Forging electronic futures in Karachi

Overcoming Pakistan's conservative mindset and sometimes-dangerous political tensions, a small group of artists are building a future for electronic music in Karachi

Around the turn of the decade, there was something distinctly wanting in the Karachi electronic music space. Despite artists releasing tracks, there appeared to be a giant vacuum that no one had attempted to fill. Following the previous decade of violence in Pakistan, coupled with a tumultuous economy, the void of a recognisable electronic music community was predictable.

For decades, there were always rumours of raves at the beach by the Arabian Sea, and jungle being played in warehouses, but the last 10 years have allowed the city’s electronic music landscape to truly take shape. “It started in 2010 when bedroom producers got together,” Karachi-based musician Alien Panda Jury says via Whatsapp. “There was something called Karachi Detour Rampage. They had contacted a bunch of people, and started putting out tracks.”

Karachi Detour Rampage hovered visibly for a minute, before disappearing. Their dormancy sparked the birth of another collective to assume responsibility, one whose effects would be seismic and still felt to this day: Forever South Music. “Like anything in this world, you adapt and evolve in your surroundings,” Dynoman says, the creator of Forever South Music, alongside Bilal Nasir Khan, who makes music under the moniker Rudoh. The duo sparked a movement that grew into a large enough collective for South Asian fans of electronic music to rattle off Karachi-based names in pure admiration: Dynoman, Rudoh, Slow Spin, Tollcrane, TMPST, Eridu, Smax, Alien Panda Jury and many more.

Forever South would go on to be featured in international publications such as Vice, The Fader and DUMMY, while artists from the collective would play across Europe and at famed American festival SXSW. They would also create several records, both solo and compilations. Artists from the Maldives, Germany and Pakistan came together to create the 19-track ‘Karachi Files’, and even cut a four-sided vinyl release from it. “There was a huge purpose in what was being achieved,” Dynoman says. “You were giving something to your city, to your country, something unique and different. I had to learn so much about my own city and how to throw a show in Pakistan and, that too, in a DIY fashion.”

With a community being built from the ground up, Karachi’s electronic musicians found themselves gravitating towards each other and collaborating in a way that was a first for them. “When we all started out, we were very fresh,” Slow Spin, who makes textured, celestial music, says. “We were coming back from other cities we were living in and, in most cases, we had just returned from our undergraduate [degrees].” Bursting with ideas, excited to share how they had grown and what they had learnt in a formative part of their lives, Forever South became the perfect raw breeding ground. “Forever South helped push the scene forward with more structure,” Alien Panda Jury says. “The idea was so interesting, people wanted to be a part of it, so the response was great,” Dynoman adds. “The crowd were there for the music.”

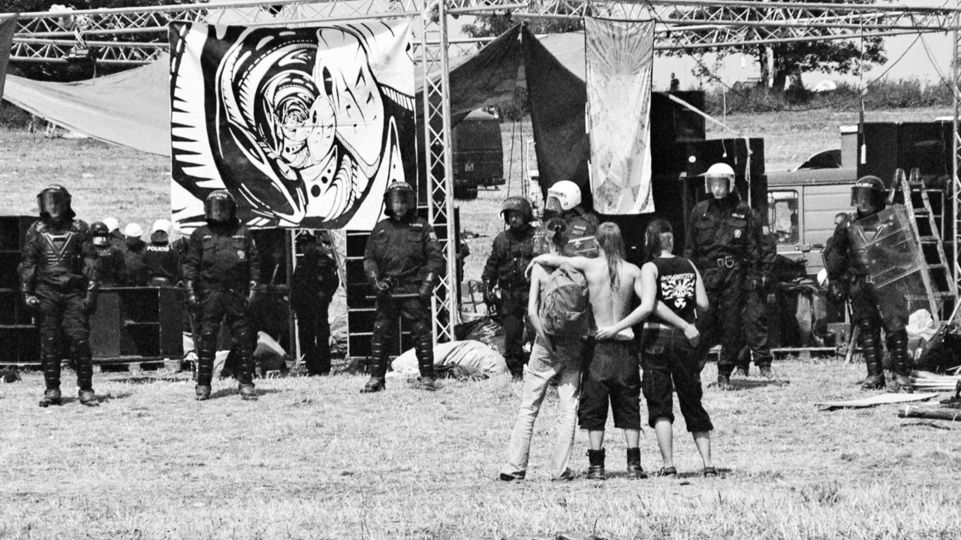

The scene subsisted off youth, adrenaline and restless energy, and that came through in the music being created. “Music in Karachi, especially during the time period when Forever South was happening, was often very chaotic,” Dynoman says. “It was taking strength and inspiration from the city, so if you listen back to ‘Vol.1’ of Forever South, [it’s] raw, hard-hitting and urgent.” Over time, though, fissures started appearing in a scene living on limited resources. After a few years, the biggest crack that formed was security.

