At Home With: Melvo Baptiste

Music director of Defected’s Glitterbox brand, boss of The Remedy Project, radio stalwart and more, Melvo Baptiste brings a healthy dose of the soul to everything he touches. Ria Hylton visits him at home in Watford to rummage through his extensive record collection, hear about the influence of his soul boy dad and uncle Norman Jay MBE, and find out why Notting Hill Carnival holds a special place in his heart

Melvo Baptiste bridges generations. His musical lineage reaches back to UK sound system culture and the dancefloors of New York legend, all the way up to our contemporary soulful scene. The DJ, producer, label head, and newly crowned music director for Glitterbox got an early start, having been raised by soul heads, but he’s also put in the work building relations with up- and-coming talent, while paying respect to those he feels never got their moment to shine. You see this in his interviews with artists on his Remedy Project imprint, keen to tease out the cultural impact their work has had on the scene. “You brought out ‘African Warrior’ and changed everything,” he tells Donae’o, noting the influence that track had on Black British music. “As present as you are, you’ve also managed to stay underground in what you’re doing,” he tells T.Williams, a producer who’s touched many areas of dance music, but flown under the radar for most of his career.

When we finally locate his apartment in Watford, Baptiste is laid back in his L-shaped sofa, in an orange cap and Aaliyah print t-shirt. He stands tall and greets DJ Mag with a bear hug before settling back into the sofa’s corner, framed by classic prints of Larry Levan at Paradise Garage. “My dad’s a soul boy through and through,” he explains. “He was a dancer on the scene, told me all the stories and it sounded beautiful.” From Detroit’s Motown and the Georgia roots of funk via James Brown, to the Philly Sound and, of course, the fashion, Baptiste was well-schooled in the soul boy ways.

Those weekends spent listening to his dad’s collection have formed the bedrock of his musical education. In fact, his dad’s still teaching him. “Even now that’s all he wants to talk about,” he says. “There’s a group on Facebook called ‘Soul Boys, Soul Girls’ and he just posts relentlessly — his knowledge is insane.” Baptiste nods towards wooden crates full of 7” records underneath his DJ booth, a gift from his dad. “We did this little party together and he left me the two boxes, hasn’t mentioned it since.” Has he forgotten, we ask, or is he gifting them but doesn’t want to talk about it? “Exactly that! Don’t get me wrong, he’s got a lot more precious boxes that he wouldn’t dare let me have, but yeah he seems to have freed those ones up a little bit.”

And then there’s his uncle Norman Jay (MBE), who launched the rare groove movement and illegal warehouse parties — a precursor to the acid house scene. Melvo was too young to catch Jay’s early KISS shows, but by the late ’90s, every Sunday the Baptiste household would turn off the TV and tune into Jay’s three-hour show on BBC London Radio. “Hearing your uncle's voice coming through the radio — that was huge.” And as he got older, Baptiste would sit in on Jay’s shows at the BBC studio, soaking in radio culture and learning his uncle’s particular style up close.

