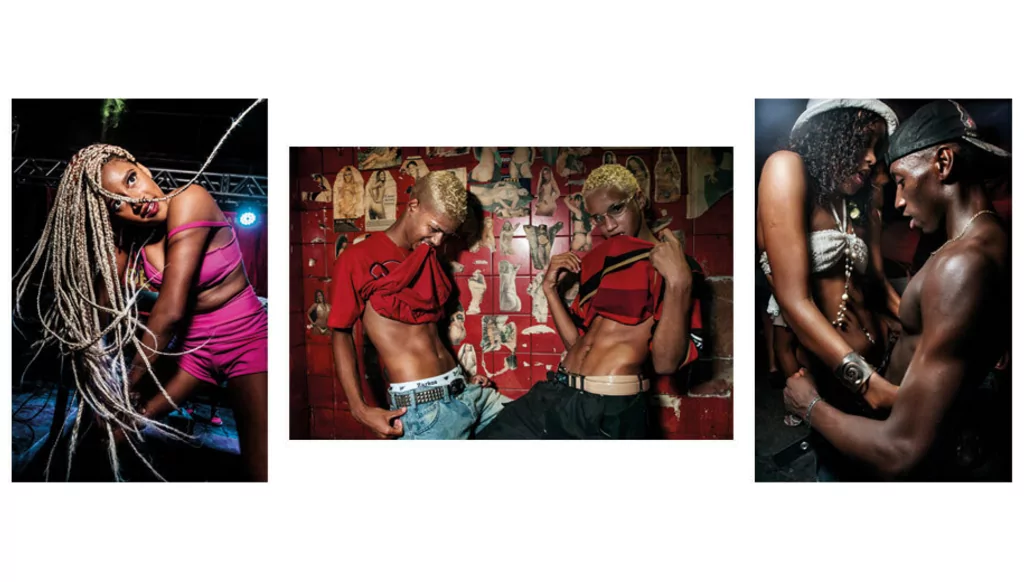

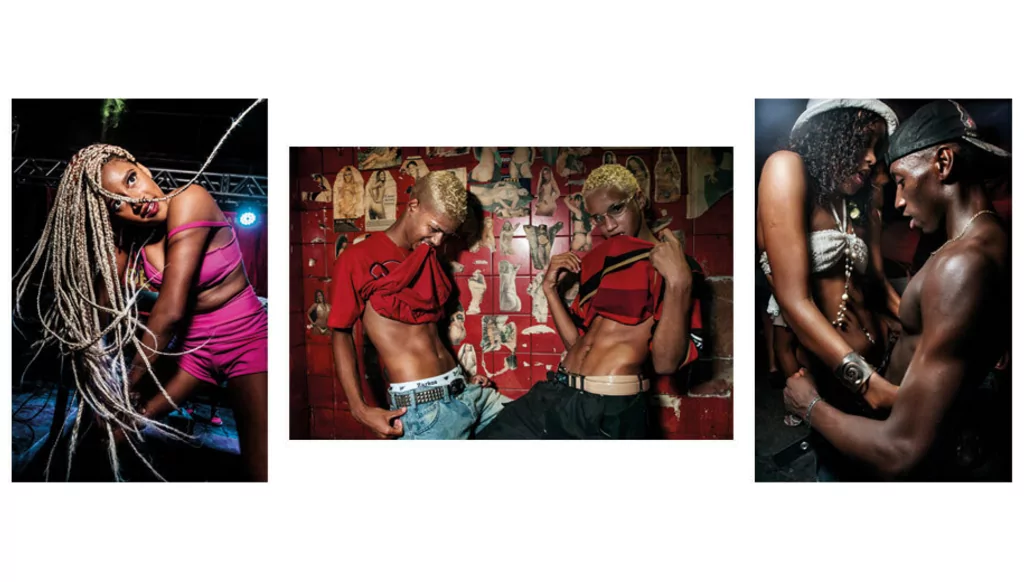

Baile funk: the criminalisation of Brazil's funk scene

Baile funk is a phenomena of Black Brazilian music. But despite a huge fanbase and cultural influence, funk is often criminalised in Brazil because of its origins in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Raphael Tsavkko Garcia explores the history of the baile funk scene to discover why it’s so celebrated — and criminalised

In the early hours of Sunday 1st December 2019, militarised police broke up a Brazilian funk street party called Baile da DZ7 in the São Paulo favela of Paraisópolis. The party-goers were kettled into narrow alleys and, while trapped, the police used tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse the crowd, which led to a trampling amidst the chaos. Nine people were killed. Gustavo Cruz Xavier was the youngest to die. He was just 14. According to witnesses, the police occupied all possible exits from the street, making it difficult to escape and leading to the panic.

