Louie Vega: ride on the rhythm

After four-plus decades of DJing and with a incredible list of releases — much of it produced with longtime partner Kenny “Dope” Gonzalez as Masters At Work — the pioneering Louie Vega would seem to have little to prove. Yet he’s working harder than ever, with the same energy he had as a young kid coming up in the Bronx. In the run-up to his date at DJ Mag’s Miami Pool Party 2024 at the Sagamore Hotel on March 20th, Vega took some time out of his hectic schedule to talk about how he got to where he is today

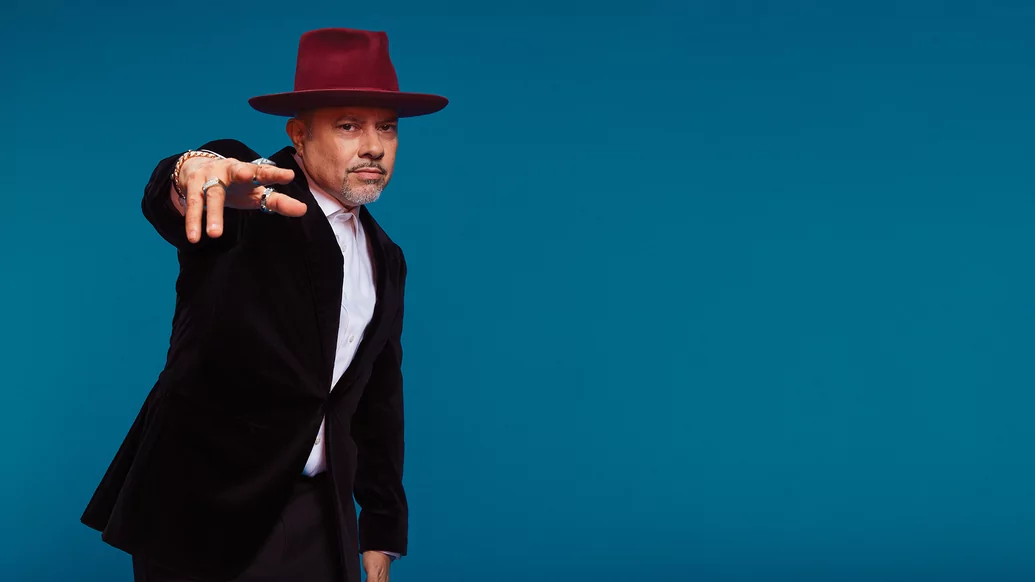

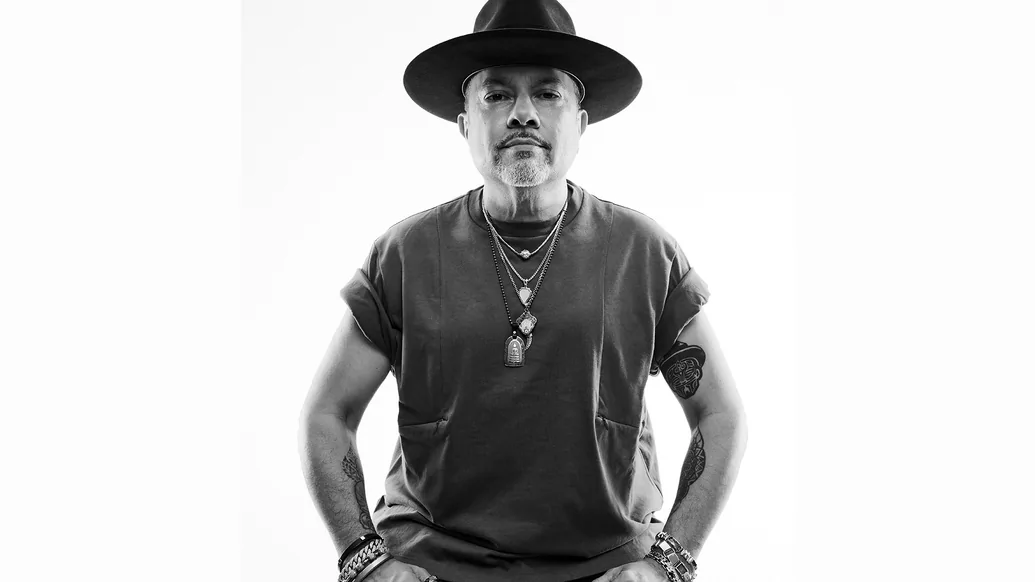

Sitting in his Manhattan studio on a weekend evening, wide-brimmed hat on his head and, behind him, shelves crammed with thousands of records — most of which he likely had a role in making — Louie Vega appears to be both relaxed and full of energy. He should be neither. Just a few nights before, he’d finished up with a series of live performances with his Elements Of Life combo, at London’s HERE at Outernet venue and the storied NYC jazz club the Blue Note. After a busy week in the studio following that, he’s about to embark on a series of back-to-back sets with his wife Anané Vega as part of their long-running party series, The Ritual. Yet here he is, as amiable and animated as ever.

“Yeah, it’s a whirlwind,” he admits, about as close as Vega will ever come to even hinting at burn-out. “And I don’t have much time to rest before I go into the next thing.” Vega’s conception of “rest”, though, is probably far different than that of the average person. Since his start as a teenage DJ in the ’80s, he’s been possessed — not by demons, even though he once had a residency at a club called the Devil’s Nest, but by music. He’s seemingly never taken a break, and from the looks of what he has in the pipeline, things won’t be slowing down anytime soon.

“Let’s see,” he says, pausing for a few beats to pull the strands of his upcoming schedule together. “Oh, I’m working with [jazz–hip-hop fusionist] José James. Do you know him? He’s so good. The song is called ‘Saturday Night’ — you’ll hear it. I have a Leroy Burgess record coming out on Vega Records; there’s a new Elements Of Life coming called ‘Dusk On The Beach’; there’s possibly a Tony Touch record coming. There are so many remixes on the way — Tedd Patterson, Dimitri From Paris, Jazzy Jeff, and I think some others. And I have a bunch of tunes I did with the Martinez Brothers. We’re talking about doing an EP.”