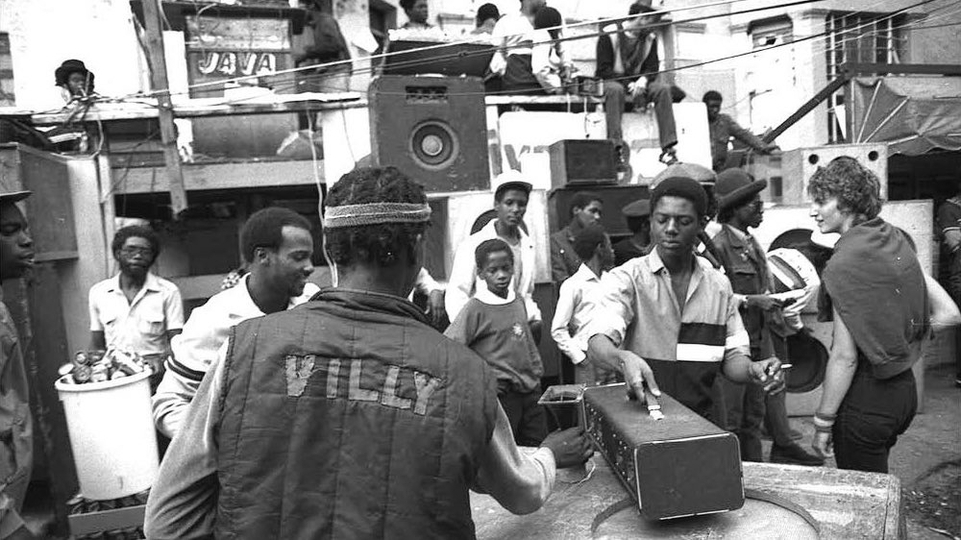

It was at Notting Hill Carnival, where Baptiste got to see Jay work the crowd at the now legendary Good Times sound system spot, on the corner of West Row and Southern Row. A faithful presence at Carnival since 1980, this street party was the reincarnation of Jay’s earlier parties, consciously bringing crowds who might not mingle in real life onto one dancefloor. “Norman really knew how to play to that crowd,” Baptiste remembers. “He’s one of the only guys I know that can seamlessly go between a drum & bass record into House Of Pain, into something of cultural importance — Public Enemy ‘Fight The Power’ — then play another ska record. You were just with it for the journey.” It was a slog in the sound’s early days though, pushing against the narrow musical lanes in sound system culture at the time — Jay’s older brother once had to rescue him from roots heads unhappy with the soul tracks he was playing.

His involvement in sound system culture early on shaped not only Baptiste’s musical tastes, but also his appreciation for those dancefloors that inspired his uncle — Jay visited Paradise Garage throughout the ’80s. He plays Paul Kelly’s ‘Believe I Can’, a super sweet B-side, as an example. “They would play those records in the middle of a set and it was fine — now in clubs everyone’s scared to change the tempo,” he laments. “People think DJing is about tight mixing and what’s the biggest, most well-known record you can play, but it’s not about the mix — the technical stuff — it’s about your selection. Back then it was just about raw selection.” Baptiste got his first training at Mi-Soul Radio, plugging away at weekly two-hour shows for the best part of seven years. Saturday mornings 11am-1pm. Witnessing Jay for as long as he had gave him a foundation and provided ample room for imitation, but soon enough he’d locked in his own style and musical calling, pushing contemporary acts in the UK’s neo-soul scene.

“I adore radio, it’s my first love,” Baptiste tells us. “If I could only keep one, I’d keep radio.” Why? “When you’ve done all your prep all week, the last show is finished and you jump on, put your headphones on, push the fader up, and the studio goes dead silent and it’s just you and the listeners — that feeling, I just love it.” It was in 2016, while Baptiste was lying on a beach in Thailand, that his new career began. A message from Defected’s booker came through, asking the DJ if he’d like to play their first Glitterbox edition in London. “I was like, ‘What’s Glitterbox?’ Obviously I knew Simon, knew Defected and said, ‘It’s gotta be something special if they’re involved’.” Up until this moment Glitterbox was a strictly Ibiza affair, but he said yes to a set at the Loft room in Ministry. His task was simple. “Simon said to me, ‘Just don’t sound like the rest of the club’.” So he dug deep into his funk and soul collection, dropped a few house cuts and steered clear of the disco anthems.

Soon enough he came up with the idea of a Glitterbox radio show, suggested it to Dunmore, and launched it in 2017. It was — and remains — a hit, syndicated across more than 40 radio stations, heard in 25 countries, and with over 12 million listeners a month. For the past six years Baptiste has been the voice of Glitterbox, interviewing Jazzie B, George Benson, Jazzy Jeff, Eddie Levert of The O’Jays, Kathy Sledge of Sister Sledge, Armand Van Helden, Gilles Peterson and even Elton John. “Every single week — recording these interviews, putting the shows out, waiting for reactions. It was a crazy time.”

