How Drexciya's 'The Quest' embedded the Detroit act's mythology in dance music history

Released in 1997, Drexciya's double-vinyl compilation 'The Quest' marked the duo's breakthrough onto a larger public stage, as well as their first, temporary, retirement. With liner notes that sharpened their Afrofuturist mythology into focus , it is also the record that cemented many fans' sonic liaison with the Detroit duo, following a series of 12" releases that perfected their musical ideas. Here, Ben Cardew reflects on a record that most perfectly encapsulates the style, grace, and range of James Stinson and Gerald Donald's project

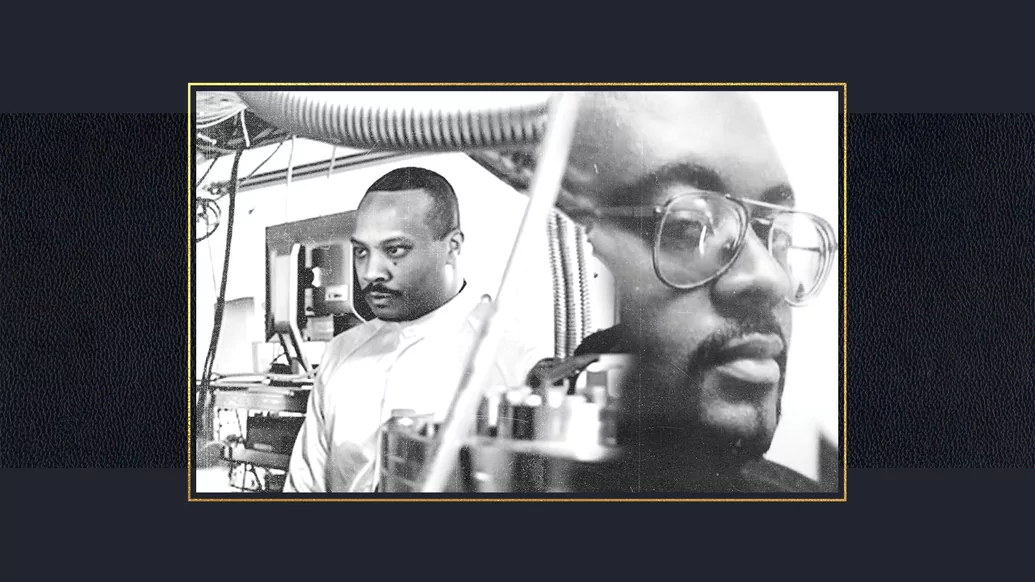

Detroit duo Drexciya were electronic music’s ultimate world builders and myth makers, a production unit whose exquisite musical control was tied to a profoundly moving, thought-provoking legend, in a conceptually brilliant work of modern art. Drexciya’s music was never knowingly abstruse, yet there was something profoundly unknowable about the band, who gave few interviews during their decade of existence, ending in 2002 when James Stinson (half of Drexciya, alongside Gerald Donald) died of heart complications at the age of 32.

Even the most knowledgeable of Drexciya scholars — and there are a few — can’t agree on what albums comprise the ‘Storm Series’, a run of LPs released between 2001 and 2002 under a variety of different artist names that might (or might not) lay out the Drexciyan mythos. But somehow this unknowability only draws the listener further in, like the breadcrumb hints in Twin Peaks or the fractured narratives in James Joyce’s Ulysses.

The physical facts behind Drexciya’s existence, as we know them, are not that different from the origin stories of many Detroit techno producers. Stinson and Donald met at Charles F. Kettering Senior High School, with Stinson, the older of the two, becoming something of a mentor for Donald. Stinson had been introduced to electronic music in the early 1980s by Cybotron’s astonishing electro classic ‘Alleys Of Your Mind’, with his nascent interest further fed by the influential Detroit radio DJ known as the Electrifying Mojo.

The concept for Drexciya apparently came to Stinson during an unsettled night. “One night I could not sleep, cold sweat, tossing and turning, and around 3am, September 18, 1989, I stood up and said, ‘Drexciya’,” Stinson told John Osselaer of Techno Tourist in 2002. “It felt like a tidal wave rushing across my brain.”

