Plastikman's 'Consumed' remains a masterclass in dark, minimalist techno

Brooding and austere, Richie Hawtin’s third album under the Plastikman alias is a minimalist masterwork

When first encountering ‘Consumed,’ Richie Hawtin’s third studio album under the Plastikman name, a normal reaction might be like that of the prehistoric hominids in 2001: A Space Odyssey after they stumble across the alien monolith: scared, awed, and very much aware of the presence of a superpower. Like the monolith, ‘Consumed’ is dark and (almost) featureless; also like the monolith, it’s basically perfect in a way that seems to suggest an unsettling kind of higher intelligence.

Unlike the monolith, though, ‘Consumed’ is (at least on the face of it), the work of a flesh-and-blood human being in the shape of Richie Hawtin, then in his late twenties and still a cult figure, rather than the techno superstar he would later become. ‘Consumed’ didn’t exactly drop out of the sky, either. Hawtin’s two previous Plastikman albums, 1993’s ‘Sheet One’ and 1994’s ‘Musik,’ both took the acid-house sound of squalling 303s and cutting drum machines, eliminated superfluities like the human voice, and encased the results in cavernous reverb; the ‘Concept 1’ run of 12-inch singles in 1996 pushed this minimalism to new levels of obsession, laying the path toward ‘Consumed’ in 1998.

“The ‘Concept 1’ releases documented a year of sonic experimentation,” Hawtin said at the time of their re-release in 2021. “Each month I would record as much music as possible with a strict and limited selection of technology. Gone were the typical ‘Hawtin’ combination of TR808, TR909, and TB303s, which had driven the techno tracks I had become known for under my F.U.S.E. and Plastikman aliases, replaced by a stripped-down selection centered around three Doepfer MAQ 16/3 sequencers and five panels of Serge modular racks.”

Each ‘Concept1’ 12-inch was limited to 2,000 copies, with Hawtin taking full control of every aspect of the package, from design to distribution — which meant that they were as widely heard as the two previous Plastikman albums. But much of the ‘Consumed’ sound, which shocked many Plastikman fans at the time of release, was already present in ‘Concept 1,’ as the acidic burbling of ‘Sheet One’ and ‘Musik’ was reduced to an austere series of squiggles, clicks, thuds, and echoes.

Much, but not quite all. ‘Consumed’ wasn’t just minimal — it was dark in the extreme, a pitch-black excursion into electronic sound that had more tonally in common with Norwegian black metal than Joe Smooth’s ‘Promised Land’ or Hawtin’s own blissful ‘Spiritual High,’ which he released as UP! in 1992. DJ Mag once described the 303 line of ‘Plasticity,’ from the ‘Sheet One’ LP, as having “the physical presence of cathedral reverb,” but ‘Consumed’ felt more in line with the echoes of a dank cellar or satanic coven. ‘Sheet One’ looked off into the wonders of space; ‘Consumed’ contemplated a deep, dark, and possibly poisoned well.

Everything about ‘Consumed’ was stygian, austere, and designed to disorient, an 11-track journey into nebulous space. The basslines, such as they were, were pitched low and menacing, more of a malevolent presence than a musical force; the drums hit like hammer blows to the knees, bearing little or no similarity to the physical kits on which drum machines were based; the synth melodies, when they came, were brief and discomforting, four-note bursts of whistling paranoia; the occasional sound of a 303 was stripped back to tiny fragments, little more than the idea of notes. And all of this was wrapped in a series of chirps, howls, and echoes, reminiscent of a murderous mechanical zoo, everything reduced to the most minimal concoction possible, putting an almost sickly emphasis on the negative space between music and listener.

“‘Consumed’ was recorded in the dead of winter in Canada,” Hawtin told the Line Noise podcast in 2022. “It was very isolated. So I think there is this kind of iciness, this introverted, kind of alone, dark part. Not dark as in necessarily scary, but just it’s very brooding, you know?”

“In its artful reductionism, ‘Consumed’ would go on to influence techno music for the best part of the next decade, as minimal went on to rule the dancefloors, with Hawtin’s Minus label at the forefront.”

Techno music, let us not forget, comes from disco and funk. It’s generally music for dancing. But there was nothing of joyful motion in ‘Consumed,’ nothing funky to grab the muscular attention, no lingering traces of human instrumentation to rescue you from the void. Rather than Larry Levan in the Paradise Garage, ‘Consumed’ felt like Jean-Paul Sartre contemplating endless nothingness in 1940s Paris: bleak but fascinating, and perfect in its intellectual inhospitality. This was by design.

In a recent video, Hawtin said that ‘Consumed’ “is about taking as much away as possible. Leaving something which was more the aftereffects, the shadows of sound... I think at that point, in 1997, I had had so much time on the dancefloor, and ‘Consumed’ was kind of an antithesis of that. It was, ‘Can I continue to make music, coming from a DJ perspective, but reduce the sounds, the rhythm, so that it doesn’t feel like monotonous 4/4 techno anymore?” You could, at a push, dance to some of ‘Consumed.’ But throughout the album, the music feels more like it is waving the possibility of the dancefloor before you, then snatching it away at the last minute.

