Meet Nhạc Gãy, the collective leading Vietnam's new era of electronic music

Georgina Quach discovers how Saigon crew Nhạc Gãy's homegrown sound, queer-friendly ethos and raucous raves are an antidote to tourist-centric nightlife in Vietnam

When Hanoian punk band Cút Lộn stormed the stage at Ho Chi Minh City club Arcan last June, a mosh-pit ensued. Red light bathed the screaming, four-piece outfit, dressed as high-school girls in Pikachu costumes. Frenzied partygoers rallied behind them, while an audience member in a vampire costume jumped onto the stage and lobbed a real sheep’s head over the crowd. Behind this explosive night was the Ho Chi Minh City collective, Nhạc Gãy. Nhạc Gãy is made up of five producers and DJs: co-founder and filmmaker Anh Phi Tran, art director Abi Linh (who DJs as Abi Wasabi), Celina Hyunh (who produces and DJs as km95), and Thao and Mike Pham. After Cút Lộn exited, Nhạc Gãy kept the blood pumping with DJ sets of techno, gabber, hard trance and hip-hop.

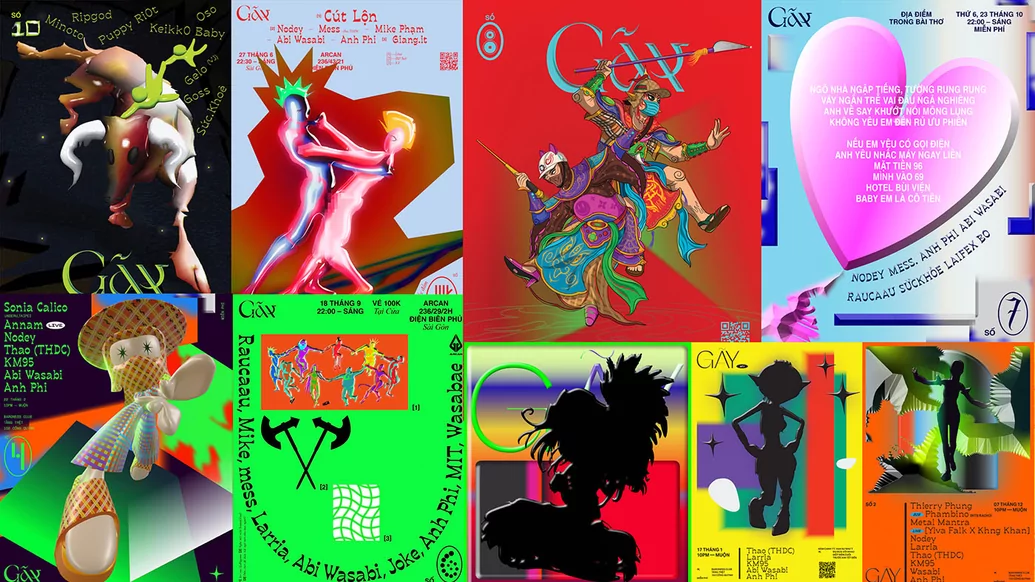

The rave not only marked the end of lockdown in Vietnam — where draconian policies halted COVID-19 early on — but also a cultural awakening within the country’s music scene. Rebelling against the foreign influences of Vietnam’s club scene, Gãy are driving a homegrown movement connected to Vietnamese identity. Saigon’s firecracker energy also gives their raves an edge; falling out of the club at 4am, you narrowly avoid the infinite flow of scooters whizzing by to grab a Bánh Mì (traditional sandwich) from the capital’s 24-hour street stalls. This new era for Vietnamese electronic music rings clear in ‘Nhạc Gãy Tổng Hợp Số 1’, a compilation released by Nhạc Gãy in February. Platforming local and diasporic Vietnamese artists, the 14 tracks feature banging breakbeats and deconstructed folk, with traditional Vietnamese instruments. Contributors include Puppy Riot, Nodey, Demonslayer and Anh Phi.

