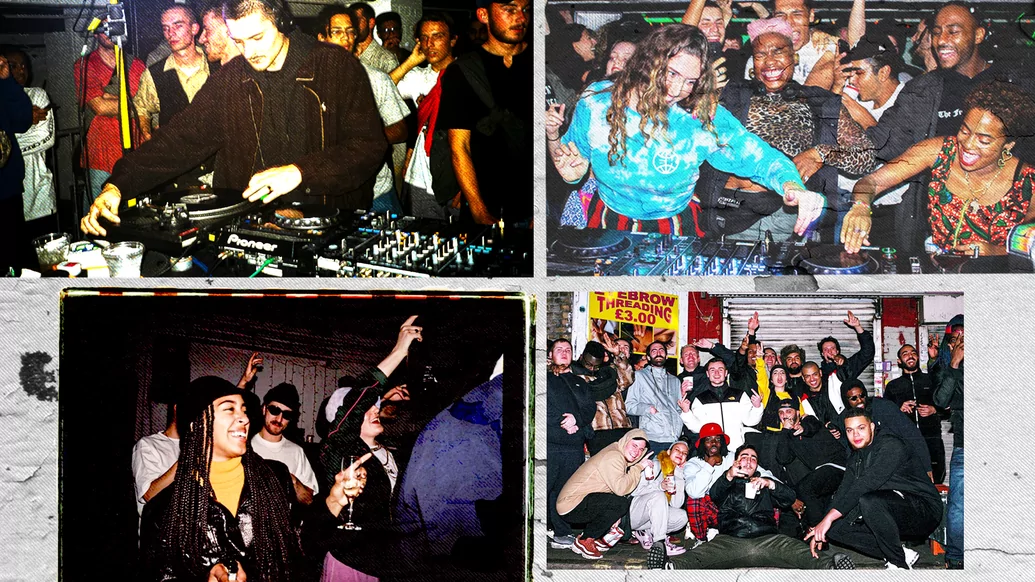

How free parties are shaping a new generation of UK ravers

In response to big room club culture, a number of grass roots promoters, venue managers, artists, and opportunists are seeing success from putting on free parties in legal spaces. Martin Guttridge-Hewitt explores their impact on electronic music in the UK, and what the future holds for this vital part of our scene

Last year’s International Music Summit report showed that over one-fifth of British nightclubs closed in the year to December 2018. The tip of a more worrying iceberg: The Guardian claims an estimated £200million was wiped from the country’s nightlife economy in the five years before that.

One theory is that people are less interested in the hedonism associated with clubbing, in tandem with growing trends in sobriety and healthy living. Another involves soaring running costs hitting small- to mid-sized dancefloors hard: not least through booking fees, which have long-been inflating amid headliner culture, and as large venues and major dance events push expectations ever-further.

Their success suggests that while raving isn’t over, punters want a lot of bang for their buck, and buying power to supply that predominantly lies with large brands. The increased cost to attendees led us to ask if British clubs had moved from egalitarianism to elitism last year, arguing that the middle classes rule booths, green rooms, and bar queues. Meanwhile, club residencies, a vital incubator for fresh talent, have declined as big rooms struggle to carry small names under the weight of idols.

It’s a troubling picture, but there are counterpoints. Promoters, venue managers, artists, and opportunists are pushing back through free sessions in legal spaces.

“It was set up with the intention of doing nice cocktails and tapas, but [we] turned it into a bit of a rave,” Stuart Forsyth, the former booker at Leeds spot Distrikt, says of how it began. Over the last 11 years, the 150-capacity bar-and-restaurant has welcomed names like Moodymann, Derrick Carter, Green Velvet, and Kevin Saunderson, without charging door tax.

“It took a bit of time, as obviously we were trying to get people down for a fair price that worked for us with it being free entry,” he continues. He would often double up with promoters elsewhere in the country to secure big-name guests in the early days. “Word got round about Distrikt, and pretty soon people actually wanted to play at it.”

“I think these are the places where you’re sort of moulding the next generation of producers, promoters, potentially venue owners, DJs” — Kristian Birch-Hurst from Birmingham’s Freedom of Movement

Now under the tenure of manager Matthew Bowles, the venue is in rude health, with an enviable upcoming calendar; Cristi Cons & Sammy Dee, DJ Tennis, Cartilus Music. Easter Weekend welcomes house music master Kenny Dope. But it’s not just about big guns.

“I think Distrikt is one of the best venues in Leeds for giving opportunities to younger people. We’ve started doing open deck nights, which we never did before: for new people to come and play a class venue on industry-standard equipment, just to give them a chance,” says Bowles.

Breaks troupe 199, the logically named House of Tech, and eight-year old deep stompers Albion Records, are all examples of more established crews that regularly call Distrikt home. “It’s become a little family, between promoters, the crowd, a lot of regular faces.”

