Orbital: on and on

Orbital’s 10th album, ‘Optical Delusion’, explores division, discontent and dislocation, but equally celebrates collective rave euphoria. Joe Roberts speaks to the Hartnoll brothers about writing the record in lockdown, the enduring live evolution of 'Chime', co-opting pop, and more

“When’s the zombie apocalypse coming?” jokes Paul Hartnoll, one half of Orbital, as we’re chatting over Zoom about the run of events leading up to the release of the band’s 10th album, ‘Optical Delusion’. A celebration-worthy milestone for any group, it follows hot on the heels of 2022’s ‘30 Something’, a compilation that celebrated over three decades of music making with reworkings and remixes of iconic tracks such as ‘Halcyon’ and ‘Chime’. It was also a year that saw the release of their soundtrack to ‘The Pentaverate’, a Netflix series created by Mike Myers. Yet ‘Optical Delusion’ is no victory lap. Instead, it’s an album that comes out swinging.

Debut single ‘Dirty Rat’, a collaboration with Sleaford Mods, is a growling, incendiary blast of heartfelt anger towards the state of our nation. Unflinchingly referencing drowned migrants as it alludes to Tory-voting gammon, it’s filled with rage. Second single ‘Ringa Ringa (The Old Pandemic Folk Song)’ pivots, recalling the dreamy, swirling, trancey melodies of Orbital of yore. But its Mediaeval Baebes-sampled vocal of the nursery rhyme ‘Ring A Ring O’ Roses’, whose lyrics recall 1665’s Great Plague of London, draws you to the on-going global pandemic — something news cycles had squeezed to the margins until recently.

Recorded during lockdown, ‘Optical Delusion’ doesn’t shy away from division and discontent, track titles such as ‘The New Abnormal’ and ‘Requiem For The Pre Apocalypse’ alluding to our precarious global state. This is, after all, the duo who wrote 1992 eco-rave anthem ‘Impact (The Earth Is Burning)’, retitling last year’s reversion ‘Impact (30 Years Later And The Earth Is Still Burning Mix)’, and made their debut appearance on Top Of The Pops in anti-Poll Tax T-shirts. But as well as addressing broader issues, the album speaks volumes about how Covid affected the Hartnolls themselves.

“As someone who hasn’t stopped since the early ’90s, it was quite nice — aside from all the caveats about people dying and the terror of the apocalypse,” says Paul, at 54 the younger of Orbital’s brotherly pairing. Beaming to us bright-eyed from his Brighton home studio, he decamped there during lockdown after collecting his favourite gear from the other larger shared complex he also uses. It was a period when he finally began to appreciate living in Brighton, having previously held onto a longing for the excitement of London.

“The seafront sort of became my home office, it was the social point of lockdown,” he says of morning walks to get coffee in the fresh sea breeze, people chatting while standing the regulatory two metres apart. Getting into running and Yoga With Adriene, he went “from FOMO to JOMO. I absolutely embraced the joy of missing out.” The studio became his sanctuary; in the early days of lockdown, Paul just wanted to make “group hug kind of music” like ‘The Crane’, one of three bonus tracks that come with the album.

It’s a period that seems distant now, the end of lockdown seamlessly sliding into a renewed threat of nuclear war after Russia invaded Ukraine. But it’s preserved in ‘The Virus Diaries’, an album Paul released in 2021 with poet and performance artist Murray Lachlan Young. Recording a track a week while Murray had a residency on BBC 6Music, titles such as

‘I Need A Haircut’ and ‘Working From Home’ bring back sensory memories even before Paul injects his modulating melodic moods into the dextrous verbal sketches. “It was really cathartic,” he recalls, praising Murray’s humanising touch and ability to move from the wry to the melancholic. “He said, ‘I want to talk about the human, micro side of it, rather than all the stuff we hear on the news.” It’s an intentional time-capsule, he adds, meant for listening back to in 20 years' time.

There’s a sense that among this newfound space and time, Paul was able to reassess his relationship to making music. The album’s second track ‘Day One’, featuring the vocals of Dina Ipavic, has a touch of classic ’90s Orbital, swelling epically with emotion.

Was it the result of revisiting their earlier tracks for ‘30 Something’, we ask? “I’d love to spin you a yarn about why it came about, but it was just one of those tracks from that period. It just came out as a bit of fun,” he says, adding that there was “a pure unadulterated joy of just doing something a little bit leaner”. ‘Ringa Ringa’ came from a similar playfulness, drawing a line between Covid and past plagues “via the medium of silly rave, something that everybody used to embrace back in the late ’80s and the early ’90s. I’m just going to grab something that feels fun and put it over a dance beat. It felt really cathartic to do that and quite old-fashioned, like anything goes, which is how dance music used to be.” But there was a juxtaposition too, he says, humanising the past and opening a door to the suffering of those who lived and died before us.