“When I was 11 or 12 years old, we used to go to the jams. Afrika Bambaataa, Jazzy Jay, Red Alert, Afrika Islam, breakdancing — it was all happening, pre–hip-hop. It was incredible, listening to all the different types of music.”

He hasn’t even gotten to the long-standing, game-changing collaboration that first brought Vega to superstar-level fame beyond the confines of his native New York — his work with Kenny “Dope” Gonzalez as Masters At Work and its Latin-and-jazz-oriented offshoot Nuyorican Soul. Since the pandemic, the pair have been digging through the vaults (“750 two-inch tapes, temperature-controlled, professionally stored for over 26 years,” Vega says) for the monthly ‘MAW Lost Tapes’ series, with many of the tracks rivaling the pure house power of the duo’s best releases. The monthly series has just hit its 13th installment — but of even more consequence, there’s the news that partnership is more active than ever, with new material on the way.

“We’ve been working on a new Nuyorican Soul,” he casually announces. “We already did about nine tracks, and it’s feeling really good. At the same time, we're doing a Masters At Work album. So you have Nuyorican Soul with that sound, and you have Masters At Work with the more club-oriented sound, and then you have more ‘Lost Tapes’. But before those two albums, we need to complete this album that we were just hired to do for Brian Jackson, who was Gil Scott-Heron’s musical partner. That record’s going to have a lot of amazing artists on it — imagine Brian Jackson meets Nuyorican Soul!”

He hasn’t even mentioned Two Soul Fusion, his ongoing collaboration with Josh Milan of the trailblazing New Jersey house unit Blaze — Vega and Milan also coproduced Anané’s recent solo EP ‘Take A Ride’ — or his constant flow of DJ sets, or probably a dozen other things. How does he... “Balance it?” he asks, completing the question. “Well, I’m working all the time. But I make sure everything has its time — I just make sure I don’t pile everything together.” Still, that’s the kind of schedule that would tear a normal human to pieces — but Vega’s musical itinerary has been full for years, ever since he was a kid growing up in the Bronx.

