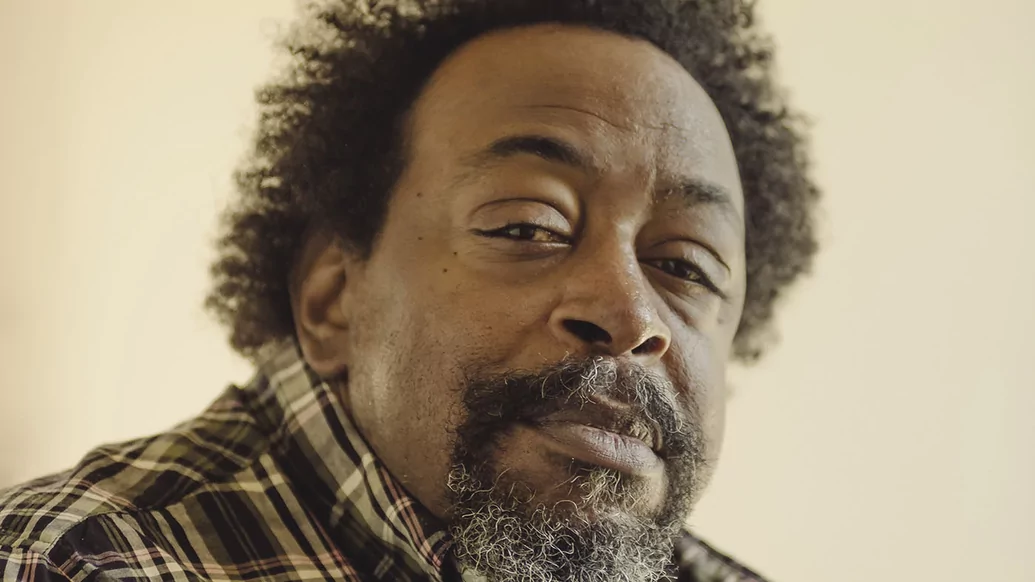

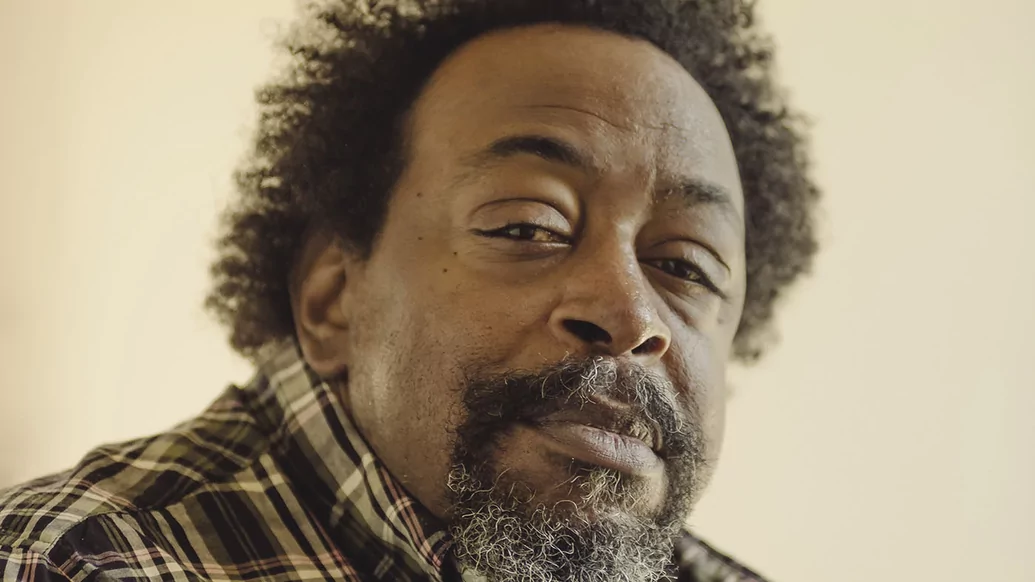

Dax Pierson's queer divine dissatisfaction

After a devastating accident, musician Dax Pierson spent years rehabilitating himself, and working towards a hyper-personal sound. With his latest album, ‘Nerve Bumps (A Queer Divine Dissatisfaction)’, he details new ways of living and making music as a queer, Black, disabled artist through vivid, experimental electronics

Deep in the manzanita-studded woodlands of Northern California, there’s a scenic resort where gold miners once bathed in restorative mineral springs, and queer hippies sought spiritual refuge amid the trauma of AIDS. It’s also the location of a scrappy music festival. Gays Hate Techno, a music collective whose name is firmly tongue-in-cheek, took over the resort’s clutch of frontier-era buildings for an extended weekend in 2016, to showcase emerging performers from the San Francisco Bay Area’s trans, queer, and non-binary community.

