We like to party: how pop became the sound of the underground

Pop has infiltrated dance music in a way not heard for many years. With DJs playing Britney Spears edits in Panorama Bar, bootlegs of Ciara, Spice Girls and Whigfield doing the rounds, and megastars like Dua Lipa commissioning club-tuned remix albums, there’s something going on. Chal Ravens asks: why now? What does pop actually mean? Is it all just part of a cycle, or is there something new happening?

POV: you’re in the middle of your opening set at Panorama Bar and everything is going right. Room? Steamy. Crowd? Loose. You’ve been playing your usual gear: bossy house, trancey belters, a shot of cold wave. Your taste? Eclectic, obviously — and you’re not afraid to draw for a quirky pop remix when occasion demands. So as a treat, you cue up something cheeky: a pumping house mix of Eurodance anomaly ‘Cotton Eye Joe’, which spends three minutes teasing its way to a single blast of the refrain. Crowd goes wild. When the outside world finds out, reactions are mixed: a club meme account salutes you, a Redditor calls it a crime against music.

More and more these days, pop songs are making incursions into underground dancefloors. But is playing Rednex in P-Bar taking it a grapevine-step too far? Marie Malarie has no regrets about the ‘Cotton Eye Joe’ incident — and anyway, they played a relatively classy remix of the line-dancing earworm — but they didn’t expect it to go viral. “It made me laugh at the start,” says the Polish-born DJ, who runs the Hysteria night at queer venue Dalston Superstore, “but then I hated it.” Meanwhile, plenty of DJs have been serving pop hits in their original cheesy flavour. This isn’t just club classics popping up in festival sets (though that’s reached epidemic levels). This is about hearing Britney Spears in Berghain, or Sonique at De School.