Vega grew up on Stratford Avenue, just up the block from the Bronx River projects in the Soundview neighborhood, surrounded by music. “My father played the tenor sax. He was in Latin bands for many, many years, and he also loved jazz — Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Charlie Parker were always blasting in the house, and he would play sax on top of the music. And my mother, her younger brother was [famed salsa vocalist and bandleader] Héctor Lavoe. He would come in and play a seven-inch test pressing of his new record, and then six months later it would be the biggest hit. And then you had my sisters, who were in high school — one worked as an apprentice in a hair shop, and the boss would take all the young girls with him to go to the clubs in the city, like the Sanctuary and the Loft. She and her friends would make cassette tapes of the songs they would hear, all these underground records that I didn’t hear on WABC, like disco but a kind of fusion — records that are considered classics today. All these different elements became a big part of my foundation.”

Starting at age six, Vega’s father enrolled him in piano lessons; he also studied violin for a year and was a member of his school’s glee club. This was the ’70s, tough times in much of the South Bronx, but it was also a vibrant cultural time, particularly when it came to the music that was blowing through the Bronx streets — which is where Vega absorbed another kind of musical knowledge, of a sort they weren’t teaching in music lessons or glee club.

“When I was 11 or 12 years old, we used to go to the jams,” he recalls. “Afrika Bambaataa, Jazzy Jay, Red Alert, Afrika Islam, breakdancing — it was all happening, pre–hip-hop. It was incredible, listening to all the different types of music. It was a lot of breakbeats — from rock records, from jazz records, from soul, from funk, from disco, even early punk rock — it was just the sound of our streets. We all loved it. But as a kid, I didn’t think that this was a new movement. It was just like, ‘This is the music I’m listening to in my neighbourhood.’”

Soaking the music in, and seeing the power that the DJs had, it’s hardly surprising that Vega would want to give it a go himself. As luck would have it, a friend’s older brother had some basic gear — “I think it was a GLI 9000 mixer, and he had Technics turntables, but they were the belt-drive ones” — that enabled him to get a taste. It was then that his nascent hustling proclivity began to show itself. One of his neighbors was a mobile DJ, spinning disco at weddings and sweet-16 parties. The young Vega scored himself a gig as his apprentice, lugging the gear and crates of records to the events.

“Eventually I said, ‘Well, I’ll do the apprentice thing, but in return loan me the equipment — two turntables, the mixer, the set of speakers and two crates of music of my choice.’ He said, ‘No problem.’ And that’s how I started getting into mixing.” Soon, he was on the decks on a regular basis. His sisters would toss jams that Vega would DJ for; a friend was a DJ and promoter who would secure gigs at the local YMCA; he would spin local high-school parties. Tickets were sold out of his older sister’s hair shop. Vega was also an avid roller skater — “like hardcore, not just rolling around the rink but actually dance skating” — which led to his first experience, in 1981, of playing in something resembling a real-deal club environment.

“There was a roller-skating rink that was in my neighborhood called Roller World. It had the biggest disco ball you’ve ever seen and the lighting was beautiful. The DJ there knew that I liked to DJ. He said, ‘Louie, I gotta go to the bathroom. Do me a favor, just cue records,’ and he didn’t come back till like 45 minutes later — meanwhile, I was playing to a floor full of roller skaters. It was crazy! I specifically remember I was playing Denroy Morgan, ‘I'll Do Anything For You’.”

“I wanted the music to feel like the music at those places, so I modelled my sound from the mixing of Tony Humphries at Zanzibar, the cutting of Bruce Forest at Better Days, the way that Larry would tweak the songs at the Garage, and Jellybean at the Funhouse.”

Another turning point came in 1980, at the club that played the same role in the careers of scores of other NYC-area DJs — the Paradise Garage. Vega was only 15, but his neighbour Lenny was a member, and one of his sisters had a cousin who worked security, so entry was no problem. (Not that being underage was much of a problem in NYC’s clubland at that point anyway.)

“I will never forget when I walked in,” he says. “I heard [Chicago’s] ‘Street Player’, I heard [Taana Gardner’s] ‘When You Touch Me’, I heard [Candido’s] ‘Thousand Finger Man’, I heard [Dee Dee Bridgewater’s] ‘Bad For Me’... goodness, there were so many. When I left that place I was like, ‘Wow, that is mind-blowing.’ Seeing Larry Levan at his prime, doing his thing up there and watching the crowd go crazy, hearing that sound system and the way he tweaked the records... he was using acapellas and sound effects, and the way he brought in records just at the right time, it made me think, ‘You know what, I want to go to more of these clubs. I need to hear more DJs.’ The early ’80s were a golden era in NYC’s clubbing history, and Vega began gathering up knowledge at such iconic clubs as Newark’s Zanzibar, Better Days in Hell’s Kitchen, and the Funhouse on West 26th Street.

