These photographs capture the excess and exuberance of New York’s ’70s disco scene

Bill Bernstein dedicated three years of his life to capturing the essence of the ‘70s New York disco scene. Here, Simon Doherty talks to him about some of his most iconic photographs, including images of Studio 54, Larry Levan, Odyssey Disco Club Dancefloor — made famous by Saturday Night Fever in 1977 — and more

The year was 1977. The disco scene was peaking, bringing with it unprecedented levels of euphoria. A specific set of sociological conditions (post-Stonewall riot, post-onset of the women's liberation movement but pre-AIDS crisis) manifested into an intoxicating mixture of liberation, freedom and expression. Society’s norms and values were being ripped apart and rewritten. Nowhere was this political upheaval more visible than on the disco-soaked dancefloors of New York City.

The eye of the disco storm at the time was one of the most legendary clubs ever, Studio 54. Nightclubs open and close all the time, but only a handful have redefined clubbing culture in some way. This was one of them. Long before documentary photographer Bill Bernstein spent 15 years on tour with Paul McCartney, acting as his personal photographer, he was commissioned by Village Voice to shoot a corporate event taking place in the daytime at Studio 54. He had never managed to get into the iconic club before. Like many of the legacy clubs (see: The Haçienda, Paradise Garage, Shoom, Berghain), entry was not easy, so he hid in the depths of the building, armed himself with Tri-X film, and waited for the regular club night to start. He was determined to capture the essence of whatever really went on at Studio 54.

Finding himself in the right place at the right time, Bernstein then dedicated the next three years to documenting the revolutionary dancefloors of disco’s peak and the characters that inhabited them. Following his ‘Last Dance’ exhibition at Defected HQ (which ran from 19th — 29th April) we asked him to talk us through some of his work from that time.

