Dance music is in a mental health crisis

Dance music has a mental health problem. Sirin Kale speaks to artists such as Luciano, Courtesy and Marie Davidson, as well as some PRs and promoters, about one of the principal issues affecting our scene, and the potential solutions to this pressing problem

March 2017. Luciano, real name Lucien Nicolet, is in Frankfurt airport, and he’s bent double with heart palpitations. He knows something isn’t right: things are very wrong, in fact, but he tells himself that everything will be okay. Soon after, he’s hospitalised with an overdose, induced by five days of touring and partying.The Swiss-Chilean techno DJ has been abusing his body for decades. He knew this day would come, but he’s still in denial.

“I was trying to convince myself that it wasn’t happening,” Luciano remembers, two years on. After being discharged from hospital, it hasn’t sunk in. “The next weekend, I’m taking drugs and drinking alcohol.” After another late night, one of so many late nights throughout his career, Luciano has finally had enough. He goes back to his hotel room, turns on his laptop, and starts searching for rehabilitation centres. “My whole life hit the bottom,” he says. “I didn’t feel like I could speak about it with my family, and I felt like there was no cure, no way out. I decided to try rehab so I could say that I sought professional help, one last time, before dying. I’d tried detoxing before, many times, and it never worked. I knew that I had a beautiful, incredible life, but there was something deep inside me that was triggering me. I was ready to kill myself. It was a slow suicide. I truly thought I’d go [to rehab], detox, and then after a few weeks, go to my grave.”

Only, it didn’t go like that. Luciano went to the Dara Rehab Centre, in Koh Chang, Thailand. It was hard, harder than he expected — but it worked. Now, Luciano is sober, and has rediscovered his love for music. He decided to speak out about his struggles with addiction (including on a high-profile panel at this year’s IMS) because his friend Avicii — real name Tim Bergling — wasn’t so lucky.

“Tim used to come and hang out at my parties,” he says. “I always admired him... he was just a young guy, gentle and sweet.” Luciano got to thinking about all the other young people who might be struggling in the industry, too. “I realised that I have a higher responsibility towards dance music, and to creating a healthier environment — because dancing is good, dancing is healthy.” Once again, he fired up his laptop. This time, he was going public with his story, in the hope of helping others. In May 2018, Luciano logged into Facebook, and began to write: “Today I am one year old; my rebirth day... I decided to stop suffering in silence.”

“I’m up to 25 people in the music industry now who have taken their lives, whether they’re close friends or one step removed. I’ve been seeing this situation grow, and the reality is that it’s going to keep happening. The scary thing is that people can be chatting with you one day, and they can seem fine — and the next minute, they’re not.” - Ben Turner

The problem

Dance music has a mental health problem. It’s a statement of fact; unambiguously correct. People are dying: Bergling last year, Keith Flint of The Prodigy this year. They’re the deaths you see reported in the press, but there are also the people you never hear about — the people behind the scenes, the ones who do the soundcheck, book the acts, or sort your rider.

“I’m up to 25 people in the music industry now who have taken their lives, whether they’re close friends or one step removed,” says Ben Turner, music manager and co-founder of dance music health and wellness retreat, Remedy State. “I’ve been seeing this situation grow, and the reality is that it’s going to keep happening. The scary thing is that people can be chatting with you one day, and they can seem fine — and the next minute, they’re not.”

A lot has been written about the perfect storm of factors which make dance music a particularly toxic industry for anyone struggling with their mental health. Relentless touring schedules; jetlag; 6am flights and 4am set times. Anonymous hotel rooms that blur together. The pressures to appear successful on social media. There are financial pressures, too. The industry is contracting — in part because many young people have become health-conscious, favouring Instagrammable daytime pursuits over the clammy environs of nightclubs — which means that it’s harder to make money, and everyone is struggling to keep their heads above water. And that’s leaving aside the corrosive impact of drug and alcohol addiction, which are, let’s face it, ever-present in the industry.