While there are huge obstacles for Vietnamese musicians — including a lack of finances, limited club venues and language barriers — the release casts a spotlight on their music-making which, for a long time, has been restricted to their bedrooms. “The Vietnamese electronic music scene has been freed, liberated and born to become the future of the next generation of local talents! I am so proud to be a part of this,” announces Kim Durbeck, a Vietnamese-Norwegian producer featured on the compilation.

For decades, Vietnam’s underground music scenes have been relatively muted compared to its richer neighbours. China, Japan, and South Korea have benefited from better infrastructure to support alternative tastes, which has fuelled more organised subcultures. In classic Communist tradition, Vietnam officially bans “offenses against the state” — an all-encompassing and ill-defined crime — and violations of custom, such as mannequins wearing underwear.

The government continues to monitor art exhibitions, films, TV shows and books. But with Vietnam’s recent economic growth, younger generations have become emboldened, with more disposable cash and disruptive ideas. Unlike established markets where the underground has become an industry in its own right, Vietnam presents a hive of opportunity for newcomers keen to ignite its nascent electronic, hip-hop and heavy metal scenes.

Also driving the momentum is the country’s frustrating lack of a nightlife market which treats locals fairly, says Kim. He explains that most clubs bring in foreign DJs, who headline festivals and clubs with a big fee guaranteed. Meanwhile, local acts are sidelined and receive much lower fees, or sometimes don’t get paid at all.

In recent years, the few underground music events available typically followed strict “only house and techno” policies and focused on attracting expats who could afford the entry fee. Vietnamese DJ and NTS resident Cuong Pham, aka Phambinho, describes this as “sính ngoại”, which loosely translates as xenophilia — with a peculiar disdain for what’s homegrown. “I know of people who have been kicked off the decks or out the clubs for violating the ‘standards’ of these gatekeepers.” This created a need for nightlife options which were open to niche, local sounds.

“Nhạc Gãy represents the first wave of alternative Vietnamese electronic club music born from oppression and a domination by the foreign market in Vietnam,” says Kim. He runs the Instagram meme account, Vietnamemes, which pokes fun at Vietnamese culture in a loving way. This aesthetic is playfully folded into Nhạc Gãy — Gãy’s poster by Hanoian artist Phạm Ngọc Thái Linh features the self-irony of Vinja “Vietnamese Ninja” women, motorbiking grandmas who wear bootleg designer gear.

Local events also offer a way to build a musicians network that is self-managed and sincere. Since Nhạc Gãy started five years ago, the non-profit platform has grown from throwing intimate parties in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City to huge gatherings with international DJs, becoming Vietnam’s primary launchpad for this exploration. News of an upcoming Gãy travels mainly by word of mouth. The parties squat in the sweat-soaked shadows of backpacker clubs and undisclosed locations that are constantly threatened by gentrification and police crackdowns.

“The Vietnamese government is very unpredictable,” says Abi Wasabi. “They can just come in and shut you down in minutes.” This is why the collective always secures the venue in advance, and releases the event location at the latest possible moment to keep numbers under control. One of their most recent raves took place in a hotel lobby, the address of which was coded in a Vietnamese poem on their flyer.

Seen as an affront to the Vietnamese state, raves which carry any political message are “too much of a risk,” says Abi. The conservative government hardened its stance on drugs after seven drug-related deaths at Hanoi’s Trip to the Moon festival in 2018. Despite this minefield of police raids and regulation, they’ve largely avoided run-ins with the Saigonese authorities since their first rave in October 2019. “The number one rule is don’t talk shit about the government,” she underlines.

Nhạc Gãy prides itself on being an assortment of rookies still learning from each other. In Vietnamese, ‘gãy’ means ‘broken’; their mission revolves around DIY forms of self-expression, however imperfect or nonsensical they turn out to be. It was “broken from its birth,” says Anh Phi. Having neither role models nor DJ classes to learn from, the crew pitched in to buy a controller and began messing around with it. They watched YouTube videos and picked up tips from the Arcan club owner, Goss.

