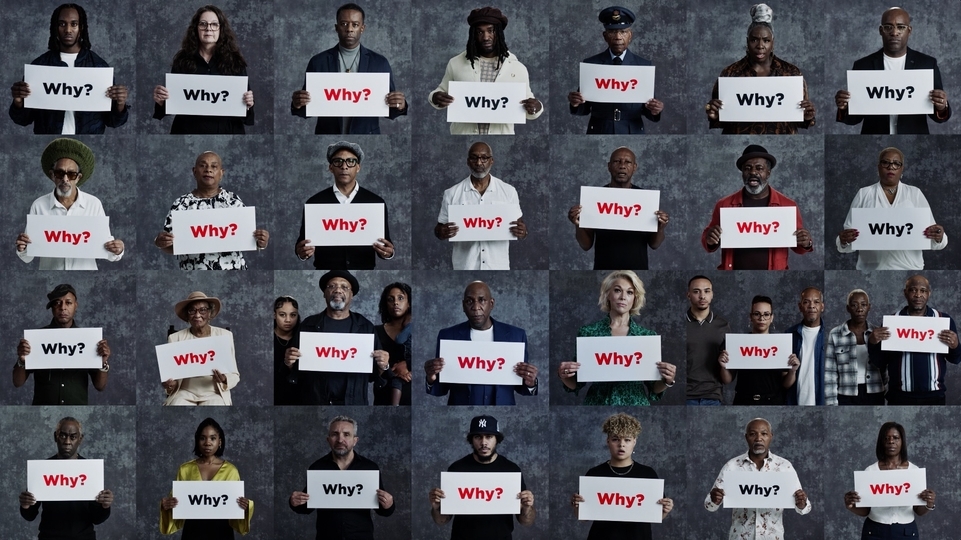

Children of the Windrush Generation: the pioneering DJs who paved the way for UK dance music

Some of the most important DJs in the development of the UK scene are children of the Windrush generation. DJ Mag's editor-in-chief, Carl Loben, speaks to Black and mixed-race foundation DJs about their parents, racism, culture, and being pioneers in our beloved scene

This feature was originally published in 2018, at the height of the Windrush scandal, and on the 70th anniversary of the Windrush ship's arrival in the UK

Seventy years ago this month, the Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury near London carrying passengers from Jamaica in the Caribbean, and a number of other countries. An advert had been placed in a Jamaican newspaper offering cheap transport to the UK for anyone who wanted to go to live and work there, and just under 500 people took up the offer. The British Nationality Act of 1948 had just been passed, giving citizenship to ‘British subjects’ from commonwealth countries — former British colonies — and a number of Black servicemen who had fought for the Allies in World War Two also decided to make the journey to the ‘mother country’.

The British government encouraged immigration from commonwealth countries, because post-World War Two labour shortages meant that they needed people to work in the newly-created National Health Service, on the rebooted transport networks and so on. This influx of newly nationalised men and women who followed from the Caribbean in the subsequent years became known in the UK as the Windrush generation.

All well and good, but what’s this got to do with DJ Mag? Well, it just so happens that some of the children of the Windrush generation played a hugely significant part in building the UK dance scene — just as their parents had helped bolster the post-war infrastructure. Lately though, as anyone who follows the news will know, some older folk have been caught up in the current government’s ‘hostile environment’ policy which has, disgracefully, led to people being deported or not allowed to access the NHS after living, working and paying taxes in the UK for forty or fifty years, or more.

It’s a shameful episode in recent British history, one that has developed while writing this piece — claiming the scalp of former Home Secretary Amber Rudd, caught out lying to Parliament about immigration targets. But we want to celebrate the immense contribution of some of the Children Of Windrush – Black and mixed-race British DJs who helped build our electronic music scene.

