Quality time: the new era of hi-fi listening bars

Audiophile sanctuaries for a premium auditory experience, listening bars — or hi-fi bars — are increasingly common in the UK and Europe. They prioritise a top-notch sound system and equipment, but increasingly differ from their Japanese forerunners. Ria Hylton learns more

This feature was originally published in DJ Mag's May 2024 print edition, shortly before JAZU announced that it would be leaving its Peckham venue. The team have now revealed they will be opening a new space in South East London this summer. Learn more here.

South London’s JAZU belongs to a new generation of hi-fi audio bars. Inspired by the kissas of Japan, the venue boasts a purpose built sound system, designed to scale over time, with elm horn speakers, state-of-the-art drivers and a thunderous subwoofer that doubles as a lightbox. In the day it serves coffee and at night classic cocktails, alongside music from the owner’s personal record collection.

But when DJ Mag arrives one Saturday in March, Kay Suzuki is behind the decks spinning zouk, reggae and other 12-inches from his bag. Friendly faces greet us from behind the low-lit square bar which, we discover days later, belong to the owners. “We were really interested in trying to create this kind of quality that runs through each part,” JAZU boss Rosie Robertson tells DJ Mag, “trying not to drop the ball on any element, that was our wish for the space.”

The earliest kissas were listening cafes with high-end stereo systems run by jazz collectors, where records were played in silence, beginning to end. They grew in number over the decades, peaking in the mid-'70s, before dropping out of fashion. But now the concept has gone global. From Northern and Central Europe, to North America, Southern Africa and Oceania, hi-fi bars are all the rage. Though often cited as listening bars in the Japanese tradition, visits to a number of venues and talks with people in the audiophile field suggest this label might be a bit misleading. True, the speakers are high-end and lovingly kept, but that reverence for sound and a deep listening experience doesn’t seem to translate. How to explain this kissa-adjacent phenomenon?

“They had a really cool, relaxed feeling, the same thought that had gone into the music set-up had gone into the drinks and atmosphere” – Rosie Robertson, JAZU co-owner

Club venue numbers in the UK have dropped by nearly a third since 2010, a decline steeper than bars and pubs. The trend now, say experts, is to invest in quality experiences. Dwindling are the regular mid-week club night outings and on the rise special, albeit more expensive outings. Enter botanic beers, organic wines and high-end sound systems. Robertson proffers another idea. “Without going too pop psychology, I guess post-pandemic people kind of have to have a reason to leave the house, so you have to offer something they don’t have at home.”

JAZU’s co-founders decided to open their own space after discovering sound bars in Mexico, like Chihuahua’s Café de Nadie. “They had a really cool, relaxed feeling, the same thought that had gone into the music set-up had gone into the drinks and atmosphere,” Robertson remembers. Japanese kissas were also a key reference, but the trio were conscious of making a space that fitted London — talking would be allowed. “I guess these things make sense in a certain place and time but it just felt that translating the ‘no talking’ bit would be beyond pretentious,” she laughs. “I guess it was about trying to find this balance between taking these things seriously and offering a high-quality audio experience in a friendly, unpretentious atmosphere.”

They kept the set-up simple, analogue throughout with a MasterSounds two-channel rotary mixer and effects unit, and inbuilt amplifiers in each cabinet speaker, combining hi-fi clarity with typical PA system projection. The only thing that’s often subject to change are the cartridges, depending on the night and the selector behind the decks. “Without trying to sound like a nob-head, I guess it’s important to tweak or try new things to change the sound ever so slightly,” JAZU co-founder Jimmy Hanmer explains, “the end goal being for everyone in the room to have the same sort of listening experience, no matter where you’re sitting.”

Classic Album Sundays founder Colleen ‘Cosmo’ Murphy is on a family visit in the US, in between weekend gigs, when DJ Mag calls her up. The DJ and music producer has been working in radio for over 40 years, studied sound and radio at NYU Film School and is often cited as David Mancuso’s most trusted protégé. She was introduced to kissa culture on a work trip to Japan, but it was during her early visits to The Loft, relaunched by Mancuso in the '90s, that she caught the audiophile bug. “The sound was so much more warm, enveloping and immersive, much more evocative,” she says. “I got a better understanding of how important the sonics were, even if people didn’t consciously realise that on the dancefloor.”

She also noted how effortless it was to pull a 12-hour shift on the dancefloor compared to regular club venues. “People don’t realise that when you’re exposed to prolonged loud volumes, like over 100dB, or prolonged distortion, it can really affect you mentally and really aggravate you and you don’t even know why.” Research backs this claim up. A recent study by the World Health Organisation showed that prolonged exposure to noise can disturb sleep, increase stress levels, the likelihood of cardiovascular disease and even cognitive impairment in children. “I recognised that when I left [The Loft] my ears weren’t ringing — there was no distortion so I felt like I could dance for 12 hours, which is how long his parties sometimes went on for.”