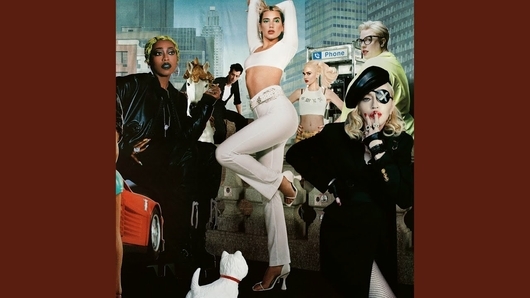

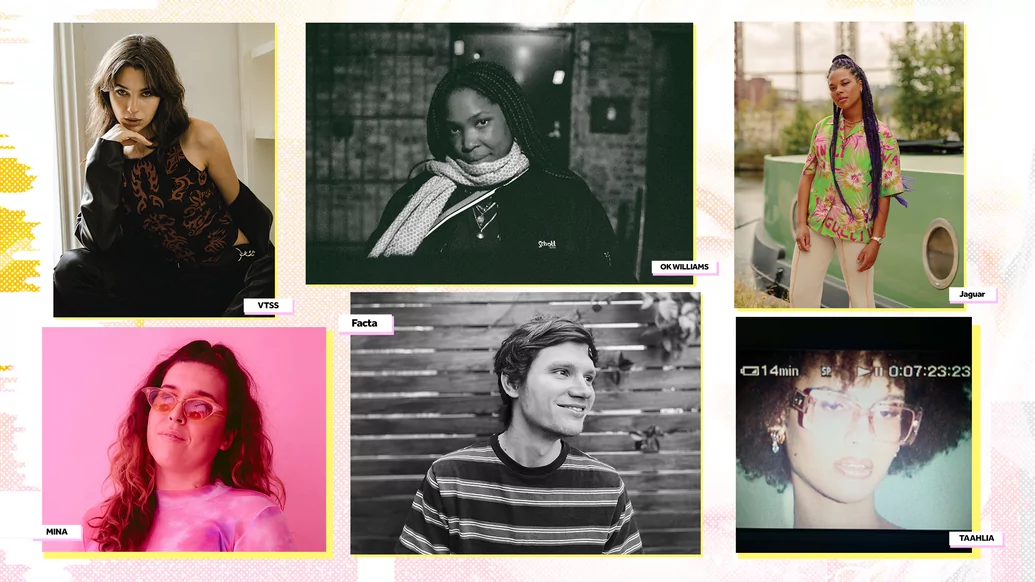

Producers are getting in on it too. Dua Lipa re-released her album as a DJ set mixed by The Blessed Madonna, with remixes by Yaeji and Midland and classic tracks by Larry Heard and Moodymann. Rian Treanor and Sim Hutchins managed to construct hyper-chopped edits of Whigfield within months of each other. The Kelly Twins, known for their deep-digging house sets, launched the alias Ghost Phone to release edits of Drake and Aaliyah hits. Even hard ‘n’ fast techno has been possessed by pop, with badsista, VTSS and LSDXOXO placing catchy hooks at the heart of their productions.

A smattering of dance tracks have invaded the charts this year too, from Pinkpantheress’ low-calorie pop take on Adam F’s ‘Circles’ to the surprise success of Eliza Rose and Interplanetary Criminal on ‘B.O.T.A. (Baddest Of Them All)’. That track went viral on TikTok before climbing to No.1 in September, making Rose the first woman DJ to top the charts since Sonique did it in 2000. So what is going on? How did the sound of the underground turn into ‘The Sound Of The Underground’? Or for the older millennials: what’s the deal with this pop life — and when’s it gonna fade out?

Several forces are at work. The rise of pop seems to be a response, perhaps even a reactionary one, to the recent history of dance music and its dominant modes and moods. It also appears to reflect the changing demographics of communities and scenes within dance music: the new faces in the DJ booth. There are generational considerations too, about the preferences of younger listeners, about the “vibe shift” we’re living through, and about the ways we actually listen to music, which have changed massively in the last 10 years. So let’s take it one (two) step at a time.

The vibe of the past few years has obviously been one of deprivation: two years of shuttered clubs, banned house parties and social distancing. Is it so surprising that when the lights came back on, we demanded to hear The Hits? That we wanted instant satisfaction more often than Discogs obscurities? Maybe that’s why Goldie finished his Primavera set this summer with a mashup of ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ and Coki & Benga’s ‘Night’, bringing the spirit of the student union to the beaches of Barcelona.

“Pop music has always had the power to bring people together, because of being recognisable, memorable and fun — or tacky.” – Marie Malarie

That incident brings us immediately to a point of clarification. What is pop? Are Nirvana pop? Can classic dubstep be pop? Is pop in fact more of a tag than a category — an index of popularity rather than a recognisable genre? Basically, yes to all the above. If it’s on the speakers and you’re all singing along, it’s pop. On the dancefloor, pop is largely about recognition: this is a song we all know. “Pop music has always had the power to bring people together,” says Malarie, “because of being recognisable, memorable and fun — or tacky.” But we’ll come back to this.

The pop phase we’re going through didn’t begin with the end of lockdown. It’s hard to imagine now, but 15 years ago, dance music was basically a niche interest, overlooked by style mags in favour of slim-fit indie acts, retro crooners and electropop. The pendulum began to swing back towards the dancefloor sometime around 2011 when a new generation discovered the joys of “proper” house and techno: analogue gear; vinyl records; arguing over the meaning of “deep house” and whether that included Disclosure.

In the last five years, notable underground movements included deconstructed club (where pop vocals played a constant and subversive role), the evolution of hard and heavy US club styles like footwork and FDM, and the vague terrain that journalist Simon Reynolds described as “conceptronica”. His term was divisive, but the years before the pandemic were certainly well-stocked with serious records that mingled cultural theory with AV spectacle.