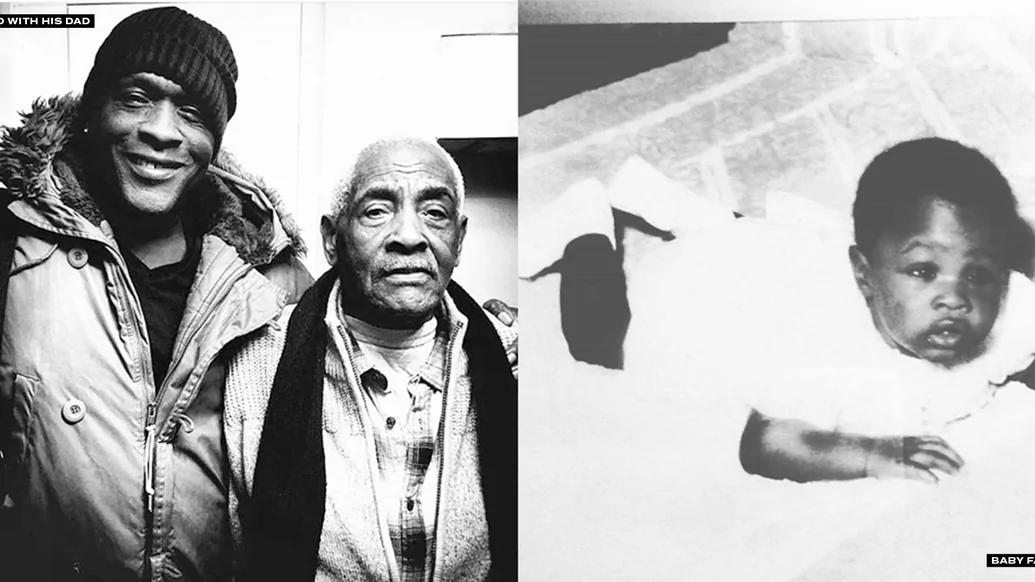

“My parents came in ’55 and ’56,” says music legend Norman Jay MBE. “They didn’t come on the Windrush itself but they came from [Caribbean country] Grenada. They both ended up living in Notting Hill, funnily enough, and working in and around northwest London.

“My dad was a grade one civil engineer on London Transport, having worked his way up from going to night school and getting all his certificates,” Norman continues. “My mum did various manual jobs, and then she became a childminder.”

“My dad came over in ’56, and then he sent for my mum,” says Bristolian junglist, Roni Size. “They were together already, but couldn’t afford to come at the same time.” Roni’s immediate family ended up in Bristol, his mum working in the local hospital and his dad in the local Cadbury’s factory and as a builder. He remembers as a kid extended family coming from Nottingham, Birmingham and London for family gatherings.

“Both our parents are from Jamaica and arrived in the UK in the 1960s,” say drum & bass pioneers Fabio & Grooverider, who were awarded the Outstanding Contribution gong at DJ Mag’s Best Of British awards in 2015. “Both of our parents worked in the transport industry and were brought over to help rebuild the country.”

