mixing freestyle jazz experimentation with brash robotic grooves, the record laid a blueprint for the following decade's explosion of hip-hop – then considered a Grandmaster Flash-in-the-pan by major record companies. Despite jumpy corporate execs, the album’s massive, Grammy-winning success simultaneously ushered in a new era of production techniques and studio exploration.

When Hancock first played the album for the suits at his Columbia label, the sound of scratching left them scratching their heads. How could they possibly market such a weird record, which crossed so many genre lines? He had to push for it to be released at all. Technically though, ‘Future Shock’ wasn't such a leap for Hancock. At 43, he already had 34 albums under his belt (no small feat in the era before bedroom production), and had helped spark several musical revolutions. These included the small-combo post-bop and wild electric fusions made alongside his mentor Miles Davis, and the platinum-selling jazz-funk of his own crossover smash, ‘Headhunters’. Afrocentric references and downtown street sounds melded with avant-garde soul flights in his work, and his quest for new directions led to constant reinvention.

Nor was 'Future Shock' much of a geographic bounce from the New York jazz venues where Hancock constantly appeared, considering the explosion of hip-hop and underground dance music happening in the city at the time. Nonetheless, that era's corporate-decreed boundaries around what could and could not be mixed together, genre-wise, made ‘Future Shock’'s incorporation of hip-hop all the more astonishing.

Fortunately, ‘Future Shock’ arrived at a rare aperture in musical time, a portal out of category, when pop artists were beaming influences from every genre into radiant amalgams: see Michael Jackson's ‘Thriller’, Madonna's ‘Madonna’, Talking Heads' ‘Speaking in Tongues’, Malcolm McLaren's ‘Duck Rock’, Afrika Bambaataa & Soul Sonic Force's ‘Planet Rock’. State-of-the-art studio tools and new avenues of expression such as music videos, boomboxes and hip-hop block parties were just as important in forming these unique creations, and took them to wider audiences beyond traditional, genre-segregated radio stations. ‘Rockit’, especially, represented this fusion of gleaming technology and streetwise energy.

“‘Rockit' desegregated and de-ghettoized pop music, if only for a brief moment,” wrote the late jazz saxophonist Bob Belden in the liner notes of ‘Future Shock’'s 1999 reissue. “The composition reflected the mixing of an inclusive and collaborative urban culture, but was produced with such elegance that the sound of urbanism was embraced worldwide.”

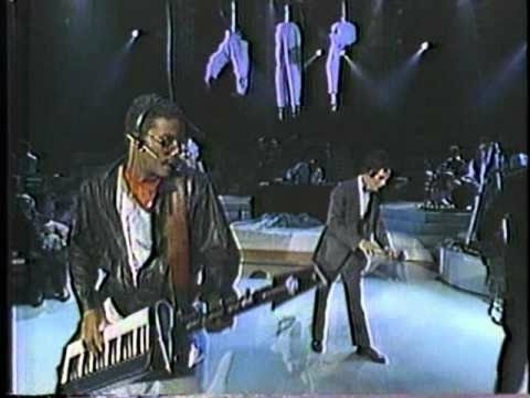

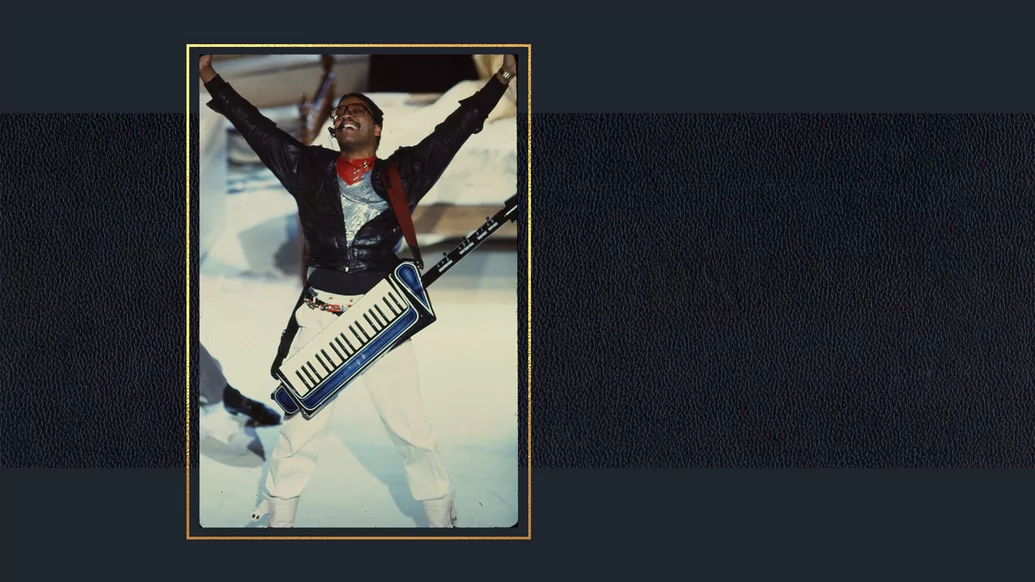

“The music video for 'Rockit' also broke vast new ground,” he continued. “MTV played it in heavy rotation, and Herbie was seen picture-in-picture, among the very first African-Americans to actually be seen and featured on the historically all-white MTV.”

