How is the cost-of-living crisis hitting UK nightlife?

Post-pandemic, as UK clubs have attempted to regroup, they’ve been impacted by soaring energy bills, rising costs and hesitant ticket buyers. Jack Ramage talks to club owners and promoters about how they’re weathering the storm, and asks what can be done to ameliorate the situation?

“It’s terrifying... I wake up every day and hope that we find a way to keep going,” Kate Hodgkinson, co-founder of Cobalt Studios, an independent 220-capacity venue in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, tells DJ Mag. “We’re just trying to keep our heads above water. You just have to do what the shit mugs say: keep calm and carry on.”

Her views are echoed by club owners across the country. As the cost-of-living crisis bites, expenses across the board are skyrocketing. While the media has pointed its lens on the impact energy hikes are having on domestic households, with 1.3 million people across the UK expected to slip into poverty this winter, the music scene is fighting a battle of its own. With the residual effect of the pandemic, paired with rising bills, inflation and economic anxiety, it’s a perfect storm — and venues are now finding it challenging to stay afloat.

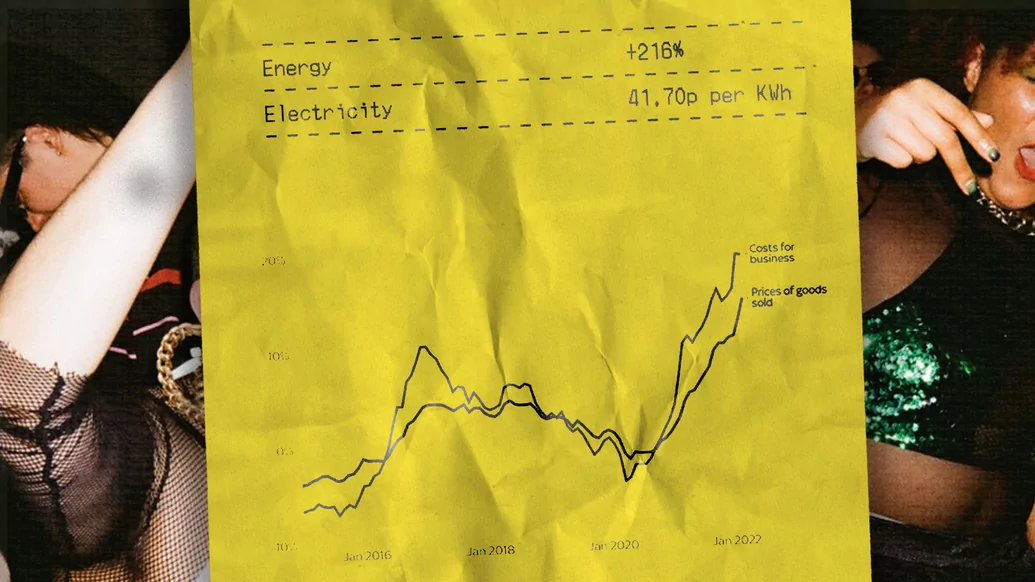

“I don’t really look past six months anymore,” Jake Farey, founder of Peckham Audio, another 220-capacity venue in South London, says. His energy cost has seen an increase of 216% since June — with his electricity bill rising from 13.16p per KWh to 41.70 per KWh in October.

“You just have to keep your cards close to your hand and get through it,” he continues. This is an issue that impacts small and large venues alike. But what does this mean for the music business as a whole? Is this the nail in the coffin, or yet another blip that the industry will, through sheer grit, overcome? To understand the reach of this crisis, it’s important to look at how it’s affecting the very people that keep the scene turning: clubbers.

“The culture of buying tickets has changed enormously,” Hodgkinson argues, noting that ticket sales to club nights have been “very erratic” since the cost-of-living crisis hit. Despite her recent club nights selling out, the vast majority of tickets are only sold on the day of the event. “It’s anxiety-inducing, I’ve had to turn notifications off my phone and hope for the best,” she says.

This is an observation repeated by all the club owners and promoters who DJ Mag spoke to. Jake Farey from Peckham Audio adds that, before the cost-of-living crisis, he’d see a pattern of “progressive ticket sales”. But recently, “that behaviour has changed — now more people buy tickets just before turning up. That’s the path the industry is going on at the moment. It’s not healthy for the scene to know that you’ve sold only around 50%-plus of tickets before the day of the event,” Farey says.