But as the decades progressed, Murphy looked on as the gradual degradation of sound production, from shoddy vinyl pressings to early music download sites, upended the music industry — the contrast with visual media couldn’t be more clear. “If you think about visuals — film, video — it got more and more higher resolution. With the introduction of the CD in the ’80s, sound was degraded, from a great high-end vinyl listening experience,” she explains. “And then it got to the late ’90s with Napster and people listening to mp3s as their ultimate listening experience. Anything to do with visuals — video, film or photography — was getting higher resolutions, sound was getting less and less.”

She started Classic Album Sundays in response, a monthly record club with a few rules: no phones, no talking, just listening. The first public event was held above a friend’s pub in north London on Murphy’s own sound system, replete with Klipschorns and Koetsus. “Hearing isn’t like seeing — with seeing we have to actually focus, turn our head to look at something, we have to adjust our gaze. We can close our eyes if we don’t want to see it. We can’t close our ears, and our ears are 360. We hear the same way we breathe, we don’t even know we’re doing it, but when you close your eyes and you’re just focusing on sound you will hear things you haven’t heard before, and then on a high-end sound system you’ll hear more details of the recording.”

Turning a passive sense into something more conscious and free of distractions proved a big hit: by the fourth instalment, David Bowie’s ‘The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust’, the BBC had arrived to cover Classic Album Sundays. “I didn’t know what it was going to develop into, I just knew it had to be done,” she replies when we ask about its enduring success. “There’s something so special about sitting in a room and listening to an album with a bunch of people. If you’re a true music-lover, once you hear music on a system in which you can have a more immersive, emotive and detailed listening experience, it's kind of hard to go back.” Murphy held events across Europe, in the UK and Australia and found a home for the club at Brilliant Corners, arguably the UK’s first bar directly inspired by kissas. Two of her two Klipschorns remained in the venue on loan for the best part of a decade.

“Anyone that’s trying to make a better audio experience, on whatever level, should be applauded. Any progress is good progress” – Colleen ‘Cosmo’ Murphy

Though focused listening events might not seem as unusual as when she first started out, Murphy’s yet to come across dedicated listening bars outside Japan that meet kissa standards. What she does note is the widening appeal of quality programming and high-end systems. “I think people are getting more demanding in what they want. They’re getting more precious on where they spend their money,” she says, adding: “Anyone that’s trying to make a better audio experience, on whatever level, should be applauded. Any progress is good progress.”

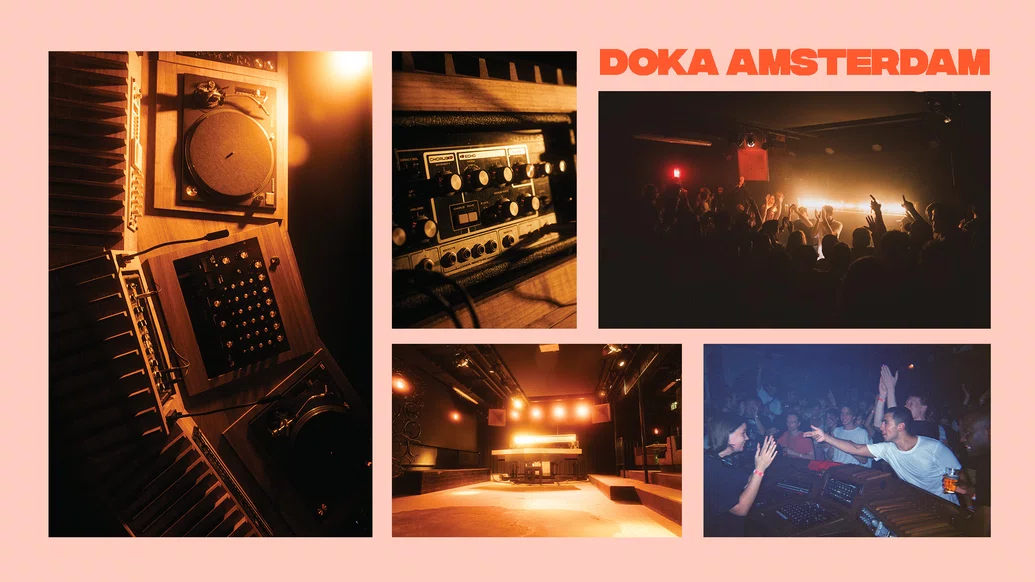

Doka, a sound bar launched five years ago, has garnered a name for itself in Amsterdam’s audiophile scene. It sits in the basement of Volkshotel, in the city’s east district, and attracts custom from the local digging community. “We’re obviously not the first to care about quality or sound systems,” says Axel van der Lugt, “but we are the first to take the concept of a listening bar and alter it to our environment.”

