A history of UK sound system culture

Sound systems have driven the development of music in the UK, powered by hard work, passion and innovation. But preserving UK sound system culture, its knowledge and history, while also pushing it forward, is no easy task today. Ria Hylton traces its path through ska and reggae at blues dances in West Indian households, to soul, boogie, hip-hop and house in ’80s warehouses and at the Notting Hill Carnival, to nationwide tours and global popularity, and finds out how initiatives like the Sound System Futures Programme are seeking to secure its future

It’s the Thursday before Notting Hill Carnival and Linett Kamala, board director of Europe’s biggest street party, is weaving through the streets of Kilburn. Her Mini moves westwards, slowed by mid-evening traffic, and arrives on a quiet industrial estate in Wembley, just after 7pm. Kamala, who founded the Sound System Futures Programme, greets her teammates, Darren Watson and Terry Hooligan, and together the trio scale the narrow stairs to a brightly lit room on the top floor. Two students in the programme sit quietly among DJ equipment, awaiting instruction.

In 1985, Kamala was the first female to DJ at Notting Hill Carnival. The then-15-year-old opted for an experimental setlist in a reggae and dub-heavy soundscape, spinning go-go cuts like ‘The Word’ by Junkyard Band and Al-Naafyish’s ‘Time’, an early-hip hop track. Her funky, future-facing selections leaned heavy on the bass and stood her out among a sea of male-run sound systems. It was the start of a 30-odd-year journey that has Kamala back at the forefront of sound system culture — but this time, she’s manoeuvring others towards the stage.

“This programme is really about access,” the artist explains some days later. “Many people [involved in sound systems] have passed, particularly during the Covid period, and, like they say, a whole library has disappeared with them.” The passing of key figures — as well as the auctioning off of whole record collections following the death of a loved one, splitting up a lifetime’s worth of work — means technical and musical knowledge is being lost. It’s no small task, but Kamala and her team are eager to plug an institutional and generational gap, connecting Gen-Z enthusiasts with baby boomer sound system runners to pass on crucial knowledge about the culture, its history and traditions. “I wonder about the future of it, because it hasn’t really been thinking about the next generation. It’s in danger of dying out.”

Worldwide, sound system culture is booming, but not, Kamala notes, within the communities that birthed it. What was once a thriving scene linking West Indian households across the UK has now become a niche community practice celebrated by pockets of the culture. The Sound System Futures Programme hopes to reverse course, making sure descendants of the immigrant communities that shaped UK music are aware of and, in time, come to practise sound system traditions.

“On the one hand you want to hang on to certain things, because that’s what makes it special, and on the other hand, you want room for growth, innovation and experimentation, because that’s how things evolve.” Kamala pauses, mulling over her words. “And that was what birthed the sound system: someone figured out how to make things sound louder than they’d ever sounded before.”

“That was what birthed the sound system: someone figured out how to make things sound louder than they’d ever sounded before.” – Linett Kamala, Sound System Futures Programme