Tom Burnside, programmer and events manager at Lakota in Bristol, suggests the change in ticket-buying behaviour could also be attributed to the pandemic. “The behaviour of young people has changed; people generally don’t seem to be going to clubs as frequently as they did before. This is the first season where the pandemic hasn’t really impacted us directly — [but] we’re starting to see the different effects Covid has had on the scene.”

There are, of course, parallels between the pandemic and the economic pressure we face today. “The pandemic forced everyone into a fear response — now the rising cost of living is doing the same,” Hodgkinson agrees. “People are frightened to buy things in advance because they don’t know what’s going to happen next. Although people do end up eventually coming to Cobalt Studios — especially because we have a focus on our tickets being affordable — it’s pretty horrendous not knowing if we’re going to sell enough to break even.” This behaviour is backed by Patrick Fagan, a consumer psychologist at Goldsmiths University, who noted that people are “much more risk-averse” in times of economic hardship.

“[Club goers] might not want to pay today for [an event] in the future, because it feels risky. This is a bias called future discounting; we want pleasure today and pain tomorrow, and since people rely on biases more under uncertainty, we’re likely to see more of this behaviour.”

Keep Hush, a community-driven underground dance music platform that runs regular events across the UK, conducted a survey on the scene back in May 2022, highlighting the stress the current cost-of-living crisis — as well as the pandemic — has put on the industry. According to its findings, 25% of Gen-Z respondents and 13% of millennials reported being less interested in clubs now than they were before the pandemic.

The survey also found that clubbers now are less likely to buy tickets in advance. According to the findings, 24% of Gen-Z and 31% of millennials were less likely to buy tickets to events prior to the day of the event, compared to before the pandemic hit. The survey concluded that promoters should adapt to this new behaviour to “make the most of ravers’ last-minute mindset”.

Despite the ongoing impact this crisis is having on our finances, the survey also found that ticket prices were not an indicator for people when choosing what event to go to — with people naming flexibility, and not planning too far ahead, as of greater importance.

“For us, we have a hunch that people will still go out, but probably fewer times a month. When people do go out, they’ll probably choose more carefully what events to go to,” Andy B, chief marketing officer at Keep Hush says, noting that the ticket price isn’t the only cost people have to factor in — the price of drinks or transport may have an influence as well.

“We really need to be constantly busy to be sustainable and carry on — we’re sustainable at the moment, but there’s a lot of competition too” — Jake Farey, Peckham Audio

A decrease in bar sales and increase in drink prices have raised concerns for those running events. “Even at sold-out events, arrival times for clubbers are later and bar sales are roughly 25% lower,” Harry James, promoter at The Lower Third, a new 250-cap venue in London, tells DJ Mag. This can be detrimental, given that alcohol sales are often the driving factor for small clubs to break even — particularly as other costs like energy and bookings rise.

This is a worry shared by Farey, who notes that bar sales at Peckham Audio have slightly declined over recent months. “Even when we’re still getting a decent amount of attendance, people aren’t spending as much at the bar as they were before,” Farey says. “We really need to be constantly busy to be sustainable and carry on — we’re sustainable at the moment, but there’s a lot of competition too. September and October are usually our best months — we are doing well, but it hasn’t been as fruitful as other years.”

The cost of manpower has increased too, putting further strain on clubs. “Venues are increasing their fees to cover raises in wage costs. Particularly in London, where the cost of living is higher, the standard minimum wage isn’t enough for the working-class. London minimum wage is absolutely necessary,” James adds.

This is a situation playing out across all small venues, even those residing outside of London. Hodgkinson stresses that meeting the demands of wages for her employees at Cobalt Studios is something “that is really important” and that “until recently” they have paid above minimum wage. “Politically and ethically, I absolutely agree with wages going up, but for a small business, it’s hard to keep up with,” she says.

The damage of rising prices isn’t isolated to clubs and promoters, either — independent radio shows have also taken the brunt of the blow. Just recently, Gilles Peterson’s Worldwide FM announced it would be pausing its broadcasting in October after six years as it enters a “period of transition.” In September, SWU.FM in Bristol stopped its operations, citing financial issues and energy bill hikes as the cause. Independent radio stations are particularly at risk of the impact of rising prices, Andy B notes.

“It’s very difficult to make income [as a radio station], because a lot of the time, it requires a physical space. It’s not a commercial space either, like a club, which leaves them vulnerable to energy hikes. It’s not like they can up the drink prices or charge more on the door.