As cultural programmer for Volkshotel, Lugt helped transform the 250-capacity space, which began life as a “small, gritty club” before undergoing a number of other permutations, finally emerging in 2019 in its current configuration. The Doka team had to consider not only the needs of the city but the structural limitations of the building too, such as the concrete pillars that run through the hotel, carrying sound with them. “In the basement, when you make a lot of noise, the sound goes up through the hotel and if it’s too loud then the whole hotel would be awake till six in the morning,” Lugt explains, “so we needed to find something that, both technically and concept-wise, fit these conditions.”

They limited the volume to 98dBs, placed acoustic panels throughout the space and configured a six-point speaker system, adding two extra tops to carry across the room. “Now everywhere you go, you’re in the middle of the sound, so it matters less that it’s not that loud.” They also actively targeted the city’s thriving digger community, programming around “people that appreciate the room and appreciate the things that we put a lot of energy and time into.” Five years in and the Doka approach is gaining traction in the capital — more hi-fi bars have opened in its wake. But Lugt doesn’t lay personal claim to the space’s success. “The original idea came from Kamma & Masalo,” he says. “They’ve been to a lot of places in Japan and were really enthusiastic about the idea of a deep listening space that would fit the city.”

Most will know Kamma & Masalo as the DJ duo behind Amsterdam’s Brighter Days party series, but they’re also part of a crew of some 400 artists with studios housed in the back-wing of Volkshotel. Along with Julien Chaptal, they oversaw Doka’s acoustic treatment, fitting of the sound system and design of the space, from DJ booth to lighting. Although directly inspired by the Japanese listening bars they’ve visited, there’s a little discomfort with Doka being referred to as one — they gently correct DJ Mag whenever we do. “What some of the Japanese listening bars are doing is another level in presenting hi-fidelity and that’s certainly an inspiration for the space,” Masalo tells DJ Mag. “We know very well where we come from, but I wouldn’t call this hi-fi in the classic sense.”

“They put so much effort into every element, the whole chain,” Kamma adds. “I really appreciate that, but here in Europe, it might be less in our culture to have that kind of attention span — listening to a record from beginning to end, just sitting and listening. That can be quite challenging.” For them, Doka has become an extended studio space serving a wider community, with live concerts, regular club nights and other cultural events for the city. This desire for quality listening experiences is something they’ve noted over the past years, but say this can be felt more widely across clubland. “Clubs are really investing in good sound systems,” Masalo declares. “I think that's the bigger trend.”

“Clubs are realising they have to up their game in terms of sound,” agrees Justin Greenslade. “I’m getting mainstream clubs coming to me asking for stuff, and maybe a few years ago they wouldn’t have.” An engineer by trade, Greenslade set up Isonoe, a bespoke electronics company, in 2004 in anticipation of the time when venues would get more serious about sound. In the time since he’s built much of Brilliant Corners’ front-end system, including the venue’s preamp, mixer and isolator, designed Spiritland’s brass mixer, and several custom mixers for Public Records in New York.

“When I speak to various bars when they approach me, I say ‘Who’s your acoustician?’” What’s an acoustician? “Acousticians are the overlords of the audio world,” he replies, deadpan. “They will typically come in, do a few tests and tell you about your room — and the most important thing, where to put your speakers. There’s no point in us talking if you don’t get the acoustics sorted.”

“Clubs are realising they have to up their game in terms of sound... I’m getting mainstream clubs coming to me asking for stuff, and maybe a few years ago they wouldn’t have” – Justin Greenslade, engineer and Isonoe founder

The cultural landscape has moved as Greenslade predicted, with demand for bespoke products and expertise growing. The contrast with now and when he first started is striking. “Your average club 20 years ago sounded like shit — there were some great clubs around but as a rule, most clubs were just effing awful. I can think of clubs where they’ve changed the sound system and the place now stays busier later. It’s easier to socialise if you have a cleaner, less reverberant and more inviting sound, people are going to stick around.”

As vinyl sales continue to rise (the Office for National Statistics has returned the product to its inflation basket), high-end sound systems become more affordable and punters seek out gentle on the ear, luxury-leaning experiences, what at the moment appears to be an upward trend could become a staple offering — though a listening bar in the kissa tradition, where owners strive for sonic perfection, play with handmade moving coils, and customers listen to records in silence, beginning to end, seems unlikely.

What this might encourage, however, is a higher bar when it comes to programming. As Murphy advises, when playing music without mixing, “you need to not only select songs that keep you involved, that are well-crafted enough that you want to go on the whole journey, but [music] where the sonics work on a system that doesn’t lie”. In other words, poorly produced tracks won’t do. Which could, in turn, raise standards for vinyl pressings along the production chain, revealing the depths of songs we thought we already knew.