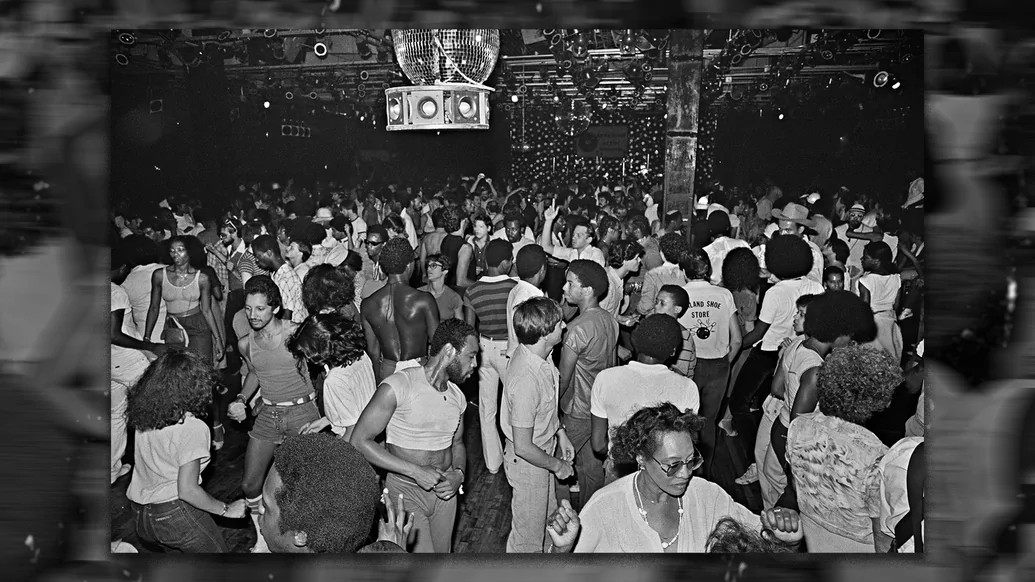

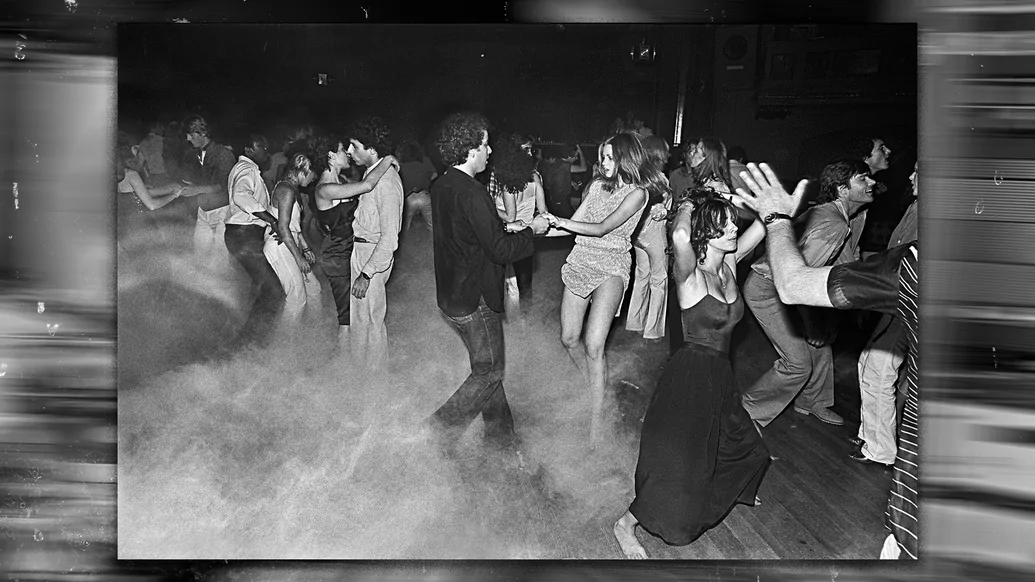

Paradise Garage, 1979

“It was a hot summer night, probably around 3:30 in the morning. It was really hot actually. I was standing on a little bleacher and watching the crowd. I remember feeling really high from the smell of poppers and the marijuana fumes in the air. I really caught a buzz just being there. I was hot, I was high, and the music and the sound system was amazing.

“As you were entering Paradise Garage from the street level, you went up this ramp. It was an old car garage, so it was a car ramp. But they had lights on the side that made it look like an aeroplane runway. You walked up the ramp with your group of friends and as you got closer to the second floor, you could start to feel the bass pounding through your feet and vibrating your entire lower extremities. As you got closer, you started to hear the noise. And then as you got to the door and the door opened, you would just be overtaken by the sound. Your whole body would shake, your head was buzzing.

“It was just packed with people. It would take me 10 minutes to get across the room because it was so packed. For that photograph, I found a place where I could actually go up a few feet and look down on the crowd. I really wasn't supposed to be taking pictures, but I sneaked a couple. And that was one of them. And being a little high and with it being so dark, I had no idea if I got a picture or not. I thought I might have [chuckles]. It wasn't until a day later that I saw the contact sheet and I was like, ‘Wow. That’s it.’”