Over the course of its six tracks, ‘Future Shock’ runs through jazzed-up electro-boogie, spaced-out funk, and buoyant post-disco jams. ‘Earth Beat’ summons koto-like twangs and non-Western textures without ever succumbing to the Orientalism then rampant in synth-pop. The propulsive bass, chiming proto-house piano, and squiggly ornamentation of ‘Autodrive’ fit right into the 12” mix expansionism that was then ruling dancefloors. The breakdance-ready ‘FTS’ and the future-soul of ‘Rough’ showed off the capabilities of recent electronic instruments like the Memorymoog, alphaSyntari, Fairlight III, Rhodes Chroma, and Oberheim DMX.

And then there's ‘Rockit’, with its monster groove, clarion keyboard riff, bass sampled from the jazz god Pharaoh Sanders, and an unheard-of use of the turntable itself as a melodic instrument. (Ironically, the title track, a chugging update of a decade-old Curtis Mayfield chestnut, is the only one on the album to sound past its due date.)

While the overall sounds of Future Shock were definitely emanating from Black New York, specifically the South Bronx where hip-hop was incubated, it took a multiracial, and transatlantic, game of musical telephone to dial in the album's signature sound. “Hancock in effect created a world music album, like Paul Simon’s ‘Graceland’,” says Mark Montgomery French, a music historian, lecturer, and host of the All Your Favorite Music Is (Probably) Black podcast. “But instead of leaving New York to go to South Africa, Hancock simply went to a different block.”

As Hancock himself told the Guardian in 2022, a young percussionist friend turned him on to UK provocateur Malcome McLaren's ‘Buffalo Gals’ in 1982. (McLaren himself had pinched the vinyl scratching technique for the track after he first heard it at a New York block party thrown by Afrika Bambaataa.) At around the time Hancock became enamoured with the sound, he met two cutting-edge musician-producers, Bill Laswell and Michael Beinhorn of the band Material, who were eager to work with him on his next reinvention. According to Hancock, "I said: 'I want to do something with scratching!' 'Rockit' was the first thing we worked on, and I decided: 'Let’s do the whole record with these new guys.'

Laswell and Beinhorn had already written much of the material that became ‘Future Shock’, including the rudimentary scratch track by one of the first turntable manipulators, Grand Mixer DXT of Manhattan (then known as D. St.) that became the major element of ‘Rockit’. Once the decision to feature the turntable as a lead instrument — and to construct the album mainly from electronically generated sounds — was made, the rest of the track fell into place. Laswell and Beinhorn even sampled one of their own songs with New York rapper Fab 5 Freddy, ‘Change the Beat’, to produce Rockit's iconic “Fresh” sample, which has gone on to become one of the most deployed samples in hip-hop. "'Rockit' became so big, it opened everything up," Hancock said. "Rap was just starting to happen, and then that whole scene blew up.”

“I didn't have any idea how other people might feel about it when we were making it,” Beinhorn said of ‘Rockit’ in an 2022 interview with Gear Space. “All I knew was, it didn't sound like anything else I'd heard, and I was excited every time I heard it or worked on it. In that case, I felt we had something special.”

While scratching has since fallen away as the signature sound of hip-hop, ‘Future Shock’'s legacy can still be heard in contemporary electro, trap, and even ambient productions, and in the work of artists as disparate as Fatima Al-Qadiri and Carl Craig. ‘Rockit’ still fills dancefloors, and its Godley and Creme-directed video, a phantasmagoric vision of dismembered mannequin parts hooked up to glitching machinery, remains one of the early landmarks of the art.

The concept of “future shock”, taken from the title of a bestselling 1970 book by philosopher Alvin Toeffler — that too much technological change, too fast can cause overwhelming psychological trauma — remains alarmingly relevant. The ‘Future Shock’ album helped usher in an electronic paradigm, which transformed the world in ways we're still trying to wrap our heads around. But perhaps the work itself will be remembered most for its astonishing transcendence of genres and backgrounds, slipping through that rare window in history.

“Black and white musicians have always listened to each other’s output and would have collaborated more often, if not for label interference,” says Montgomery French. “For every 'Donna Summer co-writing dance tracks with Giorgio Moroder', there are many more 'Chaka Khan’s vocals get removed from Robert Palmer’s ‘Addicted to Love''. So props to Columbia Records for releasing a significantly bugged-out album. It gets weird when musicians lock themselves into different classes and refuse to acknowledge another genre’s talent. Classical musicians historically have looked down on jazz musicians. Jazz musicians looked down on saxophonist Branford Marsalis when he played with Sting, and that was only two years after 'Rockit'!

“But I saw Herbie Hancock live at this time, and he treated Grand Mixer DXT with the same artistic and instrumental reverence as any other musician in his band,” he continues. “It was the first time I witnessed a jazz musician give that much respect to a scratch DJ.”

That the classic and the street could meet each other on such equal ground is just one of the legacies of ‘Future Shock’ and its audacious breakthrough.