The Second Floor (T2F) was an influential cultural hub for musicians in the industrial capital of Pakistan. “We all had our first gig there as 15- or 16-year-olds. We all started there,” Slow Spin says. T2F’s owner Sabeen Mahmud was a progressive activist and social worker, helping guide and advise when needed. In April 2015, after hosting a political talk at T2F that centred around the volatile region Balochistan, Mahmud was driving her car home when a motorbike pulled up alongside the car at a traffic light less than 500m from the venue. A gun was drawn and Mahmud was fatally shot four times. “They brought her body to T2F for the funeral,” Slow Spin says. “There were so many in the arts community that loved her. She had this fearless, wonderfully warm, brilliant personality.”

Mahmud’s murder was a shock to the community. An outspoken creative, she wanted to encourage the challenging of injustice and discrimination at every turn. “[It] was so scary to understand the weight of our decisions, to understand how heavy the repercussions can be,” Slow Spin says. “Everyone had to take a minute [on] how much of a risk they were willing to take, how strongly they felt about their opinions and which ones were worth fighting for. It wasn’t just the fear we were left with, but it was also a lot like humility and responsibility for our actions, for the things that we wanted to do.”

“The city moves at restless energy. Listening to the stuff that comes out of there, it feels like it has the vibe of the city itself.”

The same year Mahmud was murdered, Dynoman left for NYC. His departure created a void in the beating heart of the scene. Politically, tensions also rose in the city, and security became a real threat. “There was a complete and utter lack of chances to play gigs,” Asfandyar Khan, who makes intricate, soulful techno under the name TMPST, says. “I think that has fed into a bit of a malaise in terms of making music. A lot of people are making tracks, but that urgency that was there is not there anymore.” Alien Panda Jury points out how, due to a lack of clubs and bars, “music isn’t a stream of income here”. Slow Spin elaborates further. “We all realised then that we were doing other jobs to help us sustain ourselves. It was maturity and growth, and it’s not something to be viewed negatively.”

Forever South stopped being functional. The collective released a seemingly final collection in January 2017, before, much like their predecessor, Karachi Detour Rampage, they too disappeared. Karachi’s stagnation was heavily felt. The burst of creativity that occurred for the first half of the decade seemed to have dissipated slowly into obscurity. Behind the stagnation, in hidden corners, though, ideas were brewing. Childhood friends Jahanzeb Safder and Daniyal Ahmed came together to create Karachi Community Radio in 2018, which became a space to promote the local Karachi scene. They introduce artists, discuss local issues and culture, do Q&A sessions and have now started doing live streams and hosting events.

“One of the reasons we started KCR was because we knew there were all these artists out there who weren’t performing,” Jahanzeb says. “It’s about creating audiences and finding people in the absence of having mainstream venues.” After a period of inertia, building trust was also crucial for KCR, and they’ve already found a way, by urging previously established artists in new directions. Asfandyar Khan, who makes ambient music under his own name, said KCR helped encourage him in places where others didn’t. “They’ve pushed me to do an ambient set,” he says. “No one else in Pakistan has thought to say, ‘Let’s do an ambient set’.”

Karachi seems to have awoken from a deep slumber. “[The city] moves at restless energy,” Abdul-Rehman Malik says, who runs Pakistan’s only true alternative music blog, Mosiki. “Listening to the stuff that comes out of there, it feels like it has the vibe of the city itself.” Slow Spin echoes Malik, mentioning how, “I think we all have been trying to hone in on our craft a little more. I think everyone’s trying to really further develop their materials, their sounds, their selves. Everyone here is trying [to] recollect themselves, and release some new stuff relating to our environment.”

In Karachi, everything is purely DIY — so much so, that Asfandyar complains that: “There’s no club or promoter that would say ‘I’m going to get CDJs, because that seems like a good investment’.” With no framework in place, the scene always feels like it’s ready to collapse; but with each new wave that occurs, the city’s base seems to become sturdier. “When you don’t have any kind of structure that would put the whole thing in place,” Daniyal of KCR says, “then it comes down to you to build that community and ecosystem. That’s what we’re focusing on.” Alien Panda Jury, who left Forever South collective and now hosts Sine Valley Festival in Kathmandu, Nepal, underlines the struggle the scene faces.

“Obviously, it’s an uphill task,” he says. “It’s never easy, because of the conservative mindset, but things still happen in pockets in Karachi. There’s nothing you can do to stop people from having fun.” Having found inspiration in Kathmandu, Alien Panda Jury realised that if he can put on shows and a festival in another country, he can do it at home, too. “That’s why I started Oscillations [a series of events], because I really owe Karachi,” he says. “I need to focus and bring people out again. We’re trying to create that scene again.”

The artists that inhabit the city seem genuinely thrilled. “It’s exciting to imagine where we’re going to take this next,” Slow Spin says, looking towards the next decade. “Karachi is definitely the kind of place that influences the way you move through it, because of all its invisible and visible barriers.” Despite not living there currently, Karachi still plays on Dynoman’s mind, and he looks towards it with hope. “There’s this element of danger that you grow up with in Karachi and as Pakistani,” Dynoman says. “This is reality. You can’t turn around. You have to make the most of your situation.”