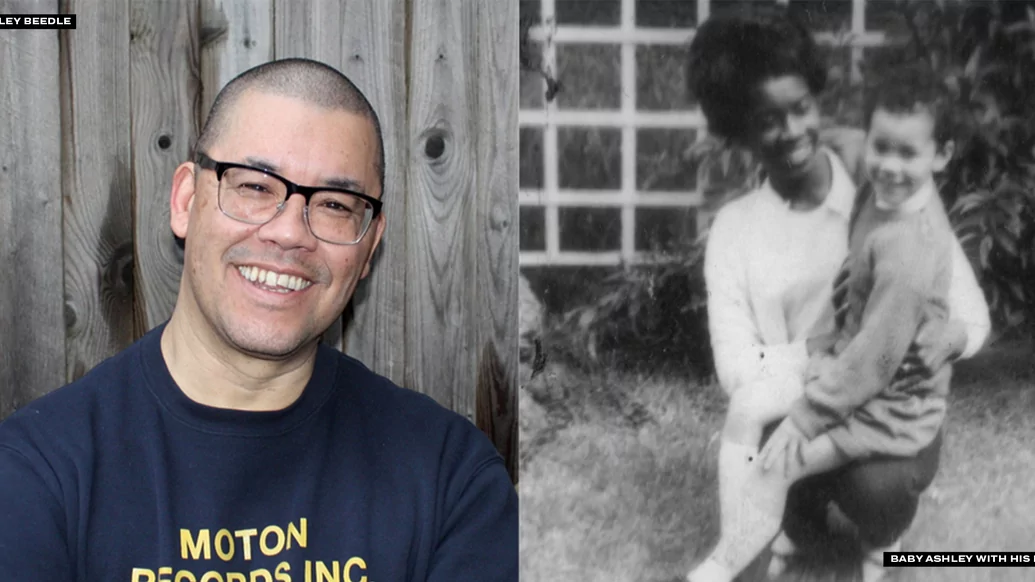

“My mum arrived from Barbados in November 1960 and went straight to Leavesden Hospital in Hertfordshire after landing at Gatwick,” UK house music pioneer Ashley Beedle explains. “The matron put her straight onto the ward without any training and nicknamed her ‘Topsy’ — she was never called ‘Nurse Layne’! She met my dad, who was a hospital porter — he sported a blonde quiff and rode a motorbike. Allegedly, my mum became the first Black ‘ton up’ girl when my dad took her up to the famous Ace Café on the back of his motorbike!”

‘Ton-up boys’ was the name given to rockers who rode their motorbikes past 100mph, but Ashley’s mum would experience racism from both the UK and Barbados for marrying his white rocker dad. “When they married, the local and national newspapers came and reported on the wedding, as a mixed-race marriage was so rare,” Ash says.

Ashley was born in the UK in 1962, and his family moved to Barbados when he was seven months old. “My mother experienced racism from other Bajans and from white officials too,” he explains. “Barbados was still a Crown Colony and didn’t gain independence until November 1966. My mother couldn’t accompany my father to social functions; she couldn’t gain access to any white members-only bars and clubs, and as a couple they would be stopped and questioned by the police. As a result, we moved back to the UK after three years and settled in Harrow.” London had its own share of racists at the time, though. “Racism was the norm,” says Ash.

The Windrush generation may have been invited to the UK from the Caribbean to help rebuild the country, but most could scarcely anticipate the appalling level of racism they would experience on arrival.

“My mum and dad are both from Guyana originally, which is considered part of the Caribbean due to strong cultural links,” says jungle stalwart Jumpin Jack Frost (real name: Nigel Thompson) down the phone-line to DJ Mag. “When did they arrive in the UK? Let me just put my mum on the phone, one second...”

Frost’s mum Ingrid comes on the line. “I arrived in June 1961, I think Nigel’s dad came the year before,” she begins, explaining how she ended up living in Brixton. “Did I experience racism in my early days here? Oh yes, yes. There were situations where you’d see a job advertised, you go for the job, and when they actually see who you are then suddenly the job’s gone. That sort of thing.

"And at school there was a lot of name-calling," Ingrid continues. "The way the children got treated at school was also an issue — because they were Black, they were treated in a certain way, put into certain streams. But later on I found that people whose children had been told ‘You will never make this, you will never do that’ have turned out to be doctors and lawyers and all this sort of thing.

“For a lot of Black people who came here, their original idea was that you were gonna spend five years here and then go back,” she explains. “But in reality you get into relationships, get married, have children. We came over to get a better life, but we found a lot of things where we thought, ‘Oh dear, is this better?’ When they get into financial difficulties, they always try to blame ‘the people who have come here and taken our jobs, taken our houses’.”

“I was thinking the other day about the Commonwealth, and when you think about it, it’s 53 countries that England colonised. When you think about it that way, it’s a disgrace” – Jumpin Jack Frost's Mum, Ingrid

It’s an absolute pleasure talking to Frost’s mum — who doesn’t really like the term ‘Windrush generation’ herself — and after a while she moves onto the history of slavery; an appalling episode in Britain’s history. “Initially it was from Africa, and they were forcibly taken to these places like the Caribbean,” she says. “I was thinking the other day about the Commonwealth, and when you think about it, it’s 53 countries that England colonised. When you think about it that way, it’s a disgrace. A lot of these things that were built up — the cotton industry, the mills and all that — was on the blood of Black people. The sugar industry... all this money coming from the colonies.”

