30 years of Trade: celebrating the boundary-breaking LGBTQ+ rave

The fierce LGBTQ+ party Trade was the UK’s first legal after-hours club event, opening at 3am and closing at 9am. It laid the groundwork for a new on-and-on party culture, while its sexual and gender diversity was a forerunner for today’s queer club scene. As it celebrates its 30th anniversary, and prepares for its 24-hour birthday party at Egg London, Joe Roberts speaks to some of its regular DJs, designers and founder Laurence Malice about Trade's boundary-breaking legacy

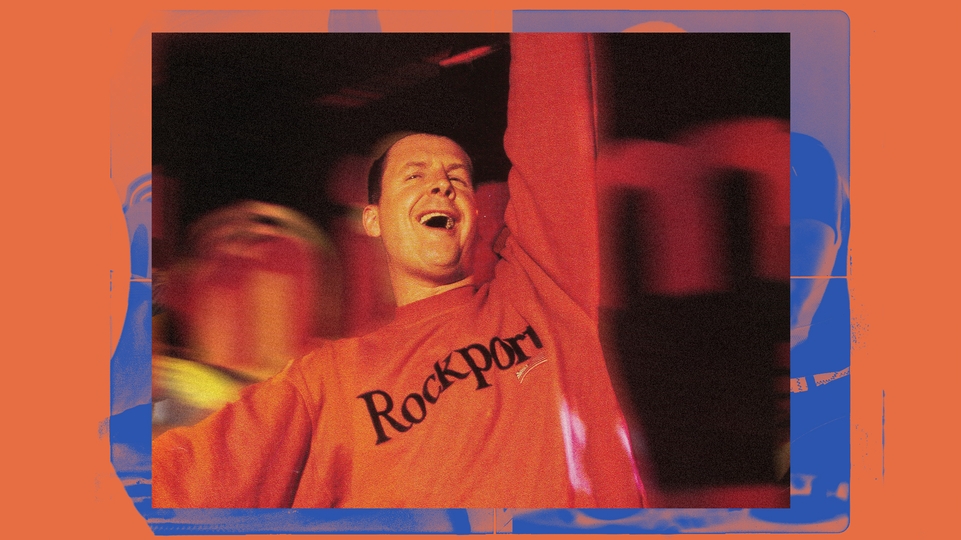

It’s Sunday afternoon, 16th March 2008, and the dancefloor of Turnmills is packed with dancers in varying states of undress. Watching over them, grinning maniacally, is a painting of a giant, muscular orange baby — just one of a number of brightly coloured banners hanging from ceiling to floor. Shrouded in darkness, DJ Pete Wardman plays his final track, Marmion’s remix of their own trance classic ‘Schöneberg’. As the synth breakdown hits, a collective cheer of euphoria rises, smiling faces looking around at one another. The music suddenly stops, leaving the emotional outpour hanging. Then it kicks back in, the dancefloor reduced to a blur of motion.