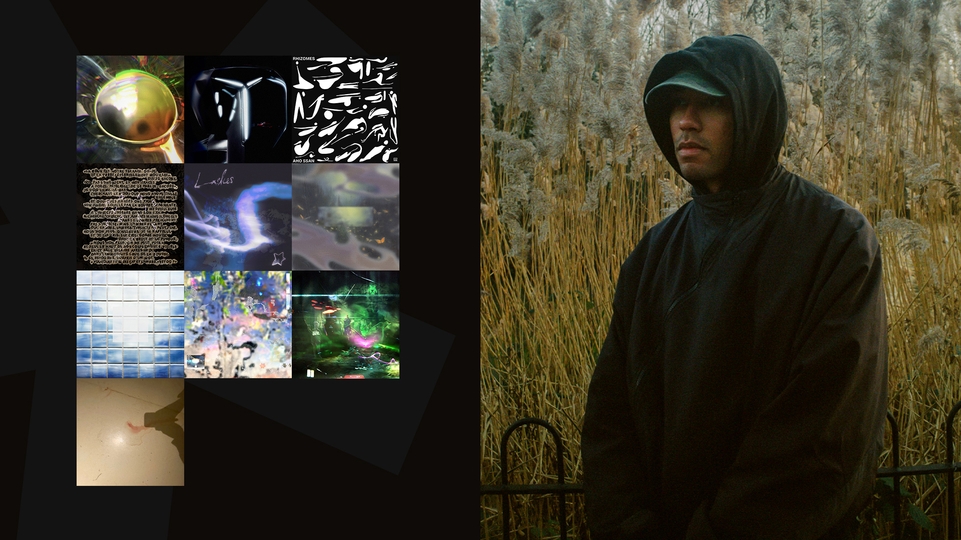

As the May moon shone down on the property’s central Heart Lodge, next to the “ambient yurt”, the crowd hushed when one of the festival’s main attractions approached the performing circle. Oakland artist Dax Pierson positioned himself before a small table, the whirr of his motorised wheelchair floating atop the space’s buzzing speakers and rigged-up purple lights.

Equipped with a simple set-up of iPads and other touch screens, Pierson, who is paralysed from the chest down and unable to use his fingers, soon filled the barn-like structure with warbling ostinatos, swooping drones, mercurial percussion and, crucially, samples of his doctors’ prognoses and his own daily medical realities, including the sound of his power chair.

Gays Hate Techno brought together many diverse strains of queer Bay Area electronic expression: Oakland venue LCM’s experimental noise scene, the underground family of Ghost Ship, Katabatik’s mountaintop acid-industrial campouts, Club Chai’s pan-cultural genre-fluidity, the historical legacies of composer Pauline Oliveros’ “deep listening” practice, and Lou Harrison’s oddball handmade instruments.

But despite being immersed in the scene and its history, Pierson seemed like something completely new: a queer, Black, disabled person making live electronic music about their life, using elements directly from it; expanding from the very particular to the strikingly universal.

“It was a big moment for me,” the candid and funny Pierson says over Zoom from his home, where he’s recovering from a year of battling serious health issues; undergoing a gruelling regimen of dialysis, medication, and therapy while bedridden. “The festival was ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act] accessible, and the collective made space for me to be there. I didn’t know how my music would translate in that setting, but I realised that people enjoyed my work. I’ve spent years researching and developing what kind of music and career is possible for me, so being invited gave me something to work towards. It gave me confidence.”

Pierson’s poignant new studio album ‘Nerve Bumps (A Queer Divine Dissatisfaction)’, his first as an electronic musician, expands on themes that appeared on his improvisatory 2019 compilation, ‘Live in Oakland’. It’s been 16 years in the making, its roots tracing back to the tragic accident that cost Pierson his mobility. Both albums, released by Oakland’s Ratskin Records label, are grounded in the physicality of Pierson’s existence, often quite literally.