As lockdown ended, however, the feeling of gentleness began to subside. “It was like, ‘What the fuck is going on?’” he says, as the air of solidarity dissolved in contact with reality. The Sleaford Mods collaboration began with the Nottingham duo sending over vocal and musical parts that Paul began to assemble. “A Nottingham accent and a vocoder,” he says on processing Jason’s voice, “that’s got to be weird. It was, and I loved it!” The result, he says, has hints of “Front 242 and all that kind of industrial funk from the north of England from the ’80s”, as well as fitting into the lineage of protest songs that he grew up with.

“It’s what music always was when I was a teenager,” states Paul. Too young for the first wave of punk, instead he progressed from 2-Tone into the post-punk of bands such as Dead Kennedys, Flux Of Pink Indians and Crass, whose overt political message punctured the stuffy air of Dunton, the village he grew up in near Sevenoaks in Kent. “Albums like ‘Penis Envy’ by Crass, this overtly feminist album, put concepts in my head that I just wasn’t getting from home life.”

The bite of ‘Dirty Rat’ arrives with impeccable timing, various Tory MPs leaving what they see as a sinking ship. And with both duo’s ears for a hook ensuring it’s been listed on 6Music, it seems to have ticked something off Paul’s bucket list. “I know Iggy Pop played it. I mean, that just really tickles my fancy. He just talked about my band and said ‘Orbital’ in his lovely, croaky voice.”

It was 6Music where Paul’s wife, a potter, first heard Anne B. Savage, who appears on the track ‘Home’, going on to recommend her to Paul. “She’s almost like a modern day Scott Walker,” he enthuses, praising how “she sings about the dark corners of life that you don’t get into or think about”. Coming down to write in his studio, the pair had already clicked on the ride from the station over an unlikely shared obsession with town planning and new towns, utopian visions that often failed spectacularly. They even share the same favourite ’80s BBC documentary, filmed while Milton Keynes was still being built. This bonding informed the writing process, Savage coming off like a modern day Anne Clark as she recounts a city abandoned to nature, her plaintive chorus underlining the growing dislocation of our times.

‘Chime’, to anyone else, is a track that was recorded 30-odd years ago. It’s frozen in time. To me, it’s something that’s an ongoing, moving, creative piece. Every time I play it, I change it.” - Paul Hartnoll

It’s a dislocation reflected in Orbital. When we ask about another guest on the album, Paul tells us that’s one of Phil’s tracks. What does he mean? “I tend to be the writer of the tracks. Phil, he’s always come along and joined in and on certain tracks he’s written bits,” he says, citing the lead line on ’91 single ‘Choice’ as an example. “But he was jamming over what I’d done.” Some tracks in the past, he says, he’s written on his own, so the separation doesn’t sound totally unprecedented. “We had every intention of getting together at some point. But Phil didn’t really want to write music during the whole lockdown, so I ended up just finishing the tracks on my own. Then towards the end, Phil managed to get four tracks together from the little bits that he’d done. But I didn’t have any influence on them at all.”

A week later we arrange to speak to Phil. With his now familiar handlebar moustache, he’s four years Paul’s senior and often ends his sentences with a gruff laugh. But there’s an air of deadly seriousness when we ask about his experience of lockdown. “It was horrible,” he says. “I was shielding because I’ve got really bad lungs.” It wasn’t the only way his experience diverged from his brother’s. “Bouncing off the walls,” as he describes it, and unable even to listen to music, he realised that he probably has ADHD — although as yet hasn’t got an official diagnosis.

It was something, we say, various people we know also began to suspect during lockdown. For Phil, it retroactively explained the creative friction sometimes at the heart of Orbital, him sitting next to Paul in the studio “like the Tasmanian devil... I’d come in and go, ‘What about a breakbeat? What about doing this?’” It’s not the only close relationship in which it seemed to make sense. “I can see why my wife also gets irritated.” Having tried Adderall in America before: “Whomp! It just makes me focus.”

While Paul was able to lose himself in the studio enjoying his JOMO, Phil realised how much his mental well-being and creativity revolve around social interaction. “Paul’s almost obsessively in the studio every single day like a workhorse. I need other people,” he says. “I love bouncing off other people, that’s why I was in a band in the first place.”