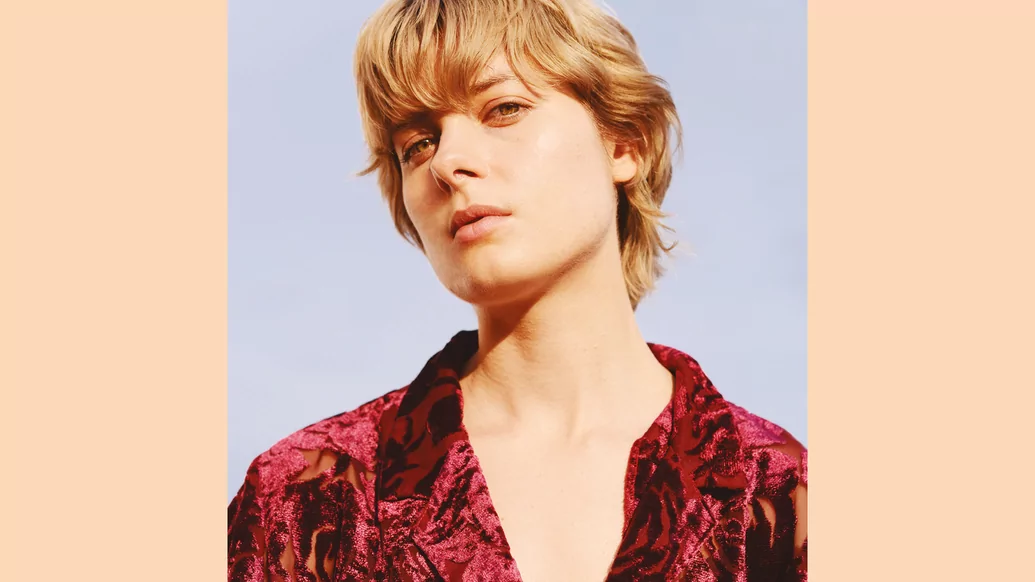

“If you want to talk about the structural things that are difficult about being a touring artist, then it is really basic things that would affect anyone’s mental and physical health,” says Danish techno artist, Courtesy. She references irregular sleeping, constant time-zone changes, and non-stop touring as things that take a toll on her mental well-being.

“I have had experiences where a promoter is giving me shit for not partying. Honestly, what kind of service do you think I’m giving you? I’m not selling my company. I’m there to perform for people, and that’s what people pay me to do.” - Courtesy

But it’s not just the heavy lifting of being a touring artist. It’s also the emotional strain, one that comes with being a figure in the public eye. “Something that I have struggled with in the past is some promoters’ expectations of your availability around DJ sets,” says Courtesy. “For me, the performance aspect of my job is what I love — those two hours I get to spend in front of people, playing my favourite music and having this connection with the audience.”

The other stuff — the schmoozing, the pre-set dinners, or the post-set partying — can feel like hard work. “I have had experiences where a promoter is giving me shit for not partying,” she says. “It’ll be like, ‘Well, the next time I book you, you’re going to stay afterwards so we can party together’. And honestly, what kind of service do you think I’m giving you? I’m not selling my company. I’m there to perform for people, and that’s what people pay me to do. So that’s something that can add extra stress.”