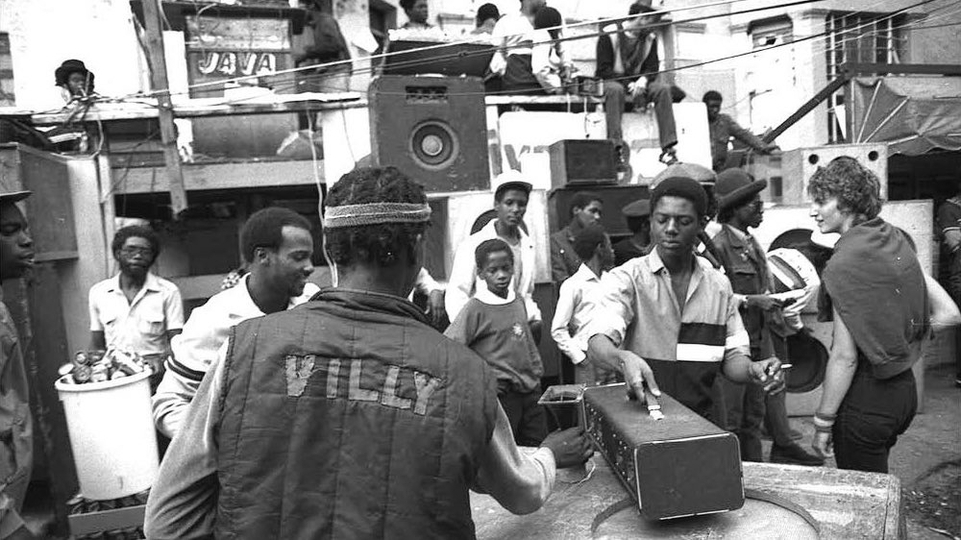

As the story goes, Duke Vin established the UK’s first Jamaican-style sound system. An apprentice of Tom Wong, who ran Tom The Great Sebastian in Jamaica, he learned the ropes from what was then the most revered sound on the island. Vin arrived in Britain in 1954, six years after the Windrush and four years before the first Notting Hill race riot, and a year later used his modest earnings to buy a 10-inch speaker and custom-made amplifier. He won his first clash against Count Suckle at Lambeth Town Hall in 1956 and was renting his sound out to blues dances: weekly parties held in West Indian homes. In exchange for a plate of food, drinks and music, locals would pay entry to these regular all-nighters, which helped cover rent and mortgage costs.

Sound system crews operated in highly structured constellations: box boys would do the heavy lifting, the manager organised bookings and collected fees. The technician was in charge of wiring and maintaining the system overall, while the operator would work the pre-amp — a bespoke mixer — maintaining the sound quality throughout the performance, adding the occasional sound effect. The selector would hand tracks to the DJ, and the DJ, who was not only responsible for playing tracks, would make sure the sound had the newest, most in-demand records. Finally, there was the MC, the mic man ‘nicing up the dance’ with toasts between transitions.

“The thing about blues dances is that it was always very dark,” Dennis Morris tells DJ Mag. “You had one light over the DJ and then in the middle of the room there would be a red light. The worst thing you could ever do is step on someone’s shoes; we’re very proud of our clothes.”

Morris, a photographer who grew up in the East End, documented the legendary Count Shelley and Admiral Ken sounds and saw these weekly parties as more than just entertainment: they offered a social environment hard to find outside the community. “There were very few clubs that we were allowed to go to,” Morris explains. “You didn’t feel comfortable so we created our own environment. It’s not like it is today where you can walk into a bar. It was ‘No Dogs, No Blacks, No Irish’.”

Blues dances, or shebeens as they’re commonly known, offered an inward, communal relief, a form of cultural continuity in an outwardly hostile space. “The most important thing about sound systems is they empowered us in our community,” Soul II Soul sound owner Jazzie B once said in a Red Bull Music Academy interview. “The sound system fed us, whether you were a carpenter or selling [food] as a vendor.”

These mini-economies lasted right through to the ’80s before dying out, but the crew structures remained and other traditions (dubplate, version, specials, etc). “I don’t know if it gets mentioned enough, but it’s the brotherhood, it becomes your extended family,” Zepherin Saint, who ran the Shock sound system, tells DJ Mag. “You argue, you hug, you love. It operates the same as any kind of family, because you spend so much time with each other, and musically you grow with each other.”

The first generation of West Indian migrants to attend blues dances were turned on to the latest rhythm and blues records from the US, as well as ska and rocksteady tracks. Trilby hats, tonic suits and brogue shoes were all the rage, and rum the drug of choice. But by the ’70s, reggae had taken pride of place in the dance and the clean cut look was replaced by something decidedly dishevelled. Second generation West Indians grew out and locked their curls, adorning themselves in the Rastafarian colours: red, gold and green.

Roots reggae, conscious-raising music, challenged narratives held by the elders, who, in their opinion, had worked too hard to assimilate, were too at peace with Empire. “A lot of our parents didn’t necessarily like reggae music, Bob Marley and the unkempt locs — anyone coming from a traditional Caribbean family will know exactly what I’m talking about,” Kamala shares with a light laugh, “but it was identity shaping. It wasn’t necessarily supported at home, so you were fighting on two fronts.”