Inspiration may have come in a wave, but Drexciya was not for rushing. Stinson and Gerald spent the next three years perfecting their musical ideas before unleashing the debut Drexciya EP, ‘Deep Sea Dweller’, in 1992, its sharp-but-fluid electro-techno style creating a quiet sensation. Over the next five years, the duo released a series of 12”s with titles that hinted at underwater legends: ‘Deep Sea Dweller’ was followed by ‘Bubble Metropolis’, ‘Molecular Enhancement’, ‘The Unknown Aquazone’, ‘The Journey Home’, and ‘The Return Of Drexciya’.

There were other hints, too, that there was a lot more to Drexciya than just music. ‘Bubble Metropolis’ kicked off with a voice giving the enigmatic instruction: “This is Drexciyan Cruiser Control Bubble 1 to Lardossian Cruiser 8-203X, please decrease your speed to 1.788.4 kilobahns”; ‘Wavejumper’ featured a strained tone proclaiming, “You must face the power of the black wave of Lardossa before you become a Drexciyan Wavejumper”; and the ’Deep Sea Dweller’ 12” had “TECHNO FROM THE DEEP” etched onto one side of the vinyl and “DEEP H2O” on the other.

‘The Quest’ marked both the group’s coming out on the larger public stage and their first, temporary retirement. In 1997, Submerge, the Detroit company that distributed many of the city’s key techno releases, issued double-vinyl and CD versions of ‘The Quest’, rounding up a selection of tracks from the group’s EPs and adding a small dusting of new material. For Drexciya fans, it was an almost spiritual release to find their music collected, at a reasonable price, in their local record store.

Even more fascinating were the sleeve notes, the work of The Unknown Writer, widely assumed to be Underground Resistance label manager Cornelius Harris. These, for the first time, made the Drexciya myth explicit. “During the greatest holocaust the world has ever known, pregnant America-bound African slaves were thrown overboard by the thousands during labor for being sick and disruptive cargo,” the sleeve notes read. “Is it possible that they could have given birth at sea to babies that never needed air?”

The revelation of this Black Atlantis would have been enough to cement ‘The Quest’ a place in dance music history, as the Drexciya legend finally sharpened into focus. ‘The Quest’ was also, for many techno fans who didn’t have the cash to buy expensive import 12”s, the record that cemented their sonic liaison with the Drexciya duo, a chance to bring their music into our homes.

“The classic Drexciya sound is a kind of aqueous electro glide, where the ice-water snap of an 808 meets tough but tuneful synth experimentation that suggests an underwater voyage in a futuristic submarine, dodging hydrothermal vents, ominous shipwrecks and mysterious bubbles.”

More importantly, ‘The Quest’ is the strongest Drexciya record. After reversing their retirement and returning to the fray in 1999, Stinson and Donald would release three excellent albums under the Drexciya name — ‘Neptune’s Lair’ and ‘Harnessed The Storm’ for seminal Berlin techno label Tresor, and ‘Grava 4’ for Clone, the Dutch label that has worked to keep the Drexciya legend alive since the duo split. They also have numerous solo works to their names, with Stinson’s ‘Lifestyles Of The Laptop Café’ album for Warp, as The Other People Place, highly recommended.

However, none of these show the style, grace, and range of vintage Drexciya as ‘The Quest’ does, particularly in its 28-track, two-CD iteration. The classic Drexciya sound is a kind of aqueous electro glide, where the ice-water snap of an 808 meets tough-but-tuneful synth experimentation that suggests an underwater voyage in a futuristic submarine, dodging hydrothermal vents, ominous shipwrecks, and mysterious bubbles.

