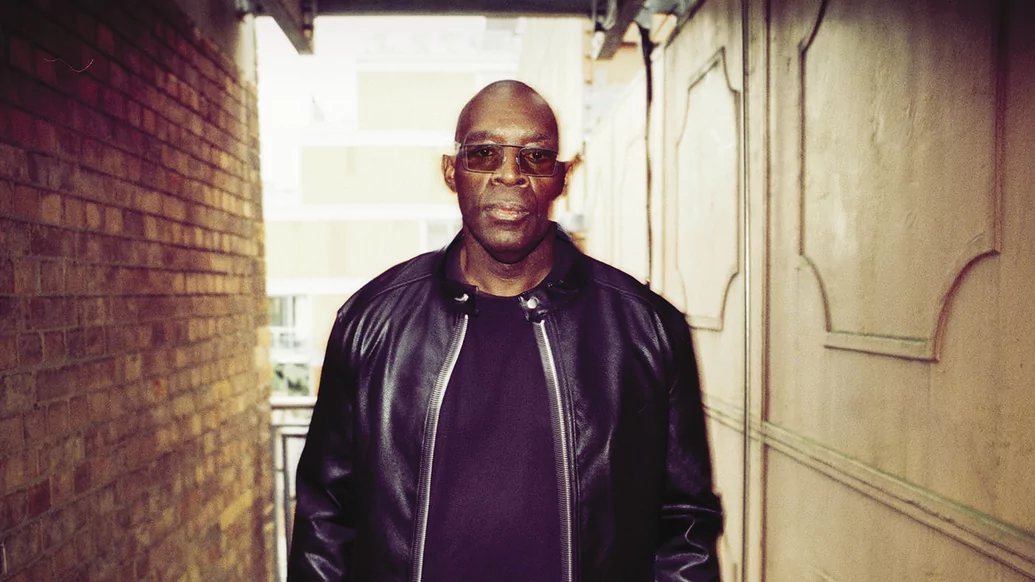

Kevin Saunderson: the E-Dancer returns

Techno would not exist as it does today without Kevin Saunderson. Some of the Detroit techno architect’s most revolutionary work has been released under the E-Dancer banner, and this month sees the release of ‘Re:Generate’, a collection of classic E-Dancer tunes remixed by a world-spanning array of producers. Busier than he’s been in years, Saunderson took time out to talk to Bruce Tantum about the release, his lengthy history and his weighty legacy

Techno is the language of machines speaking to each other, the vocabulary of shiny circuitry, the sound of the future in the here-and-now. But when DJ Mag attempts to connect with one of the music’s foundational figures, things get off to a somewhat technologically shaky start. Zoom connections freeze, screens suddenly go black.

Finally, the signal is coming through strong, and there he is — Kevin Saunderson, one of Detroit techno’s originators, known to some as the Elevator — sitting in his car, his phone propped up on the dashboard as the sun pours brightly through the windshield. “I was trying to do the interview in that Panera’s back there,” he says with a bit of exasperation. “That wasn’t happening. But we should be good to go now.” And with that, the screen goes black once again.