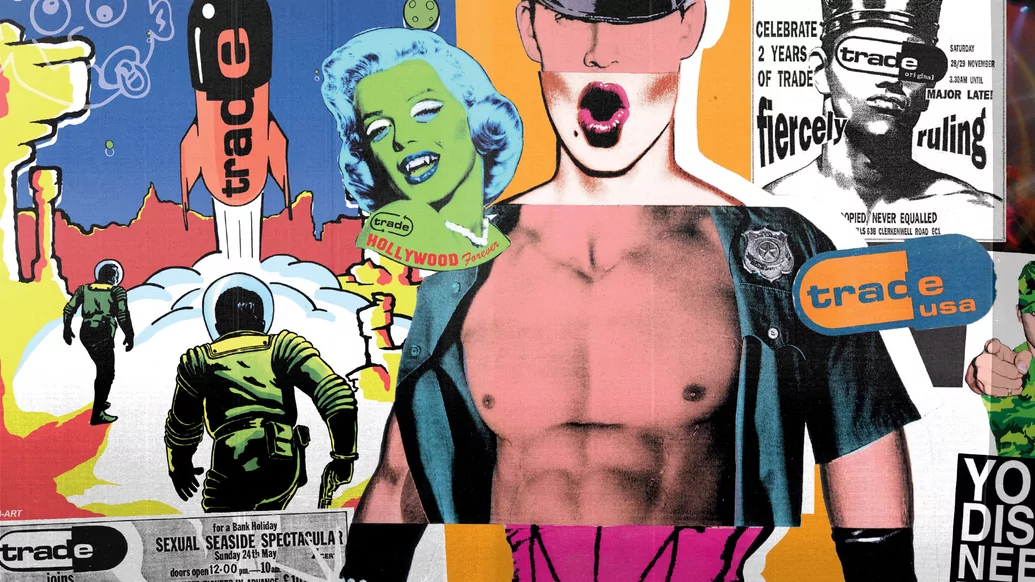

So ended Trade’s weekly 18-year run at Turnmills, a historic moment preserved in low definition glory on YouTube. It was a reign that redefined the face of global clubbing. The UK’s first legal after-hours, opening at 3am and closing at 9am (an end time that got later and later as the years went by), it laid the ground for a new on-and-on party culture, while its sexual and gender diversity was a forerunner of today’s queer scene. The ‘Trade Sound’, born among the DJs who played there, championed new movements, eventually evolving its own distinctive hard house sound for the peak of the morning. And its bold, tongue-in-cheek artwork and flyers, the work of in-house artists TradeMark, Martin B-Art Brown and Mel Devine, gave it an iconic, arresting visual identity.

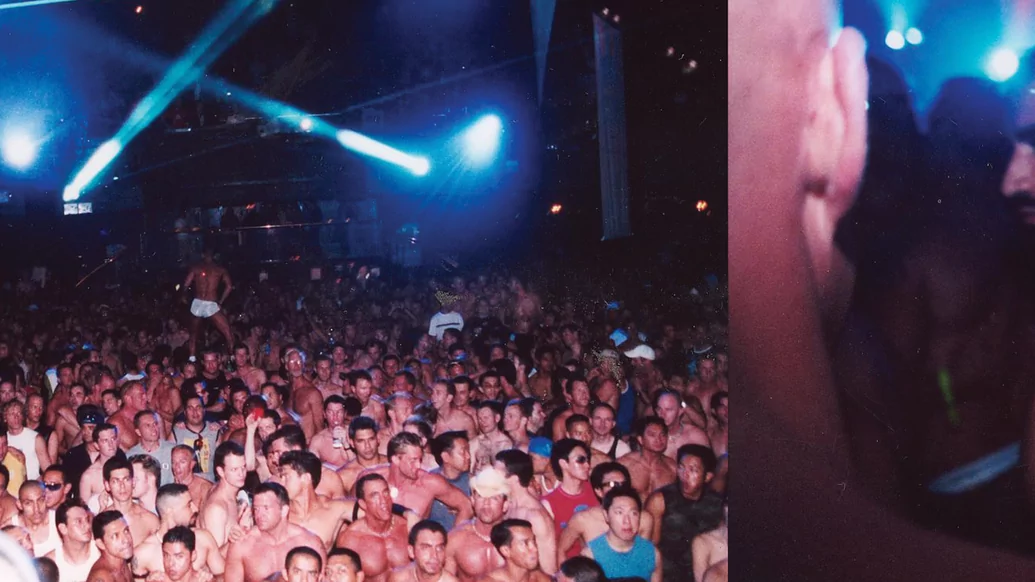

With demand eventually spreading abroad, Trade spawned spin-off parties in LA and New York, Amsterdam and Paris, while other foreign jaunts included Berlin’s Love Parade, two seasons at Ibiza’s infamous Manumission and a tour of South Africa. The latter was captured in 1998’s Channel Four documentary The All Night Bender (named after Trade’s original motto). Providing insight into the transformative power the club had on its regulars, affectionately known as Trade Babies, it also took a close-up look the camaraderies of some of the DJs who soundtracked this magic — Pete Wardman, Ian M, Malcolm Duffy, Alan Thompson, Steve Thomas and Tony De Vit, Trade’s most iconic star who sadly died in 1998 — and introduced promoter Laurence Malice, Trade’s guiding force.