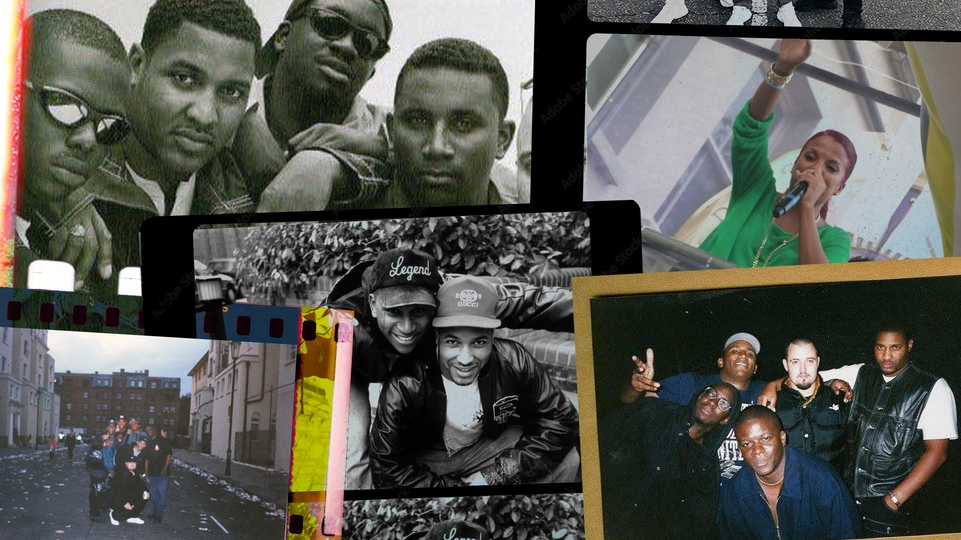

By the ’80s, sound systems were clashing up and down the country, with virtually every major city boasting a handful of crews.There were sounds in Manchester (Megatone), Nottingham (Top Notch), Derby (First Class), Reading (Resident), Coventry (Mackabee) and Birmingham (Quaker City), to name a few, and of course London had the highest concentration. Fatman Hifi was running out of Tottenham, Coxsone held a weekly residency in Dalston, Saxon was in Lewisham and King Tubby’s played in Brixton.

