Don't Ever Stop: Tony De Vit, Trade, and the infinite energy of hard house

Flawless DJ, frequent hitmaker, dedicated mentor: Tony De Vit was a true hero of UK dance music. The most high-profile resident at hedonistic queer club Trade, he helped create the hard house sound, and was renowned not only for his impeccable mixing, but his compassion and care for others. Ahead of a new documentary, and with hard house at large once more, Stewart Who? reflects on his legacy with those he was close to, and those he influenced

In case you hadn’t noticed, hard house is back. Though for some, like the ill behaviour, it never went away. A new generation of DJs and club kids are inhaling those galloping BPMs with heady enthusiasm. This summer, hard house went large, finding a fresh fanbase at dance events and festivals. However, the story of this phenomenon started over 30 years ago. The eruption of hard house is deeply linked to a club called Trade and the late, great DJ and producer, Tony De Vit. By any standard, the epic story of this genre and its most heralded champion feels like a queer fairytale mixed with a Greek myth.

Trade launched at Farringdon’s Turnmills in 1990, becoming London’s first legal after-hours club. It was the creative spawn of Laurence Malice, a whirling dervish of the capital’s avant-garde art scene. The Malice philosophy? “Good clubbing is based on exhibitionism and voyeurism. You can’t have one without the other.”

The doors to Trade opened at 3am on Sunday mornings and the party would kick off with deep and chunky soulful house from DJs such as Martin Confusion, Alan Thompson and Smokin’ Jo. Steve Thomas turned out tough, driving house. DJ Malcolm Duffy pioneered experimental tribal. Daz Saund and Trevor Rockcliffe served a sunrise riot of extreme techno. As the clock lurched past dawn, the beats became faster and Tony De Vit was the man who drove that dancefloor to the fast lane.

The club became notorious for a merry form of aural warfare. In a dance of unholy alliance with the DJs, Trade devotees were gluttons for extremity, cheering for ever weirder and harder sounds. The residents enjoyed testing the limits of sonics and sanity. Was it possible to hear drills and satanic howls over machine-gun drums while porn movies flickered on TV screens? Probably. Would you see glammed up trans girls in glitter bikinis dancing on the bar? All the time. Could a punter body-pop into amyl-fuelled orgies on the dancefloor? Quite likely. That was the appeal. It wasn’t for the timid. You either lapped up the lunacy, or fled. Trade made no apologies. The message was clear, ‘Our hardcore is harder than yours’.