In the dance mainstream, the last decade was dominated by brash EDM in North America and festival-friendly house and bass in Europe, plus the dark, hypnotic strand of techno that drew clubbers to Berlin, Tbilisi and Kyiv. Now pop music tastes like sparkling refreshment after a decade of black-clad uniformity and the macho insularism of analogue techno and rare white labels, which flourished in the mid-2010s on labels like L.I.E.S. and LA Club Resource. Black T-shirt techno now feels past its sell-by-date — or worse, kind of mainstream.

“There’s something truly fascinating,” tweeted Polish producer VTSS recently, “about techno fans going to a big room event with the biggest paid djs in the industry on the line up and calling anything else that’s not big room techno sound ‘commercial’. Can we just move on and stop claiming how niche & obscure it is just cause that 20k paid dj is wearing all black outfit [?]”

As a decade of techno appreciation fades into the past, those with longer memories are thinking back to the big dumb fun of the era previous, from blog house mashups to the chart-dance hits that used to make it onto the radio: Basement Jaxx, Kosheen, Layo & Bushwacka. With the return of the “indie sleaze” aesthetic, as signalled by the success of Meet Me In The Bathroom, Lizzy Goodman’s oral history of the NYC scene in the ’00s, it’s no wonder other Noughties-loving feelings are swelling within us. It’s now 20 years since 2ManyDJs released their millennial mashup manual ‘As Heard on Radio Soulwax Pt. 2’, yet tickets to the London anniversary gig sold out in a flash.

Like the width of a trouser leg, musical trends don’t just swing back and forth without evolving. Even continuity projects absorb changes in technology, other genres or society at large. Think of the new school of junglists, including SHERELLE, Fracture and Itoa, who have synthesised influences from genres like footwork and Baltimore club while staying true to the form. Revivalism typically brings with it some fresh adaptations.

With that in mind, one of the most profound and visible changes to dance music over the past 10 years (or even five years, really) is the success of women, queer and trans DJs in previously male-dominated spaces. The diluting of straight male DJ representation has done more than just level the playing field — it has changed the kinds of records that get played.

DJs emerging from queer scenes typically bring their own musical reference points and community lore: disco classics by Diana Ross, Donna Summer and Sylvester, passed down through generations. Camp divas and hot mess anthems by Christina, Britney and Gaga. Cheesy pop and “guilty pleasures”, the kind that weren’t taken seriously or accepted as cool by the male gatekeepers of our youth. And on top of that, for the queer DJs who wouldn’t touch a Whigfield record, endless crates of pumping house and classic rave ready for détournement, their lyrics on freedom, sex and desire alchemised into mantras by trans DJs like Eris Drew and Octo Octa.

Malarie recalls seeing her queer friends laughing and singing along to ‘Cotton Eye Joe’ in P-Bar and points out that the track was chosen “purposely, realising that it might be badly received by some dancers. Important fact: if the crowd was 100% queer, I’m pretty sure that every single raver would have loved it.” Playing a record so flagrantly tasteless in a place “considered to be a temple of dance music” was intended as a rejection of “the seriousness that accompanies [the] contemporary club scene,” they add.

“If you can’t have this cute pop moment where everyone is singing and having this euphoric moment, then maybe this set is not for you." – Bored Lord

For Daria Lourd and her community of DJs and dancers in Oakland, playing pop is “a way to deter the pretentious dance music people real fast”. Under the name Bored Lord, she’s a prolific producer of club bootlegs and party breaks on labels like Knightwerk and T4T LUV NRG. Queer audiences are always subverting their favourite music, she notes, whether it’s “latching onto pop divas or loving nu metal”, and their appreciation ultimately changes the meaning of those sounds.

“So yes, it’s a pop song — but it doesn’t mean what the artist intended it to mean, and we’re re-contextualising it,” Lourd says. On a recent edit pack (released for 24 hours only to avoid legal drama) she took her tools to a revered R&B classic as well as a deeply uncool adult-contemporary hit. Her choices are driven by catchiness, mainly: “If it’s stuck in my head, can I find a good edit? And if I can’t find it, I’m gonna make it.”