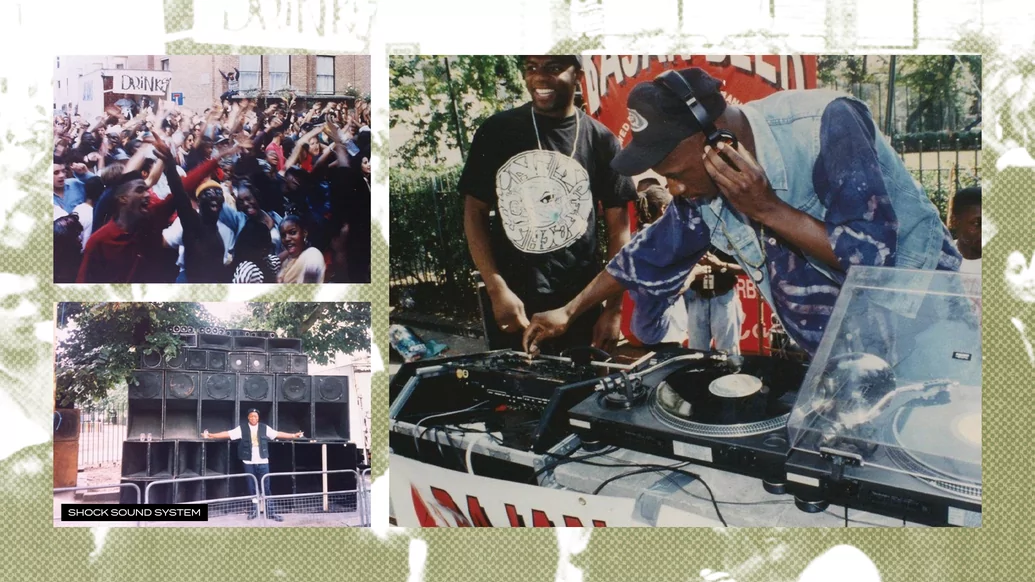

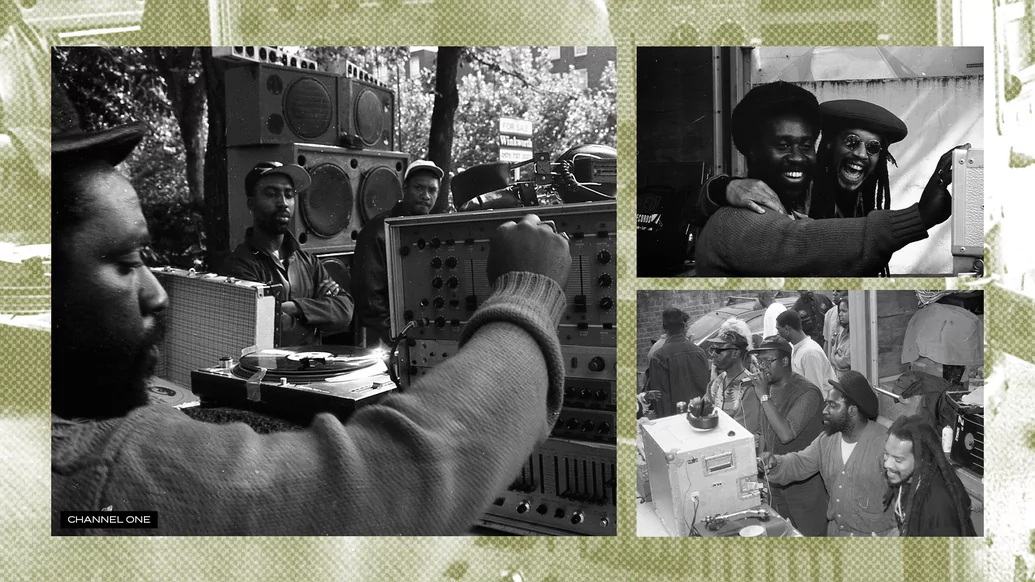

Channel One, a relative newcomer at the time, is preparing to celebrate its 40th year at Carnival when we catch up with co-founder Mikey Dread. After inheriting the sound from their father in 1979, Dread and his brother Jah T took the sound on university tours, introducing a whole generation of students to the culture. “The sound itself was an education at the time,” Dread tells DJ Mag. “When you’re driving House of Joy boxes, six or seven foot speakers into the university, that in itself was an education to them. We were shaking down buildings.” It was a time when ska was having a revival in the UK with the two-tone movement. Channel One played alongside all the big acts: Madness, The Selecter and Bad Manners, as well as UK reggae bands Black Slate and Aswad.

Tribe label head Zepherin Saint was among the leading soul sound systems in the mid-’80s, and witnessed the cultural shift from house parties to warehouse parties. “My first warehouse experience was Mastermind [sound system], and Tim Westwood was playing,” he tells DJ Mag. “It was New Years, ’84 in Cricklewood — that was amazing, and musically it was very electronic.”

These digitally-produced genres — electro soul, boogie and hip-hop, with artists like Luther, Harlequin Four, LL Cool J and Evelyn Champagne King — began to rule a small number of sounds, among them Jazzie B’s Soul II Soul, Norman Jay’s Good Times, as well as Saint’s Shock. “My brother was an electronic whizz, so he would build the actual amplifiers, as well as the speakers. A lot of them start in that way because it was too expensive to purchase.”

“Everything was turning into a discotheque, they basically pushed out the sound systems. That’s when the PAs started coming around. If it wasn’t for sound systems they wouldn’t have all these basses.” – Mikey Dread, Channel One Soundsystem

But the Shock crew fell in love with and began playing more house-focused sets; very soon, they were in no-man’s land. “The house party format couldn’t work for us because of the style of music we were beginning to play — that’s when the idea came to go to Carnival, because in those days, all you had to do was turn up.” In 1987, Shock hitched up at Powis Square, the first house sound system to do so. They soon outgrew that square and were moved to Colville years later, where KKC, another house sound, still plays.

Although now far removed from the conscious reggae world of their elders, Shock kept the dubplate tradition, essential for any sound worthy of its name. Saint even produced his first track, ‘Give Me Back Your Love’, for the sole purpose of playing it out as a dubplate. The sound found a home in venues up north, where acid had already made inroads, and the legendary Clink Street, with Ricardo Da Force (of KLF fame) and Shamen frontman Mr C as their MCs. Paul Oakenfold, Nikki Holloway, Boy George and S’Express’ Mark Moore all made an appearance at one time or another. “I wasn’t there for reggae or punk, but from what I’ve heard about it, in terms of how there was a connection between the reggae and punk parties in the late ’70s, to me, that was what was happening with house — it was bringing together all different types of people.”