Norman Jay talks of how his mum and dad lived on eight or nine streets around the Notting Hill area — within a mile of the Grenfell Tower when it was built later on — in quick succession in the late ‘50s. “My mum said that every four to six weeks they were getting evicted or chucked out and forced to move,” Norman, who is currently writing his memoirs, says. This was an era when signs saying things like ‘No coloureds’ or ‘No Irish, no Blacks, no dogs’ frequently appeared in the windows of properties to let.

In the late 1950s in London, white working class teddy boys would frequently racially abuse Black West Indian migrants in Britain. Fuelled by the scapegoating rhetoric of far-right groups like Oswald Mosley’s Union Movement, peddling claptrap like ‘Keep Britain White’, there were a number of violent attacks on Black people in west London in late August 1958 — leaving at least five Black men unconscious.

After an incident where some teddy boys assaulted a mixed-race couple (Raymond Morrison and his white Swedish partner Majbritt), approximately 300 teddy boys began rampaging through Notting Hill armed with iron bars, knives and belts — breaking into homes and attacking any West Indian they could find. The shocked Black community was forced to fight back in self-defence.

The ‘racial riots’, as the press called them at the time, continued for several days over the August Bank Holiday weekend. Senior police officers tried to dismiss the riots as “the work of ruffians, both coloured and white” hellbent on hooliganism, but secret police papers released 44 years later stated that they were overwhelmingly the work of a white working class mob, out to get members of the Black community at the time.

“My parents lived two or three streets away from where that whole 1958 race riot kicked off,” remembers Norman Jay. “My dad had to run the gauntlet, trying to avoid those gangs of teddy boys. Harrowing stories.”

“My parents lived in Notting Hill before I was born, and when the riots happened they moved to Hampstead,” says DJ and singer Rhoda Dakar. “The race riots of ’58 made them move.”

Rhoda’s dad first came to the UK in 1923. He’d fought for the British in World War One before being shipped back to Jamaica, she says, and lived quite a nomadic existence around Europe, spending time in Paris and becoming immersed in the jazz scene. “In 1938 they knew war was coming, so they started ejecting all the foreign nationals, and he had to come to the UK cos he was British,” Rhoda says. “Because he’d learned French, in Paris, he said ‘I spoke fluent French, so I was a Frenchman. Then when I came to England, I was just another black man’. Which is an indictment really.”

In response to the west London riots, a Caribbean Carnival was held early the following year to celebrate West Indian culture — the precursor to the awesome annual Notting Hill Carnival, which now attracts over a million revellers every August bank holiday weekend with its parade of floats and renowned soundsystems.

Norman Jay, of course, would have a long association playing Carnival over the years, turning many young people onto house music and other styles for the first time. “Over 30-odd years I’ve successfully managed to integrate 10,000 people at my Good Times soundsystem at Notting Hill — the mixture of people was like a proper Coca Cola advert, y’know?” he says. “That’s what I’ve always strived to achieve.”

The Black migrants who came to the UK from the Caribbean in the ’50s and ‘60s brought with them a rich cultural heritage. Norman Jay remembers family celebrations where extra speakers would be plugged into the radiogram and aunties and uncles would bring records, while Roni Size talks about his dad’s “prize collection of seven-inch records, about 20 records which they’d play on rotation”, especially recalling tracks like the rocksteady heavy monster sound of ‘Monkey Spanner’ by Dave & Ansel Collins, and calypso cut ’Shame & Scandal In The Family’.

“Our families brought culture, which is now in the fabric of British society. The swagger, the language, the mindset... the thing about the musical influence was, my parents listened to Elvis as well" — Roni Size

Roni chats fondly about one of his uncles who had a pure calypso record collection. “Everyone had a gramophone in their house, you’d stack up all the seven-inches on it and they just came on one after another,” he smiles.

“Our families brought culture, which is now in the fabric of British society,” Roni continues. “The swagger, the language, the mindset... the thing about the musical influence was, my parents listened to Elvis as well. And Pat Boone, but then they’d also listen to The Mighty Diamonds. It was more the celebration — like with Carnival. The main thing that the Windrush generation brought here was the Jamaican spirit. And white rum.”