“I wanted the music to feel like the music at those places, so I modeled my sound from the mixing of Tony Humphries at Zanzibar, the cutting of Bruce Forest at Better Days, the way that Larry would tweak the songs at the Garage, and Jellybean at the Funhouse. When you heard Jellybean, it was that early-’80s electro sound — Arthur Baker, John Robie, Kraftwerk, New Order, all of that — when it was still in its underground stages. Then with Larry, he had another level of musicality, it was just a whole other thing. David Mancuso at the Loft had his own style. Kenny Carpenter was another one.”

By the mid-’80s, he was ready to start writing his own name on that list. In late 1984, Vega got his hands on a 600-capacity club in the Bronx called Chez Sensual, which somehow boasted a sound system by Richard Long, the audio genius responsible for the system at the Garage. The first two nights were rammed, and for the third night, he decided they should host a performance. These were the formative days of freestyle, and one of the earliest of the genre’s hits was Nayobe’s ‘Please Don’t Go’, first released in late 1984 on Fever Records. Vega scooped her up to perform at the club. “Nayobe blew it away,” he recalls. “It was amazing. I met Andy Panda, who was a songwriter and producer of that song, and I met Sal Abbatiello, who owned Fever Records. They saw what I was doing at that club, and they couldn’t believe it — like, ‘Look at all these kids having a good time.’”

Abbatiello’s father had his own venue, a salsa club in the South Bronx, and Abbatiello had been casting about for a new direction for the spot, a large basement room that had once been a bowling alley. “And he said, ‘This is what I want to bring to this club, this is perfect,’ and he ended up hiring me,” Vega says. “He asked me to come in and play on a Friday night, and those kids came — boom, the club was packed.”

The club was the Devil’s Nest, and Vega ended up playing both Friday and Saturday nights for the next 10 months. It was his first real club residency, and it saw him playing a major role in turning tracks from the likes of the Cover Girls, Exposé and Stevie B into hits, both in clubland and on the radio. Soon, Vega himself was involved in studio work. “Arthur Baker would invite me to his studio, or Jellybean would invite me into his studio,” he says. “It would be like, ‘Louie, just sit and check out what’s going on. Any questions? Just ask.’ I took advantage of all those moments. With Jellybean, we became good friends and he kind of became a manager at that time.”

Soon, Vega was hard at work helping to refine the freestyle / Latin hip-hop sound further, often working with the acclaimed editing team the Latin Rascals. The first two tracks that had the “Little” Louie Vega name on the label were a remix of Information Society’s ‘Running’ and a dub of Cover Girls’ ‘Show Me’, both released in 1986. (Vega ditched the “Little” sobriquet years ago.) Other early mixes included Noel’s ‘Silent Morning’, Debbie Gibson’s ‘Out Of The Blue’ and Erasure’s ‘Victim Of Love’. “I made about 80 of those records between around ’86 and ’89,” he estimates.

That Cover Girls version was named ‘Hearthrob Mix’, its moniker taken from the club where Vega landed after the Devil’s Nest. (It was a full circle for Vega, as Hearthrob had taken over the West 26th Street spot that had previously been home to the Funhouse.) These were the days when DJs, even known entities like Vega, often had to audition for gigs — and it probably didn’t hurt his chances that he strolled into his tryout accompanied by Jellybean.

“When I started, the Bronx crowd started coming in, and Queens and Brooklyn too — really everybody started coming in,” Vega says. “It would be packed, up to 4,000 people at that club. It was crazy.” Vega ended up staying at Hearthrob for two years, while plying his trade as a guest at clubs like Octagon and 1018. He finally left Hearthrob to take on a residency at Studio 54, in one of that famed venue’s final incarnations as a club, followed by a stint at the massive Roseland Ballroom on West 52nd Street. By that time, freestyle had started to fade as a major force in the New York clubs. “I was playing hip-hop,” he says, “I was playing reggae music, I was playing disco classics, and the breakbeats from back in the projects — and by then, I was playing a lot of house music.”