British-Ghanaian writer, theorist, and filmmaker Kodwo Eshun, who has written extensively about Drexciya, told RBMA that the duo: “would imagine themselves in a submersible at the bottom of the ocean before they would make any music... in this metallic vehicle at the bottom of the ocean with all this pressure creaking down on them and it’s pitch dark and then they would switch on the lights and these jets of light would be like searchlights sweeping across the ocean.” You can hear this nervous aquatic mystery, the mixture of dark and light, on ‘The Quest’ in songs like ‘Antivapor Waves’, ‘Bubble Metropolis’, and ‘Depressurization’.

Stinson and Donald were deadly serious about their work. You can hear a lethal intensity to ‘Quest’ songs like ‘You Don’t Know’ and ‘Aqua Jujidsu’, which is a work of controlled fury and poise, like an aquatic army gearing up for war. At the same time, there were frequent moments of light-heartedness and joy in Drexciya’s music. Intended or not, there is a dramatic, even camp, humour to several songs on ‘The Quest’. The theatrical twists and turns of ‘Dehydration’ could soundtrack a Drexciyan take on Scooby Doo, while ‘Aquabon (Remix)’ has a similar touch, with a ridiculously overblown central synth riff that descends down the scale like Nosferatu slinking down a spiral staircase.

There’s a huge dose of funk, too. Stinson may not have been a club-goer — he told WDET-FM’s Liz Warner in a celebrated 2002 interview that “I don’t go out to clubs or anything because I’m dedicated to what I do” — but you could imagine ‘Intensified Magnetron’ or ‘Aquatic Bata Particles’ soundtracking legions of hip-shaking at basement clubs, with the latter sporting a genuinely lascivious bassline. Stinson also claimed to have nothing to do with Detroit techno, although ‘Intensified Magnetron’ has more than a shade of second-wave Motor City producers like Carl Craig within its astral synth chords, while the drum programming on ‘Aqua Jujidsu’ is reminiscent of the intense drum workouts that jungle producers like 4hero were making on the other side of the Atlantic.

‘The Quest’ helped to further stoke the Drexciya legend, but the group was no longer around to enjoy the spoils. There was one further track, ‘Aquatacizem’, that appeared on ‘Interstellar Fugitives’, a 1998 Underground Resistance compilation where the group was described as ‘missing in action’. The reality was more tragically mundane: In an interview with Richard Brophy for Ireland’s Etronik, Stinson said he had “health problems” around the time, “and to be honest, I became seriously ill. It meant we had to shut things down for a while.”

Drexciya eventually returned in November 1999, when Tresor released ‘Neptune’s Lair’, the group’s first official studio album, which is home to the all-time classic ‘Andreaen Sand Dunes’. Tresor followed this up with a flurry of Drexciya 12”s in 2000 and a second album, ‘Harnessed The Storm’ in 2002, as Stinson and Donald entered a period of wild creativity. ‘Grava 4’, the group’s third and final studio album, was released by Clone in 2002 and is notable for its shift away from aquatic imagery and into gazing at the stars, with song titles like ‘Drexcyen Star Chamber’ and ‘Astronomical Guidepost’. Some people speculated that this shift indicated that Drexciya’s quest was over, or had entered another critical phase. But we will never really know: on September 3rd, 2002, Stinson died, and Drexciya was over.

The group’s almost magnetic attraction has only increased over the years, fuelled by a series of compilations from Clone. The group’s Afrofuturist mythology — borrowed, according to Eshun, from Paul Gilroy’s 1993 book The Black Atlantic: Modernity And Double Consciousness — also sits neatly alongside the artistic visions of modern musicians like Janelle Monae, FKA Twigs, Flying Lotus and, most recently, Kelela, while the rise of the internet has helped to amplify the Drexciya mythology without stripping the group of their mystique.

This is as it should be. In his interview with Liz Warner, Stinson shied away from definitive answers about what Drexciya meant. “It’s not for me to say, it’s up to the listener. It’s the same way it’s been from day one with all the Drexciya music,” he said, speaking about the ‘Storm Series’. When Warner pressed him further about Drexciya’s thematic makeup, he answered: “An infinite journey through inner space, the space within and find the beauty inside.” A better description of the infinite appeal of Drexciya’s work — and of their key album, ‘The Quest’ — would be perhaps impossible to find.