Unfortunately, when lockdown ended there was even worse news, first his wife, then Phil himself going through cancer scares. “Music has sort of taken a back seat,” he says understandably, adding he’s finally given up a life-long addiction to smoking following a fatalistic period carrying on because he thought he was going to die anyway.

It sounds like a grim time, but out of it he was still able to contribute four tracks to the new Orbital album. ‘Frequency’ and ‘What A Surprise’ are glitchy, crunchy breakbeat tracks featuring The Little Pest, a mysterious guest whose identity is revealed, before Phil asks us to scrub it from the record. The others are with Japanese singer, songwriter and pianist Coppé, a cult figure who has been releasing jazz-influenced music since 1995, collaborating with the likes of Plaid, AtomTM, Daedelus, DJ Vadim and Q-Bert along the way.

“She thinks she’s a jellyfish from outer space,” grins Phil, “she’s the most amazing character.” Put in touch by Japanese friends, ‘Lost In Time’, which appears as a bonus track, began as a remix of a solo piano piece by Coppé. It was inspired by lockdown, something Phil initially bristled against. “It was bad enough living it,” he says, “I didn’t really want to write about it.” Building a whole track around just a tiny loop from her composition, however, it morphed into something that felt like it belonged on the album.

“Then I thought I better Google her and find out a bit,” he chuckles. When it transpired Coppé was an equally talented vocalist, she guested on the album’s final track ‘Moon Princess’ – her lyrics of a girl staying out to see the moon chiming with Phil’s own nocturnal tendencies.

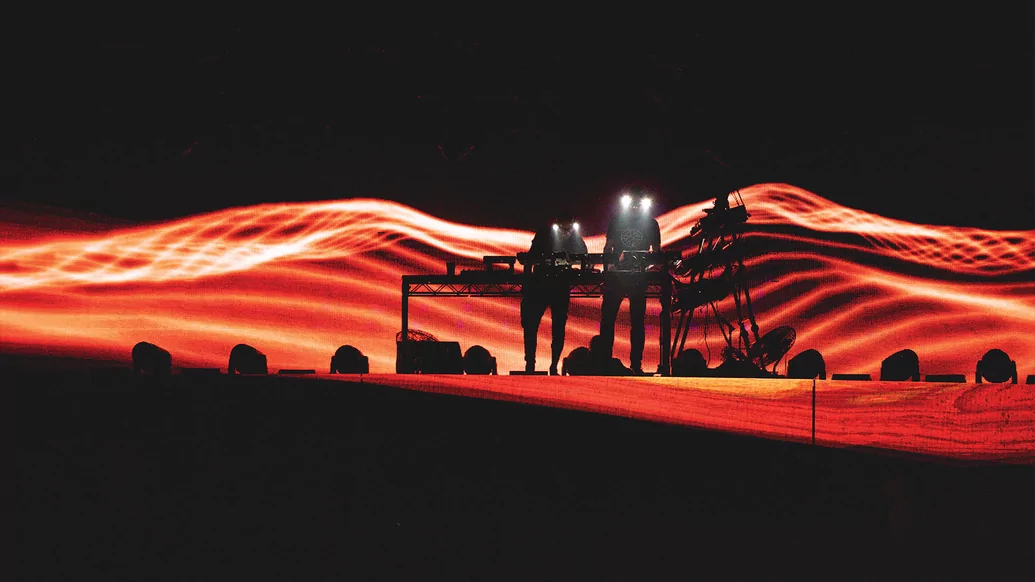

He and Paul are like “chalk and cheese”, he admits, which possibly contributed to why Orbital have split up twice in the past, first in 2004 and then in 2014. But their forthcoming UK tour, which kicks off on the 28th of March in Glasgow, then takes in Newcastle, Manchester, Bristol, London, Leeds, Cambridge, Nottingham and Brighton, marks the common ground where they stand firmly together — on stage. It’s also the beginning of a final return to normality, after their first two post-pandemic gigs were pencilled for Moscow and Kyiv. “We thought, ‘excellent, what could possibly go wrong?'” says Paul at their naive optimism around the world reopening.

“It’s the best thing,” reckons Phil on performing, “getting out there and seeing people.” He bought his first synthesiser after hearing ’80s groups such as Cabaret Voltaire pioneering a new electronic sound. And although Orbital rose to prominence during the post-acid house era, “we always wanted to be treated like an electronic band”, he says, citing the foundational Kraftwerk. While Kraftwerk have their uniform of red shirts and black pencil ties, Orbital’s torch glasses are a UK rave version, equally simple, iconic and unifying.