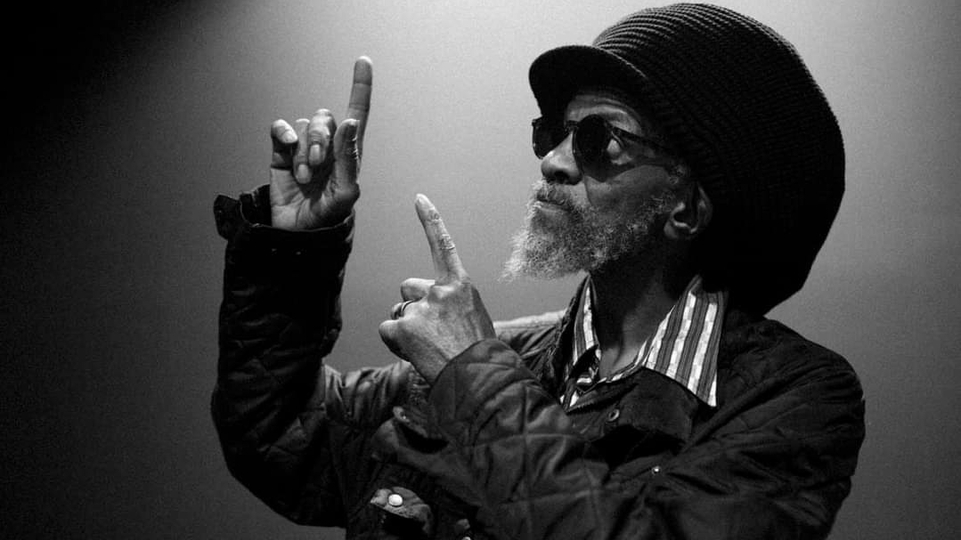

Jumpin Jack Frost tells DJ Mag about growing up around his uncles who were into a lot of funk and soul, and then experiencing the Jah Shaka Soundsystem — “skanking, being really heavily into it” — before becoming a box boy for Frontline International, “helping to lift the [speaker] boxes and the wires into parties”. His recently published autobiography, Big Bad & Heavy, goes into fascinating detail about his trials and tribulations growing up around the music scene in London.

Soundsystem culture originated in Jamaica in the 1950s, when DJs would load up a truck with a generator, turntables and huge speakers and set up street parties. It was actually the ‘DJ’ who would rap over the tunes while the ‘selector’ picked the tracks, and as time went on crews began cutting dubplates so that they’d have exclusive original sounds — a precursor to how drum & bass would operate several decades later.