Confessing to camera, “My biggest insecurity is not owning my own venue,” by the time the documentary had gone out, Laurence had bought a King’s Cross warehouse. Originally offices for Trade, in 2003 it opened as Egg LDN, his own multi-room nightclub. This hosted Trade’s 25th birthday in 2015, billed as the final ever party — commemorated with an exhibition, Often Copied, Never Equalled. But as we enter 2022, Trade returns to the club on 12th and 13th February for a belated 30th birthday celebration, setting the scene for a new beginning.

Origins

“I’ve lived a life,” confesses Laurence, when we sit down in a hotel bar to dig into Trade’s origins. Born to Irish parents in Manor Park, East London, he began hitch-hiking to clubs while still at school, much to the chagrin of his mother. Not much older, he followed his then-girlfriend (“I was always fluid,” he states) to Australia, starting punk band Larry Malice & The Razor Sharps and hanging out with Nick Cave’s brother. Overstaying his visa, he was forced to leave, but brought home a taste for putting on parties.

Back in London in the early ’80s, he and Renegade Soundwave ran an illegal after-hours club in a Camden sauna — an underage Tim Simenon, later of Bomb The Bass, playing hip-hop mixed with Klaus Kinski speeches to an audience that included Sue Tilly, Leigh Bowery, Michael Clark and Princess Julia. “It was funny to see Glen Matlock [of The Sex Pistols] sitting in a sauna in leathers,” he recalls, the party closing down after the sauna leaked onto the Tube line below. It was a close-up experience, however, of the creative energies that converged when everyone else had gone to bed.

Laurence’s restless sociability led him to Iain Williams, with whom he formed musical duo Big Bang. Sharing Abba’s publisher, they covered ‘Voulez Vous’ and came second in a 1989 International Songwriting Competition. More importantly though, their Farringdon-based manager introduced Laurence to Turnmills, castigating him, “you’re spending a fortune on your outfits, you need to go out and work. I’ve got a place down the road.”

“I hated it,” was Laurence’s first impression; the club was not the sprawling venue it evolved into over Trade’s lifetime. “It had carpet all over, a circumference of about four feet, and a metal dancefloor. As soon as anyone dropped any drink on it, they’d fall all over the place.” Yet with a characteristic persistence, he tried his hand at various parties.

"[Trade] attracted people from across the board. You could do a 360 and see Muscle Marys, trans people, drag queens, the heaviest of gangsters, off-duty police and loads of straight people, all having a ball” — Martin B-ART Brown, Trade designer 1991-2000

Utopian Freedom

When it launched in November 1990, Trade’s after-hours presence struck a chord. “This was the era of the AIDS epidemic, people were scared of what was going on in the world,” Laurence says, explaining how he had read about gay-bashing in newspapers. “Clubs finished at 3am and these queens didn’t want to go home, so they went out cruising. I wanted to give them a safe environment.” Trade was also the first time he felt creatively free, programming a soundtrack that evolved throughout the night and decorating the venue to become a self-contained world.

“I just turned up with a carrier bag of fierce records and told Laurence I wanted to play,” says Malcolm Duffy, one of the original Trade residents, who joined Martin Confusion, Daz Saund, Trevor Rockliffe and Smokin Jo. “I knew I had something different to offer, as my US house tastes encapsulated tribal, house and garage, but with a certain Malcolm tough edge.”

Contrasted by Daz Saund, who Laurence calls “the first person playing Detroit techno in the UK”, from the outset Trade employed a collection of DJs who were serious about music and could provide a progressive musical journey.

This distinctive sonic identity was matched by Trade’s ever evolving visual aesthetic. Brought onboard six months after it opened, Tim Stabler, who’d previously been running Troll club, was pivotal in helping with promotion and production. “This really helped elevate Trade to a new level and he was an integral part of the Trade collective,” remembers Laurence. “I was really sorry to hear that he passed away last year. He was a real clubland innovator and a thoroughly nice guy.” When Tim left Trade, artists Martin Brown, Mel Divine and TradeMark took over creative direction, then later still Mark McKenzie, aka Edna, who worked with Laurence to bring his concepts into reality.

Originally working the door, TradeMark, aka Mark Wardel, was responsible for the club’s flyers, whose striking originality led to them becoming collector’s items. Intentionally steering away from the gay club trend of using images of drag and leather queens, he instead drew inspiration from trips to New York, where he’d absorbed the work of Basquiat, Haring, Richard Bernstein and Stephen Sprouse. “I mixed up elements from that scene with bits of Soviet propaganda imagery and punk fanzine-type graphics.”