Glitterbox radio took off in ways he hadn’t imagined, attracting a dedicated following, which in turn put some pressure on his Mi-Soul gig. Something had to give. “I could have done both — nobody said ‘You need to stop this’, but I was so overwhelmed with what was happening at Defected, I didn’t have the capacity to keep going into Deptford every Saturday morning and do this radio show. It took a lot of work.” We ask our favourite record question: which bits of vinyl would he save in the event of a fire? “Oh Jeez,” he replies, making a beeline to a particular shelf in his collection. “I know the first one, it’s ‘God Bless’, Otis Redding's brother Dexter Redding put the record out. My dad used to play it when I was young, and it means a lot.”

We follow him over to his collection on the other side of the room, which is where we spend most of the interview, ground-level, settled in the soft give of his carpet. We spot a Teddy Pendergrass record and get chatting about the Blue Notes soul singer. “They were ear-marking him, they were calling him the Black Elvis — that’s the level of stardom he was on the road to,” Baptiste explains. “He’s just raw energy for me. To hear that voice come front the pit of the stomach — when he got into his solo career they realised what sex appeal he had, so they started putting out songs that were basically just for women. If you look at some of the songs you can see what they were trying to do.” He flips to the back of a Teddy record and lists a few track titles: ‘Close The Door’, ‘Turn Off The Lights’, ‘Feel The Fire’. Point taken. “I just think those characters come along every so often. They’ve just got that thing, they’re just electric.”

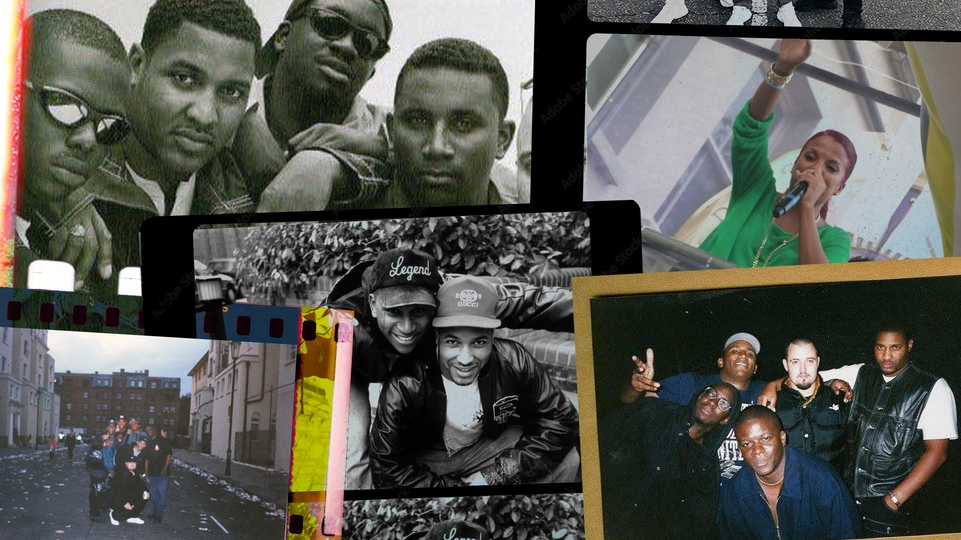

Another question — are there any records people might be surprised to hear he has? “Yes,” he replies, his back to us, rummaging through that initial shelf. “Bottom right is purely garage and early grime.” Having come of age when garage hit the mainstream, the young Baptiste bought every record he could get his hands on. But, he goes on to explain, the stripped-back beats and bass that followed courtesy of grime didn’t appeal. “All of a sudden it got dark. A lot of the fun elements went away. It turned into loads of dudes. It changed a lot.”

Baptiste keeps rooting through his collection, pulling out records, sharing a quick anecdote before moving on to another. He drops Sampha’s ‘Process’, Fonda Rae’s ‘Living In Ecstasy’ and ‘Just Can’t Give You Up’, a track by US soul group Mystic Merlin. We spot some hip-house in the mix too, as well as the soundtrack to 1984 film Breakin’. “Favourite film as a kid growing up,” he tells us, plopping the record in front of our feet. “I watched it relentlessly. It’s different crews breakdancing, battling against each other. Turbo and Ozone just had some magical scenes.” He pulls out a Tom Misch record, ‘Beat Tape 2’, taking him back to the mid-'10s, the popping days of SoundCloud, before dropping names like Jordan Rakei and Loyle Carner into the mix. “These were artists I was really pushing hard on the radio show — now he’s a superstar. I knew Tom was gonna smash it.”