As well as trying to create “a cute singalong moment” on the dancefloor, Lourd uses her edits to pose the question, “How do we make this girlier?” The meaning of “girly” has more to do with testing the crowd than playing Britney hits. “I sometimes sense the crowd shift by the end of my set. I push some people out because they’re like, ‘Wait a second, I didn’t think I was gonna hear a Slipknot edit’,” she laughs. “I play Sonique ‘Feels So Good’ every set and it’s kind of a test. You think I’m doing this technical DJ stuff, but if you can’t have this cute pop moment where everyone is singing and having this euphoric moment, then maybe this set is not for you.”

So pop doesn’t just mean cute, frothy fun — it might mean Slipknot, in Daria’s case. In a 1979 issue of Gay Left, a socialist journal for gay men in London, the film critic Richard Dyer made the point that “the anarchy of capitalism throws up commodities that an oppressed group can take up and use”. He was talking about disco, which at the time was being targeted by white rock fans via the notorious “Disco Sucks” campaign. Forty years later, we can see the maligned genre of nu-metal — ultimate soundtrack to millennial outsiderdom! — getting love from queer artists like Bored Lord, Asmara and Le1f, who happily spin blasted edits of Korn, Linkin Park and even Christian rockers Flyleaf.

Even “pure” pop offers infinite subtleties for DJs to explore. On one of her edits, Bored Lord isolates the vocal on ‘Hit Me Baby One More Time’ and flips it into cloudy electro. When OK Williams closed her own Panorama Bar set with ‘Gimme More’, a moody stomp from Britney’s paparazzi-era album ‘Blackout’, she conjured a vibe that’s simultaneously camp, tragic and victorious — all the more so since Britney’s release from her patriarchal conservatorship. Facta, a London producer of wonky club rhythms, turned that narrative inside out on his “iso mix” of ‘Piece Of Me’, another song from ‘Blackout’, letting her pained vocal (“I’m Miss American Dream since I was 17”) float free.

Another factor accelerating this pop moment is the impact of so-called “hard dance” — also the name of a Boiler Room mix series which launched in 2019. After the jungle revival of the 2010s, a whole crop of DJs (many of them women, including Nkisi, Chippy Nonstop and Spinee) have been bringing back the speed and intensity of breaks, gabber and hardcore techno. One strand of this hard tendency is indebted to the wacky samples, big drops and crash-bash blends of UK rave, where pop music is a natural accompaniment. That niche is famously celebrated at the annual Bang Face gathering in the north-west of England, where festival boss James St. Acid drops breakcore edits of Gayle’s sweary teenybop ‘abcdefu’ and Trance Party chief Evian Christ blends Madonna’s ‘Music’ into his ear-splitting set.

A sense of humour is crucial to this chaotic mode, a world away from the smooth transitions and durational extremes that have characterised the middle lane of the underground for years. It’s no coincidence that this rebooted hard dance scene can feel distinctly queer, too — from London’s nu-goth crew Gutterring to Polish gabber fans Wixapolonia to São Paulo club crew TORMENTA. The internet label WEIRD NXC pushes the hard-pop idea even further, with trans artists like TAAHLIAH and Laura Les releasing face-melting nightcore and gabber-poisoned bootlegs of Ciara, Darude and (god help us) Owl City. The more annoying, the more exciting.

The continuing absorption of US regional club styles like Baltimore and Jersey club, footwork and FDM has been crucial to this evolution. Samples are still the building blocks of these Black genres, and for a generation of DJs influenced by the likes of Brick Bandits, Rod Lee, Teklife or even foreign acolytes like Night Slugs — plus a whole school of experimental club DJs in the US from Total Freedom to the Fractal Fantasy crew — the use of pop samples is fundamental. Go back further and any ‘90s house fan will remind you that CD singles used to be packaged up with club remixes as standard, including rock releases — think of Armand Van Helden’s dark garage take on Sneaker Pimps’ ‘Spin Spin Sugar’, one of Bored Lord’s favourites.

