The house music boom of Chicago's sock hops: an excerpt from Emma Warren's Dance Your Way Home

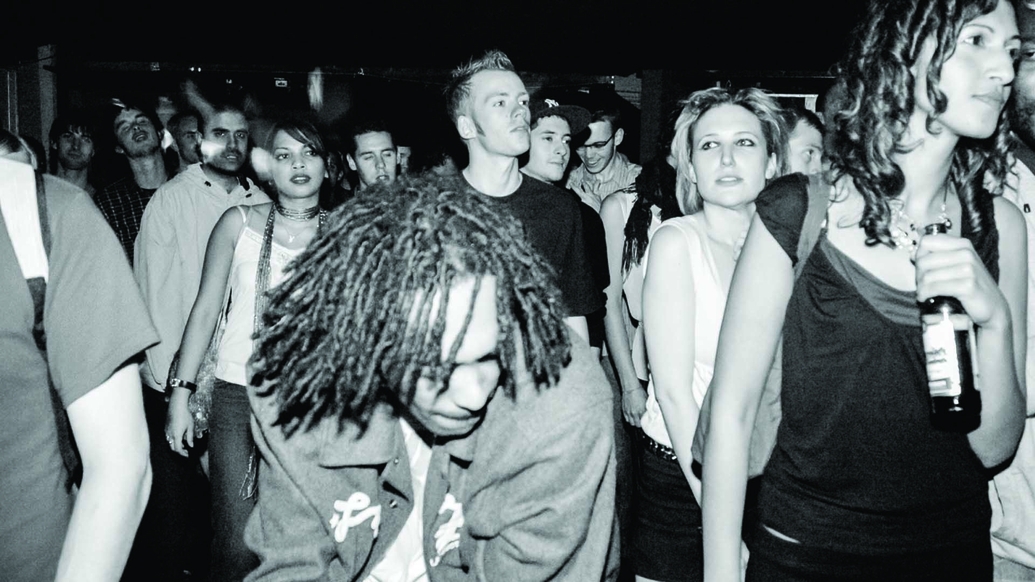

Dance Your Way Home is a new book by music and culture writer Emma Warren. Subtitled ‘A Journey Through The Dancefloor’, Emma travels through a number of different dance spaces over time — from school discos to the fiercest drum & bass raves, and many places in between — to focus on a set of people who have often been left out of dance music history. Here, we run an excerpt from the book that Emma picked out for DJ Mag that focuses on how house music grew at Chicago's sock hops

School dances, or ‘sock hops’ in the gradually disappearing terminology of the 1950s, were standard fare across the U.S, although Mendel High students in the early-to-mid 1980s had access to unimaginable levels of musical excellence; the dance music equivalent of having Jean-Michel Basquiat drop into your after-school art club, or Serena Williams cover Friday afternoon PE. Mendel was a popular boys’ only fee-paying Catholic High School located at 111th and King Drive in the historically Black area of South Side Chicago and the city’s best DJs played at the school’s Bi-Level parties. These included Warehouse resident Frankie Knuckles, Ron Hardy, and the city-famous Hot Mix 5 DJs, who reached a million listeners a week. A flyer from September 1986 has a headline — Ron Hardy Strikes Again At Mendel Bi-Level — plus a short note from the DJ himself (it reads: ‘I will be jacking you at Mendel’) and a tagline ‘come ride the rhythm’.

The presence of house music’s originators at Mendel’s Bi-Level dances prepared large numbers of young Chicagoans from a range of backgrounds to amplify and strengthen the interconnected networks of juice bars, rollerdiscos and front room house parties that built house music as a genre. They bumped it out of one locality and into a global genre that is still living and evolving decades later. Part of the reason house grew is the presence of the physical space in which thousands of very young people could experience and share the music in a safe facsimile of the adult environment. These circumstances gave young people ownership of the culture, not least because it was happening in their school. House music wasn’t being presented to them as a finished thing for them to purchase and consume. It was incomplete and therefore able to absorb whatever they wanted to bring to it: a new sound, dance, or way of dressing — or just their complete attention, in the moment.

Ron Trent is a prominent DJ, producer and artful dancer who grew up a few blocks from Mendel High School. By about 1986 his 14-year-old self was attending Bi-Level dances and soon graduated to DJing in the basement cafeteria. He continues to make beautiful music and is at the time of writing, collaborating with Robert Williams on the Warehouse founder’s history of Chicago clubs. He’s a very funny man, prone to looming towards the screen to lighten another insightful point with a facial expression or gesture and a baritone chuckle. ‘The music of the day, for the cool kids, was the soundtrack being created by Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy,’ he explains, adding that Mendel was known as ‘top tier’. ‘The culture, the kids that went to that school, it kind of spilled out.’ This expansion from necessarily niche beginnings to events catering to a wide range of teenagers represented what he describes as a ‘coming of age’ for house music. ‘The culture was starting to spin out to the heterosexual community — [before] it had mainly been gay.’

Highly skilled dance crews were also part of the mix, although their era of dominance was fading by this point. There are whole other books to be written about this aspect of Chicago’s cultural life, but for the purposes of this story it’s just important to know that they existed and were important. The rise and spread of house music — and the sheer numbers swept up in its addictive and sensual grooves — meant that people increasingly moved how they felt within the basic movement language of the music rather than the choregraphed brilliance of crews in matching t-shirts. House music suggested, requested even, that you come as you are. This was even true for the crews as they adapted to the new sounds. Jose ‘Gringo’ Echevarria told the story of his Latin dance crew All Stars and their rivals Zoolitos and Tasteful Dancers in The Real Dance Fever. ‘House music was doing well and underground music was everywhere,’ he wrote. ‘If you wanted to dance to good soulful house music you went to the Power Plant, Music Box, or Liar’s Club. There were so many clubs, since the creators and inventors of underground house music, the music we loved, were in Chicago. It was raw, soulful and very expressive. You could say what you wanted to say and dance to what you wanted.’

‘I belonged to one, voluntarily–involuntarily,’ says Ron Trent, of the dance crews, communicating the essence of the situation through the medium of raised eyebrows, ‘because they inducted me. I will spare you the gory detail.’ It was, he says, very eccentric. ‘These dance crews had their own style that set them apart; their own dances that they did, that were kinda seminal to the underground ethic which was more the idea that we get on the dancefloor and we express ourselves. There may have been some dances [like] jacking, but everything else was freeform. The idea and the concept was being developed.”