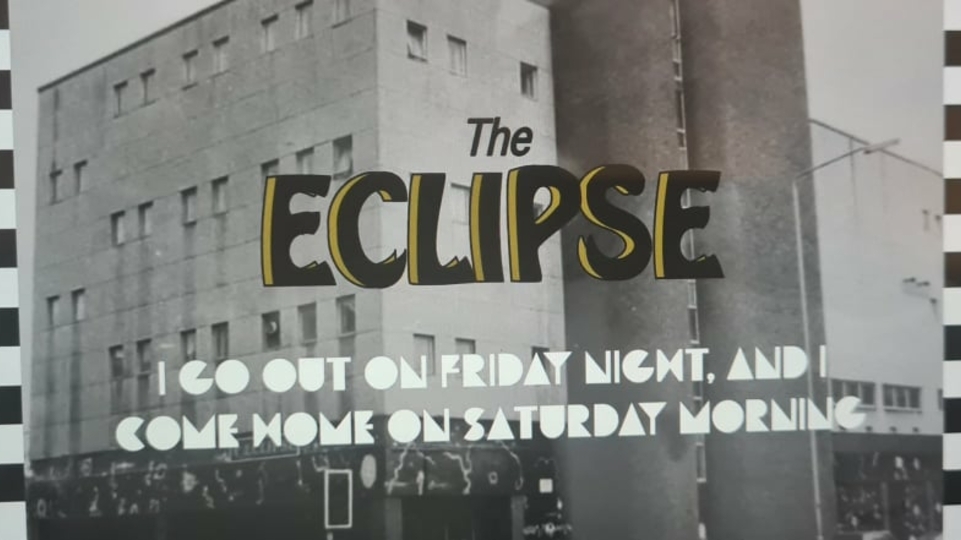

After the continued migration of Caribbean people to the UK in the 1960s and ’70s, a plethora of soundsystems emerged in most major cities where there was a Black community. Basements were commandeered, and illicit blues parties would provide these systems with a homegrown DIY dance space to play styles like ska and reggae. Segueing with the growth of discotheques into nightclubs, soundsystems were crucial to the development of UK dance music.

“When I went to my first proper nightclub I met like-minded people who looked like me, loved the same music as me, dressed like me,” reminisces Norman Jay, “it was paradise for me at the time. I’m talking about the early 1970s to start with, at clubs where Black people could celebrate their music. Most clubs wouldn’t let Black people in, but I discovered places where Black, white, straight and gay mixed happily and enjoyed the music that we all loved.”

“Most clubs wouldn’t let Black people in, but I discovered places where Black, white, straight and gay mixed happily and enjoyed the music that we all loved" – Norman Jay MBE

“I used to go to St Gabriel’s Youth Club in South Harrow around ‘78 on a Sunday, and was immersed in the soul/jazz funk/disco scene,” says Ashley Beedle. “However, when I was part of a group of four or more Black guys, we were usually turned away at certain club doors — there was a colour bar even though they played Black music!”

Ashley did his first gig at 16, and started DJing at blues parties before joining Stateside Sound System as a box boy, then Shock Sound System with the Zepherin Brothers — Dean and Stanley — Cecil Peters, Ricardo De Force and Paul Denton. “We DJ’d together at Notting Hill Carnival in Powis Square, and we were the first Sound to play house music,” he recalls.

Enoch Powell delivered his inflammatory Rivers Of Blood speech in 1968, but on dancefloors and at gigs Black and white people were uniting through music. Disco and punk were the predominant sounds of the late 1970s, although punk — unlike disco — was pretty white, in the main. “I talk to Don Letts now and he says, ‘It was you, me and the doorman’, but there was more Black faces at The Roxy than that,” Rhoda Dakar tells DJ Mag. “I may have known most of them, but there was still no judgement about it.”

Don Letts — whose parents were from Jamaica originally — was the hugely influential DJ at punk haunt The Roxy, playing dub reggae in between the punk bands. His sounds unwittingly spawned a ‘punky reggae party’ whereby subsequent post-punk bands filled their sound with more space, and acts like Big Audio Dynamite — who Letts featured in, alongside Mick Jones from The Clash — set out exploring a dubwise beats sound.

The ska-tinged 2-Tone sound was the principal band-centred youth music movement after punk. The two Black guys who flanked deadpan singer Terry Hall in The Specials — Neville Staple and Lyndal Golding — were Jamaica-born, and the multi-racial nature to 2-Tone (bands like The Beat, The Selecter, etc.) helped change a lot of previously racist attitudes amongst white working class youth — as had Rock Against Racism a couple of years before.

Rhoda herself joined The Bodysnatchers, ending up in Jerry Dammers’ The Special AKA a few years later — recording ‘The Boiler’, a song about a rape victim, and singing on the influential ‘Free Nelson Mandela’ track in the mid-’80s.

2-Tone did still attract its fair share of boneheads. “Mate, I stood on the stage in Guildford with a good half of the audience ‘sieg heiling’ at me,” Rhoda recalls, when The Bodysnatchers were supporting Madness. “The rule was, they start ’sieg heiling’ and we stop playing and walk off stage until they stop. We downed tools, and they didn’t stop, so I had to come on and shout at them until they stopped and then we could carry on with the gig.

“Did any neo-Nazis have their minds changed by the multi-racial element of 2-Tone? Some of them did,” Rhoda continues. “I used to spend a lot of time talking to people in the audience before or after we went on, and used to get told off by the promoter. But it did used to change their minds. With the best will in the world, it’s pack mentality — these people aren’t mental gymnasts who’d thought it out, at that age it’s about outside influences, not people who are thinking for themselves.”