In 1989, Vega began working with his friend Todd Terry. “Todd liked the way I was mixing records,” Vega says, “and he was like, ‘Louie, I’m doing so much music. I don’t have time to mix them. Why don’t you mix them for me?’ If you look at this period, I did a lot of Todd Terry’s projects, like Black Riot’s ‘Just Make That Move’, Sax’s ‘Give Yourself To Me’, D.M.S.’s ‘And The Beat Goes On’.” He had also begun to compose his own house tunes, tracks like 1990’s ‘Feel The Magic’, released on Warlock Records and credited to Soul Fusion. It was around this time that a collaboration began that would not only play a defining role in Vega’s career, but in the trajectory of house itself.

“Everything just kept coming in and we were on a roll, working 16 to 18 hours a day. But we were so excited about making music and the adrenaline was there. It was just two, three records in one day, every day. It was hardcore.”

“Kenny had heard about me through the scene,” Vega says, referring (of course) to Kenny Gonzales. “He had this record, ‘A Touch Of Salsa’ [released in 1990, and credited to 2 Dope] that sampled Celia Cruz and Sylvester. I heard him play it and I was like, ‘Wow, this record is dope. Todd, you know this guy?’ And Todd goes, ‘Yeah, Kenny, he's a friend of mine from Brooklyn. He works in a record store called Record Center.’ I said, ‘Oh, you should introduce me to him. And I would love to do a remix on this record.’ He introduced me to Kenny, but I never ended up remixing the record, because by that time in 1990, I was offered my first album project.”

Marc Anthony, at the time, was a young singer and songwriter on the rise who had a side trade in vocal coaching for freestyle artists — Vega recruited him for the album, which came out in 1991 as “Little” Louie & Marc Anthony’s ‘When The Night Is Over’. “I had told Kenny, ‘I love the way you make beats. Why don’t you make some beats for this album?’ And he ended up doing all the beats to the whole thing,” Vega recalls. “We would get together in a studio that was full of synths and drum machines, and I would say, ‘You just make a beat and let me play to it.’ And that’s when the Masters At Work sound was born.”

Offers of work were soon pouring in — thanks in part to the label connections that Vega had made over the years — resulting in now- classic Masters At Work versions like Debbie Gibson’s ‘One Step Ahead’, Saint Etienne’s ‘Only Love Can Break Your Heart’, Vega and Marc Anthony’s own ‘Ride On The Rhythm’, Tito Puente’s ‘Ran Kan Kan’, Chic’s ‘Chic Mystique’, Neneh Cherry’s ‘Buddy X’, Madonna’s ‘Erotica’, and hundreds more. “Everything just kept coming in and we were on a roll, working 16 to 18 hours a day,” he says. “But we were so excited about making music and the adrenaline was there. It was just two, three records in one day, every day. It was hardcore.”

Yet for all that churn, the quality, whether on their remixes or their original productions, rarely wavered — and whenever a new Masters At Work record appeared on the wall of the local shop, they’d soon disappear into the crates of right-thinking DJs. “For us, it was all about always coming up with different sounds,” Vega says. “Kenny would have all these different drum kits for all the remixes, and I’d always change up the sounds — different bass sounds, different synth sounds. We were always buying new synths, and we were always like, ‘Oh my god, check out the sounds!’”

One of the newest sounds of all came in 1993, via a record that felt like nothing that Vega and Gonzalez, or few others, had produced before — ‘The Nervous Track’. As he can with pretty much any music he’s played a part in, Vega happily goes into detail about the track’s production. “When it came to ‘The Nervous Track’,” Vega relates, “Kenny was like, ‘I’m tired of doing house beats, Louie!’ I said, ‘Alright, just try a different beat and let’s see what happens.’ So he sampled these jazz drummers, four drummers on top of each other. He cleverly sampled different loops of these snare patterns, small loops, and he put them together to create that groove. And then he put these kicks on there that were syncopated, they weren’t four-on-the-floor. It sounded incredible. “Then I played the bass, these long notes, with a sound that was kind of cool,” he continues.