Having firmed up his soul, funk and disco credentials on Glitterbox radio, Baptiste is returning to contemporary soul, a scene growing new sonic roots. The Remedy Project, launched under Defected in 2021, serves as an outpost for artists bringing through soulful elements. “Remedy is my baby,” he shares. “It’s an extension of the radio show I did on Mi-Soul for seven years.” While not genre-specific, Remedy places an emphasis on conscious lyricism and live instrumentation. Where Glitterbox pays homage to dancefloors past, Remedy takes things forward. “I guess I want to put out records that make people say ‘What the fuck is that?’, stuff that perks my ears up,” he says. “There’s no rules — if I’m into it, then I’ll try and make it happen.”

So far, Remedy has released the works of Hadiya George, Jitwam, Donae’o, Terri Walker and T.Williams. The latest release, ‘City’, pairs UK soul legend Omar with GRAMMY and BRIT Award-winning singer Joss Stone — Baptiste is on remix duties. He’s also stepped up with his own release this month, ‘Sweat’, on Glitterbox Recordings. “I never wanted to start the label and be confined to one genre of music. I just wanted it to feel like contemporary soulful music. We’re two years in and we’ve been able to tell that story pretty well.”

He’s been most proud to platform artists that he believes can take this UK sound to the next level, like singer-songwriter/producer Shiv. “Everytime I watch her I’m just like, ‘You’re a superstar’. She’s got such a lovely energy about her, and she’s such an amazing songwriter. If she doesn’t blow I will be gobsmacked.” He also gives a shout out to Kay Young, a British rapper and musician starting to catch the spotlight. But what Baptiste really wants is for the label to nurture the UK’s next big talent, a collective that can be the face of a burgeoning movement. “Do you know what I want? It’s good to put things in the universe: I want a group, the 16-year-old versions of the Ezra Collective. I want horns, bass men, and I want to give them all the love, help them make records, give them studio time, just a band that we can help and smash.”

We head south to Notting Hill, a 45-minute journey from Watford, arriving around the same time as Baptiste. He jumps out of his car and heads to the former Good Times bus location, a spot now occupied by an apartment building. Almost immediately he clocks the black gates opposite the flats and heads over. These railings, which mark the perimeter of a 1930s block, are where punters used to turn their back on the crowd and quietly relieve themselves, Baptiste explains. “We’d hang our bag of beers on the railings and turn around,” he says, motioning as if to recreate the scene.

By his mid-teens, August bank holiday weekend had become its own ritual, staying over at his uncle’s and heading into Notting Hill Carnival together, sometimes by car, other times on chopper bikes. He started out as a box boy, setting up and taking down the sound system, as well as selling Budweisers from a stall — was he of age? “Course not,” he replies. Good Times, however, lost its carnival spot in 2014 to regeneration. “They offered him another spot in a shitty little corner, but it just didn’t make any sense.” A smaller sound can be found there every last weekend of August, but as far as Baptiste is concerned, it doesn’t compare. “I can’t even look at it — weak sound system,” he winces at the memory. “Norman was Carnival for so many people, so when Good Times was no longer there it was such a blow.”

He’s not sure how old he was when he played his first set on the sound, so we throw out a few numbers. “Nah, he wouldn’t let me at the decks when I was 16, no chance — I can remember playing Jamiroquai’s ‘Space Cowboy’ though. It’s the one song that I’ve got a video of,” he smirks. Lenny Fontana’s ‘Spread Love’ may have also made it into that 45-minute set, but the main memory that stands is Baptiste being too nervous to look up and into the crowd. “I wasn’t even playing for them, I was playing for Norman, thinking, I hope he’s happy.”