Birmingham’s Freedom of Movement works differently. Taking its name from the UK’s post-referendum climate and an open-ended music policy, it forsakes a central location for the upstairs of suburban Moseley pub, The Dark Horse. A three-man team runs the decks all night, every night: Kristian Birch-Hurst, AKA Trieste, Christy Lakeman (of Birmingham’s respected Cafe Artem record shop) and dub producer Goosensei, or Matt Goose.

“I had so many run-ins with agents who would present me with absolutely outrageous costs for DJs who just didn’t have the pull,” says Birch-Hurst, who’s also involved with the ticketed Voyage and Leftfoot parties. “We put our heads together one evening and thought about running a party that wouldn’t burn a hole in our pockets, where we could be really fluid and open with the music policy.”

Describing the Freedom of Movement sessions as “pretty fucking DIY”, the informal setting has garnered a diverse crowd. 50-year old pub drinkers hang out around undergraduates and technoists skank with roots fans. On one occasion, A-Level students brought their parents. According to Birch-Hurst, both generations stayed all night.

“I think these are the places where you’re sort of moulding the next generation of producers, promoters, potentially venue owners, DJs,” he says, arguing that free entry parties have a more sociable atmosphere. “All of these spaces have the power to inspire people to go off and do their own thing, which is vital for the longevity of a music scene.”

London’s Keep Hush has certainly inspired its attendees. To access events, which are musically focused on the experimental and bass-heavy “hardcore continuum”, membership is required, but free of charge and open to anyone. So far, 11,000 people have joined Keep Hush across the UK.

Freddy Masters, who founded the setup with Fred CC, believes that crowds are more likely to take risks, and explore new sounds and artists, when they don’t have to pay in. The event history can be traced back to another unusual setting; a Soho office where the two friends worked as cleaners having relocated to the capital from Oxford. The building owners opened a basement, and the pair saw an opportunity.

“The original idea was to invite DJs in to record and stream mixes. We already had a mix series and therefore relationships with a few DJs and mates who were making really good music,” Masters recalls. Early sets attracted a handful of heads before things developed, with repercussions. “We got kicked out of the space,” he admits. “We ended up having a load of the grime scene coming down, and the next day the whole office building just smelt of beer and weed, and cigarettes. The company, from their side, were just like, ‘Wow, you’ve really taken the piss.’”

Losing that haphazard home was just the beginning — Keep Hush’s brand is going strong. They’ve hosted parties in Bristol and Manchester, their spin-off event Technics & Chill sees hopefuls apply for a shot at mic or turntable duties, and sister party Club Turbo has just become a weekly Friday at the Dalston venue formerly known as Alibi. As well as running these nights, they have also used this venue to host a month of parties, panels, workshops, and more, under the name Secret Location.

Masters agrees that there are not enough spaces offering limelight to hopefuls, and concedes that crews built on close connections can be at risk of forming cliques. “Based on the response we get when we put out an opportunity to get involved, I would say it’s definitely lacking,” he says. “A lot of nights are way too closed off [and] that’s something we’re conscious of. One of the reasons we started Keep Hush was the seeming unapproachability of venues or other promoters... we actively had to avoid falling into that, as it’s quite a natural way to work.”