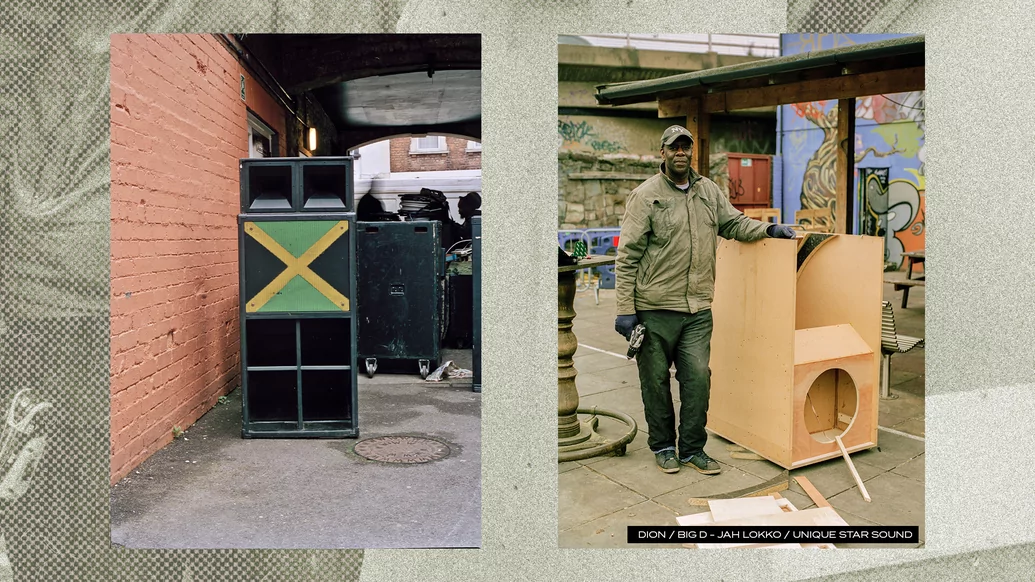

Over in Bristol, sounds such as Enterprise, Iquator, Jah Lokko (which would later become known as Unique Star Sound), Raiders 32 and many others were strong on the roots and reggae scene. But a new style of sound was coming into play, chief among them, The Wild Bunch, which laid the ground for the trip-hop generation. Miles Johnson, aka DJ Milo, Nellee Hooper and Grant Marshall, aka Daddy G — of Massive Attack fame — spent the weekends listening to reggae, punk and new wave records before their sound came to life. The trio, which gathered a crowd for these informal listening events, were beginning to outgrow Marshall’s home, so decided to rent out a room in a pub just off Queen’s Square in the city centre.

The crew started out with a large and varied record collection, one turntable, a Realistic mixer, and a few amps, later upgrading to a GLI PMX 9000 — the first mixer with a crossfader. They played random pubs and house parties, and finally, outdoor events, growing in reputation from the Downs in Clifton, Bristol’s middle-class neighbourhood, to St Paul’s – “the Brixton of Bristol”. A dread from St Paul’s named them. “When we played St Paul’s, that was setting the standard for us,” Johnson tells DJ Mag. “We knew we were running up against Jamaican sound systems, so we had to run with something that was going to be heavy, otherwise we would get drowned out. We always came correct.”

Like any other Bristol sound system, they had their versions, a deep reggae collection courtesy of Marshall, and even indulged in the well-worn practice of labelling-out records. But it was the lively concoction of hip-hop, punk and new wave records that stood this crew out. They played UK DIY artists PiL, Jah Wobble and Delta 5, Brit funk numbers by Touchdown and all the early hip-hop cuts they could get their hands on. The MC line-up also grew, with 3D (Robert Del Naja) joining for regular gigs, followed by Willy Wee (Claude Williams) and later on, Tricky. “Because of the time we were born in and the social integration, it created something unique,” Johnson explains. “We were doing what was natural for us — there was no ulterior motive. It was filling a necessary void, it was more of a spiritual thing.”

A turning point came when the group laid their hands on a copy of the Wild Style soundtrack, a film widely held as the first hip-hop motion picture. “Everybody in England was blown away by it and how familiar it was to what we were experiencing in blues dances,” Johnson remembers. “That familiarity was something we could hold on to — the way they were presenting the music, that heavy bass, was exactly how we felt was the best way to present what we were playing.” Hooper flew to New York and got hold of a reel of the soundtrack, which wasn’t out on general — or limited — release. It was a canny move. “If a lot of crews didn’t respect us before, that really put people in a different mindset, especially in London.”

