A space to be yourself: The rise of safe space parties

Creating a safe environment on the dancefloor is crucial for the mental wellbeing of all club-goers, particularly those from marginalised communities. Christine Kakaire speaks to the promoters and party starters creating safe space parties across the globe

In late 2015, the animated TV series South Park aired an episode called ‘Safe Space’. The phrase had been used in activist communities since the ’60s, but it entered popular culture in a big way that year, due to widely-publicised debates about student-led initiatives in North American and British universities. This escalated to the University of Chicago publicly discrediting safe space policies, and British actor Stephen Fry calling them “infantile”.

What were intended to be on-campus areas where students of marginalised identities could seek protection from violence and harassment, became shorthand, to some, for a hypersensitive and over-indulged generation. In typically skewering style, the South Park episode featured an original song: “If you do not like me, You are not allowed, In my safe space (my safe space) / Look and you will see, There's a very select crowd, In your safe space (my safe space) / People that support me, mixed in with more people that support me, And say nice things / Rainbows all around me, There is no shame in my safe space (my safe space).”

Depending on your perspective, the increasing prominence of the language of safe spaces may be a cause for celebration, confusion, ambivalence or derision. Even within dance music, where safe spaces have been in underground circles for decades, some recent, prominent responses to the term betray a pretty fundamental misunderstanding of its origins and purposes.

Two incidents in 2016 shone a light on this. Glasgow’s Sub Club declared the venue a “safe space since 1987” and were spectacularly dragged on social media, as female patrons and staff documented their experiences of harassment and assault in the club. Then, George Hull, co-founder of UK festival Bloc, issued a bitter missive through conservative-leaning political magazine The Spectator, saying that, “raves now aren’t worth promoting”. In his list of reasons, he included “the most depressing trend of all... the introduction of the ‘safe space’ policy”. His reasoning: codes of conduct, a supportive environment, and inclusiveness transform raves into “the opposite of fun”.

In viewing their own histories through rose-tinted glasses, both Sub Club and George Hull leaned on assumptive, shared experiences of the past. They didn’t acknowledge that even the headiest P.L.U.R. idealism of ’80s and ’90s raving was born of societies where people were treated unequally because of their perceived identities. The safe space clubs and parties of today have developed around these identities, centering marginalised perspectives and experiences as the default.

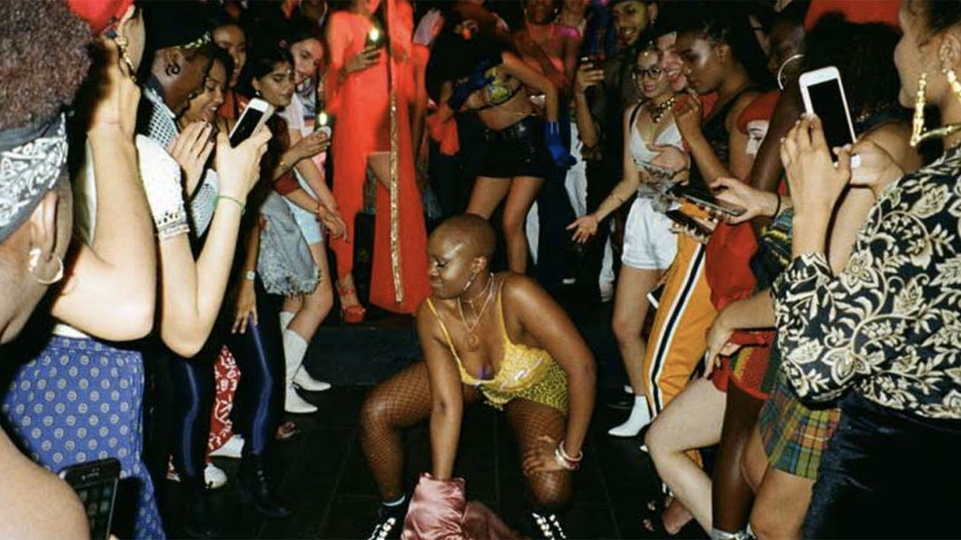

It’s also a truly international phenomenon. There are the queer and trans people of colour (POC) who gather each month to dance to merengue, voguing anthems and R&B at Papi Juice in New York, and the audiophiles and dancefloor introverts who seek a non-flashy nightlife alternative in Hong Kong club (Minh), where international guests Hunee and Prosumer have played. There is long-running Same- Sex Saturdays for Durban’s black South African LGBTQI+ clubbers and DJs, and Melbourne’s Cool Room, which aims for diversity across gender, race, sexual identity and physical ability at their house and techno raves.

