The ecstasy despite the agony: photographing gay clubbing in ‘90s northern England

Photographer Stuart Linden Rhodes, known mononymously Linden, spent the ‘90s capturing the queer clubbing scene in the north of England on his camera. Now his work is being memorialised in an upcoming book, Out & About With Linden. Simon Doherty speaks to Rhodes about his works, which depict an abundance of unmitigated queer joy in an era of political oppression

Throughout the 1990s, Stuart Linden Rhodes was a teacher by day and a writer and photographer covering the north’s gay clubbing scene at night. In the classroom he was known as ‘Stuart’, in nightclubs — like The Haçienda in Manchester and Powerhouse in Newcastle, as lesser known venues in Blackburn and York – he went by his middle name, ‘Linden’.

He tells DJ Mag about the mechanics of this double life. “I was young and foolish,” Rhodes recalls. “I would be in the classroom from nine ‘till five. Then I’d make sure I had everything I needed — my 35mm film, my pen, paper and all the rest of it — get a couple of mates in the car and off we’d go. We wouldn’t get back until some time in the morning.

“If I was doing a feature for Gay Times, I’d go and do the photography, then on the way home I would stop off at the parcel office, put the film into jiffy bags, post it to the magazine, go home, grab a couple of hours sleep, go to work at the college, get home again and write the article. Then I could finally go to bed.” This went on for a decade.

During the 2020 lockdown, when stabbing yourself in the eye became more preferable to watching another true crime documentary on Netflix, he went into his loft, dusted off his old negatives, pulled out his printed articles, and set about a marathon of scanning. This resulted in the birth of the @linden_archives Instagram page.

The body of work depicts an abundance of unmitigated queer joy. But it was set against a backdrop of both heartache and suffering caused by the HIV/AIDS epidemic and a militant era of political oppression. In 1988, Margaret Thatcher enacted the ‘Section 28’ law that prohibited local authorities and schools from “promoting” homosexuality. It also outlawed — much-needed especially in the context of the medical crisis facing that community — councils from funding LGBTQ initiatives.

Rhodes’ work is now being memorialised in an upcoming book, Out & About With Linden, which will be released in March 2022 and includes written contributions from a bunch of people including Boy George, Mel B, and Paul O’Grady. We asked him to take us through some of the imagery.

Pride in Manchester City Centre, 1993

“When I look at this, I can’t believe that I was there. This was at an open-air pride event in Manchester in 1993. At the time, [Sir] James Anderton, the police chief in Manchester, was causing a lot of trouble for the gay community. There was a lot of protest about him and his policies.

“Lily Savage [Paul O'Grady’s character] was on stage and she suddenly pointed out to the crowd that at the back on the wall were plainclothes police officers. They were watching the event and taking down car number plates. The crowd turned as one and went for the officers. I was at the front of the stage taking pictures and somehow I managed to run round the side of the stage, across the road so that I'm now looking at the front of the crowd.

“By then the police had gotten into their unmarked police car trying to get away, but the crowd was gathering around the car. Then two lesbians threw themselves on the bonnet and started snogging. The perplexed officers didn’t know where to look, what to do. They were absolutely paralysed. The crowd was cheering and carrying on. They wouldn’t have harmed them, but they embarrassed them; pointing and laughing at them, exposing them as the bigots they are.”

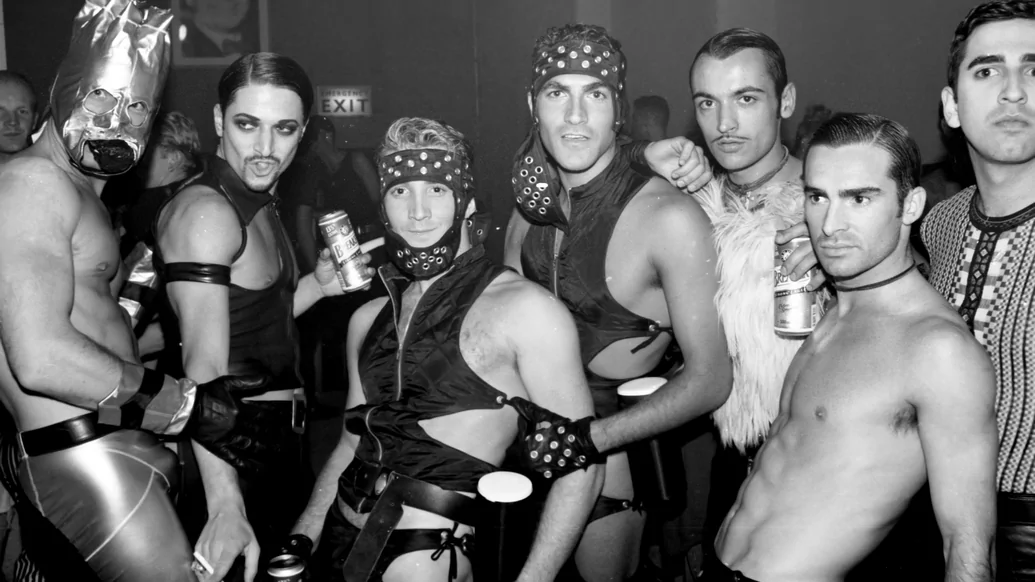

Flesh at The Haçienda, 1993

“I was a regular at The Haçienda. Flesh was one of those nights where people went to misbehave; to dress outlandishly and behave to the extreme. It was leather, assless chaps, and all that. The people that were playing around with fetishwear were at The Haçienda. That was a little gang of guys and I think some of them, if not all of them, were employed by the club night organisers to entertain the crowd. That [second to the right] is Louie Spence, he became famous in his own right.