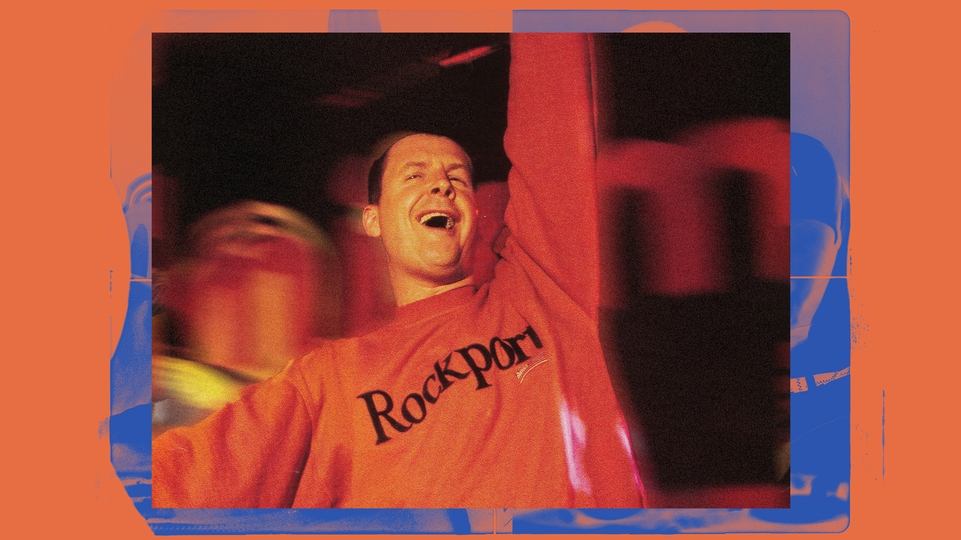

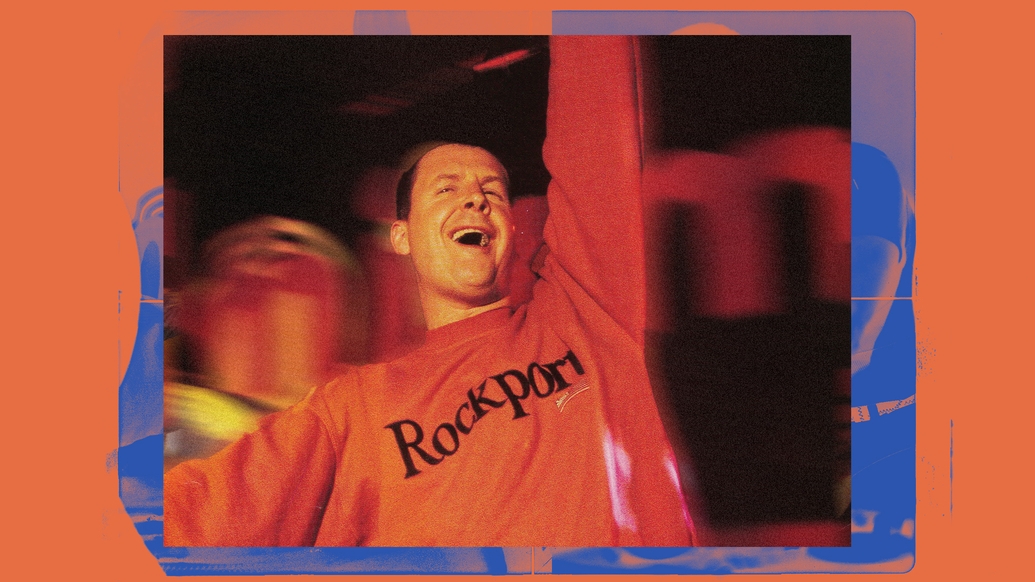

In the underground cauldron that was Trade at Turnmills on a Sunday morning, something magical happened when De Vit hit the decks. Molecules shifted. The air became agitated. The crowd would be wet with sweat, but then Tony’s turntable throwdown would launch an even deeper heat of fiery intensity. His mixing was so masterful that it felt like walls of sound were pummelling the senses. It was never less than an overwhelming experience.

The joy Tony De Vit brought to Trade would surge through the club with rippling power. Pupils swelled to shiny, black saucers. Wobbling grins blessed a sea of faces. Some people just gawped in awe. Trade was probably frightening for first timers, but it was life-changing for thousands. In the history of clubs, New York has Studio 54. Berlin has Berghain. Manchester has the Hacienda. London has Trade as the decadent gem in its raving crown, and Tony De Vit as the master of its dancefloor.

The club pulled in a rum bunch of misfits, party freaks and disco addicts. Trade wasn’t just gay, it was radically queer with a defiant smiley face. Attitude was everything and out on the streets, the fight was real. In the early ’90s, AIDS and homophobia were a fatal and scary brew for the LGBTQ+ community. Death loomed large, and Thatcher’s Section 28 demonised an already beleaguered section of society. The Tory law prohibiting local authorities from the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ stayed in place until 2003. It gave a sly green light to prejudice and damaged a generation. The current political climate seems to echo this ugly past, especially with the aggressive rhetoric towards trans people.

‘Gay bashings’ were not uncommon in the '80s and '90s. With the Met’s reputation for homophobia, most victims of homophobic crime swerved the law and persevered in silence. Trade was a weekly ‘fuck-you’ to the ever-challenging landscape. It quickly became THE place to let off steam and rave the pain away. It was a grim time to be gay, but this hedonistic club in Farringdon supplied nuclear levels of therapeutic fun.

S&M lesbians, go-go boys and drag queens rubbed up against downlow lawyers, pop stars and supermodels. It was a revolutionary cocktail. If Hieronymus Bosch, the devil and Dionysus had designed a disco, this was it. When MTV tried to film in the club, their cameras malfunctioned due to the euphoric mania and dripping humidity. The director sighed in disbelief: “We didn’t even have this problem in the rainforest”.

By the mid ’90s, this loopy speakeasy had become widely notorious. Massive queues ballooned outside Turnmills, causing daylight mayhem. Twitching hopefuls snaked round the block, turning sleepy Farringdon into a wide-eyed apocalypse. As the crowds flocked and begged to get in, Tony’s fame exploded.

Tony De Vit’s rise in recognition wasn’t a quirk of luck. Decades of hard graft and exceptional talent were the keys to his later commercial success. Tony had been DJing since the late ’70s, gigging at local weddings and regional hotels. In the ’80s, he held DJ spots at a host of gay nights in the Midlands, most famously Birmingham’s Nightingale.