“I believe we were inspired by [Jaydee’s] ‘Plastic Dreams’, which is why I put that ‘doo do-do-do doo’ in there. And then you hear ‘doo-doo doo doo’ answering that, which is the bass playing a higher octave. It was such a cool little vibe. And there’s those chords, those eerie chords, from an Oberheim Matrix, and the chords develop the mood of the record. And when we did those three chords, we said, ‘Okay, this sounds really good.’ Our friend Tony [aka Anthony “Starvin T” Cordero] played live percussion on it, and we asked Paul Shapiro, who you may know from his work with Frankie Knuckles on ‘The Whistle Song’, to play on it as well.”

At the time, Strictly Rhythm and Nervous Records were the two big dance labels in town, vying for the next major club tune. In the case of ‘The Nervous Track’, it was Nervous that came out ahead. “They called me about four o’clock in the morning,” Nervous boss man Michael Weiss recalls, “and I said, ‘Can you play it over the phone?’ And they said, ‘No, you’ve got to come to the studio.’ So I woke up and ran down there. It didn’t sound like anything else — with the crazy beats and Louie with those special chords. They said, ‘Okay, we’ll lay down the tapes. Come back in the morning, we’ll leave it for you in the front.’ And then when I got there in the morning, there it was, with a sticker that said ‘nervous track’. And I thought, ‘that’s it, that’s got to be the name.’”

Vega and Gonzalez were considering expanding Nuyorican Soul into a larger project — and before long, as luck would have it, the UK DJ and tastemaker Gilles Peterson had commissioned a full-length Nuyorican Soul album for his Talkin’ Loud label. The pair reached out to name-brand artists they’d already worked with over the years — Jocelyn Brown, India [aka Linda Viera Caballero, Vega’s wife from 1989 to 1996], Tito Puente, Eddie Palmieri and Roy Ayers. “And then we had a chance to get connected with George Benson,” Vega says. “We had the meeting with George — and he was like, ‘Let’s do it!’ And we did it!” The result, succinctly titled ‘Nuyorican Soul’, was a 1996 stunner, slickly produced and rich in scope, taking in strands of jazz, Latin music, R&B, and more. It was a sign of not only Vega’s (and Gonzalez’s) willingness to stray far beyond the house template, but also of Vega’s talent in working with large ensembles, something that would serve him well in coming years.

“We would do things that would blow people away. Like one night, we did ‘Love & Happiness’ and Tito Puente came after he played at the Blue Note to play it with India. We also asked George Benson to come, and he loved this so much that he got on stage and sang ‘Give Me The Night’.”

Vega had put DJing on hold at the beginning of the ’90s, but in 1992, he returned to the decks with a vengeance via the Wednesday-night Underground Network parties at Sound Factory Bar at 12 West 21st Street, where none other than Frankie Knuckles was holding it down on Fridays. Produced by longtime nightlife figure Don Welch and co-promoted by a young Barbara Tucker — with whom Vega would soon be working on such beloved tunes as ‘Deep Inside’, credited to Hardrive, and ‘Beautiful People’ — the party served as an HQ for the city’s and the world’s house scene. “We would do things that would blow people away. Like one night, we did ‘Love & Happiness’ and Tito Puente came after he played at the Blue Note to play it with India. We also asked George Benson to come, and he loved this so much that he got on stage and sang ‘Give Me The Night’.”

A 1999 studio session with Blaze’s Josh Milan and Kevin Hedge brought about yet another project, one that would provide much of the focus of Louie’s musical life for the next two-plus decades. “We got together in the studio,” Vega says, “and they pull out this little notebook and said, ‘I think we got something for you.’ It said ‘Elements Of Life’ — it was this beautiful poem. The words were beautiful. Josh sang the demo, and I loved it so much that I didn’t want to get anybody else to sing it.” He called in vocalist Cindy Mizelle to sing background vocals. “And then Josh played the piano solo, and that was it — I already had the track.”