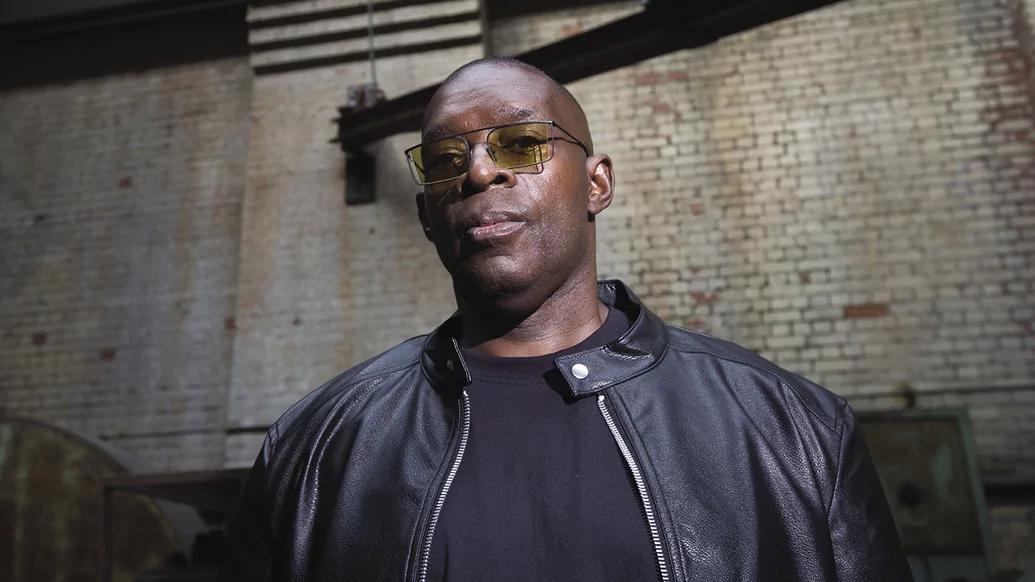

It turns out the sunshine had overheated the phone, but once Saunderson, 57, gets that sorted out, he — finally, truly — is good to go. He’s sporting mirrored shades and a sleeveless black T-shirt. He could easily pass for the big-time pro football player that he once dreamed of becoming, or at least a retired version thereof. “I’m just coming from the gym,” he says — sure enough, a post of him working out with a boxing trainer shows up on Instagram the next day. Saunderson’s not here to talk about workout regimens, though. Instead, the topic for discussion is one of his two most well-known alter egos, E-Dancer. (The other, as anyone with even a glancing knowledge of dance music knows, is the techno-pop unit Inner City — much more on that later.)

From 1991 through the early ’00s, E-Dancer served as Saunderson’s main outlet for his tougher productions, brimming with tribal-tech rhythms and thrumming basslines. One could make the case that he cleared the way for the kind of propulsive, stripped-down, introspective style that defines a large subset of the techno made now; deep and brooding, yet buoyant and forcefully funky, Saunderson concocted a style of music that reverberates today.

Version Quest

The occasion for this interview is the release of ‘Re:Generate,’ a collection of reworked tracks, many off the fundamental 1998 album ‘Heavenly,’ with mixes coming from Detroit doyenne DJ Minx, Berlin mainstay Len Faki, Brooklyn breakthrough Tygapaw, and the UK’s Paul Woolford in his Special Request guise, among others. It’s the first album to bear the E-Dancer moniker since 2017’s ‘Heavenly Revisited’ — which was basically a newly mastered version of the original, with some light Saunderson retouches — and 2018’s ‘Infused,’ which featured orchestral versions of classic E-Dancer cuts.

‘Re:Generate’ is on Drumcode, the techno steamroller run by the Swedish DJ and producer Adam Beyer. “Adam and I would see each other now and then,” Saunderson says, “bumping into each other at festivals. Finally, I said, ‘Adam, let’s just do a record together.’ But he was so busy — and I was busy, too. Finally, I reached out to him during the shutdown, and said, ‘Well, we all got more time now!’” As discussions went on, the collaboration gradually became grander in concept, finally settling on the framework of what would become ‘Re:Generate’.

Oddly, despite the iconic status of many E-Dancer tracks, most of them had never been revamped by Saunderson’s fellow producers. “I’ve never had many people remixing E-Dancer,” he says. “Even when I had Carl Craig work on ‘World Of Deep’” — he’s referring to the swirling, ever-expanding Craig version that appeared on ‘Heavenly’ — “that wasn’t really a remix, more like just a mix.” There were plenty of unofficial E-Dancer edits floating around, though, some of which would end up in Saunderson’s inbox. “Sometimes I would like them. And sometimes I would play them!” he adds with a laugh.

Beyond the simple fact that E-Dancer remixes were a rarity until ‘Re:Generate’, Saunderson had an ulterior motive as well — he realized the collection could serve as a marketing tool of sorts. “Why not do a remix album to introduce E-Dancer to people who might not know about it?” he asks. It’s a fair question: For older techno fans, the idea that someone might not be familiar with E-Dancer may seem preposterous. There are, however, plenty of younger electronic music fans who weren’t yet born when Saunderson launched the project in 1991. By then, Kevin already had the kind of life that most artists can only dream of.