Whereas ‘Live in Oakland’ incorporated extended vocal samples — his doctor’s gentle but dire explication of his surgical options, a chopped-and-screwed loop of Pierson intoning “Don’t take your physical abilities for granted, you could lose them at the snap of a neck” — on ‘Nerve Bumps’, Pierson engages in a more impressionistic, yet still intensely personal style.

Opener ‘Adhesion’, a headlong cyber-tunnel race in 7/8 time, refers to the term his massage therapist uses for the knots in Pierson’s muscles. ‘Keflex’, which runs together vintage “game over” sound effects and a warped Cocteau Twins sample, is named for an antibiotic given to people with spinal cord injuries to fight against bladder infection, a common ailment from ever-present catheter tubes. The trip-hop inflected ‘I Slay The Pain’ skitters and bleeps to a vocal, thumping victory. Track lengths vary widely, signalling a certain precariousness — of attention span, of mortality, of security under the United States’ healthcare system —although all are deeply felt and intricately constructed.

A glossy photo of Pierson’s Permobil F5 Corpus VS wheelchair by Leonardo Gonzalez covers the back of the ‘Nerve Bumps’ vinyl sleeve, a representation of Pierson’s identity; he felt it was essential to let the disability community know he was one of them. And the album title itself directly summons Pierson’s condition. “When my body was adjusting to being paralysed, there was a lot of random muscular activity,” he says. “Spasms would fire off in my legs and I would get goosebumps. One time I accidentally said ‘nerve bumps’ and it became a little joke between my partner and I.

“And maybe it’s a play on ‘bumping’ as well,” Pierson jokes. “As in, if something’s going hard, it’s bumping, it’s banging. These tracks are all bangers from a spinal cord injury point of view.”

Pierson’s rapid-fire collage techniques and roiling production style ensure that his rush of ideas also includes tenderness and humour. The album’s final track, ‘NTHNG FKS U HRDR THN TM’ — a sinuous, 11-minute synth wormhole that dissolves into a tolling bell — could be a comment on the wisdom and melancholy of growing older as a gay man.

“I took the title from a line in Game Of Thrones as filtered through millennial text-speak,” he says. “When I heard the character Ser Davos say that on the show, I was like, ‘Yes, that’s church! Amen!’ Everyone can relate to that. My 80-year-old father was the first to recognise the source.”

The flipside of the album’s physicality is a spiritual and creative restlessness, captured by its subtitle: “No artist is pleased... There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others,” a guiding quote from dance legend Martha Graham. It’s a mantra Pierson and his partner Chuck Nanney, whose painting graces the front of ‘Nerve Bumps’, often intoned during Pierson’s making of the album. It can be read as a deliciously haughty admonition to get over any drama queen moments, and just keep keeping on.

“There were a lot of times working on this album when I didn’t quite feel confident about what I was doing, or was uninspired — and I would look into my past or toward other genres for some way forward,” Pierson says. “I feel this album was produced more as an indie or hip-hop album, because I was reaching out for so many different things.

Working on electronic music can feel very solitary,” he continues, “and there’s an urge for perfection as well as connection. You’re moving around all these ideas that you have, without being able to bounce them off other people, as in a band. It can be maddening.“

Pierson’s journey to becoming an electronic musician was a long one. He first came to prominence in the early 2000s with his band Subtle, an avant-garde hip-hop sextet closely associated with the sprawling Anticon collective, which spliced together free jazz and post-rock signifiers into anxious, rap-driven soundscapes. Pierson played keyboards and harmonica, as well as singing and beatboxing; Subtle released several records and toured the United States. He was the only openly queer member of the close-knit alternative rap scene, but its embrace of outcasts and experimentalists made him feel supported.

In 2005, Subtle’s tour van hit a patch of black ice in Iowa and flipped over. Although his bandmates sustained only minor injuries, Pierson’s seat was improperly secured, and he was flung against the ceiling. The impact fractured his spine, paralysing him. It was a devastating injury, but somehow he got through it — a video taken soon afterwards of Pierson in rehab shows him mugging for the camera, and features a light-hearted, ‘Rocky’-like montage of him training with his physical therapists. Subtle released records to raise funds for his recovery, and he even appeared on the band’s final album in 2008, using Ableton for the first time.

He eventually won a lawsuit against Ford, which manufactured the van, and was awarded $18.3 million in damages. But now that he could no longer play traditional instruments, he had to reimagine his life as a musician. What followed was years of self-training on improvised equipment, experimenting with everything from custom midi controllers and personalised programs to “wrist attachments where I was trying to ‘play’ a keyboard. I tried a lot of things, and didn’t really get much outside help. I was figuring things out on my own,” he said.