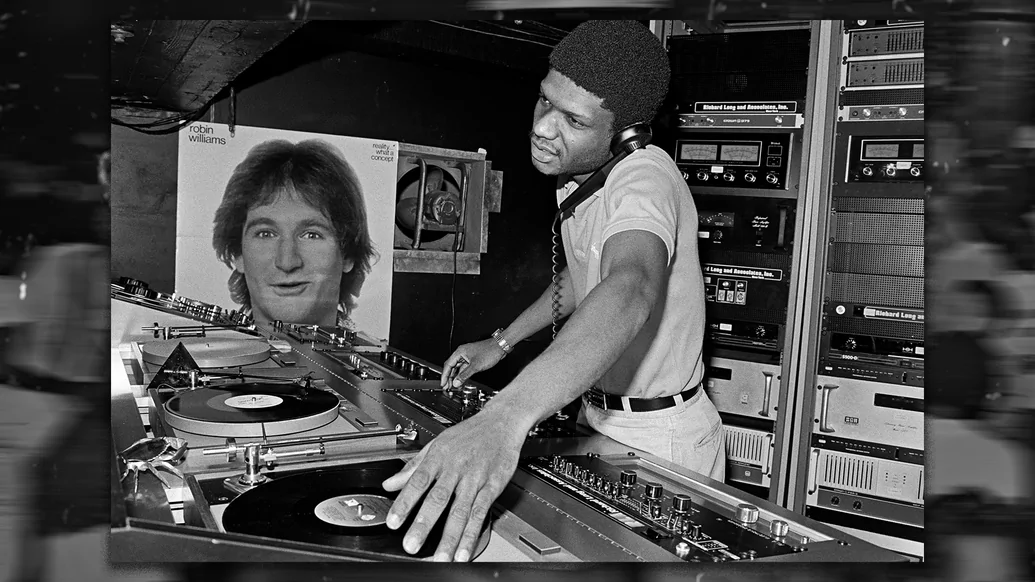

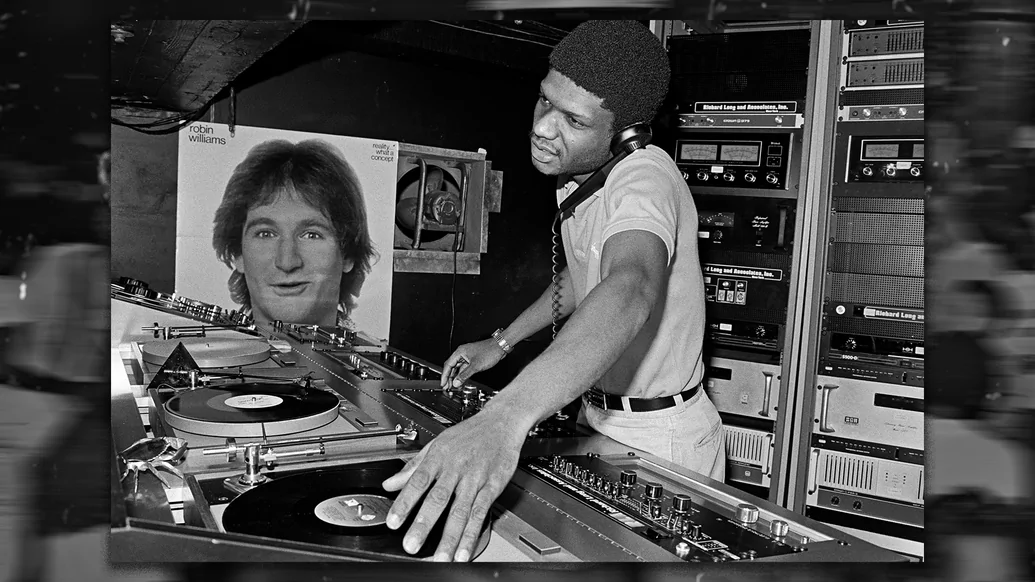

DJ Larry Levan at Paradise Garage, 1979

“That was taken at Paradise Garage. That’s Larry Levan. He was the guy, and he still is the guy, the DJ. That was taken because I had Village Voice credentials. I could talk to the people at Paradise Garage and say, ‘Hey, I want to go up to the booth and photograph Larry. Is that okay?’ I was allowed up there. So, I did that one night. I hung out with Larry for a little while and I just watched him work. We talked a little bit. The Robin Williams poster was an album that was pretty big at that time. And I don’t know why he had it there. I just assumed that he was really into Robin Williams.”

Why didn’t you ask him?