He proved a hit on local radio, and in ’88, he bagged a residency at Heaven. At the time, the Charing Cross super-club was the most famous gay disco in the world and the loved-up hub of the exploding acid house scene (Shoom, Troll, Spectrum, Pyramid, Land Of Oz). Mark Wardel, who later became the manager of Trade and designer of the club’s iconic artwork, first encountered Tony in 1990 at a gay club called Recessions in the Brunswick Centre. “He was spinning hi-NRG and Italo house,” Wardel says. “I have a cassette of one of the Recessions sessions, which I still treasure to this day.”

It was a bag of carefully crafted C90 cassettes that landed Tony a job at Trade in the club’s early days. He was already in his 30s, when in ’92, he teamed up with Simon Parkes to launch the V2 Recording Studio. Today, the building in Birmingham that housed their project, The Custard Factory, hosts a blue plaque memorial, celebrating Tony’s life and work. He’s the first DJ in history to receive this honour, and the tribute secured his reputation as ‘The Godfather of Hard House’. Between ’94 and ’98, Tony produced and remixed over 100 tunes at The Custard Factory, including 11 UK chart hits under his own name.

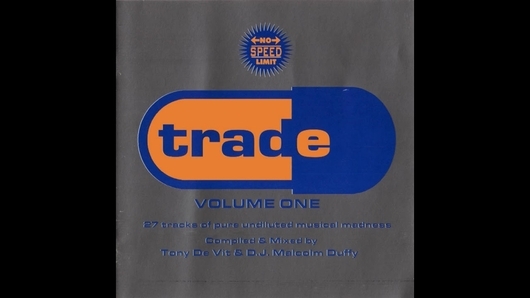

In the mid-’90s, Trade’s pill-shaped flyers made a justified claim to be ‘keeping the vibe alive in ’95’. It was a pivotal year for Tony, and the club that crowned him. Trade released their first album that year, compiled and mixed by Tony De Vit and Malcolm Duffy. The double drop of ‘musical madness’ was pitched as having ‘no speed limit’. Tony also released ‘Burning Up’ in 1995. This uplifting tune turned into a boiling hit, and Tony’s high-speed ride accelerated into an excess express.

‘Burning Up’ bounced into the Top 40 at No. 24, and in a flash, Tony became a pop-up dance act. In a promo for the single, he frolics in a full-length fur, playing a Svengali maestro while twirling a Dali-style 'tache. It’s tongue-in-cheek, self-aware, and oddly prescient. The ‘Burning Up’ video will never win the Turner Prize, but it’s plain to see Tony’s having the time of his life. Prior to release, he’d been spinning ‘Burning Up’ at Trade for months. It always caused merry chaos. The Trade fanatics were loyally proud of Tony, and would grin and gurn with misty eyes on hearing his crossover hit. When the hoovers kicked in and the crowd roared, Tony would beam back at the dancefloor, revelling in the blissful mess of it all.

In ’95, Tony recorded his first Essential Mix for BBC Radio 1. That debut appearance went on to win Essential Mix of the Year, voted for by the listeners. He featured on 12 of the best-selling dance compilations in 1995, and his mix of ‘Hooked’ by 99th Floor Elevators went from underground white label to absolute anthem. That summer, he also played a 12-hour set at Trade. It seems like an insane venture, but he nailed the marathon, spanning many genres of house and proving beyond doubt that his skills were at best Olympic and possibly superhuman. He’d hit the big time, but Tony was about to enlarge the life of an unknown teen in Larne, Northern Ireland.

Robert Ferguson dropped out of school at 13. While focused on footie for a few years, the adolescent’s kicks came from dreams of being a DJ. At night, he washed glasses and wiped tables in a local nightclub. By day, he spent his cash on vinyl. He was also selling LSD and amphetamines. The teen was quite a handful for his family and the local neighbourhood.

Too tiny to reach the decks, ‘Wee Fergie’ used upturned milk crates to practice mixing. In ’95, when Tony De Vit landed in Larne to play the Kilwaughter House hotel, Ferguson fought his way to the DJ booth and badgered the bemused DJ. It paid off. He met his idol and left with Tony’s phone number. This was the dawn of an infinite union and a fabled raving apprenticeship.

The teenager called three or four times a day, and thanks to this persistence, became part of Tony’s life, but it was a steep learning curve. Ferguson had never met anyone who was gay and had no idea about Tony’s sexuality. On the night they met, after helping Tony lug the vinyl back to his hotel room, Fergie was surprised to find the local lads calling him, ‘Fergie the f****t magnet’. Tony didn’t come out to Fergie for almost another year.