For Paul, playing live keeps Orbital’s back catalogue a vital, living entity. “‘Chime’, to anyone else, is a track that was recorded 30-odd years ago. It’s frozen in time. To me, it’s something that’s an ongoing, moving, creative piece. Every time I play it, I change it. It’s never quite the same twice.”

The tracks don’t just have their own individual lives, either. ‘Where Is It Going?’, which was written for the opening of the 2012 Paralympics and features the vocals of the late physicist Professor Stephen Hawking, became a surprise live favourite and has been their set- closer. But, says Paul, they’ll be moving it to near the beginning for their upcoming live gigs: “That’s going to totally put the cat among the pigeons, and I’ll play it in a different way.”

With their forthcoming shows featuring five or six new tracks, he’s sketched a rough order. But it’s not until they begin playing to an audience that they’ll know if it works or not, tweaking it until it does and continuing to feel out the dimensions of each track live on stage. “That’s what keeps it active in your brain,” Paul believes.

“I’m a bit of a prog rocker at heart,” he admits at one point, telling us how his plans to see Dutch masters Focus were scuppered by the various lockdowns — Covid’s legacy still being felt in the live arena. “I like stuff that jumps around and changes and surprises you.” It’s part of Orbital’s longevity, he reckons. Driven by a need to fill his tracks with various interplaying melodies, “your mind tends to focus on one. But then next time you listen to it, you might pick out the other one, and it just changes the way you hear it.”

“It’s great fun. Do an album, get a score. Hopefully, I can just keep doing that till the end of days, or until the apocalypse happens.” - Paul Hartnoll

While Paul has a passion for foundational groups such as The Cardiacs, he still finds inspiration in newer electronic artists, citing Anna Meredith as someone whose arrangements are “kinetic and full of life”. But as the previous inclusion in their sets of Belinda Carlisle and Bon Jovi samples shows, as part of their classic live version of ‘Halcyon’, Orbital are not averse to co-opting mainstream pop either. “The trick for me was, how can I make ‘Wannabe’ something that I like?” says Paul on a Spice Girls edit that was premiered in a mix for Mary Anne Hobbs last summer. The result is an “old school piano house, kind of rave anthem”, euphoric and melancholic in equal parts, its breakbeats leading into “all my usual tricks. I’ve turned them backwards and chopped them up and done all sorts of crazy stuff.”

It sounds Orbital through and through, but it’s still proved somewhat divisive. “Nearly all the women love it,” says Paul, “and half the men enjoy it. Then there’s the half of them that just scratch their head or look absolutely horrified and disgusted. Suck it up big boy, have some fun. Just try it. It’s like green eggs and ham.”

Ruffling a few feathers hasn’t ever dampened Orbital’s fortunes. They’d jack it in if the audience was no longer there, says Phil. But an influx of younger faces is filtering in. Co-headlining last summer’s Kaleidoscope Festival at Alexandra Palace alongside the Happy Mondays, “The dynamics were completely different. There were 20 to 35-year-old, dare I say it, youngsters. A lot of girls too, which never happened. I don’t know whether it was loads of kids whose parents had taken them to Womad, or something like that, the North London, Crouch End lot. They weren’t even born when we were writing some of these tracks, so that was brilliant, it was really encouraging.”

Ahead of setting off on tour, both are aware of how different it is now. “I’d rather do less production and keep the prices down than do full production and the tickets cost 50 quid,” says Phil. “I don’t know how much money people have got. I know it’s not good in my house,” he adds, telling us the current situation reminds him of the strikes in the 1980s. “I’m a firm believer in aspects of society,” says Paul in support of the public services that have been whittled away by austerity. “I like to have nice roads, I like to have a healthcare system, I like to know that I’m not going to be bludgeoned with an axe when I go out or get hunted down by a highwayman. I like feeling safe. But I think there’s a lot wrong with society. Advertising, what a fucking nightmare. People are in debt because they’re bombarded with advertising to have the latest, greatest fucking iPhone.” Perhaps this is the zombie apocalypse, he wonders, here already?

Instead of constant consumerism, we could be taught the message of minimalism: “You don’t need much to have a really happy life. And you don’t need to have as much as that person who’s got more money than you.”

Orbital’s future plans sound appropriately simple. “It’s just new music from me now,” says Phil. Paul, meanwhile, is working on a TV show for Channel 4, something he can’t say too much about, except that it’s “a comedy, drama, horror kind of thing”. After that, it’ll be on with another album. “It’s great fun. Do an album, get a score. Hopefully, I can just keep doing that till the end of days, or until the apocalypse happens.”