That this menace was encased, on opening tracks ‘Contain’ and ‘Consume,’ in a shuffling triplet rhythm that was more typical of glam-rock boogie than Detroit warehouses (the kind of rhythm that would later form the basis of the short-lived Schaffel genre) felt like some kind of sick joke on the listener, like a pantomime horse clad in satanic robes or the monstrous rabbit figure in Donnie Darko. Hawtin wasn’t the first techno producer to use this kind of rhythm — Felix Da Housecat’s 1997 Essential Mix for BBC Radio One kicks off with a track listed as Ghetto House ‘Untitled’ that has a triplet rhythm, for example — but it was certainly rare, and Hawtin has to earn credit for helping to pioneer it in dance music.

A hominid-esque fascination was not an atypical response to ‘Consumed.’ Canadian musician Chilly Gonzales, who recently reworked ‘Consumed’ as ‘Consumed In Key,’ initially found his musical sensibility threatened by the album’s loose use of melody and negative space. “Having one part of me that is a deeply conservative musician, who believes that melody played on instruments is still the highest form of music, to hear ‘Consumed,’ to hear the freedom in how it was made, and to hear the confidence within which it stands behind so few elements, was almost like a threat that I had to respond to,” Gonzales explained in a video to mark the release of ‘Consumed In Key.’ Gonzales compares ‘Consumed’ to jazz, a connection that likely hadn’t occurred to many listeners. And yet it turned out that Hawtin was in fact listening to a lot of jazz during 1997 and 1998.

“I wasn’t sure if my jazz influences showed up in ‘Consumed,’ but they were definitely part of the recording process,” Hawtin told Line Noise. “Because, during ’97, ’98, if there were two things that were inspiring me, it was Miles Davis — listening to his music, reading some biographies about his early work — and contemporary art.”

What he took from jazz, Hawtin explained, was “what I was not hearing... I was listening to Miles and I was very interested and inspired by when you felt like there was a lot going on, but there wasn’t,” he told Line Noise. “There were actually things that weren’t there anymore. You’re nearly hearing things that Miles wanted you to hear but he actually didn’t put in: this idea of space and notes that are missing. And that was very much what ‘Consumed’ was about. You don’t hear the 303s or some of the melodies, they’re just washed-out. And they’re just the afterthought.”

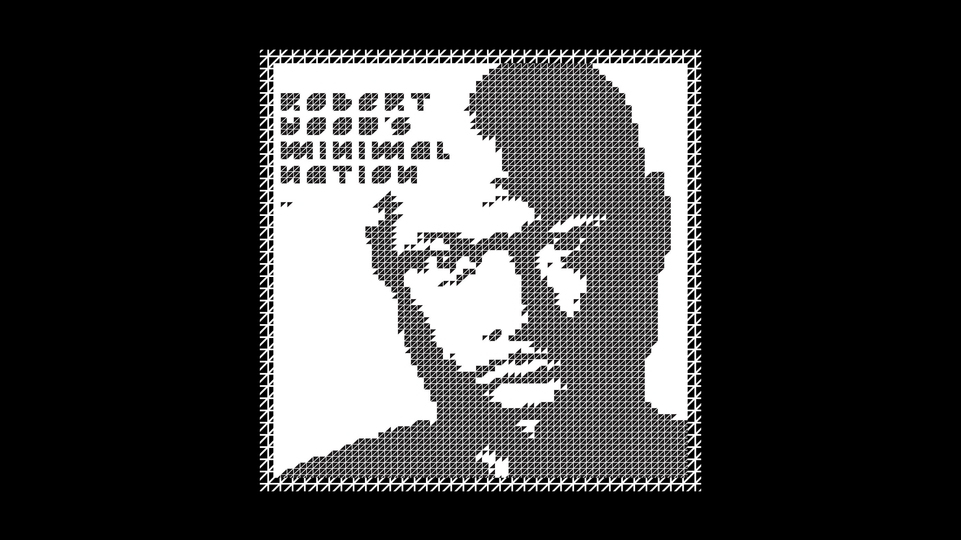

In its artful reductionism, ‘Consumed’ would go on to influence techno music for the best part of the next decade, as minimal went on to rule the dancefloors, with Hawtin’s Minus label at the forefront. This electronic flattening may seem a rather unfortunate legacy for such a brilliantly adventurous album. But, much like Robert Hood before him, we can’t blame Hawtin for his weakling imitators, who took on the minimalist spirit of ‘Consumed’ without ever getting close to its heart. Released a decade on from the birth of techno, ‘Consumed’ is like everything your mother ever warned you about electronic music — dark, druggy, nasty, cold, and terribly addictive, it’s a record that deserves to be admired under lock and key; not so much solid gold, as Vantablack.