Many of those who managed to escape were chased down by the police. (The police claim they were chasing armed drug traffickers, but there is little evidence to support this currently.) It was another chapter in the long process of criminalising funk music in Brazil. Despite achieving worldwide success with singers like Anitta and Ludmilla, funk continues to be heavily policed in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, and its artists and producers have been constant victims of lawsuits, criminal investigations and even imprisonment.

ORIGINS

Brazilian funk is an “Afro-diasporic genre of electronic dance music born in Brazil in the late 1980s,” explains Carlos Palombini. He’s a Professor of Musicology at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), and one of the genre’s foremost experts. “It combines Afro-American and Afro-Brazilian musical traditions, and belongs to the vast group of derivatives of the musical language of hip-hop, with marked references to electro, Latin freestyle and Miami bass.”

Along with these styles, funk brings together a variety of other musical, vocal and dance influences from Brazilian popular culture: samba, pop-rock, football stadium chants, Maculelê (a Brazilian folk dance of Afro-Brazilian and indigenous origin) and capoeira (a form of martial arts, developed in Brazil by the descendants of African slaves). These styles are embodied in the figures of DJs and MCs, drawing from Jamaican soundsystem and hip-hop culture. Rafael Hermés, a MA researcher/student at University of São Paulo, explains that “funk mixes rap with the Brazilian accent, and the melodic profile of local song genres... finding various poetics that express the life, desires or trajectories of the young, Black and peripheral population.”

As a racial and sonic melting pot with working class roots, funk has long clashed with the social norms of the Brazilian elites. “It challenges the standards of understanding of musical nationalism,” Professor Palombini explains. It’s a genre that both details and creates a difficult relationship between the social classes, which often leads to violence. Someone who speaks to those populations is DJ Marlboro — widely considered the inventor of funk, with the release of his 1989 album ‘Funk Brasil’.

“Funk is union,” says DJ Marlboro. Its social importance in Brazilian culture comes from the fact that the music “gives opportunity to those who are socially excluded. We’re bad with education, health and security. We are a very rich [yet] poorly administered country,” he continues. “The problem in Brazil is that the political class is trying to take advantage [of us] — of a country that has been robbed ever since it was discovered. The more miserable the favela, the more violent it is. The more urbanised the favela — with more assistance, better schooling — the less violent it becomes, because people have perspective in life. And funk helps to give perspective. Funk can lead to social ascension.”

SAMBA

There's no way to understand funk without seeking the roots of another Brazilian genre and culture. Samba emerged in the period immediately after the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888, and was strongly associated with the marginalised Black population. Thousands of freed Black people built their homes outside the cities, in what became the favelas, and samba is indigenous to those communities. Almost predictably, samba was quickly frowned upon by the contemporary Brazilian, largely white, elites.

“Samba built around itself a certain association with mischievousness,” explains Gabriel Borges, a PhD student of literature, focusing on Brazilian music at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. He says that being found on the street with a guitar was reason enough to be arrested, as was the practice of capoeira; closely linked to both samba and funk, the form of martial arts was also criminalised at the time.

Samba and funk have two main elements in common. There’s social revolt and sometimes even praise for crime, as a social response to exclusion. There’s also social elevation, a way for artists to use music as an attempt to integrate and succeed. As Borges explains, samba, as well as funk, represents “the aspirations of the Black population to integrate into [wider Brazilian] society, intending to overcome this marginalisation.” Antônio Spirito Santo, a musician and expert in the history of samba, summarises the relationship between samba and funk, and the elites, as “resilience”: neither a radical reaction, nor a complete integration.

DEVELOPMENT & CRIMINALISATION

DJ Marlboro explains that the music was produced in the favela, and that it was “sung on the asphalt (a term for those who live outside the favela), asking for peace.” But the wider success of funk started not in the streets of the favelas themselves, but in club dances, or bailes, throughout Rio de Janeiro. In the clubs, there was the ‘festival de galera’ (crowd festival), where groups would compete at dances to funk songs “in a style similar to Samba”, he says. Fights were forbidden in the bailes, and those involved were often kicked out. But fearing that they’d lose the loyal crowd by continuing to do so, promoters realised that “the dance that was a healthy competition began to be attended by those who wanted to fight,” DJ Marlboro says.

Over time, a culture known as bailes de corredor, or “corridor”, grew. Rival groups organised themselves on either side of the club: forming corridors, aka lines of people, linking arms, until it started to be seen “as a game, almost like [martial arts-style] capoeira”; not dissimilar to a mosh-pit in rock music, as dancers-as-fighters would sweep through the crowd.

The corridors gradually became less about personal fights or gang violence, and more a part of funk’s culture. DJ Marlboro even considered talking to the Brazilian Olympic Committee to transform the dances into a nationally recognised sport. The problem, he says, was that the police became aware of the bailes de corredor. “Not knowing how it worked, the authorities ordered all the dances in the favelas, in 1995-1996, to close,” he explains. “They ruined integration and confined [funk] only to the favela,” where criminal groups could exercise more control.