Most students of clubbing history know the broad outlines of Detroit techno’s early days, of how three enterprising young producers — Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson — concocted a new form of dance music in the mid-’80s, seemingly out of thin air. Together known as the Belleville Three, named for the semi-rural town just outside of Detroit where they were based, they took bits and pieces from Chicago house, new wave, synthpop, Kraftwerk, industrial, Funkadelic, and more, messed around on some cheap gear and, just like that, techno was born.

The truth is considerably messier: As with Chicago house, everyone involved has their own who-what-when-where-why version of the tale. And there were plenty of other Detroit-area artists, people like Eddie Fowlkes and James Pennington (aka Suburban Knight) who also played major roles. Further complicating the story, the Belleville Three itself was hardly a monolith, and each member of the trio took a different path to techno glory. By the time techno became its own genre, Atkins, the quiet philosopher of the three, had been working on music for years — most notably via Cybotron, the electro-with-guitars band that first became active in 1980. May, who in the past year has been accused of sexual assault and harassment by numerous women (he denies the accusations), essentially served as the music’s unofficial spokesperson in its early years. Saunderson? Mainly, he just wanted to make people dance.

Paradise Found

That make-’em-dance ethos is most likely due to nurture as much as it is nature. Saunderson isn’t originally from Detroit, or even Belleville — instead, he’s a born-and-bred New Yorker, living in Flatbush, Brooklyn full time until the age of 10, when the family moved to Belleville. But even then, he would spend much of his time back east — his parents were together, but his father stayed in New York for his job, and Saunderson would travel between the two, spending summers with his dad.

Even as a child, he was experiencing the music business first hand, thanks to his older brother Ronnie, who worked as a road manager and engineer for top-tier funk combos B.T. Express, Brass Construction, and Skyy (the three groups shared members). Even at an early age, Saunderson had long been soaking up funk, disco, and R&B via the influential NYC radio stations Kiss FM and WBLS. “Ronnie would just bring those guys by the house, and since I knew their songs from the radio, that was pretty cool,” he remembers.

When Saunderson was in his later teens. he decided that he wasn’t going to let his time in what was then the nightlife capital of the world go to waste. In the late ’70s, the New York City area was awash in groundbreaking selectors, and he experienced some of the all-time best: David Mancuso at the Loft, Tony Humphries at Zanzibar and, especially, Larry Levan at the Paradise Garage.

“One day, my cousin said, ‘Come on, we’re going out to the Paradise Garage,’” Saunderson recalls. “I didn’t know anything about it, but after going the first time, I couldn’t wait to go back the second and third times, pretty much any time I had the opportunity. It was an enlightening experience. I mean, the place was all gay, or 90 percent gay, and before then, I didn’t know anything about that kind of sexuality.

“But seeing the way that people danced at the Garage, and experiencing that love of the music they had... that was something. Me and my cousin, we’d just be in our own worlds, in our own little areas, dancing away.”

That world was created by Levan, and Saunderson sees his nights at the Garage as early lessons in the control a DJ can have over a crowd. “At that point, just hearing mixing was something new to me,” he admits, “but even then I could tell that Larry was very good at those transitions. He might play one record for 30 minutes, 40 minutes, maybe an hour, and he would make it exciting. Like [Chic’s] ‘Good Times’ — he would just start that record over and over again, and the crowd would go crazy.”

It didn’t hurt that the Garage’s setup, designed by the fabled audio engineer Richard Long, was one of the best club systems to ever have existed. “Just hearing that kind of soundsystem, where you really feel the pulse of the bass hitting your heart, was something I’d never experienced before.”

Back in Belleville, well before his Paradise Garage experiences, Saunderson had been going with May to Atkins’ house, where he experienced music from a much different angle. “Juan had some equipment there, mainly a couple of old synths — well, they probably weren’t old at that point — and multiple cassette decks, and all these different systems mixed together,” Saunderson says. “He was trying to figure out how to do things creatively. But that didn’t really spur my passion to actually make music, even though I loved music.”

Still, it’s hard to imagine that seeing Atkins’ nascent production stirrings didn’t spark something, and by the time of Saunderson’s Garage visits, diving headfirst into music probably didn’t seem so farfetched.

Hey DJ

The seed had been planted, but first it was off to Eastern Michigan University in nearby Ypsilanti, ostensibly to study telecommunications — “I even had a campus radio show, with maybe two or three people listening” — but mainly to pursue his football dreams. “I got through the season and got to our spring-training period,” he says, “but at the same time I was going to these campus parties, and they had DJs who were playing pretty cool music, a lot of disco but a lot of other stuff as well.”