“He called to say that I couldn’t visit him in England,” Fergie says. “Firstly, because of the age difference, then he said, ‘And I’m a poof’ and put the phone down. Then he rang my mum and said that 'cause he was gay, it wouldn’t look right.”

Fergie’s mum was wisely pragmatic. Her son had found a calling, and a mentor she loved and trusted. On a Zoom call from Las Vegas, where he now lives, Fergie laughs, “Even if they said I couldn’t go, I’d have gone anyway”.

Despite the raised eyebrows, following their initial meeting, Tony grew close to the Ferguson family, staying at their home in Larne whenever he gigged in Northern Ireland. In 1996, Fergie moved to the UK and into a house share with Tony and his boyfriend, Andi Buckley.

“When he came over, it was like he was part of the family,” admits Andi. “A bit like a little brother for me to look after. Tony took him under his wing as mentor. And I took him under me wing too, because we were both troubled, I think, at the time. Fergie in Ireland, me in Birmingham. We were both taken away from what I guess could’ve evolved into a much worse life.

“Obviously, after Tony passed, I then took up the role of looking after Fergie and managing him. So, I went on to continue what Tony set off. And you know what? We’re still like brothers today.”

"That’s Tony’s legacy. It’s the music, and helping people achieve their dreams. He gave words of advice to many people, and since then, they’ve told me that Tony inspired them. His words stayed with them forever." – Andi Buckley

Robert ‘Fergie’ Ferguson, the lad from Larne, soon found himself at six gigs a week, with Tony giving his prodigy slots at big parties such as Gatecrasher, Godskitchen and Cream. Tony De Vit proved a tough tutor. If Fergie’s mixing was anything less than flawless, Tony would sling the offending mixtape from the car window as they drove between gigs. In ’97, with a blessing from Laurence Malice, Fergie played at the Trade ‘Test Lounge’.

“My first record kept skipping,” sighs Fergie. “But a big drag queen danced over and just stuck a lump of chewing gum on the cartridge. The tune stopped jumping and it just went off from there. You couldn’t make it up.”

His inaugural set was a sensation and overnight, Fergie became a member of the Trade crew. He was still only 16. As Fergie braved the chaos at Trade, Tony’s star continued to rise. His mix of Louise's ‘Naked’ earned Music Week's vote as most 'Groundbreaking Remix of ’96'. The following year, Tony bagged his own radio show on Kiss FM and was ranked No.5 in DJ Mag’s Top 100 DJs. By the next year, he'd be gone.

In July 1998, aged only 40, Tony De Vit died due to complications related to living with HIV/AIDS. He’d only been diagnosed nine months earlier. Tony kept his status private, except to those very close to him. While some medication was available, HIV treatment was still pretty experimental. The reality of the period was that medical trials proved too late for some, and gruelling for many. Death rates continued to rise. Tony didn’t respond well to treatment and sadly, the world lost one of its finest DJs. Asked how he felt when Tony shared his diagnosis, Andi Buckley says: “It was upsetting, but if you love someone, you’re there for them. I wasn’t going anywhere.”

The landscape is very different today. Those who are HIV+ can take one tablet a day and live a long life, free of complications. In 2023, people on HIV medication are unable to pass the virus on.

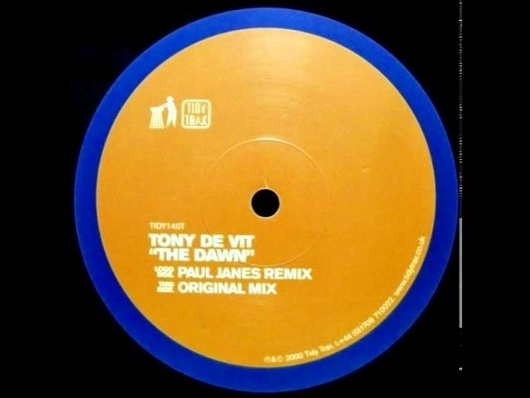

By the time Tony told his loved ones he was unwell, symptoms were already proving a challenge. He was struggling with fatigue and losing sensation in his feet. Due to nerve issues, burning pains were affecting his mobility. As they hurtled up and down the UK’s motorways, clocking several gigs a night, Fergie would be in the back of the car, massaging Tony’s legs. Despite wavering health, Tony’s schedule was a whirl of global travel and high-profile production work. In early ’98, he recorded ‘The Dawn’ with Paul Janes and Andi Buckley. It’s considered by many to be his masterpiece.