It’s early August and the Kallida Festival in north Devon is in full swing. Mark Iration, of the legendary Leeds sound Iration Steppas, is delving deep into the early Warp catalogue. At around half 9, he drops a rewind of LFO’s ‘Aftermath’ remix and the crowd, a small-but-dedicated extension of the Kallida crew network, roars with approval. “Dem kinda festivals me can play all tings,” Iration booms down the mic. “Me have every ting.” His audience, of predominantly English millennials, is a far cry from those he used to play to when Iration first began.

“It was a Black culture and then in the ’90s, it started to spread out. Now it’s massive, it’s all over the world now. We have woken people up to love and this sound system culture,” Iration tells DJ Mag weeks later. And he should know, having toured Colombia, Canada, Brazil and Mexico alone this year. No one would have predicted such a career for sounds back in the mid-’80s. “I was just a young man watching the elders,” Iration shares in a patois-leaning Leeds cadence. “I was buying music in Leeds, Manchester, London — back in the days you had to drive, catch a train, catch a coach, meet somebody to get the music.”

Encouraged by the elders to build his own sound, Iration set up Ital Rockers with Sam Mason, which played across the board — rocksteady, lovers rock, hip-hop, soul, dub, house — and made classic records such as ‘Ital’s Anthem’ and ‘One Day’. Iration Steppas — a strictly dub affair — was birthed at the tail-end of the ’80s and hosted the famous SubDub nights at the Leeds West Indian Community Centre. “Anybody who’s anybody right now — Mala, Skream, Benga, Hatcha — all of them guys were introduced to SubDub.”

But when jungle hit the scene, dub struggled to compete. Iration, Aba Shanti-I and Jah Shaka kept the dub flag flying, while many others had left the scene. It wasn’t, however, just the arrival of a new genre that weakened the sound tribe. The crackdown on DIY parties and outdoor raves was forcing revellers into clubs and these venues were eschewing sound bookings for installed PA systems.

“We couldn’t take big double boxes into venues anymore,” Dread says. “Everything was turning into a discotheque, they basically pushed out the sound systems. That’s when the PAs started coming around. If it wasn’t for sound systems they wouldn’t have all these basses.” Channel One kept afloat by trading in its seven-foot scoop bins for smaller speakers, and kept on the student circuit.

"Our sound system got stolen,” Saint shares, “and the reason it got stolen was because it wasn’t getting used and the reason why it wasn’t getting used is because, in the genre where we made our name [house], our sound system had become redundant. People didn’t want a team of six DJs and a sound system. It was becoming commercialised.”

“Sound systems are the hardest workers in the business. You’ve got to make sure everything’s right for the artists, the DJs, the MC, then wait for people to leave the dance, string down the sound system, drive back home, unload the sound system, take the van back to the van place, wherever that is, then get to our bed. And then we do that the week after or the day after.” – Mark Iration, Iration Steppas

While a number of sounds fell by the wayside in the early ’90s, Nzinga Soundz was just getting into its stride, impressive for a sound system that’s never been one for promotion. June Reid, aka Junie Rankin, and Lynda Rosenior-Patten, aka DJ Ade, begin our Zoom conversation by paying respect to the women who came before them: Ranking Miss P, the first Black female presenter at BBC Radio 1 to have her own specialist show, Sista Culcha, who ran an earlier sound, and Soul Seduction, the first and at present only female-led system at Notting Hill Carnival. They also mention newcomer Sisters In Dub, a female trio sound based out of Coventry.

Taking their name from the 16th-century Angolan warrior queen, Reid and Rosenior-Patten established Nzinga in the mid-’80s. They attended the same secondary school and university, and on graduating, even landed jobs at Virgin Records, the biggest music retailer in Europe at the time. Rosenior-Patten became the head buyer for the reggae, soca, Africa and world music sections and together the pair used their knowledge and access to build up a record collection most would envy. In the 30-plus years they’ve been around, Nzinga has supported legendary reggae and rocksteady acts such as The Mighty Diamonds, Burning Spear and The Heptones, and played as far as Sierra Leone, The Gambia and Barbados: they’re more than likely the longest-running all-female sound system in the UK.