As funk was pushed back to the favelas, an intense media scrutiny furthered its criminalisation, says Professor Palombini. “A turning point [was] the so-called arrastões of 1992,” he explains, “exploited by [national TV network] Globo Network for electoral purposes.”

An arrastão is when a large group of people start carrying out robberies in the same location, in a coordinated and quick assault. The arrastões of 1991 and 1992 in particular were notable because they were the focus of intense media scrutiny and derision, linking the Black favela population to the robberies. In October 1991, the GLOBO newspaper reported on the arrastões with the headline “Beach rats drag fish and exchange shots in Ipanema”, a Rio de Janeiro beach.

Many within the funk scene argue that the media reporting of the early '90s arrastões is part of the history of the criminalisation of favela residents, and by extension funk music. They were "manipulated by the media, since there were no robberies, but ‘corredores’ [a violent act that doesn’t involve theft],” says DJ Marlboro. The presence of young, mostly Black favela kids on the beaches was framed as an attempt to occupy a space that the elites considered to be their own — an “invasion of barbarians” on “civilised” city life, says DJ Marlboro. When these kids fought each other on the beaches, the quick, palatable answer to the elites was to blame the favelas and criminalise their culture.

Throughout the 1990s, bills were presented in Rio de Janeiro seeking to investigate funk performers and ban events. In 1999, the CPI (Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry) was created in Rio de Janeiro’s State Legislative Assembly to investigate funk music and culture. One year later, a law was passed that forced promoters to (among other elements) install metal detectors and have military police guards at bailes, and get written permission from the government to host bailes. Most ominous, music that “promoted crime” was banned from being played at bailes, criminalising performers as well as promoters.

“The term ‘funkeiro’ became synonymous with ‘criminal’ in the media,” says Professor Palombini. “During the first decade of the 21st century, the same legislative assembly in Rio de Janeiro [enacted] no less than five laws to regulate balls,” Palombini explains. “Meanwhile, attacks by the Military Police on favela balls proliferate, and police inquiries like that [in] 2005 — with names and photos of MCs stamped on the covers of the tabloids.”

These laws flip-flopped throughout the ’00s. In late 2003, harsher elements of this law were repealed, deeming baile funk a “popular cultural activity”. This law was in turn revoked in 2008, with a new focus on criminalising larger raves, and then revoked again in 2009; law 5543 deemed funk performers as “agents of popular culture”, and that “any type of discrimination or prejudice, whether of a social, racial, cultural or administrative nature against the funk movement or its members, is prohibited".

The result of this policy of persecution, by the media, police and politicians, was that the bailes — already confined to the favelas — became more difficult to organise, until, ultimately, the Police Colonel had the power to decide whether or not a baile could take place in a favela at all. “Funk lives under dictatorship,” Palombini laments.

This phenomenon of criminalisation led to the emergence of a subculture (and sub-genre) known as “proibidão” (very prohibited), with lyrics that praised drug traffickers and crime, further contributing to the marginalisation of the genre. Funk touches on subjects that are taboo to a conservative society like Brazil: talking about sex in an often pornographic way, and portraying crime from the perspective of victim and perpetrator. As DJ Marlboro explains, funk is “the favela singing to the favela. Singing about its situation; be it violence, sexuality, exclusion... that’s where proibidão is born. It’s born because of the prohibition of funk in clubs.”

“Funk has taught me to think, to reach places I never imagined. Funk is an inspiration for those that live in communities, to have opportunities, to learn.”

A SHOCK PROSECUTION

The 2019 arrest of DJ Rennan da Penha — a key funk figure and promoter of the wildly popular Baile da Gaiola — shocked the scene. The prosecution claimed that he acted as a “scout” for drug traffickers, warning them of police movement inside Complexo da Penha, his home favela and the site of Baile da Gaiola, through WhatsApp messages. Rennan maintained his innocence — particularly against the central claim that he’d worked with and taken money from drug traffickers in order to fund the hosting of Baile da Gaiola — and was initially acquitted of the charges, but after an appeal by the Public Prosecutor’s Office in Rio de Janeiro, da Penha was convicted and sentenced to six years and eight months in prison. Part of the evidence against him was based on videos and photographs: of him in the company of people accused or convicted of drug trafficking, or mourning the death of acquaintances in police operations. Rennan’s defence argued that to live in the favela is to be close to violence. Growing up and living alongside criminals, and maintaining a cordial relationship with them, is a survival tactic.

After the Brazilian Bar Association criticised his arrest and conviction, claiming that it was an attempt to criminalise funk, and a series of appeals to the Supreme Court, in November 2019, da Penha was released from prison after obtaining a habeas corpus from the Supreme Court.