It’s all bolstered by a global network of promoters, artists, DJs, and party-loving activists who believe that creating that ‘everybody’s free to feel good’ environment can only be achieved through clear communication of expectations, boundaries, and consequences. This is especially for the benefit of those that aren’t aware of how much of the outside world they’re bringing into a safe space with them. “Dominant power relations still find their way into the room,” wrote Malcolm Harris, in an article about the history of safe spaces for Splinter. “There’s virtually no way to create a room of two people that doesn’t include the reproduction of some unequal power relation, but there’s also no way to engage in politics by yourself.”

Transformative

Safe space clubs and parties do not want to — and cannot — create rooms that are sealed off from the societies that created a need for them. Instead, they try to remix the conditions of these rooms, so that individuals from (often intersecting) marginalised identities can get a clear shot at the kind of transformative rave experiences that should have always been available to them.

The organisers serve the needs of the party, not just the bar or the security. They make consensual, respectful communication a baseline expectation, advocate for the evolving language around gender and sexuality, and seek to minimise harm and violence. Safe spaces — or, more accurately, safer space parties — are utopian, sure, but that’s kind of the point. Most deliciously — and to the chagrin of curmudgeons like George Hull — safer space parties are a whole lot of fun. Colourful, bawdy, sweet, eye-opening, and hedonistic fun.

Safer space parties require a lot of careful thought. Above and beyond the usual thankless tasks of mainstream promoters and venue staff, a common thread is to incorporate education and outreach into planning and production. This was a steep learning curve for London-based artist Naeem Davis, co-founder of BBZ, an art and party collective for queer and transgender people of colour (QTPOC). A visit to San Francisco, where Davis attended the queer party Swagger Like Us, planted the seed for what would become BBZ.

“It changed my whole perception of what a space could look like,” said Davis. “This was the first party I went to where it was, very visibly, everyone and anyone. I’d only ever been to gay clubs in London, and I always had to compartmentalize my identity: I couldn't be black, queer, trans [all at once] — something had to be compromised.” The first BBZ party was in 2016, in a Jamacian restaurant in an area of South London that’s been reshaped by gentrification. With its intentional use of black and queer imagery in the promotional material, the party’s attendees suggested marking BBZ as a safer space event. “People just took [the artwork] as a statement of, ‘This is a safe space’,” says Davis. “The language evolved, we researched a lot of other parties and their rhetoric, and then slowly began to build our own.”

Those early days featured an art exhibit by DJ collective and NTS Radio hosts Born N Bread, and DJ sets from kindred spirit party Pxssy Palace, but after six months in the same location, a violent incident forced an abrupt rethink. “The 071 venue was half a restaurant, half a bar,” continues Davis. “Anyone could come in, it was just lucky that our crowd kind of policed themselves. But one night, six or seven young white men came in and started a huge fight. They were bottling each other. Police were called, it was terrible. The owner was like, ‘This a new business, I rely on the middle-class white people to come here’. So we had to compromise on the space and leave. But I always thank them for giving us the opportunity to do it in the first place.”

BBZ now has no fixed location, so Davis and the crew evaluate the challenges of promoting and running the party for each, individual space, while centring the enjoyment of their community. “We decided to make every party basically RSVP,” says Davis, “people had to direct message us. I don’t know how ethical this was, but we basically screened every single person. If somebody didn't have a mutual friend or identify in the ways of the people we centre, we would ask them who they were coming with.

“If we had a smaller venue, then we would ask them to maybe not come to this one, but another one where the capacity was larger,” Davis continues. “That changed the vibe of the party so much. Don't get me wrong, there are still issues within our community, [but] the dancefloor is not just a dancefloor. When you create a safe space, people bring everything to that room. All the bullshit that happens outside. I felt like a weight had been lifted in terms of not having to tell people who feel entitled to so many other spaces to leave.”