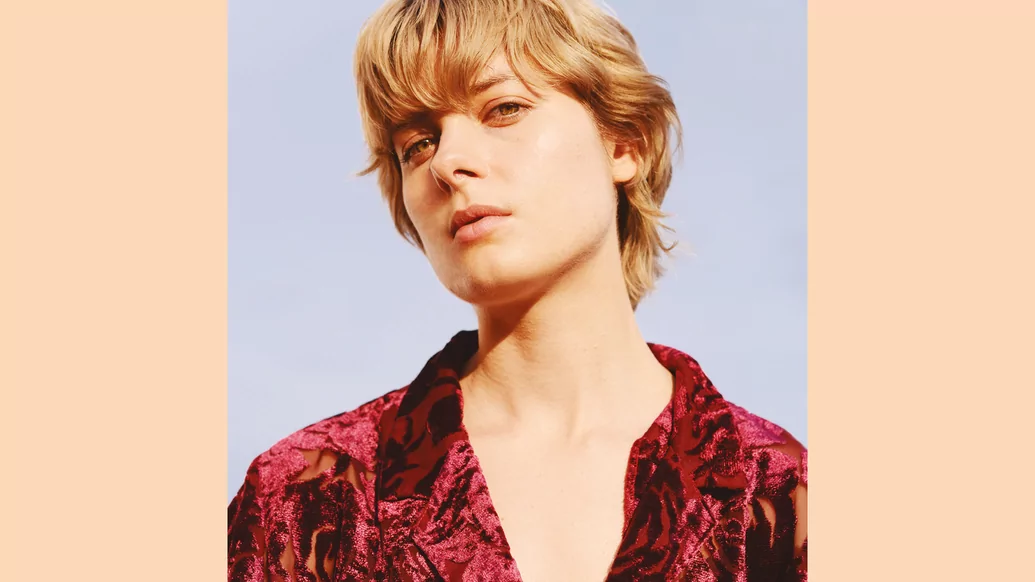

The worst thing artists can do is lose sight of what they’re there to do: they’re there to work. This is a job. But when your office is a nightclub and your colleagues are often drugged-up strangers, it’s easy to forget what brought you there. Add in the international travel, loneliness and isolation, and things can quickly spiral. “The infrastructure around electronic music, it’s all about the party,” says French-Canadian musician and vocalist Marie Davidson, “and that for me is the problem.” There have been times where Davidson has lost herself in the party, and regretted it afterwards. “There are the people having a good time, but you’re not one of them. And if you make that mistake, if you forget that and become one of them for a minute, then you really are on your own. Good luck figuring out how you’re going to get back to your hotel.”

All the artists DJ Mag spoke with for this article had similar stories of finding themselves broken and alone, after an exhausting and isolating schedule of non-stop work. For Davidson, the moment she realised she had to prioritise her wellbeing happened in Utrecht. She’d played three gigs back to back: travelling from her home in Berlin to London, then to Moscow for another performance, and finally to Utrecht for one last set.

“When I got to my hotel after the Utrecht gig, I was really questioning my mental stability. I basically hadn’t slept since Moscow,” she says. “I broke down. You start to doubt your own reality, what’s real and what’s not. When you don’t sleep for so long — and when you party, on top of that — you’re so chemically imbalanced inside. It’s really hard to keep that up.”

Beyond the booth

It’s not just DJs and live performers who are struggling. For every artist basking in the adulation of a sweaty, euphoric crowd, there are the people behind the scenes, making it all possible. They too might be struggling with their mental health, but their stories are rarely told. If we’re going to focus on the mental wellbeing of those within dance music, that means moving out of the DJ booth and into the wider community.

When it comes to the panel events or awareness-raising campaigns around dance music and mental health, the people on the back end of things — PRs, promoters, managers or agents — aren’t ever talked about. “We don’t tend to have those conversations [about mental health] from our point of view,” says Owen Bloodworth, of UK dance music PR specialists The Rest Is Noise. “I guess it’s not press-worthy. We don’t care about the PR having mental health issues from the stress of their job, because why would we? Whereas with artists, it’s high profile — and that’s what people want to read about.”

Bloodworth lists some of the stresses he encounters in his job: the pressure to perform to deadlines, and get artists and events to where they need to be. “You need to constantly be producing pieces of journalism, features, articles and news announcements, and that’s reliant on whether media platforms want to post them in the first place. You also need to be reporting back to the client all the time. And to the client, the event is their baby — that’s their world, so it can be hard to communicate to them that some people might not have the same belief in their event.”

Much of Bloodworth’s work takes place on festival sites, which comes with its own set of challenges: he feels that he can’t ever switch off and enjoy the festival, because he has to be watchful for anything that may go wrong. (Luckily, the worst thing that’s ever happened in his career is a stage blowing away.)