Saunderson soon hooked up with a crew who were throwing campus parties. “I started hanging around with those guys, and guess what they had? Technics 1200 turntables! And all this great music, too.”

Through them, he ran into his soon-to-be fellow pioneer Eddie Fowlkes. “Eddie was the one, more than anyone else, who really inspired me to take the DJing seriously. He was one hell of a DJ, even though everyone was playing all the same records. At that point, I knew I wanted the opportunity to do what they were doing. I wanted to learn how to mix.” Within a month, he had dropped out of the football program to try his hand at the DJing arts. Then, there was the final push toward Saunderson’s new path.

“I came across this pamphlet,” he remembers. “‘Do you want to learn how to mix? Come to our DJ seminar!’ So I did. I drove up there, paid my 50 dollars, and went through whatever they had to show us — how to cue, how to start your mix, how to count BPMs, everything. Before then, people weren’t telling me how to mix — you just had to get on it and learn. That seminar helped give me insight. I couldn’t afford 1200s, but after that seminar, I went out and bought some belt-driven turntables. I practiced and practiced and practiced, with a lot of disco, Juan’s music, stuff like ‘Planet Rock,’ [Twilight 22’s] ‘Electric Kingdom,’ Egyptian Lover, Hugh Masekela’s ‘Don’t Go Lose It Baby,’ ‘Blue Monday,’ Kraftwerk, whatever was around. And that’s how I became a DJ.”

“My passion is definitely just as strong as ever... People don’t understand how I just keep going and keep going and keep going. But this is me”

New Sensation

Soon, a different style of music was coming into the picture. “Around six months later, I started hearing stuff like [Chip E’s] ‘Time To Jack’ and [Steve “Silk” Hurley’s] ‘Jack Your Body,’ all this Chicago house music,” Saunderson says, “but there wasn’t really much of it. So I’m playing all these same records all the time — what else can I do?” He took it upon himself to rectify the situation.

“I felt like there was a void in the market,” Saunderson says. “There wasn’t a lot of music being made that would use all this new technology that was around — the 909s, the 808s, whatever — that would make you want to dance. So I had the vision that maybe I should make the music.”

First came rhythm. “I was a 909 freak,” he says, “so it began by me just making drumbeats. Eddie Fowlkes had a 909, and would take it to his gigs, so I got my own 909 to bring to my own gigs, using my own beats. I was using my own beats as a bridge, to give a different feel with my different patterns. That was cool, but it needed more than that. I started figuring out how to add basslines and chords, and learning about MIDI and sequencers and all technology.” Other early pieces of gear included the Yamaha DX100 synth, “and either a [Casio] CZ-1000 or 2000 — I can’t remember which one.”

Saunderson’s debut release was ‘Triangle Of Love,’ released as Kreem on Atkins’ label Metroplex in 1986, and the following year on Saunderson’s own KMS label. Co-written by Saunderson and Atkins, it was a grinding tune with a melody that bore the DNA of ‘Blue Monday’. What set the track apart was its use of sung vocals — “a girl named Jeannine, who was a girlfriend of James Pennington” — which was a rarity in the still-new techno scene.

“I can be dark, but I’m a vocals guy, too,” Saunderson says. He attributes that, in part, to his time at the Paradise Garage. “When I made that record, I’m thinking Larry Levan, I’m thinking Chaka Khan, I’m thinking Evelyn ‘Champagne’ King. All us Detroit guys, we were all using the same machinery, which led us all down the same path — but I was trying to make music that was a little bit more related to the disco that I was influenced by.”

The tune wasn’t a hit, exactly, but it did garner a good amount of club play. “I felt like it got a good first-record reaction,” he says. “But the best was that after it came out, I was in New York sitting in my father’s apartment, trying to explain to my brother that I was making music now. He was like, ‘What? You’re making music?’” While that conversation was going on, Tony Humphries’ pioneering mix show on Kiss-FM was playing in the background. “And as soon as I said that, Tony played ‘Triangle Of Love.’ I couldn’t believe it!” That was enough to tell the budding producer that he was on the right path.