Simultaneously at the turn of the 1980s, Kool Herc — who’d emigrated from Jamaica to The Bronx, NYC when he was 12 — is credited with being the founding father of hip-hop by cutting up instrumental breaks on two turntables and for his syncopated speaking on the mic. He too was influenced by Jamaican soundsystem culture.

Hip-hop gradually got huge through the ‘80s in the US and internationally, and the credible UK version was kick-started by the London Posse in the late ‘80s. Unlike most UK hip-hop acts up until that point, the London Posse refused to rap in fake American accents. Rodney P, himself of Caribbean origin, and cohorts instead used their London vernacular, in turn laying the groundwork for grime 15 years later.

Soundsystems would often provide the amplification when acid house parties first came along. A young Carl Cox, whose parents had come to the UK from Barbados, had his own soundsystem in the ’80s, which he lent to the first two Shoom events — the Danny Rampling-fronted club-night that was instrumental in kicking off the UK’s late ’80s acid house boom. Not sure quite whatever happened to that Coxy fellow... (clue: he became a global ambassador for our scene).

Soul II Soul were also a soundsystem to begin with, and their dances at the Africa Centre in London’s Covent Garden — a huge influence on Jumpin Jack Frost, and many others — provided a bridge from soul, funk, hip-hop and reggae into house music. Soul II Soul were fronted by funki dread Jazzie B, whose parents originally came from Antigua in the Caribbean, and their multi-racial party nights helped set the dance scene up to be a welcoming place for all loving races.

Before the so-called first Summer Of Love in 1987, clubbing was dominated by funk and rare groove — the latter a term coined by Norman Jay himself, who had been throwing his Shake ‘N Fingerpop parties since the early ‘80s. “For many people, 1987 was Year Zero,” Norman says. “For my generation of DJs, we looked at that and smiled, cos our dances had been around a decade or two prior to that. So for me, I saw it coming, I embraced it, I loved it and I enjoyed it for what it was, and was grateful and thankful to have been part of it.”

“Acid house was a multi-cultural explosion, it was a time of change,” says Jumpin Jack Frost. “We had people from all backgrounds and cultures coming together and becoming friends.”

DJ pioneers like Fabio and Grooverider got swept up in the rave revolution, and when they took a residency at Rage at Heaven in the early ‘90s they inadvertently helped create drum & bass with their mash-up sets of breakbeat hardcore, jungle tekno, sped-up hip-hop and bonus beat house rhythm tracks — speeding up tunes and chopping up breaks.

Goldie — whose dad was Jamaican — used to go to Rage with his girlfriend Kemistry and her best mate Storm, and made it his mission to make a record that Grooverider would play at the club. ‘Terminator’ was the result, a game-changing track using time-stretching techniques that helped shape the future for drum & bass — a scene chiefly built by a whole gaggle of ‘children’ from the so-called Windrush generation (Randall, Fab & Groove, Frost, Bryan Gee, LTJ Bukem, Roni Size, Brockie, Goldie, Congo Natty, Ray Keith, etc.). Without these foundation DJs, there would be no drum & bass scene whatsoever.

From Trevor Nelson and his smooth R&B grooves to cats such as Matt ‘Jam’ Lamont, Karl ‘Tuff Enuff’ Brown and Norris ‘Da Boss’ Windross birthing UK garage, first lady of ‘90s house Smokin’ Jo to Imagination’s Leee John in disco-funk and many more, the influence of many Children Of Windrush in building the UK dance scene is immeasurable.

All the above-mentioned DJs hold British passports and have travelled in and out of the country numerous times DJing internationally. Most of their parents — if they’re still alive — have British passports too, but some, including thousands of the Windrush generation who came to the UK on their parents’ passports, have been caught up in Theresa May’s ‘hostile environment’ policy. This was where, under pressure from UKIP and right-wing papers like the Daily Mail and Daily Express, the Home Office changed the methodology for ‘catching out’ illegal immigrants.