“You’re walking around a festival,” he says, “and you know that there could be a death or serious injury, anything could go wrong, and you’re the barrier between the press and the festival organisers. You’re the first person the press will come to if anything happens.” It’s a stressful job, and without the salary top-tier touring artists can command. Bloodworth doesn’t feel like he’d ever be able to open up about how he’s feeling, because he’s worried it would be seen as unprofessional. “No matter how I’m feeling, you have to put on a sunny demeanour, because you’re still selling the festival to a certain degree. The sad thing is that I’ve accepted that anxiety is the nature of the job.”

“There’s a pressure to appear positive. If you complain about it, people say, ‘Try working in insurance!’” - Simon Denby

As the industry goes through a period of flux, the pressures can be compounded. “The music industry at the moment is struggling,” Bloodworth says. “Events are getting harder to sell out, and the market is getting more diluted. Artists are struggling to sell records. I struggle because there are so many events at the moment, so I’m fighting to get my event heard about. I think we’re going to reach a breaking point. Change needs to be across the industry, rather than just looking at the top level.” He pauses. “Because there are pressures at every single level.”

Promoter Simon Denby, of the record label and party crew Percolate, knows the pressures that Bloodworth speaks of up close. He talks about the rise of 24/7 workplace culture having a deleterious impact on his mental health. “Whether you’re a promoter, artist or manager, you’re never really off — which can be difficult.” The emotional cost of performing such public-facing roles can be immense. Sure, the average person on the street might say that throwing parties, or representing festivals for a living, is a dream job. But as anyone who’s ever had to work at 10 or even 12 festivals in one summer knows, it’s not always as rosy as you might think on the inside. “There’s a pressure to appear positive,” says Denby. “If you complain about it, people say, ‘Try working in insurance!’”

Personal solutions

Everyone DJ Mag spoke with was in agreement on one thing: it doesn’t have to be this way. Dance music can change. But how? For artists, it’s often about setting boundaries in their professional lives, particularly when it comes to extreme workloads. As an artist, “it’s about having faith in your booking agency,” says Courtesy. “You can mix it and say, ‘I’ll do one long tour a year, and the rest of the year I do three weekends, or eight gigs a month’.” She’d like to see that become common practice on an industry level. “The booking agent works for the artist. I think a lot of artists don’t realise they can set the agenda... [that they can] sit down and have a conversation with everyone they work with about what are reasonable expectations for them, and how they want to tour.”

A common adjustment many artists make to prioritise their wellbeing on the road is one and the same: sobriety. Within two years of touring, Courtesy “completely stopped drinking,” she says. “It was impossible for me to maintain my mental health if I didn’t.” When you’ve used alcohol throughout your career, stopping can be like losing an old friend — albeit a friend who is flakey, cancels all the time, and never has your best interests at heart. “I had to re-learn how to DJ without drinking, because it was also a way of treating my anxiety.”

She wasn’t alone in self-medicating with alcohol: before his death, in the 2017 documentary Avicii: True Stories, Bergling talked candidly about how the pressures of touring led him to abuse alcohol, as a way of coping with his underlying anxiety. “There was never an end to the shows, even when I hit a wall,” Bergling said on camera. “My life is all about stress.” His alcohol abuse led to an initial diagnosis of acute pancreatitis while on tour in 2014.

Davidson also tries to stay sober on the road. It’s tough resisting drugs and alcohol when you’re surrounded by people who indulge. “Just being in a place where people are always intoxicated makes me want to do it also,” she says, “or it makes me disassociate and feel really far away from them, and lonely. But that’s okay — because I have my life, and I don’t need to feel like I’m part of the party.”

Learning to say no to situations that will cause you stress also helps. Courtesy swerves pre-set dinners as a rule, preferring to recharge in her hotel room before she plays. “You can be warm and polite and not go to the dinner,” she says. “The reason I don’t do dinner is because I’m saving my energy for the set. If there’s any promoter who saw me and felt like I didn’t fully give myself to those hours of performing, that’s a different story, but I don’t think anyone could say that. Because I go in, and bring my energy.”