Kreem was the first of many pseudonyms. “There was Intercity, which was me, Derrick, and James Pennington,” Saunderson says, counting them down. “The next one was Reese and Santonio [with Santonio Echols], then Reese, then Tronikhouse. There was Kaos [sometimes spelled “K-os”], which was me and my wife at the time, Ann.” (Ann Saunderson would later provide vocals for mid-period Inner City.) There were others, like Transistor, a collaboration with Art Forest, and a one-off with Scott Kinchen called 2 The Hardway. “I just had all this energy to make music, and a lot of different directions to go in, and I wanted it all to be out there,” he says.

One of the highlights from Saunderson’s early discography was 1988’s ‘Just Want Another Chance’, a deep track, credited to Reese, that featured what would become one of his signature sounds. Forever known as the Reese bass, sampled or copied by countless techno, drum & bass, and dubstep artists, it’s a rumbling, unearthly beast, with teeth that sink into your gut if experienced over the right system.

“The sound is the key to a lot of my music,” Saunderson says. “I might start out with a basic patch, but it never really stays that basic. I get inspired by getting into parameters, isolators, messing with all the knobs. When it works, it gives you this high, and once you feel that, the rest of the track comes out automatically. That’s how the Reese bass happened. I was just thinking of hearing that bass in a place like the Paradise Garage.” Sadly, he never got the chance; the Garage had closed the year before.

Around the time that records like ‘Just Want Another Chance’ were hitting the shelves, Detroit techno started to find its way to the British music press. The music’s post-industrial, futuristic mythology became a prevalent part of the story. “You know, I was cool with all that, but I wasn’t the guy who read Alvin Toffler. When I did finally learn about Future Shock and all that stuff later in life, I could see why Juan and Derrick were thinking that way.”

Whatever the philosophy behind the music, the Belleville Three were now world-renowned producers and DJs. But Saunderson’s life was about to take a major turn, and for a while there wouldn’t be much time for any DJing at all.

City Life

“It’s a chord sample [from Nitro Deluxe’s 1987 house track ‘Let’s Get Brutal’] that James Pennington blended with another sound, and added some delay,” Saunderson says of the instantly recognizable chiming tone. The chord is the basis of 1988’s ‘Big Fun’ credited to Inner City, which played a major role in how the rest of his life would unfold.

‘Big Fun’ first appeared on the ‘Techno! The New Dance Sound Of Detroit’ compilation, after which things started happening very quickly. With its bouncy pop-house feel, and its good-time lyrics sung by Paris Gray — “We don’t really need a crowd to have a party / just a funky beat, and you to get it started” — the track was a massive hit, scoring the number one spot on the US dance charts and becoming a worldwide pop success.

The similarly immense ‘Good Life’ quickly followed, as did a string of charting singles like 1989’s ‘Do You Love What You Feel,’ and 1992’s ‘Pennies From Heaven.’ Inner City, now a live act, consumed his life.

“When Inner City took off, it really took off, and I wasn’t ready for it,” Saunderson says. “I wasn’t looking to be on Top Of The Pops, standing behind a keyboard pretending to play. I’m not even a real keyboardist! Interviews, TV shows, traveling to Japan and Brazil — it was unbelievable. Girls grabbing you, fans chasing the bus after a concert... who was I, Michael Jackson or something? It was very bizarre, a life-changing experience.

“It actually hurt a little,” he continues, “because most people just knew Inner City. People didn’t know Kevin Saunderson the producer, even though tracks like ‘Rock To The Beat’ were being played in the biggest, baddest spots.”

Given that feeling, it might be surmised that the thoroughly underground E-Dancer project, which Saunderson debuted in 1991 via tough-as-nails cuts such as ‘Pump The Move’ and ‘Power Bass,’ was a reaction to the success of Inner City and a rewind back to his roots. Saunderson doesn’t see it that way. “It wasn’t really a reaction,” he says. By that time, the Inner City juggernaut had slowed a bit, “and I was finally home enough that I could dig in, dig deep, and get my internal musical emotions out into the instruments, and make music that’s made to be played in the darkest, deepest clubs.”

More than three decades on, Inner City still performs live; nowadays, the band features contributions from vocalist Steffanie Christi’an and Saunderson’s son Dantiez. (Another son, DaMarii, is also in the music-making business.) But following a steady stream of singles and the late-’90s release of ‘Heavenly,’ E-Dancer largely went silent.