We’ve so far noted the arrival and revival of queer club culture and hard dance styles, and the post-pandemic rejection of “serious” techno. Our next stop is more historical. We know that generations are short in dance music; a new one comes along every five years or so, as a fresh cohort of 18-24 year olds impose their own style and preferences on their elders. The current generational shift is bringing with it a more profound erasure of the kind of musical distinctions that were once crucial to being a fan.

If you’re under 25 now, you grew up without such a deep sense of allegiance to genre as your older siblings and parents. And where millennials grabbed onto the ends of a fraying physical industry, Gen Z has barely had the chance to buy physical records. Vinyl manufacturing and distribution has gone to shit in the last few years and artists and labels have migrated onto Bandcamp, to the detriment of existing physical and digital stores where genre divides were once paramount to buying and selling. Bandcamp itself is a crucial source of pop edits, providing an under-the-radar global shopfront for artists making illegal bootlegs. Whether you’re after vinyl-only Spice Girls junglism or B-more-style flips of Nelly Furtado, Bandcamp is the first port of call.

All of this means that the concept of ‘pop’ — as a marker of the commercial or the uncool — has become increasingly unstable. Since the writer Kelefa Sanneh made the case for pop in a much-discussed 2004 essay, poptimism has saturated the discourse around popular music. Poptimism, in an utshell, is a critical position that takes “manufactured” pop music seriously as an art form, in all its superficiality and commercialism, while rejecting the “rockist” veneration of attributes like musicianship and authenticity.

Reframe that argument for dance music specifically, and things get weird. Techno and house end up in the “rockist” category — despite their origins in queer culture and radical Blackness — because of their relative emphasis on tradition, craft and underground legitimacy. In contrast, a dancefloor poptimism would celebrate the immediacy and femininity of a Dua Lipa remix, a sample-heavy Jersey club track by UNIIQU3, Robyn’s electropop, or a tongue-in-cheek nightcore edit of a video game soundtrack.

But like rock music, techno and house were not invented by the white men who took it over and claimed it as their own. It’s worth noting that some of the most celebrated music in the poptimist canon is fronted by white women— Kylie Minogue, Robyn, Carly Rae Jepsen — and problematically described as “pure” pop, in a racist comparison with chart-topping music by Black artists. When pop is perceived as an actual genre rather than an index of popularity, Black artists lose out. (Note Tyler, the Creator’s frustration at having his Grammy-winning album ‘IGOR’ placed in the Best Rap category. “It sucks that whenever we — and I mean guys that look like me — do anything that’s genre-bending they always put it in a rap or urban category. I don’t like that ‘urban’ word — it’s just a politically correct way to say the n-word to me,” he said. “Why can’t we just be in pop?”)

Poptimism’s significant achievement was forcing critics to view pop as an innovative, experimental space — often more so than “indie” scenes. That inverted logic had some unexpected results. One of them was London collective PC Music, which repelled plenty of critics in the late 2010s with its apparently ironic interpolation of pop, trance, J-pop and other “tacky” (and indeed, female-coded) genres. Ultimately the PC Music credo was behind some of the most formally innovative music of the era, notably from PC affiliate SOPHIE. SOPHIE's own take was making mainstream pop music “because it lives in the lives of so many more people. It’s not exclusive, it’s not elitist,” as the artist explained in 2018. When SOPHIE's heroes Autechre remixed ‘BIPP’ in 2021, a bizarre horseshoe theory of the poptimist avant-garde was complete.

But poptimism can be a blunt tool. It invites us to love the silly and the superficial, to be impressed by fame and doing numbers. It’s no surprise, really, that dance music today is defined by (superstar) DJ culture. Dance music is more personality-led, more showbiz, more straight-up visual than it has been for years. And when DJs rely on their follower numbers for bookings — which is a sad reality at a certain end of the scale — they do all kinds of things to satisfy “the algorithm”. If a DJ was hoping for a viral moment in order to boost their profile, for instance, they might decide that pulling out a pop song in an unusual context is a risk that’s worth the reward. When Radio 1 DJ Jaguar dropped a donk edit of the Vengaboys at The Warehouse Project recently, she managed to hype the crowd and bank her biggest TikTok by far (76.5K views).