It’s not only those working in the industry who are increasingly choosing sobriety — it’s the punters, too. Thirty-five-year-old Michael Joseph Ianni is a publicist and long-time dance music aficionado from Toronto. He decided to go sober three and a half years ago, after he realised his party lifestyle was killing him. He’d started raving aged 14, but the sense of acceptance and community Ianni found in those initial, halcyon days dissipated with time. He’d show up to work drunk, still smelling of alcohol, or get kicked out of clubs. “My reputation got ugly,” he says frankly. “I pissed off a lot of people.”

Since getting sober, Ianni’s experience of clubbing has changed dramatically. “It was magical,” he says. “Being sober gives you more time and energy to enjoy the things you set out for. I’m not a prisoner of the intense highs and lows that drugs facilitate.” He recently attended Canadian festival Bass Coast, and also raves about being at Bestival without taking narcotics. But it’s not always easy to be a recovering addict in spaces that prioritise hedonism. “Being at a festival can feel lonely, especially if your friends are using drugs,” he says. “Your mind starts to perform inventive gymnastics: you think, ‘Maybe the problem was just booze and coke... I could just microdose some MDMA, or acid?’”

Structural solutions

Too often, we’re told the following about mental health: speak out. Open up. Let someone know how you’re feeling. It’s all well-intentioned guidance, sure, but conversations alone won’t improve the situation for those working in dance music. Only on-the-ground, systematic, structural changes will. When it comes to mental health, dance music is a sinking ship. We all need to get down into the bowels of the vessel, roll up our sleeves, and plug the leak — for good.

Expecting individuals to do the mental hard labour required to exist within a broken system is arbitrary and unfair, explains mindfulness expert Professor Ronald Purser of San Francisco State University. Instead, we need to engage in “civil mindfulness” he says. “A civil-oriented mindfulness goes beyond individualistic stress reduction, behavioural self-management, and self-care coping tools.”

“A civil-oriented mindfulness goes beyond individualistic stress reduction, behavioural self-management, and self-care coping tools.”” - Professor Ronald Purser

In his view, consumer-driven approaches to mindfulness — what he terms “McMindfulness” — risk appropriating the language around mental health and selling it back to consumers for profit. It’s what we’ve seen with the pinkwashing of Pride festivals: taking what was once a radical, anti-capitalist ethos, diluting it, and selling it back to consumers for profit. (Arguably, expensive DJ retreats like the forthcoming five-day Orbit package, designed to help DJs de-stress — at a cost of €1999 — represent this capitalist impulse.)

Instead of these profit-driven initiatives, Purser suggests grassroots organising as a way for those within dance music to improve their working conditions. “There used to be musicians’ unions that provided job security, wage standards, and protections for working conditions,” he says. “Most musicians don’t have these protections. They are on their own to fend for themselves — in a neoliberal system that thrives on competition and narratives of self-responsibility.” By forming collectives or even informal advocacy groups, artists and industry workers can “engage in dialogue and reflection on how their mental wellbeing is embedded in the social and economic conditions of the industry”. It’s a trend we’ve already seen established with dance music collectives like Discwoman and Siren, but rolling it out on a wider level could help more people across the industry.

In essence, we need to shift the focus away from individuals to deal with the anxieties their jobs induce, to look at the reasons why they’re feeling stressed at the job. Are unreasonable expectations being put upon them? Do we need a cultural shift to minimise the onerous obligations currently placed upon many people within dance music — from the expectation that PRs should always be upbeat, to the view that artists aren’t good sports if they don’t socialise with the promoters after their performance? Absolutely. But the truth is, individual promoters, DJs, booking agents and managers can’t be expected to fix the problem on their own. Just like how a party is the sum of its parts — the crowd, the vibe, the music, the atmosphere — so too can we only fix dance music’s mental health problem through collective action. We need to pull together to root out the collective rot in the industry, because no one person can do it alone.