“Well, if I could go back in a time capsule I would ask that question. But, honestly, I was so focused on what I was doing, it was just there. I tried not to talk to him too much, because he was very focused and concentrated. I wasn’t doing an interview with him, I was a fly on the wall. I was just happy to be there. I knew that Larry was highly regarded during that time period. Today, he’s become, like, the icon of that time quite honestly. But it’s not something that you appreciate when it’s happening.”

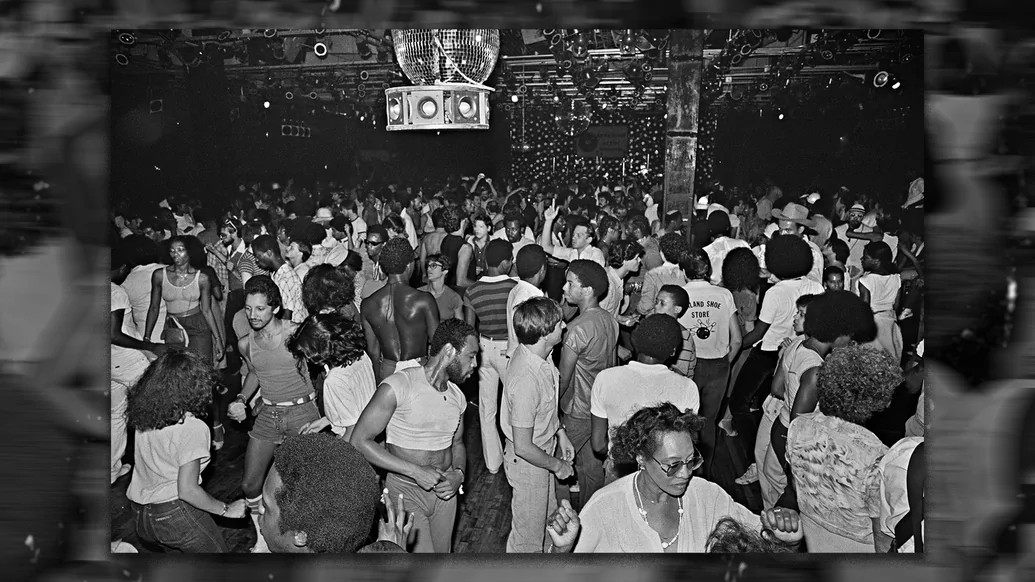

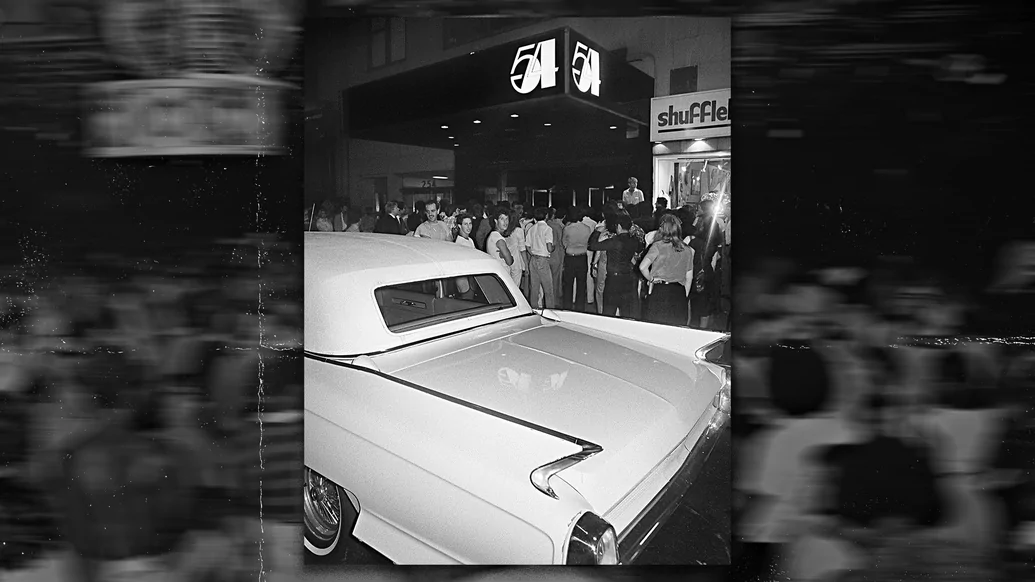

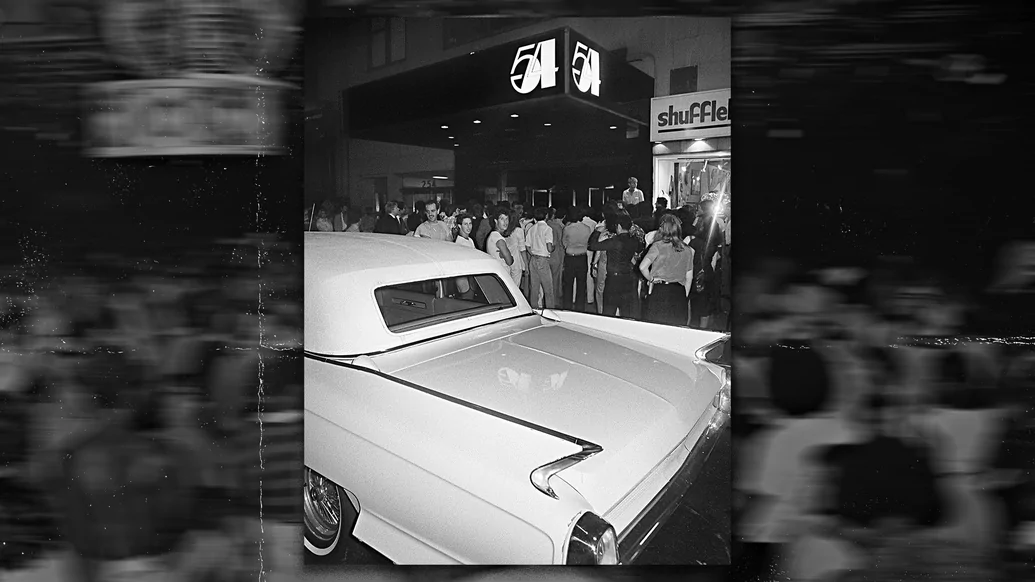

Studio 54 and Cadillac, 1979

“I think the idea behind Studio 54, which was masterminded by Steve Rubell, was to create a diverse party on the dancefloor. To him, that’s what made it so great and gave it its energy. He wanted the celebrity but also the marginalised culture in there. He wanted the cool celebrity too, not just anybody; some celebrities were charged to get in, others were just ushered in. He also wanted the right look, the right feeling. He was casting a perfect, inclusive party every night. He had the people to choose from. People were attracted to that place and wanted to get in. They would stand outside for hours with their hands raised trying to be let in.”

How did getting in work? Would you wait in line to be judged?

“There was never really a line per se, there was a velvet rope around the entrance and people would just spill out into the street as a crowd. And they’d stand with their hands raised. People would come over and say: ‘Hey, I know so and so. Can I get in?’ And [the doorpicker] would be like: ‘Mmmmm, let me check the guestlist.’ And it was probably a guestlist from like three weeks ago. Just any random list. And he’d say, ‘What’s your name, man? Nah, I’m sorry, I don’t see you... not tonight.’ Or they’d say, ‘It’s a special event tonight, you can’t come in.’ Which is bullshit. But people would still stand there, and then a car would drive up, an A-list celebrity would get out and be escorted right in. So you really wanted to be in there. It was like, what is this? What is in there? Andy Warhol said that it was a ‘dictatorship at the door and a democracy on the dancefloor’.”

DJ at Sybil's, 1979

“I wanted to see what was going on all over the city because clubs were popping up left and right. Sybil’s was a really mainstream club that was in the basement of a hotel in Midtown, New York. It attracted more or less the people from the hotel who were from out of town but it would also attract people from all over. A lot of people from the suburbs would go there. It was a very mainstream club. It had all of the decorations and disco balls and lights and all that kind of stuff.