Panorama Bar has been pulverised by the mainstream more than once this year. In August, Daytimers figurehead Yung Singh used his four-hour set to go on a journey from 130bpm to 170bpm, moving through house, garage and techno before arriving at the drum & bass section of his crate. At that point, he decided to pull out Chase & Status’ arena-sized whammer ‘No Problem'. “It’s a top drawer drum & bass track by itself,” defends Yung Singh. “Everyone went nuts. I can’t really tell if that’s ‘cause they knew the track or they liked what they were hearing — I was just focusing on what to play next.”

Other pop weapons in his crate include a Vengaboys refix by Afro-funky advocate Mina (“It’s at 110bpm but I pitch it up to 150 and throw it in when I’m playing trance or speed garage”) and Jennifer Lopez’s ‘Waiting ForTonight’ (“a really good house track – it gets people moving and everyone knows the vocal”).

Though he’s known as an archivist of ‘00s Punjabi garage as well as a cheerleader for the British Asian dance underground, Yung Singh takes a pragmatic view on the role of pop music. “Your job as a DJ is to get people moving. You have to play to the crowd and not see yourself as above the crowd, but equally you want to show them new stuff,” he says. “Throwing a more mainstream track into the middle of a heads-y set is a way to do something fun, not take yourself too seriously and still be an artist.”

“Throwing a more mainstream track into the middle of a heads-y set is a way to do something fun, not take yourself too seriously and still be an artist." – Yung Singh

Malarie agrees that the rules are there to be broken. DJs should “find new ways to surprise and entertain the audience,” they say, “and I think that’s what the UK music scene is about — diversity, open-mindedness, inventiveness and a good sense of humour. That’s why I love it so much.”

So what have we learned? Maybe most importantly, that pop can’t be nailed down. Because at the same time as “pop”, in its various manifestations, is enjoying a presence and status in dance circles it hasn’t done for years, actual pop is having a crisis. The shift to streaming has thrown the record industry off balance, as the needs of platforms like Spotify and TikTok end up sparking new styles and formats. “It’s a bigger and more level playing field, and everything is getting lost,” pop manager Chris Anokute told Billboard recently. “Everyone’s an artist, but almost nobody’s breaking."

Big labels are struggling to create new stars. Traditional genre boundaries are dissolving, with the model customer steered towards choosing music according to mood, activity, time of day or viral impact. Ironically, all this is the case in the year that two of the world’s biggest artists released albums that were defined as dance music: Drake’s ‘Honestly, Nevermind’ and Beyoncé’s ‘Renaissance’.

Pop music isn’t a static sound or a genre — it’s a format, a measure. It demands “endless, purposeful reinvention,” as New Yorker critic Amanda Petrusich puts it. Perhaps we can think of dance music as something other than a genre too: more like a community in constant conversation with itself, upholding its own rules and expectations, all of which are subject to constant subversion and realignment. Right now we’re in some kind of celebratory-yet-nihilistic mode, gorging on high-fructose pop in the hope that some of its joy and hope will wear off.

As Petrusich also pointed out in an essay marking the 25th anniversary of ‘Spiceworld’: “The Spice Girls’ mission was to spread a kind of anodyne, generalised positivity; in 1997, this may have seemed like a timeless goal, but, 25 years later, it’s probably what makes ‘Spiceworld’ feel the most dated.”

Who knows what we’ll be craving in another five years? The pendulum will probably swing back at some point, in some way. My long-term advice? Buy up modular synths and the Ostgut Ton back catalogue. In the short-term? Get yourself on the Vengabus.