After suffering bronchial issues on holiday in Miami, Tony flew back to the UK and spent the last six weeks of his life in a hospital in Birmingham. It was gruelling and heartbreaking for all concerned. Aware his life was ending, Tony’s last words to Fergie were, “I’m not gonna get to see who you become”.

Tony’s life stopped at the peak of his career. There’s no doubt he was destined for even greater success. One of the first Global Underground mixes, ‘GU05: Tony De Vit — Tokyo’, was a fitting tribute to the man and his music. The 25th anniversary of his death this year prompted a crop of projects that celebrate his work. Tidy Trax released a compilation of his productions, remixed by Patrick Topping, Nicole Moudaber, Eats Everything and Hannah Laing. The BBC paid homage to Tony’s career by re-broadcasting his Radio 1 Essential Mix from ’95.

Perhaps the most intriguing celebration of Tony’s life is the release of a documentary exploring the impact he’s had on dance music culture and the lives of those around him. Don’t Ever Stop: Tony De Vit by Phill Smith and Stuart Pollitt of Restless Films looks set to be the dance doc of the year. Smith’s journey started on the dancefloor of Sundissential, where he heard a mix of ‘The Dawn’ by De Vit, and then DJ sets by Fergie. He became hooked on hard house, but also drawn to the colourful tapestry that weaved together a teen from Northern Ireland and the man who made him a player.

“I thought Tony's story had everything,” explains Smith. “Love, sex, massive highs, sudden tragedy and a real legacy. Throw in a generation of clubbers who’ve lived through an epidemic, some happily raving shoulder to shoulder with anyone who loved the music, and some desperately needing the rave as their only escape. It felt like a great story.”

The documentary isn’t just aimed at wistful clubbers. It’s a rollercoaster ride through the ’90s, dipping into the hedonistic madness of it all. No social media, very few cameras and a subculture thriving on chemical abandon and unpretentious fun. It features Judge Jules, Danny Rampling, Fergie, Andi Buckley and Tony’s sister, Jayne De Vit. Don’t Ever Stop: Tony De Vit doesn’t flinch from the tough stuff, as the club scene led to many casualties along the way. An interview with the legendary Madders from Sundissential highlights how addiction can grip, then spin out of control. Fergie admits to being in treatment for alcohol issues, having struggled with booze for years. It’s a lovely celebration of that period and this crazy rave family at the centre of it all. It’s also a thumping love letter to Tony De Vit.

“We’ve tried to make something that appeals to both hardcore fans and the general viewer,” admits Smith. “It’s not a critical breakdown of the genre of music Tony championed. There’s a universal human story at the heart of the film, involving Tony taking a chance and helping Fergie and Andi. Then the two of them helping care for him after he became ill and vowing to carry on his legacy.”

“He hated that magazine headline ‘The Queen of Hearts’, but he DID have a big heart and always had time for others,” Andi Buckley says. “That’s his legacy. That’s what we’ve done with the TDV Academy. It’s to give kids an opportunity to just DJ, with no cost to themselves. Because we can. And we want to. That’s Tony’s legacy. It’s the music, and helping people achieve their dreams. He gave words of advice to many people, and since then, they’ve told me that Tony inspired them. His words stayed with them forever. He was powerful like that. A powerful human. I owe him a lot. And I was lucky enough to be with him till the end.”

After Tony’s death, Fergie took over his slot at Trade and then went on to become a global star. He was voted into the top ten of DJ Mag's Top 100 DJs list, was a Radio 1 presenter for many years, and in addition to setting up his own label, became an award-winning producer and remixer. Like the David Beckham of DJs, he graced the covers of magazines, moved to the US and is now resident at Wet Republic pool party and Hakkasan in Las Vegas, and HQ2 Nightclub in Atlantic City.

Tony De Vit’s death spelled an untimely end of his life, but the man lives on in many beautiful ways, not least in Fergie’s life and work. He remains in the memories of the thousands of fans who were lucky enough to hear him play or be inspired by his advice. The Tony spirit is alive in the community work with kids at the TDV Academy.

His legacy? Making many generations of people intensely happy, all over the world. Breaking down barriers. Creating shared joy on a dancefloor. Uniting a crowd in a moment of wonder. That’s a rare gift to humanity. Most importantly, Tony De Vit will be everlasting, thanks to his music. Diamonds keep on shining, and bangers are forever.

Don’t Ever Stop: Tony De Vit by Restless Films is featured in the Doc’n Roll Festival throughout November.

'TDV25 – Tony De Vit – Greatest Hits’ is out now on Tidy Trax