“It had the only female DJ that I encountered. So I was pretty amazed by that. I don’t know her name. I’ve put it out through my social media that if anybody knows who this is, please let me know. I’d love to contact her. Clubs have already said, ‘Hey, if you can find out who she is, she’s welcome to play here.’ She was very unique. I think there were a couple of other female DJs at that time, but I never saw them.”

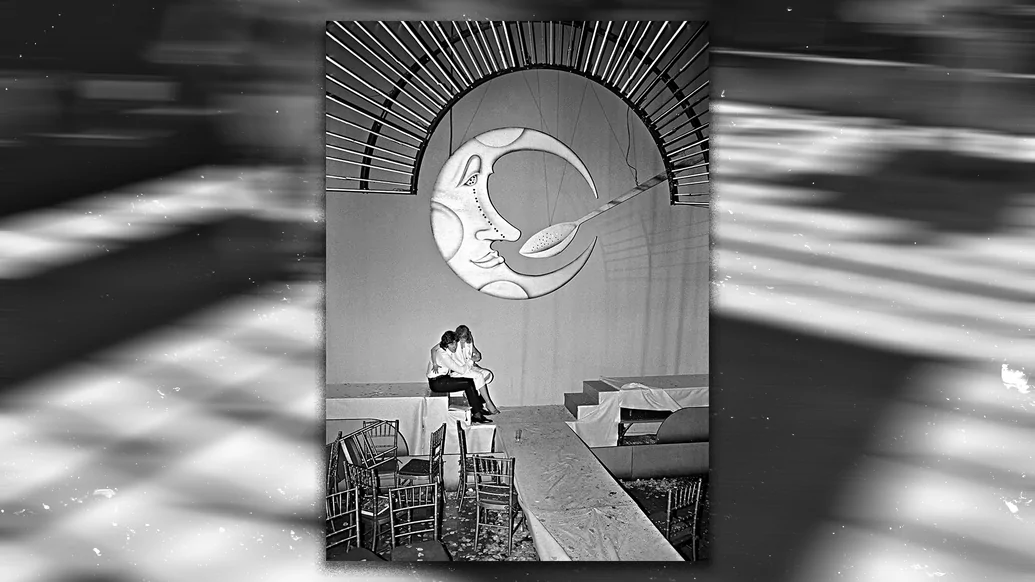

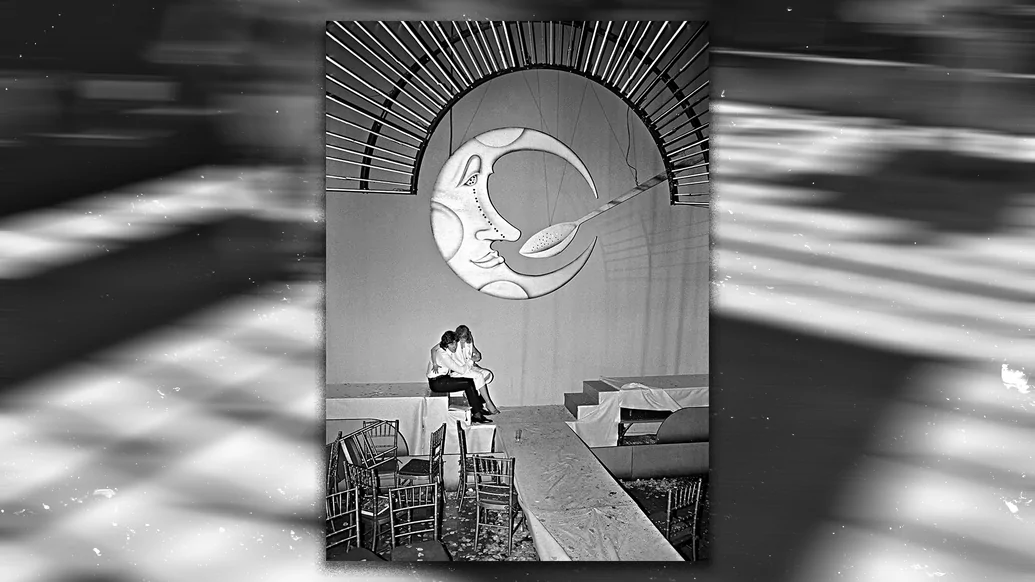

Studio 54 Moon and Spoon, 1978

“It was pretty different, it was spectacular. Because Studio 54 was an old TV studio, it had all the rigging setup for scenery to drop and lights. And it had a stairway up to a balcony. It was really set up to be a theatrical space. And they used it very well. Through the course of the night, they would drop different types of scenery. Of course, the famous moon and coke spoon that everybody knows. That, in itself, I thought was pretty amazing. Because cocaine was illegal, obviously, to actually put it in your face, like that — dropping this gigantic moving piece of scenery with a coke spoon going into the moon and into its eyes — was just incredibly ballsy. In your face, like: we’re here and we’re doing this.”

Xenon Dance Floor, 1979

“Xenon was kind of a copycat of Studio 54. It wasn’t as exclusive. It attracted its own crowd that was somewhat different than Studio 54 but along the same lines. You were kind of either a Xenon person or a Studio 54 person. There was nothing like Studio 54; that was on top of the hill, everything else was below. Xenon was trying to capture what Studio 54 had. It never really did, but it presented a really interesting night’s entertainment and it had all the bells and whistles.

“They were kind of located sort of near each other in Midtown areas in New York. Xenon attracted a straighter crowd, a little less theatrical. So in some ways, it was less about seeing and being seen. It was more about the soundsystem, the scenery, the get down and dance for the more mainstream culture at that time. It was less crazy. It had maybe less drugs (I’m not sure about that though, because drugs were so prevalent back then, especially cocaine and alcohol). It was more of a real disco versus the wildness of Studio 54.”