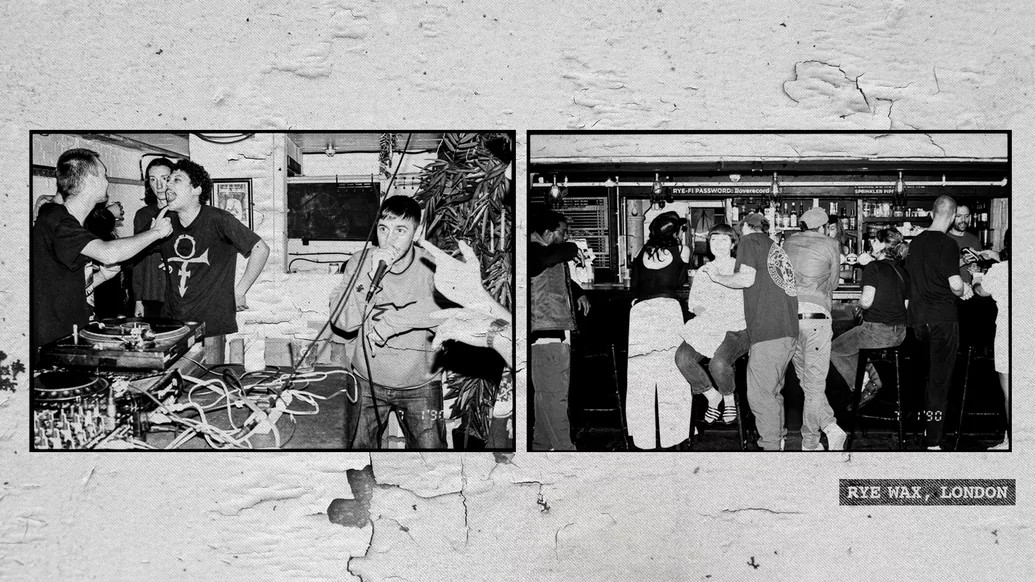

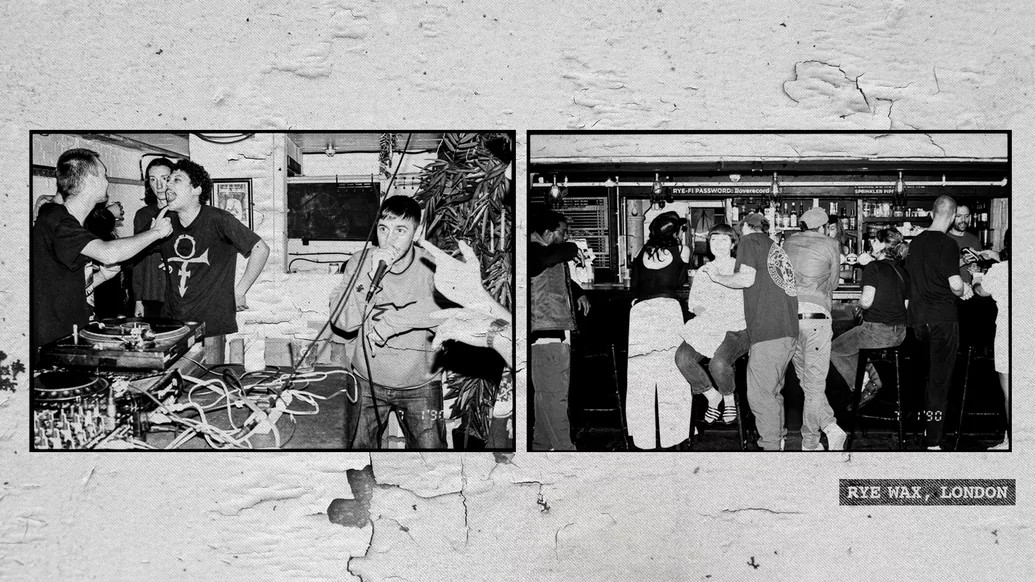

London’s Rye Wax, which turns six this year, has played an integral role in allowing Keep Hush to blossom — giving Masters and CC a venue when they lost that original Soho basement. The relationship continues to this day. Rachael Williams oversees nine weekly events at this part-record store, part cafe-bar, part-club, in a Peckham cellar. The majority of the parties have no entrance fees, and have recently hosted artists like Peverelist, Louise Chen, and Nabiyah Iqbal.

“To put on a free event you have to do it for the love of it, and I think it’s great we’re able to do that, but I don’t think [that model] should be adopted wholesale” — Rachael Williams from London’s Rye Wax

“It’s a community environment and everyone is just like,‘Come down and have fun’,” Williams says, explaining that Rye Wax can only function in this way because staff are embedded within London music culture. Current employees include Chris Watson of FYI Chris, and DJ and producer Medlar. “We are all out there, going to other parties, meeting people — it has this knock-on effect.”

But Williams doesn’t see this model as a real solution to the financial problems plaguing UK nightlife. Although she’s keen to provide platforms to young players, reliance on bar takings can be restrictive when it comes to line-ups. A name needs recognition to pull people in at peak hours when London, despite the mass closures, still has so many venues.

“I do believe you should be paid what you’re due in terms of fees. I DJ myself,” she says. Guests contact her to play in many instances, and are never expected to forsake their regular commitments. “DJing should be relatively well paid, not silly money. To put on a free event you have to do it for the love of it, and I think it’s great we’re able to do that, but I don’t think [that model] should be adopted wholesale.”

It’s a fair point which leaves us facing the reality of how complex the cash flow crisis in British clubs is, with wage stagnation, gentrification, land value, and a lack of respect for dance music as a culture all at play, not just fees. The situation is about to get much worse, too — industry body Phonographic Performance (PPL), has proposed a 125% increase in royalty charges for venues playing recorded music (i.e. DJ sets) by 2023.

In even more recent news, by January 2021, EU artists will need visas for UK dates. It seems unthinkable that Europe will do anything other than reciprocate, which could mean that homegrown artists garner less European bookings and increase fees for domestic dates to compensate. Williams says this would be “a disaster for us all”.

In contrast, British promoters now know they face more overheads and paperwork to draft continental names. Bowles sees collaboration as essential to overcome these new obstacles. “There’s already groups on Facebook for UK promoters, where people talk about helping get people over through travel shares. I think we will get more of that vibe to make it work.” Whatever the fallout, change seems inevitable and grass roots are in the direct firing line, so it’s wise to make the most of what’s currently here, while you still can.