SÃO PAULO FUNK

For many, local culture for favela youth is dwindling. MC Leonardo, one of the main funkeiros during the ’90s, lives in Rocinha, the largest favela in Rio de Janeiro. “We used to have many options for entertainment near home,” he remembers. “Nowadays, we have information, everyone has the internet, but we don’t have options. When I was 20 years old, I knew more than 20 favelas. Today, with the ban on bailes, the favelas no longer know the favelas.” Renato Martins, music researcher and creator of the label Funk na Caixa, explains that funk in Rio de Janeiro didn’t stop being produced — but it did enter a crisis period. “Usually, a musical movement lasts five to eight years,” he explains. “In the ’90s, the guys from rap came, then bands and singers such as Bonde do Tigrão [and] Tati Quebra Barraco, after the ‘corridor’ dances. Between 2005 and 2007, Rio started to lose space. There were some successes, but [only] a few — nothing that would bring artists capable of sustaining an entire movement.”

In São Paulo, the internet transformed the way funk was produced and consumed, and a new generation found more ways to profit from the music. “At the beginning of the decade, YouTube paid a lot of money for visualisations, but in Rio, they still depended on regional funk distribution through sites or exchange of material,” Martins explains. “The São Paulo generation came with YouTube paying a lot for views, and some videos had millions of them.”

KondZilla is a production company that makes videos and promotes funk in Brazil. They have 57 million subscribers and are among the top 10 YouTube channels globally. Some of their self-hosted videos have more than 90 million views. GR6, another production company, has almost 30 million YouTube subscribers, and is also another heavyweight in the São Paulo funk market. “Rio de Janeiro is creative, but it’s very oba-oba (too much partying),” says DJ Marlboro. “It has no professional structure. It doesn’t think ahead and isn’t organised. In São Paulo, funk [became] professional, and a new business behaviour was fundamental to creating the industry.”

As São Paulo’s funk is right on the edge of the city, in remote suburbs, KondZilla has helped to break the barrier in São Paulo between the elite and the poor, with funk gradually being played at middle class parties in the city. But just as in Rio de Janeiro, funk is criminalised in São Paulo, with bailes being violently repressed by the police. (Baile da Dz7, the street party in the Paraisópolis favela that faced the violent crackdown in which nine people died, is the largest baile in the city.)

São Paulo’s funk grew initially between 2011 and 2014, when a sub-genre arrived called ostentação (ostentation) — with funkeiros parading with imported cars, jewelry and expensive clothing. The style combined with the country’s breakthrough moment of accelerated economic growth until “it started to get a bit false”, says Martins, when the country began to face serious economic problems.

Martins believes that São Paulo began to face a problem that made it difficult to push its native music. “Those who were already consecrated [in the scene] did not make space for the new, and the new needed more resources to enter the market, so the new plastered the market,” he says. “The hangover from the funk of São Paolo allowed for a new movement, called 150bpm: an accelerated take on the sound that’s made Rio de Janeiro relevant in the world of funk again.”

Rennan da Penha, DJ Polyvox and DJ Iasmin Turbininha were early figureheads for this sound. Turbininha, one of the first female funk DJs, was born and raised on the hillside favela of Mangueira, in Rio de Janeiro. “With funk, many people in the community have opportunities,” she explains. “Funk has taught me to think, to reach places I never imagined. Funk is an inspiration for those that live in communities, to have opportunities, to learn.”

But she’s also had to battle sexism and prejudice to maintain her career. “Being the first woman to play at a community dance was very important. I went to places I never thought of playing,” she explains. Although the threat of police violence and criminalisation remains, the prejudice she faced often came from inside the funk scene.

“Playboy DJs, famous DJs, think everything that comes from the favela is great,” she says, “but if it’s a Black guy or women from the favela going up on stage and playing the same songs, they don’t respect us, they have prejudice. It’s hard to have hope when you live in the favela, to wake up every day to face a stray bullet, the fact that people that you know are dying,” she says. But, like DJ Marlboro says, “funk is the union”.

THE FUTURE

Funk has continued to reinvent itself, and online platforms like KondZilla and GR6 have helped to professionalise the scene in the last decade; launching the success of funkeiros such as MC Guimê, Kevinho and MC Gui, who have outgrown local audiences and found nationwide and international success. Nowadays, it’s not rare to see funk MCs on national TV shows. But it’s hard to balance the international growth and exposure of funk artists alongside the continued criminalisation of where funk comes from. For Professor Palombini, it remains the most critical concern facing the genre today.

“The criminalisation of funk is lethal to the person in the favela, but his culture survives [by being] sucked from the periphery towards the centre [and into the cities],” says Professor Palombini. “With artists from Brazil and other countries adopting the sound and promoting it, funk seems less subject to stray bullets that seek their targets in the informal economy of the favela. But the favela itself continues to fight for rights and recognition.”