“Less radio is generally bad for the music industry: it’s one of the main tools for discovery among the underground electronic dance music scene,” Andy B continues. “Some say the market is oversaturated, but the more the better, I think. The more radio stations there are, the more opportunity there is for up-and-coming DJs to have a platform and develop, which is a great thing.”

“It’s going to be tough for the scene to adapt, but I think what we’re going to see is that the industry will become resident focused” — Tom Burnside, Lakota

Albeit limited, there are positives the cost-of-living crisis could have on the industry, too. One of these few benefits is that scenes could source more local talent to put on events — causing local communities to thrive as a result. “As DJ fees, travel and hotel prices have upped, promoters are being squeezed from both sides — they’re the middlemen taking the gamble,” Farey notes. “I do imagine the industry going more local and DIY.”

Burnside agrees that current price hikes will force scenes to develop on a more local level, sourcing regional talent instead of from further afield. “It’s going to be tough for the scene to adapt, but I think what we’re going to see is that the industry will become resident focused — finding talent where they are, which could be really good for the scene,” he adds. “I think that an increased interest in local talent is a positive,” James says, noting that the most successful nights he’s recently put on have been showcasing regional DJs. “Lower-cost local events are the only ones that have been a touch improved on — in my observation at least. Things like £5-entry nights, with a good collection of DJs from the local scene who have a loyal following, seem to not have been as affected by all this.”

There is an argument that rising costs, for clubs and the clubber, could mean music scenes venture out of clubs and into DIY spaces entirely — sparking a new free party and illegal rave movement akin to the Second Summer of Love. “I do see that being a possibility — the anarchist and ‘90s kid in me really hopes so,” Hodgkinson says, drawing attention to the illegal rave boom we saw in lockdown.

“On the flip side, however, I feel very passionately that when we open our doors there’s a whole team of people to help vulnerable people and look after them,” Hodgkinson continues. Moreover, a thriving illegal rave scene could mean vulnerable people are put at risk. Take, for instance, the free party that took place in Manchester during lockdown which led to one death, one sexual assault and three stabbings. Traditional venues allow for “systems to be put in place”, ensuring the safety of clubbers, and for “people to enjoy themselves”, Andy B adds. “In a free party scene, that kind of thing is probably non-existent, or less likely to be enforced.”

Free parties are not immune to energy price hikes either, Burnside notes. “There’s also the obvious risk that your equipment will be seized by the police. I do think there will be some kind of counter-culture, however: people will use parties as a stance against the economic climate and the government.”

So what has the government done to soften the blow? On 21st September, the government announced an energy bill relief scheme in a bid to take the pressure off businesses, charities and public sector organisations for the next six months. The scheme, which proposed a base unit rate of £211 per MWh of electricity and £75 per MWh for gas has been tentatively embraced by some, with the Music Venues Trust announcing it would be “sufficient to avoid the collapse of the sector” in the short term. Others, including Jake Farey, argue that the scheme doesn’t go far enough.

“I’ve had around £400 back from the government to last for the next six months, what’s that going to do to help in this current climate?” Farey asks, highlighting that council business rates are putting a lot of stress on all venues. “I think, unfortunately, there will be club closures as a result. We’ve had two years of the pandemic, we’ve just got back on our feet, and now we’re faced with more uncertainty. There will also be people willing to make things happen — maybe in unique spaces — but there needs to be a change in business rates to really benefit music venues.”

Lowering the VAT rate for tickets from 20% to 5%, similar to what was done during the pandemic, would also “take a lot of pressure off promoters. It would give us the ability to pass on the money made, and be riskier in terms of what we’re doing,” Andy B argues.

Speaking on behalf of smaller venues, Hodgkinson notes that those in power should recognise the diverse and nuanced nature of club culture — how not every venue is the same, and how grassroots venues have different financial models. “In terms of tax, the government should consider smaller and independent venues [differently] from the huge clubs we have to compete against. They need to see us separately from capitalist organisations.”

UK club culture is on somewhat of a precipice; it’s clear drastic action is needed to prevent widespread damage to the industry. This is a nuanced and complex issue — affecting all aspects of the music scene, from venues to radio, DJs and clubbers themselves. However, despite the doom and gloom, there is room for positivity. This could be an opportunity to turn a corner, for the government to give the music industry the support it deserves. However, for that to happen, “the government needs to recognise the nightlife industry as an incredibly important part of our cultural economy,” Hodgkinson argues. “They need to know the true value of having exciting, innovative clubs in our society.”