Social Inequality

The art of compromise has become a necessary element for Lölja Nordic, a Russian DJ and member of the intersectional feminist collective GRRR, who host safer space charity parties in different locations around Moscow. The party’s outspokenness against social inequality and discrimination brings an extra level of risk to their events. They react against what they see as state-sanctioned sexism and homophobia, including laws forbidding the distribution of so-called ‘LGBTQ+ propaganda’ to anyone under the age of 18.

A week before DJ Mag spoke with Nordic, the prominent Russian LGBTQ+ activist Yelena Grigoryeva was murdered in St. Petersburg. Her tragic death occurred just days after Grigoryeva spoke out with concerns for her safety, having found her name listed on a website that encouraged the hunting and killing of LGBTQ+ activists, inspired by the horror film Saw.

“Feminist and LGBT+ activists face a lot of threats on a daily basis here,” says Nordic, still shaken by the events of the previous days, “and you never know if it's a joke, or haters online, or if it will turn into real violence. A lot of events that have LGBTQ+ subjects can face problems. On the one hand, it's legal to do LGBTQ+ events when you have this mark, that it’s an 18+ event, [but] the police can come and start checking IDs because someone called them and told them that there are underage people here. There are a lot of haters who watch and check these kind of events to try to stop them.”

Along with the pressure of remaining vigilant about bad actors who may want to cause trouble, GRRR can also be troubled by venues and their owners. “It is important for us that people with mobility difficulties could get there [easily] and feel comfortable,” says Nordic, “but there is such a lack spaces without millions of stairs and tiny corridors. When you do find a space which is accessible and cool, it’s too expensive to rent or the owners are not interested in providing space for events with ‘political agenda’ — as they see it.

Even if the accessibility, rental prices and owners are fine, you may still face problems with the crew who works there. Not all of those people know what sexism is, what ableism is, what homophobia is. Often, people are not interested in these subjects at all. We have to communicate with the owners of the spaces, so they can prepare their crew about the event, but [even then], there is no guarantee at all that they will be respectful to the needs of the party.”

In some parts of the world, though, safer space club nights are helping to define the needs of communities who then build outwards, through advocacy and activism. Brazil’s QTPOC Batekoo parties were started four years ago in Salvador, the capital of the state of Bahia, by a small crew of Afro-Brazilians; the region has the highest density population of people of African descendants outside of the continent, but this was not being reflected in the city’s nightlife. “Salvador has a white elite,” says Artur Santoro, Batekoo’s projects director. “It’s a very white party scene, and very straight normative. A demand existed for a party made for black people, by black people.”

The popularity of Batekoo has far exceeded the original vision of a one-off birthday party for its co-founder, Wesley Miranda, which took on legendary status within Salvador’s queer Afro-Brazilian community. Since relocating to downtown São Paulo, Batekoo now also throws regular parties in Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte and Recife, laced with Baile-influenced beats, hip-hop and dancehall.

The crew has grown the original event into a platform which supports low-income black LGBT+ youth; it encompasses a record label, event production, vocational training, and a music festival. “The purpose of Batekoo,” says artist and record label manager, Eliabe de Freitas, “is to give back to the community and connect the community with the market. We have courses about everything that’s related to a night event — cultural production, soundsystems, DJing, lighting — so that we could hire them. And not only for us, for any kind of party. Inclusion — that’s what we need.”

It all comes back to one core message. “We have a spokesperson in every party,” says de Freitas, “saying the only rule that we have when she goes on stage and gets the mic: Respect.” Santoro agrees. “It’s a word that we always repeat. ‘Respect women, respect trans people, respect queer people, respect fat people, respect people with disability, and above all, respect black people. However you identify, you are in a party that has a black protagonism, so respect the black body here.”

When it comes to advocating for respect, and dismantling notions of respectability, nightlife culture also needs to better include the voices of disabled people. Laura O’Connell works in the disability sector in Galway, Ireland. It was her experience as a club DJ that sparked an idea for her accessible safer space club night, Bounce, catered towards the people she cares for. Before she started Bounce, O’Connell was hired to coach people with intellectual disabilities on how to DJ, in the lead up to Galway’s big social event of the year: a party called Tropicana.