“Flesh was the Studio 54 of Manchester in a way. But there wasn’t disco music, that would be the last thing they’d play – it was hardcore dance music. Anyone could go, it wasn’t like Studio 54 in a sense that if you didn’t have the right look you weren’t coming in. You could be standing dancing next to anybody; there was one night in particular — it was ‘no cameras allowed’, unfortunately, I had to put my mine away — I found myself dancing next to the likes of Howard Donald and Jason Orange and Robbie Williams of Take That. It was that sort of club.”

Bliss, Newcastle, 1994

“This was around World AIDS Day in December, it was a charity fundraiser for the Terrence Higgins Trust, the Newcastle-based support group for gay people. It was a big party night, you can see the people hanging around the back. Everybody's got the ribbons [the symbol of solidarity with people living with HIV/AIDS] on. It was a great night.

“The acid house scene, with whistles and glow sticks, hadn’t arrived on the gay scene in Newcastle at that point. That came much later. It was disco and high energy — that’s what filled the clubs there in those days.

“The ‘80s was a boom time for the HIV/AIDS epidemic. These photographs, from the ‘90s, follow on from that. Yes, AIDS was still rampant. But for the gay community by then it was like coming to terms with the [COVID] pandemic. We've had two years of COVID, now people are coming to terms with it and learning to live with it. How does life carry on?

“When the epidemic kicked in, people were terrified and it caused a lot of problems. But by the ‘90s people thought we can’t not go out, we can’t not party, we can’t never have sex — we have to find a way to carry on. We need to wear condoms, which is a bit like wearing a mask. We need to find a way of getting through this. And that's what these photographs show.”

Milk and Honey in York, 1994

“This was in a disused church. York is a big city, but it’s a rural farming community. The people that went to Milk and Honey were coming from country villages. This is their big monthly night out.

“They played straightforward mainstream dance music: if it wasn’t in the charts and on the radio they weren’t playing it. There were a lot of 12" disco remixes, extended versions of Donna Summer and things like that. It was a much more relaxed atmosphere — you wouldn't find the extremes of Flesh or Paradise Garage there.

“It was a bit more cruisy because it was your only opportunity to get laid if you lived in North Yorkshire. Your prospects of meeting someone for any sort of sexual encounter outside of this club was pretty grim. It was your pickup night.”

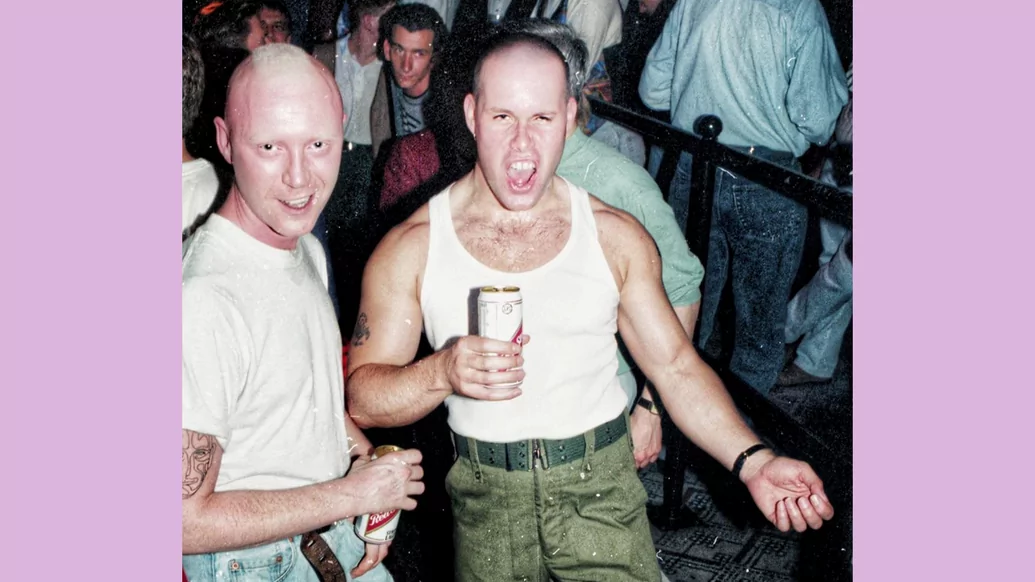

Powerhouse, Newcastle, 1995

“This was at Powerhouse in Newcastle. [It was] absolutely huge. The music was a lot more powerful, it was a lot more dance-orientated by 1995. It was all about getting on the dancefloor and staying there all night.