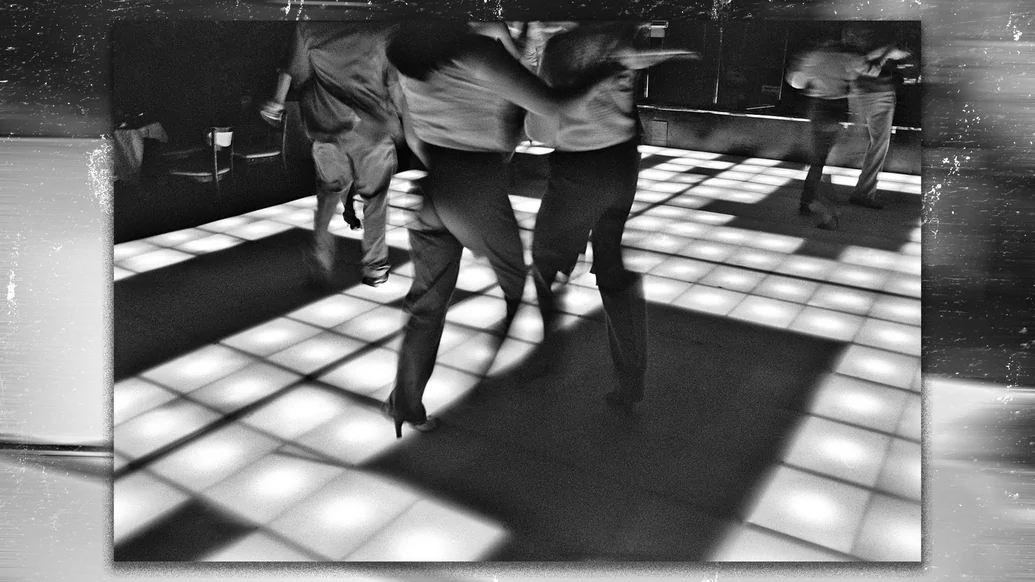

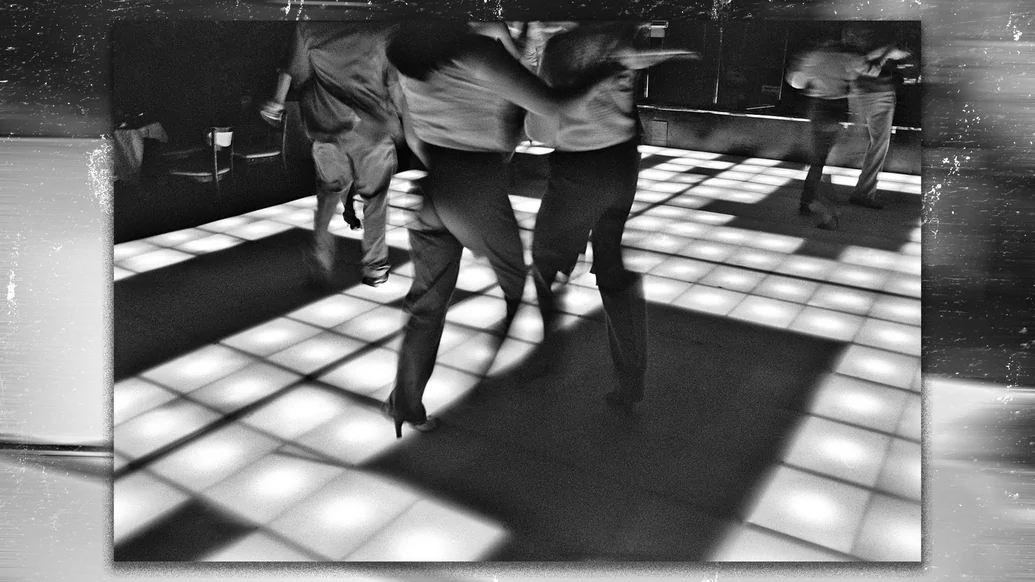

Odyssey Disco Club Dancefloor, 1979

“That is the place where Saturday Night Fever was filmed, in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. I felt like I had to go there just because in so many ways, it’s where it all started for the mainstream, with that movie and that dancefloor. Although it wasn’t necessarily a place of interest because of the cultural mix that was going on there, it was famous. And it was as I would have expected — a pretty white crowd of people from that general community in Brooklyn. No real diversity. Not a place of inclusion, but a place of history really. I thought that dancefloor was important; that’s what I really was drawn to. Outside of that place, on this big brick wall, someone had written in graffiti, ‘DISCO SUCKS.’”

So by the end of the 1970s, disco was getting a backlash?

“Exactly. We were getting the Disco Demolition event in Chicago, where disco records were burnt on the baseball field. Disco was starting to be on the way out, it was starting to get crushed under its own weight. There were TV commercials using kids dancing to disco music to sell, you know, toothpaste or something. It was just overly saturated in the music world, it was getting boring.

“The whole over commercialisation and the staleness of the disco sound was one thing. But there were other things [that ushered in the end of the era]: Things happened, at least I know in New York, around that time, that affected that whole scene. The most important thing that I know of was AIDS. That affected everything in terms of nightlife or people even going out mixing. It affected people wanting to be in a room with strangers. The queer nature of disco, that culture was primarily affected, certainly at the beginning. People just didn’t want to risk going to a disco so much.

“Then Studio 54 was shut down by the IRS [Internal Revenue Service], Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager were sent to jail for tax evasion. Once you take Steve Rubell out of the equation at Studio 54, you have a very different club. I mean, the club did exist during that time period and continued, it coasted on its reputation for quite a bit of time. But it wasn’t the same at all.”