“Before I came on board,” says O’Connell, “the DJs had been playing off iPads, or pre-made playlists. I brought in CDJs and a mixer, standard equipment. The students responded really well. It’s a lot more tactile, and they have more freedom when they’re using that equipment.” Seeing a demand for more regular events throughout the year, and a desire to move local parties out of dreary school halls and hotel function rooms, O’Connell thought about hosting a monthly night in a club environment. She found a willing venue in Galway venue Róisín Dubh, and Bounce has become a resounding success.

“It is a safe, accessible space, where they can socialise with their friends,” says O'Connell, of her Bounce regulars. “I suppose a lot of people have very good intentions of putting on these nights, but fear putting them on in a pub or a club. A lot of the time, people still treat people with intellectual disabilities like they want to put a bubble around them, really protect them from the outside world. Something that my team are very passionate about is these are young adults, like everyone else.”

Certain concessions have had to be made, though. The Monday night event finishes at 10:30pm to allow all attendees and their carers an easy journey home. “We really want to give them that experience, and it's worked out brilliantly,” O'Connell outlines. “We’re quite lucky that there's only one entrance and exit [in the venue], so you can keep an eye on people without invading their space, just letting them have a good time. The staff have been unbelievable. Obviously people can buy their own drinks and do what they like, but just making sure people aren’t going too overboard. We’ve been [going] for over two years and there hasn’t been any issue.”

Sexual Freedoms

As safer space parties evolve, new community nuances and regional needs will emerge. Berlin’s neon-splashed Room 4 Resistance collective has spent the last five years running “intersectional and body/sex positive queer raves”, which centres, “womxn, transgender folks, intersex, non-binary, black and POC folks, and asylum seekers.” Yet even in the context of Berlin nightlife’s famed open-mindedness, the collective is committed to holding additional space for under-served members of their community, especially when it comes to sexual freedoms.

Co-founder Luz recalls the decision to create a restricted dark room — in addition to an already established open-access dark room — specifically for women, trans, and non-binary individuals, with an entryway overseen by one of their awareness team members. “The reality is that if you have a dark room for everyone, very fast it’s becoming a cis male-dominated space,” says Luz.

“There is this idea that women don’t need dark rooms, that they’re not as sexual as men. My thought is, ‘How could we use them if we’ve never had this space?’ Also, they have often been unsafe for us, connected to sexual aggression and sexual violence. It’s not always easy for women or trans or non-binary persons to actually feel good in these spaces. The idea was even if no one is going to use it for a year, I would like that this space exists.”

The idea of a restricted, intentional space, inside a safer space party, has not been readily accepted by every attendee. “Some people would be angry: ‘I paid to get in the club, I need to access all parts of the club’. Did you access the office? No. Because there are some spaces in the club that are not for you,” Luz’s founding partner, Luis-Manuel Garcia, continues.

“[Dark rooms] are colonised instantly, from my perspective as a gay man,” says Garcia. “The base argument is pretty straightforward. Patriarchy is in there no matter what. Sometimes you just have to push it out. I think what is hard for a lot of cis men to get is that they can have the best intentions in the world, they can be the nicest guys, but their presence in a sexual space changes things.”

Where the South Park episode misses the mark — or perhaps hits the nail on the head, in its absurdity — is that it set up safer space isolationists and the camp horror figure of Reality as adversaries. Safer spaces are born out of broken social systems, but they remain closely connected to the mainstream. Like all of the events and collectives mentioned, Room 4 Resistance has taken up the invitation to leave its Berlin home base on occasion, collaborating with other collectives in other new spaces, and hosting showcases in new cities.

It’s a learning curve, but a necessary one: to introduce the transformative safer space project to new, imperfect places, rather than waiting around for the ideal venue. “Sometimes,” says Luz, “it is also the process of creating change. Only [taking R4R] to places that we already know about is not going to change anything.”

Reality may have crashed into South Park's safe space, but the real truth is that, like it or not, safe spaces are now a part of our clubbing reality. With more resources available now than ever — to seek out like-minded individuals, hone in on precise music tastes, and create communities — it’s inevitable that mainstream rave culture will have to make space for the voices of those who have, for too long, been stuck on mute.