“I felt like it was a weird time in music at least for me,” he admits. “Techno was going through a transition, and all the Europeans were coming up with their own kinds of sounds.” He specifically mentions trance. “The music kind of got lost. In my opinion, it lacked the groove and the feeling of its origins. There wasn’t much room for anything that was different, and even getting gigs became difficult.” Eventually, though, Saunderson decided to do something about it.

"Finally I figured it was time to start educating a new generation," he says. It was time to re-educate the clubbing masses — hence ‘Heavenly Revisited,’ ‘Infused,’ and, now, the remix album.

‘Re:Generate’ features a brand-new E-Dancer track as well, ‘The Rise’. It surges with the galvanic power of classic E-Dancer, and might be the best track on the album — which given the company it’s in, is saying quite a bit. It’s a foreshadowing of what’s to come.

“My goal was to finish ‘Re:Generate,’ try to educate some new listeners... and I’m actually working on a whole new album,” Saunderson reveals. “It might be a couple of years for that to happen, but it will happen.” In the meantime, expect an E-Dancer EP in the not-so-distant future.

Sweet Harmony

In summer of 2020, as protests for racial justice spread through the country, Saunderson was one of the voices decrying America’s lack of knowledge when it comes to the Black roots of dance music.

“America’s take on it,” he told Billboard that June, “was that this music was made by Europeans or white people only, and that Black people just didn’t touch it because it didn’t fit into R&B or hip-hop and didn’t have the same soul and feeling.”

It's a theme Sanderson’s quick to circle back to. “I look at a place like Space in Miami,” he says, “and a lot of DJs from Europe come there to play, because DJs from Europe are popular. Does that mean they are the best DJs or the best producers? No. I’m not saying they aren’t good, but there are plenty of American DJs and artists who are good as well! There’s a lot of talent out there, no matter what colour they are, but there should be some fairness.”

Saunderson holds out hope that the fairness will come to fruition. “There’s been, what — 35, 36 years of this music? It’s time for it to be one music and one race, with everybody together — the artists, the crowds, everything,” he says. “And if artists see that happen, that’ll help in the creation of their talents. That’s been my vision from the beginning, and I think it’s starting to actually happen,” he adds. “At least, that’s the hope.”

In the meantime, there’s work to be done. Besides new E-Dancer material that Saunderson has promised, another Inner City record is in the works, a follow-up to last year’s ‘We All Move Together’, with its title tune boasting a vocal turn from Idris Elba. A member of Hollywood royalty, even one who’s proved himself a credible DJ over the past few years, seems like an unlikely collaborator with a down-to-earth Detroit guy — but according to Saunderson, the hook-up came about easily.

“A friend of mine sent me a clip of Idris DJing ‘Big Fun’ at Coachella,” he explains, “and I was like, ‘You know, I think I want to work with him!’ We had already created ‘We All Move Together,’ and I had the idea of getting Idris to add some vocals to it. I just told my management and said, ‘Look, let’s reach out to Idris.’ We got connected, and he was like, ‘Wow, you want to work with me?’”

Of course Elba would jump at the chance — who wouldn’t want to work with one of the most important producers on clubbing history’s long timeline, especially one who’s still making music that sounds as good as ‘We All Move Together’ or ‘The Rise’? He might even find himself on the pages of an autobiography that Saunderson’s currently working on. “It’s my life story, my history in music, and all that’s connected with it,” he says.

Saunderson’s certainly got enough raw material to work with. “You know, when I was young, it was all about sports,” he says with a touch of wistfulness. “I want to play pro something: pro baseball, pro basketball, pro football, pro anything. So I definitely didn’t grow up with this vision of how my life would turn out. And that path I’ve been on has been for the better good. People come up to me and say how much the music touched them and changed their lives. When you hear stuff like that, you think, ‘well, this is the way it was meant to be’. As I would tell my kids, it’s good to have an idea of the path you want to take — but it might not end up that way. It can end up much better than you ever anticipated.”

And, of course, there are still plenty of tracks to be made and gigs to be played. “My passion is definitely just as strong as ever,” Saunderson says. “People don’t understand how I just keep going and keep going and keep going. But this is me.”