The pioneers

Significant steps are being taken to achieve system-level changes within dance music. Denby was at Amsterdam Dance Event in 2016 when he started chatting about mental health with Jim O’Regan, a booking agent who works with artists including Ben UFO and Denis Sulta. They decided to throw a fundraiser for UK mental health charity Mind the following January. After raising over £10,000 for Mind, Denby, O’Regan and mutual colleagues wondered if there wasn’t more they could do at a structural level. In collaboration with Mind, Denby’s been working on a handbook and training programme designed to promote better mental health at all levels within the industry. The Association For Electronic Music (AFEM) has also produced a guide to mental health in association with the Music Managers Forum, Help Musicians UK and Music Support.

“A big problem with electronic music is that there are a lot of smaller companies, and they don’t have HR training in how to deal with issues,” Denby says. “We’ve been working on this [handbook] for the last four years, and it was so apparent back then that there was a massive issue not being talked about. You see friends having to leave the industry or take long breaks because of stress.” The handbook and training programme will be published online later this year, and Denby has high hopes for what it might achieve.

Dance music wellness retreat Remedy State has recently been renamed ARETÉ, and is held in Ibiza annually to coincide with influential music summit IMS. Now entering its third year, it provides a space for industry professionals to come together and workshop structural solutions to the existential challenges facing the industry — at an affordable cost (packages start from €300). “People can only achieve their full creativity and potential if they’re in a good state of health and mind,” says Turner. “We approach this topic in a positive way, to help pull people from dark corners into a place of creativity.” He’s passionate about creating best practice guidance for those working in the industry. “There is no time,” Turner adds. “We’re losing people of all levels of skill and experience through mental health issues.”

It’s not just about safeguarding artists and industry professionals, of course. Real change broadens out the conversation to include consumers. Ianni lists what is needed to make music festivals more inclusive for sober people: non-alcoholic beverages on tap, daytime activities like yoga or art installations, safe spaces for sober people to have daily meet-ups, and harm reduction teams on site, with large visible presences.

“I find that a lot of festivals are implementing more wellness areas, and older DJs are practicing — or even teaching — yoga and meditation,” says Turner. “When festivals make room for more activities, it makes attending festivals sober easier.” It’s worth pointing out that many clubs are reliant on alcohol sales to turn a profit, so sober clubbers aren’t exactly the demographic they’re after. However, sober-friendly parties like early morning rave collective Morning Gloryville, or Scottish teetotal club-night Sober Sonic Events, are popping up across the country. Outside of a festival environment, making the regular club experience more accessible for sober ravers would be a help.

Another thing that might make a difference would be the presence of mental health first aiders in clubs and festivals: professionals that are trained to spot the signs and symptoms of common mental health issues, listen non-judgmentally, have supportive conversations and sign-post people to further support. Mental health first aiders are already in operation at some UK festivals, including Pride and UK Black Pride, although they’re not yet a fixture in our club scene. Vicki Cockman of Mental Health First Aid England hopes that, one day, they’ll be as ubiquitous as a cloakroom attendant or a bouncer. “We are working towards a future where anyone experiencing mental health issues, whether they are at a festival, in a nightclub or any other kind of event, can access timely and appropriate support,” she says. “Just as you would expect with physical first aid.”

The future

There’s no doubt that things are changing at a structural level, thanks to the dedicated efforts of innovators. What we’re heading towards is a sort of sea-change in an industry that has, for too long, relied on powders and alcohol to paper over the cracks. It doesn’t have to be this way. We can all co-exist in an industry that we were drawn to for the love of the music, not because we’re seeking oblivion. At least, that’s what Luciano believes.

“That’s what I’m trying to make everybody understand,” he says. “They’re all like, ‘How can you do your job, how can you go out?’ I’m like, ‘I’m having more fun than anybody else! I go out — when the music’s good, I dance, when the music’s not, I go home...’ I want to let the new generation know that it’s ok. You don’t have to stop going out if you stop drugs. This is complete bullshit. It’s going to be harder, but if you really love music and dancing, there’s no reason why you should stop going out. It’s not like I became a monk or anything like that.”

The fact that Luciano is evangelical about spreading the gospel of clean-living makes sense: he’s been given a second chance at life. Our goal as an industry must now be to ensure he’s not the only one.