The pair never started out with the intention of becoming an all-female sound, but they noted early on how disruptive their presence was at dances, what Rosenior-Patten has often described as a “coded-space”. "There was no room for failure,” she tells DJ Mag. “You just have to deliver. In most cases, I’d have to say we over-delivered, because that’s what was at stake, our reputation, our standing.”

The early sound systems come from humble beginnings – gear was either passed on from one family member to another, or slowly built using material bought or borrowed. Valve, the world’s first drum & bass sound, was anything but that. Kevin King, aka Lemon D, and Karl Francis, aka Dillinja, were established names in the d&b scene when Valve emerged as an idea. The pair’s ambition was to fashion a sound system with the same sonic clarity you’d find in a recording studio, separating the high bass and low bass to ensure a punchy kick and a clean low-end. The research and development phase — meetings with speaker builders, component builders, designers — lasted a lot longer and cost more money than expected. “Karl was even in talks about bringing a speaker developer on board, someone to work full-time designing drivers,” King explains, a little exasperated. “There was a lot of money spent developing designs but they were not to our standards, we got to the stage where we were building stuff with our own hands.” The project, which they financed with the sale of their homes, ran them well into six figures.

With just a week to go till the sound system’s debut at fabric in 2001, and far from finished, Dillinja decided on a drastic move. “By that Monday we knew we weren’t going to make it, so Karl locked us in the warehouse — we all agreed to it. All I saw was the sun rise and the sun go down. By the third day we all got cabin fever. It was tedious.”

The crew lived on coffee, working through the night, soldering on (pun intended), right up until the day of the debut. They were still building hours before the launch and had just an hour to assemble the first iteration of their system. It proved worth the wait. “People were blown away by it. That was the catalyst for us to take the sound system to where we wanted to. Every penny that we earned would go into the next stage of the sound system.”

Pegged as the only drum & bass sound system in the world and boasting 96KW of power, Valve drew audiences the world over — top-tier DJs even offered to play their events for free, though King won’t give names. He does, however, share panic-inducing moments, like when one of the two 7 ½ tonne lorries carrying the sound to a gig broke down on the motorway, or a New Year’s Eve event at KOKO, when a punter failed to make it to the toilet on time. “The bass must have rumbled their guts,” he tells us, ”they just basically shat on the dancefloor and we only realised at the end of the night when the club goers had left the venue. You could see faeces spread all over the dancefloor.”

After over a decade touring the country and on the university circuit, Valve was shelved in a lockup. The audiences weren’t what they used to be, plus King and Francis were nearing a burnout. “People don’t realise you’re setting up a huge sound system and then putting it in a lorry and driving down the motorway and doing it all again.” It’s a point echoed by Iration. “Sound systems are the hardest workers in the business,” he says. “You've got to make sure everything’s right for the artists, the DJs, the MC, then wait for people to leave the dance, string down the sound system, drive back home, unload the sound system, take the van back to the van place, wherever that is, then get to our bed. And then we do that the week after or the day after.”

One sound bucking the current trend, however, is Black Obsidian Sound System (B.O.S.S), founded in 2018 by a community of queer, trans and non-binary Black and people of colour. The brainchild of a handful of London-based artists, DJs, engineers, barbers and activists, B.O.S.S debuted at a Gasworks art installation and has since gone on to host parties, community events and feature in other exhibitions.

And of course there’s Kamala, who’s lining up new recruits for Carnival next year’s programme. She’s also scheming a new sound of her own, inspired by the number of women she was able to share the stage with this year. “As I’m talking to you right now, I’m loading up my car with my sound system. This is the dedication. I don’t know how much longer I can keep going, because it’s a very physical thing, but it’s just in you. People love it, and I guess I’m one of them.”

Listen to Sisters In Dub's exclusive mix for DJ Mag below.

Tracklist:

Aza Lineage ‘Owa Sound’

The Meditations ‘Judas’

Iration Steppas ‘What’s Wrong’

Yaksha meets Fikir Amlak ‘Overcome’

Moa Anbessa ft Prince David ‘Jah Fire’

Jalifa ‘Hear Ye’

The Emetarians - Hardest Thing To Say’

Xana Romeo ‘King of Zion’

Kushite ‘Stand Firm’

Jah 9 ‘Highly’

Queen Ifrica ‘Predators Paradise’

Protoje ‘Self Defence’

Dennis Brown ‘I Don't Want To Be No General’