In the early days, mistakes were common. Abi explains that whenever they made a wobbly transition, they would jokingly call it ‘gãy’. But that didn’t matter, and this haphazardness worked well with their favoured tempo and genre clashes. “To be honest, musically, it was messy, but we felt that it’s part of the spirit of Gãy. We didn’t want to be too purist, which can be the case in techno or house scenes,” says Anh Phi. Perfecting technique was far less important than playing diverse, adventurous sets that would surprise their partygoers, 95% of whom are locals.

The shutting of borders during COVID-19 encouraged the crew to pass skills on to budding DJs in their neighbourhoods. Nhạc Gãy’s performers and organisers work for free, and foregoing profits is a conscious choice. Without commercial pressures or expats to please, the assemblage they showcase — and their raves — can take on different forms.

That way of thinking resonated with the capital’s youth: Gãy’s raves became a melting pot for all kinds of generational, social, racial and gender identities. They dedicate their energy to creating a space where everyone can feel they belong. With giant balloons a favourite amongst Gãy crowds, the watchword is always fun. “It’s like a different world — just you, the music and dance,” says Abi. “You get to be yourself.”

While Nhạc Gãy avoid making loud political statements, breaking the silence on mental illness is urgent to the founders, some of whom have lost several friends to suicide. In Vietnam, where access to healthcare is precarious, mental health treatment is rare, expensive and stigmatised. Amongst creatives in the LGBTQ+ community, “it’s even harder to speak the truth,” explains Abi. This is why Nhạc Gãy started a podcast, InPsychOut, where they spread awareness and tackle taboos in collaboration with health professionals. “If no-one can help protect you, you’ve got to do it yourself.”

As its platform grows, Nhạc Gãy’s philosophy around “breaking” down societal norms — including mental health stigma — has never felt more important, for ensuring the Vietnamese youth feel a sense of belonging even after the sun comes up. All profits from the release of ‘Nhạc Gãy Tổng Hợp Số 1’ go towards a fund for Vietnamese mental health awareness.

Their mutual support and sensitivity for the local community has also helped them present their music and aesthetics from a non-Western perspective. “Whether it’s people doing karaoke, or playing Vinahouse (a local style which takes popular songs and amps them up to 140bpm) out loud or even just the sound of the street itself, sound is always present in Vietnam,” says Anh Phi. “I think this is really different and unique from the West.” Many of the producers on the compilation seasoned their tracks with sounds they grew up with, like ‘cải lương’ (folk opera) or ‘kèn ám ma’ (traditional oboe).

“In Vietnam, we all have this kind of love and patience for our heritage,” he adds. Kim’s track, ‘Nước mắm is my holy water’, takes inspiration from “falling asleep to his dad’s cải lương” at karaoke parties, combined with his love for 12-bit breaks and high tempo. “Somehow, the [childhood] musical aesthetics got stuck in my subconscious mind to one day be useful on a Vietnamese dancefloor.”

Thierry Phung, aka ONY, who performed at a Gãy rave with Phambinho, says sounds from childhood inspire his NTS Radio show. “Even without fully understanding the lyrics, as my Vietnamese has always been ‘gãy’; most of the karaoke songs my family and their friends were singing were crazy melancholic and nostalgic,” he laughs. “It’s like everyone was often getting really drunk and singing slow songs about how they miss someone or their country, or a time of their lives.”

This dialogue with the past enables Vietnamese creatives to imagine new possibilities for their future, where cultural traditions — lost, stolen, forgotten, neglected — stand as something to be cherished. “We are a fragmented community with a complex identity and history, so seeing local and diasporic Vietnamese coming together is incredible to witness,” says Thierry. Nhạc Gãy hope that the compilation will level the playing field, and bring together newly-found talent for their future raves. “I hope it will inspire the new generation to create and engage with art even more, and maybe find answers in the process.”