Anyone coming into contact with the NHS, employers and landlords without all their papers intact was suddenly almost criminalised — the onus was on them to prove they were not illegal immigrants, even though they’d maybe lived and worked in the UK for decades. Just before DJ Mag went to press with this article, it was revealed that at least 63 Windrush generation people had been wrongfully deported on Theresa May’s watch. Scores had been sent to detention centres, and literally thousands more have been worried sick by unwanted — and unwarranted — hassle from the authorities. Not so much a scandal as a complete and utter outrage.

“My mother is finding it increasingly difficult to navigate her way through the NHS,” says Ashley Beedle, who’s had a slew of big club records over the years with X-Press 2, the Ballistic Brothers and Black Science Orchestra. “She is getting constantly asked about her nationality and her tax status — which she paid for over 40 years in the UK! It’s insulting and depressing, and not something I’d expect her to have to put up with in 2018.”

“I’m worried about my dad, cos my dad didn’t apply for citizenship, so this is something we’ve got to go through, to make sure he has his proper papers in order,” explains Jumpin Jack Frost, who is now also involved in the Save Our Boys & Girls mentoring scheme for at-risk young people in London. “He’s been here since 1960, you know what I mean? It’s his home. This is something myself and my sisters and brother are looking to sort out for him. And it’s disgusting that we have to think about this at this point in his life — he’s over 70 years old. For him to have to worry about this is not on.”

Frost tells DJ Mag that he’s shocked by this Windrush Scandal. “We shouldn’t have to be worrying about our parents after all the contributions that they’ve made to this country,” he says. “We shouldn’t have to worry if they’re gonna be kicked out — and some people have lost their jobs over this, some people have already been deported.”

“I’m no expert, but I remember a couple of years ago they started deporting people who were originally from Jamaica,” says Roni Size, who won the Mercury Music Prize in 1997. “They ‘dipped’ everyone. I look at my family pictures and I think: ‘We were lucky’."

“My parents were British citizens before they came here, so they didn’t need to apply for anything — why should they?” says Norman Jay, who was made an MBE in 2002 for services to music. “They were invited. But the British government has always tried to muddy the waters with that, which is why they conveniently destroyed all those landing cards.”

“In the community we’ve always known about cases like in this Windrush Scandal — it’s just that now you guys have discovered it,” Norman continues. “My parents have been saying it since the 1950s, it’s nothing new. It’s appalling, and it’s great that we’ve got MPs like David Lammy, the Labour MP, calling it out and standing up to it, he’s one of the few voices we’ve got at that level to directly challenge the government on that, cos like Stephen Lawrence, like Grenfell, the community won’t let go. We will hold them. They’re on a sticky wicket now cos they’re in the public glare.”

It’s thanks to the work of Guardian journalist Amelia Gentleman and others that Windrush cases have been in the public eye of late. In one instance, Hubert Howard was struggling for 13 years to prove to the Home Office that he was in the UK legally — having arrived in 1960, aged three, with his mother. Unable to obtain a British passport, he lost his job, was denied benefits, and couldn’t visit his mother in Jamaica before she died. He asked if Amelia Gentleman could sit in on his review meeting with the new Windrush taskforce in early May, and his application was successfully processed in 45 minutes.

For Rhoda Dakar, now a patron of the Music Venues Trust, the whole Windrush Scandal is just the tip of the iceberg — and that’s before Brexit has even kicked in. “If Canadians can be thrown out, what’s going to happen to Indians and Pakistanis? What about all the people who came here from Uganda?” she asks.

“It’s immeasurable what people have put in, and everything we have to describe the music today is almost directly coming from the Windrush generation or the people who came before to fight in the two world wars and stayed,” Rhoda adds.

The evolution of most major music genres begins with different forms of Black music, and the dance music scene as we know and love it today wouldn’t exist without the Windrush generation migrating to the UK. They worked hard to help rebuild the country, often facing terrible racism along the way, but enriched UK culture immeasurably. In turn, many Children Of Windrush made (and continue to make) an immense contribution to building the UK dance music scene — salute!