“An interesting thing about Powerhouse was that it had a room at the back which was one of the last ‘men only’ rooms that I ever came across. It contradicts the rest of the images in some ways, which show a lot of unity. The guy on the right-hand side is getting an eyeful of the dancer, he’s almost drooling. The fashion is getting more baggy, you’ve got the baggy trousers. And who goes to a nightclub wearing a sweater?

“Loads of people get in touch because they see themselves or find their friends. If you troll through the Instagram account and look at people's comments some are quite interesting. There have been two main types: people who are absolutely thrilled to bits, they didn't know this picture existed and had forgotten all about that night. Then you get the sad or poignant ones, where people go, ‘Oh, thank you for sharing this picture. This is my partner who died.’ Because, you know, 30 years is a long time — a lot of people have sadly passed away.”

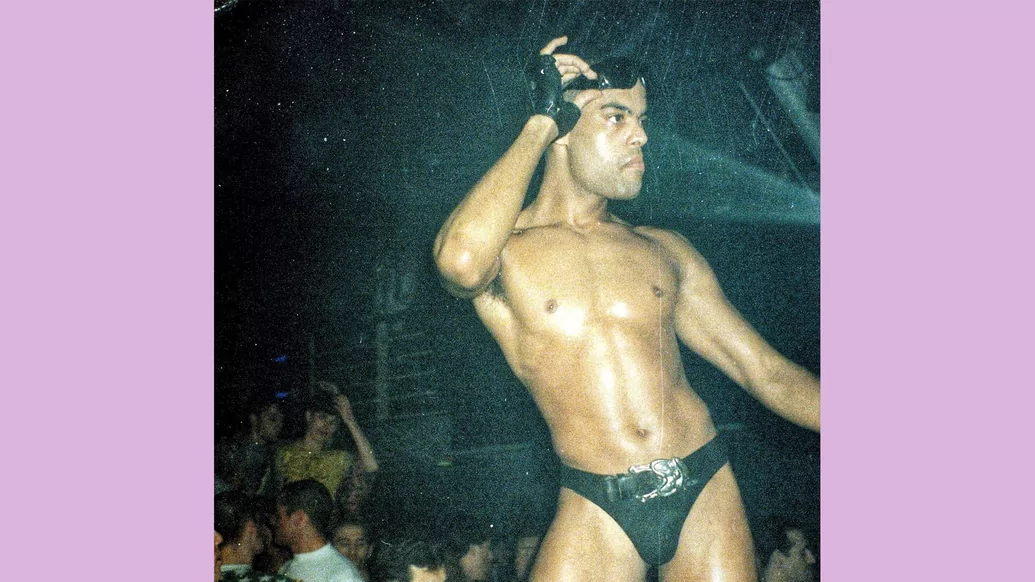

Flesh at The Haçienda, 1992

“This was in Flesh in 1992, they had podium dancers in those days. It was just a giant party. Fashion and the way you dressed was becoming more important to the younger crowd, but was a huge mix: you’ve got the guy with the moustache at the bottom who’s quite happy to turn up in his t-shirt, but the guy behind is wearing the stars and stripes top. Dress style was very individualistic.

“In 1997, The Haçienda was over. There's a natural lifespan to these things, like a boy band has a natural lifespan of three to five years. These club nights and fashion and music trends have the same sort of lifespan. Everything changes. One minute a venue is in favour and the next something shinier or brighter has come along and you’re finished. The good club owners knew that and they’d already have started planning and developing a replacement by then. They’d say, ‘This is the last year for this club night, next year we’re starting up in a new location.’ Good business people knew what they were doing.

“In the ‘90s, Heaven and G-A-Y in London were huge. I mean, major A-list celebrities would be there all the time. Madonna, Kylie Minogue or George Michael would perform at these clubs. Now it’s going to be a runner up from RuPaul's Drag Race. Just let it go. That’s what they did in Manchester, they thought let’s start the next big thing.”

C’est La Vie, 1993

“I didn’t just cover the big clubs in Birmingham, Manchester, Newcastle and Liverpool. I also went to what I called the one-horse towns, the places with one club or bar. C’est La Vie was a full-time nightclub, with a gay night. So, in Blackburn this was the gay scene — the weekly gay club night, on Thursdays, in C’est La Vie. That was it.

“You might have some interlopers who have come over from places like Manchester, but really everybody knows everybody. The bulk of the people there lived and worked in the area of Blackburn. These one night events were for the people who didn’t have a car or couldn’t commute to Manchester, Birmingham, or anywhere else.

“The atmosphere was more relaxed because people felt at home, they were on home ground. So they were more comfortable. They’d be playing mainstream music. The more experimental music would be in the big cities like Manchester. But when you went down to the provinces, Blackburn or Middlesbrough or York, it was more mainstream. The DJ would play much safer with the music; you wouldn't get many trying to experiment with music that hadn’t already been accepted.

“People stuck with the tunes that they were comfortable with. If you wanted to start discovering acid house, at that point, you’d go to Manchester and find somewhere like Danceteria [a notorious Manchester club that opened from Friday until Monday] and you’d go, ‘Wow, this is different.’”