The resulting tune, simply called ‘Elements Of Life’, was a swirling, musically rich gem, with vocals gliding over a gentle Afro-Latin rhythm, and came out the following year; an album, credited to Vega with ‘Elements Of Life’ serving as the album title, followed in 2003. Deep and soulful house fans took the music to heart, but Vega, his appetite for live ensembles whetted by his Nuyorican Soul experience, wanted to push it further — he wanted to bring the album to life with a performing ensemble. He started with Milan, Raul Midón (a notable vocalist and musician active in the Miami scene) and Anané.

“We had been together five or six years — we were already married,” Vega says of Anané. “And she told me, ‘You know, when I was young, I was in a singing group, and I write.’ I was like, ‘What? You never told me?’” She ended up penning several of the LP’s cuts, including the bossa-flavored songs ‘Nos Vida’ and ‘Ma Mi Mama’, about their new son, Nico. That baby’s voice you can hear in the latter tune is him. Now 23 years old, Nico’s something of a studio savant himself — “He’s pretty savvy on Ableton,” his father proudly says — and during Covid, when Vega’s usual engineer couldn’t come to the studio, Nico stepped in for a series of productions and remixes. “Like when we did ‘Downtown’, the Honey Dijon record,” Vega says. “Nico programmed it and mixed it. It was amazing.”

There were more Elements Of Life albums to come — the ‘Louie Vega Presents Elements Of Life: Eclipse’ album hit the shops in 2013 — but years earlier, Vega, Anané and the burgeoning combo played a show that would be seen by 80,000 in person and another 145 million (give or take a few million) on TV — the 2007 Super Bowl pre-game show. “What a surreal experience,” Vega says, still seemingly awed. “We were on right after Billy Joel sang the national anthem. Imagine! And then guess who was the halftime performer — Prince!”

If you watch the video of that performance, or of the recent shows in London and at the Blue Note, you’ll see Vega front and center, conducting the musicians in much the same way that he saw his uncle, Héctor Lavoe, lead his band years earlier. “At first, I wasn’t even meant to be on stage with the band,” he says. “I had grabbed all my session musicians, some of them who I had already been working with for 13 or 14 years, and showed them all about the transitions and this and that, and I told them, ‘Listen, when you guys get on stage, it’s got to be tight.’ And they were like, ‘Wait a minute, you’re not going to be on stage with us?’ It was [bassist] Gene Perez who convinced me. He’s like, ‘Louie, I think your fans would love for you to be on stage, directing us. They would love to hear you talking to them, telling your stories.’ I mean, it’s not that I want to be in the front, but I look at the playbacks, and it’s like, ‘Wow, it really looks natural,’ just like in the way the band responds to my signals, and how I’m saying things to them. It’s turning into a James Brown thing.”

A few days after the interview, it’s time for Vega’s photo shoot. Though he’s barely left the studio since then, he's buzzing when he arrives at the Brooklyn studio with Anané, who’s serving as his stylist for the day. “Oh man,” he says, “so much has been happening. I’ll send you an email!” Sure enough, that evening, a message from Vega appears. Written in a stream-of-consciousness flow of joy — the subject is the Brian Jackson album that he and Gonzalez are producing — his excitement jumps from the screen.

“We have been recording artists and musicians b2b, it’s been a nonstop love train up in the studio recording the icon Brian Jackson on Fender Rhodes, piano, synths, background vocals, and lead vocals,” it reads in part. It goes on to mention the other artists taking part in the recording, a dream team of musicians including Luisito Quintero on percussion, Sherrod Barnes and Binky Brice on guitar, Gene Perez on electric bass, and Lisa Fischer, Cindy Mizelle, Raheem DeVaughn, Rich Medina, Moodymann, Josh Milan and Rahsaan Patterson on vocals, among others. “And there are some more huge surprises in store!”

It’s been over four decades since he began spinning as a teen, but Vega obviously isn’t going anywhere — not with the enthusiasm with which he still approaches his work, and certainly not when he and his music are still connecting with the next generation. He name-checks younger Brooklyn artists like Cesar Toribio — in 2021, he laid down a series of mixes of ‘Perdón’, from Toribio’s Conclave project on Love Injection Records — and the musclecars duo. “There’s so much talent coming out of Brooklyn right now, and it’s nice to create a little bridge with all these artists,” Vega says. “I actually just did a remix for musclecars that came out incredible. They haven’t even heard it yet!” The man, it seems, never stops — and he probably never will.