A true breakthrough came with the availability of touch screens, which Pierson could more easily manipulate by dragging his hand across them. (“Nowadays, live performance is like 50% DJing”, he has said. “I’m still sliding faders up, after all.”) The second half of ‘Live in Oakland’ — recorded in 2018, four years after the first half — was the manifestation of this newfound technical freedom. “That was my first performance using only an iPad and an iPhone,” Pierson says. “I did not use Ableton, I did not use a computer. I was only using iOS equipment, which I felt really rad about.

“You know, this generation is using vintage equipment from my youth, and spending thousands of dollars on modular synthesisers,” he continues, “and here I am, like, ‘What can I do with a $300 iPad and a generation-old iPhone?’ That was my nod to the vintage craze. I respect and love the music people are making with older equipment, but you don’t need a table full of hardware. You can make music with whatever’s at hand. The iPhone is a wonderfully expressive folk instrument. Just open an app and start making noise. If you happen to be recording at the time, you can always go back and chop that shit up.”

Although he accepted that his most viable musical direction was electronic, Pierson originally had some reservations. “In a way, it’s funny that I’m doing this at all,” he says. “I had really never gone to a dance club. I have an alternative rock history. I didn’t get my first computer until a year before the accident.”

Despite his protests, Pierson has a keen knowledge of electronic music. He worked for a decade as a clerk at record store Amoeba Music before forming Subtle, which was inspired by his favourite bands Tortoise and Can. When asked about influences in his vocal sampling work, he mentions Steve Reich’s 1966 ‘Come Out’, John Oswald’s Plunderphonics and Vicki Bennet’s People Like Us projects, Brian Eno and David Byrne’s ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’, and Bay Area musicians Wobbly, Matmos and Negativland.

“Even now, I don’t consider what I do to be techno,” he says. “I consider myself an experimental electronic musician. But my perspective of techno over the years has changed. A lot of the music I made was to challenge what I thought of techno, as purely dance music, or body movement music. But techno can be a very expressive and even inclusive form. I think a lot of that is becoming more pronounced, the more different kinds of people I see doing it. The people making electronic music at Oakland venues and recording with Ratskin, we were all the weirdoes and freaks. They embraced me, just as the alternative scene had.”

That supportive community was rent by tragedy in 2016, when a fire at underground Oakland venue Ghost Ship claimed 36 lives, many of them friends and acquaintances. Pierson wrote ‘For The Angels’ in their memory. On his ‘Live’ album, the track is a cavernous, acid-tinged voyage, ending with a hands-up synth line summoning spirits back to the dancefloor. It came to him in a rush of inspiration, written about 24 hours before his performance. On ‘Nerve Bumps’, ‘For The Angels’ is transformed — another wrestling with queer divine dissatisfaction — into a stately, strings-drenched processional around the sun. The newer version perhaps reflects the community’s grieving process, a commemoration and a form of letting go.

“I kept vacillating between the words ‘angels’ and ‘ancestors’, as they both sounded right for the title of the piece,” Pierson says. “I wanted to make a tribute to the victims. The music gives me the feeling of euphoria and joy. But I also feel that there’s nostalgia, and may be a little darkness. After my first performance of it, I wanted to add more voices beyond the standard techno voices in the original, more meticulous editing. I was thinking about the advent of techno and how it has evolved and morphed into other subgenres, while still remaining relevant.”

As a survivor who struggles to hold his head up daily due to pain, Pierson finds catharsis in this type of constant shifting and transfiguration, remaking his music even when confined to his bed. He’s currently working on a new live show and relishing the freedom that online tools like Zoom and Twitch have afforded people with mobility and health challenges to perform around the world. “I hope that doesn’t go away after COVID-19,” he said. He’s also heartened by the gradual heightening in visibility of people like himself.

“I think it’s an amazing time for queer, Black electronic musicians right now,” he says. “I’m seeing so much coverage out there of incredible artists, where I’m like, ‘Where were all these people in the 2000s?’ We had Black, queer techno forebears in the ’90s, in Detroit and Chicago, but it seems that once it got filtered through a European sensibility that somehow got lost. So this is a real period of global discovery — actually, of catching up, because you know, we’ve been here all along.”