It set the tone and reflected Trade’s anarchic sense of utopian freedom. The club’s first attendees were what Laurence affectionately calls “sweaty on-ones”, high on ecstasy and not ready to go home. But as the years progressed, it encompassed distinct tribes. “The people were and are still fabulous,” says Martin B-ART Brown, now DJ Mag’s Art Director. “Obviously there was The Peggy Spencer Formation Dance Troupe — you had to be there. But it attracted people from across the board. You could do a 360 and see Muscle Marys, trans people, drag queens, the heaviest of gangsters, off-duty police and loads of straight people, all having a ball.”

Some became stars in their own right, such as Stewart Who?, who as well as working on Trade’s door, as an artist liaison and as one of the club’s chief photographers provided the arch vocals to Wayne G’s after-after-hours anthem ‘Twisted’.

“Being female was a plus point,” adds Smokin Jo, who was working in a Junior Gaultier shop in Soho when her manager, who was best friends with Martin Confusion, asked if she wanted to fill in for him. “The crowd put me on a pedestal and really gave me the confidence to play whatever I liked. There’s nothing more incredible than having a gay crowd scream, whoop and have their hands in the air when you play a tune they like. I felt very lucky to be a part of it, it was the best time of my life.”

This is one of the club’s lasting legacies, says Mark: “Trade broke down a lot of barriers between gay and straight.”

Hard House

Another legacy was hard house, the figurehead of which was undoubtedly Tony De Vit, who back in 1998 Laurence called “the best DJ in the world”. Drawing on elements present in the club’s early soundtrack — the hoovers of Belgian hardcore, sped up vocals from US house, the rattling pace of techno — it disassembled, then reformed these into a particularly English sound that became the zenith of the night, especially when De Vit was closing. “Techno with a bit of fun, a bit of trance,” is how Laurence boils it down, praising Tony’s instinctive ability to take people through all Trade’s musical gears — twice performing 12-hour sets at the club.

“What set Trade apart, and was a winning formula, was we only had resident DJs who worked closely together,” adds Alan Thompson, one of the later regulars. “We complemented one another to create what was known as ‘The Trade Sound’, which ran from the early sets of American tough house right through to full-on hands-in- the-air hard house and anthems.”

“Trade was such a huge inspiration for me to make music,” says another resident, Tall Paul, aka Paul Newman, whose dad John Newman owned Turnmills. Citing ‘Love Rush’, a breakbeat house stormer filled with uplifting piano and rave bass, produced under the name Decktition, as a track specifically written for Trade, he notes proudly it’s being played again by younger DJs such as Eats Everything and Ewan McVicar. Trade’s effect on producers stretched way beyond the floor of the club itself though, something Laurence eventually tired of.“After Tony’s death you had all these labels pushing out music for what was perceived to be a movement, but there was no quality control,” he says.

Despite its runaway popularity – hard house was going on to define the soundtrack of straight clubs across the north of England – not everyone was enamoured with it. “In 1997 we met up with Laurence and devised the idea of Trade Lite to look at the lighter side of house and disco, including elements of UK garage, which was exploding at the time,” recall The Sharp Boys, aka George Mitchell and Steven Doherty. Launching upstairs in a coat check room, while Turnmills was in the process of building a bespoke second room, this alternative sound went on to have a similarly wide-reaching effect.

“The other gay clubs in the UK took that essence of lighter music and ran with it for years,” says Laurence, name-checking clubs such as Beyond and Fire, and pointing to the renaissance of one of Trade Lite’s original DJs and stars, Fat Tony.

Celebrities literally queued to join the party, Guns N’ Roses’ Axl Rose famously turned away for past homophobic comments he’d made, and Trade travelled the world. Taking over the backroom of Ibiza’s Manumission at the height of its success in the late ’90s, Trade was responsible “for bringing techno to Ibiza”, according to Claire Manumission, who ran it with partner Mike. “All the music heads said the best music was there.”

But it was also a meeting of like-minds who recognised the people on the dancefloor and the ethos of the party meant as much as the music. “It’s all about a feeling,” says Mike. Or as Claire puts it, it was the excitement of never knowing what was going to happen, a shaking up of worlds that would never mix by day.

Life-changing

In the same period, Laurence was invited to New York to run Twilo’s Saturday nights. Malcolm fondly recalls playing alongside Danny Tenaglia there in 1996. But the club’s provocative marketing — putting an ad on the back page of a gay magazine, turned upside down so it looked like the cover, featuring a Russian boy, a cockerel and the caption ‘The Only Place To Get Your Cock Out This Easter’ — didn’t translate well.

“I found out who the true owners were,” says Laurence, intimating that what happened was enough to send him home — although Trade still provided the backdrop to a 2002 episode of Sex And The City. “New York felt very social,” says Martin, “but it was all about being seen, rather than bouncing round the dancefloor with no attitude or inhibitions. Trade was all about release and fun.”

This was fuelled, of course, by hedonism. Turnmills had the nickname Gurnmills and Jo recalls being found one night, after the record she was playing ran out, asleep under the decks from taking too many Es. “No one really cared,” she laughs. It was living for the night, yet Trade had a transcendent quality. Years later, the comments under the YouTube video of Trade’s closing moments echo, with still present emotion, the kind of life-changing sentiments you find under rave videos (A sample: ‘words will never describe. we were part of something revolutionary. chemical generation. still standing!’).

Laurence has his own moment frozen in time. “I’d be on the dancefloor listening to Vincent De Moor’s ‘Floatation’ and as it went through the key changes, I’d think, ‘I’ve had such a wonderful life, if I was taken now I’d be happy’. It was so emotional, the feeling we had towards this party.” Unlike the Catholicism of his parents, which promised salvation in the afterlife, Trade delivered it every Sunday by embracing earthly pleasures.

“It was all very spiritual,” Laurence agrees, when we draw a comparison. “The people beside me, the love, the hugs, the kisses, we were there together as a unity.” Such was its potency, doctors would advise patients who were unwell to find relief on Trade’s dancefloor. Some eventually had their ashes scattered there.

When Trade left Turnmills, the venue itself closing on 23rd March 2008, it felt like time. “To create it takes so much of me,” Laurence says candidly, explaining that he and others sacrificed so as to create an atmosphere that helped those who came flourish. He’d missed seeing his parents on the weekend, he says, as well as his nephews and nieces growing up. By the time Trade said goodbye, East London had also become a fully thriving entity, especially for gay nightlife — a legacy recognised by Islington’s Pride, who last year announced they were putting up a plaque to celebrate Trade at Turnmills and its contribution to LGBTQ+ history.

Fresh Horizons

As Britain slowly emerges from two years of lockdown, the need for release hangs in the air again. Parties such as Fold’s Unfold and Fabric’s Continuum are staking their own claims to extended-hours Sunday clubbing, evoking the spirit of Trade. Changes are afoot elsewhere too. Aided by Arts Council funding, Egg has planning permission to rebuild, promising bigger and better rooms, more outdoor space and better soundproofing, reflecting the ongoing transformation happening in its home of King’s Cross.

“Trade was always about cutting-edge music,” says Laurence, in response to those wanting to recreate what they had. Among the names on the 30th birthday line-up are original Trade figures such as Andy Farley, Smokin' Jo, The Sharp Boys, Tall Paul and Knuckleheadz, while Frankel & Harper and Remco Beekwilder are among the newer names getting their first taste of Trade. More names are still to be announced, and Laurence says the party will draw heavily on new talent, representing his first love, “the harder edge of techno”.

At the other end of the spectrum, he’s reprised the partnership with Iain Williams that first led him to Turnmills, the pair working on a Trade musical that Laurence promises will be like no other theatrical production. How could it?

“Trade was a melting pot of people, from all walks of life, gender and creed,” remembers Alan on the imprint left on those who experienced it. “It didn’t matter who or what you were as long as you had the right attitude, and this would be checked at the door.”

“It’s gone down in clubbing folklore, similar to New York’s Studio 54 and Paradise Garage,” adds Paul. “I’ve never been about looking back,” says Laurence though, once more steering Trade towards fresh horizons. “You’ve got to embrace the future.”