In search of sunrise: a history of Balearic trance

Ibiza played a central role in spreading a new take on trance around the turn of the millennium — a more soothing vein of the sound that captures the mood of a Mediterranean sunset. As clubs in Ibiza are opening again for the first time since 2019 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, DJ Mag dives into the roots of a genre that was inspired and shaped by the island’s unique appeal: Balearic trance

Long before turning into a global clubbing destination, Ibiza appealed to crowds looking for spiritual growth — with those from the hippie movement settling in Ibiza since the ’60s and existing through to the present day.

One of these free spirits was José Padilla, who sadly passed away in 2020. The Barcelona-born DJ is widely credited with introducing and popularising the island’s Balearic sound since the mid-1980s. Before taking up a residency at Ibiza’s much-loved Café Del Mar in 1991, Padilla sold bootleg mixtapes of his DJ sets to make ends meet. These tapes featured an eclectic range of styles, and their popularity grew over time.

“Back then, it was still very normal to play all styles of music,” recall German chillout artists Piet Blank and René Runge — aka Blank & Jones — who first visited the island in the late '80s. “You could hear acts as diverse as Soul II Soul, Timmy Thomas, The Cure and Front 242 being played by a single act, and on a single night. This eclectic range of music was the real secret of the Balearic beat movement.”

Not long after Padilla’s residency at Café Del Mar started, the club — which has been a central point of San Antonio’s sunset strip since 1980 — pushed Padilla’s interpretation of chillout beyond the venue through a series of mix CDs. The first episode came out via British label React in 1994, and the format became an outstanding success. It also placed Café Del Mar, and the more mellow sounds of Ibiza, on a global platform.

The years following saw the Café Del Mar series become one of the most recognised compilation series in electronic music, and Balearic trance eventually become a central point of club culture — both in Ibiza and the UK. The sound would also dominate numerous singles charts across Europe by the end of the '90s, before its dominance faded soon after the turn of the millennium. Yet, the sounds that represented the mood of the more relaxed corners of Ibiza maintained a loyal following — and continue to soundtrack countless chillout and beach bars across the world.

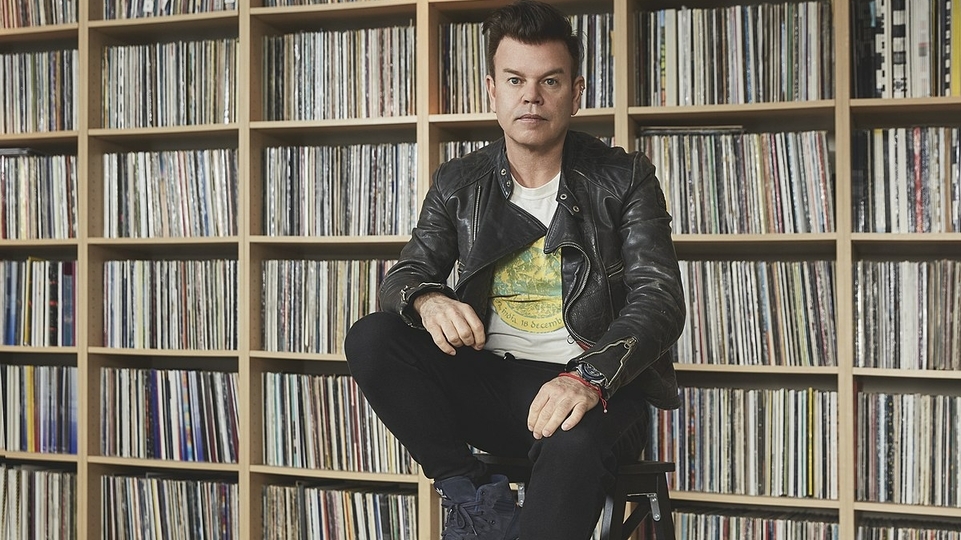

“Balearic really came to stand for all the varieties of music being played in Ibiza" — Paul Oakenfold

“Balearic really came to stand for all the varieties of music being played in Ibiza,” Paul Oakenfold, one of trance’s founding fathers, tells DJ Mag. Oakenfold visited the island during the late '80s, which motivated him to bring the electronic sounds he heard there back to London.

Meanwhile in Germany, the first strains of trance came out of Berlin and Frankfurt. Fuelled by a burst of energy and excitement following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, trance offered a welcome alternative to the then-popular acid and techno sounds. In its earlier stages, trance-inducing music attempted to emulate trance-like states themselves, translating the associated feelings of euphoria to listeners.

Growing up in Germany, Blank and Jones vividly remember this era. “It was a fantastic time. Electronic music was new and exciting. And our generation was able to create things from scratch, as there was no formal structure,” they tell DJ Mag over email. “DJs bought computers to create music to play in their sets, while official clubs were built out of illegal warehouse parties.”

Around the same time, acid house had taken hold of the UK. Although considered an underground movement, the acid house reign did turn the British clubbing scene into a commercially viable and scalable operation. By the mid-'90s, state-of-the-art superclubs such as Cream (opened in Liverpool in 1992) and Ministry Of Sound (based in London since 1991), as well as nights like Gatecrasher (founded in 1993 in Birmingham and later moving to Sheffield), catered to thousands of clubbers every weekend, each playing a part in the increasingly nuanced sounds of trance.

One of these trends became known as progressive, or prog. British DJs playing the sound, such as Dave Seaman, John Digweed and Nick Warren, started to incorporate genres such as breakbeat, house and techno in their sets. They specialised in building long, winding narratives with deep and emotive music. Paul Oakenfold was amongst those DJs who picked up on the genre. “Towards the end of the '90s, trance was turning more fast and anthem-like,” he remembers. “The progressive movement offered a slower, deeper alternative.”

The progressive movement coincided with the rise of a more soothing vein of trance that was able to capture the mood of a soft, Mediterranean sunset perfectly, and would eventually become known as Balearic trance. The sound had grown out of the Balearic beat movement and incorporated sonic tropes of the trance sound popularised in Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium and the UK. Balearic trance generally featured a mix of string instruments, like Spanish guitars and mandolins, combined with sounds commonly associated with Mediterranean seascapes, including the ocean and birds.

Laying further emphasis on the atmospherics through the layering of stretched-out, spacious pads, Balearic trance also bears a close resemblance to, and borrowed elements from, earlier ambient movements. Compared to the powerful trance sounds that started to reach mass appeal, Balearic trance offered a mellow and soothing alternative.

Having been a central point of the music played by residents at Café Del Mar for some years, by 1997 the first pieces of Balearic trance found their way out to the wider public — and quickly struck a chord with clubbers. German artist Torsten Stenzel, for example, sold over 250,000 copies of his single ‘The Awakening’, which came out under his York alias, reaching No.11 in the UK charts. The track features an instantly recognisable guitar melody, which was played by his brother.

“It was a fun time, because we finally had all these possibilities to incorporate real instruments in electronic music — which was really new to everyone,” Stenzel tells DJ Mag. “So we played around with saxophones and guitars — everything was possible. We had a lot of freedom.”

“That inability to be pinned down to any particular genre in many ways defines the Balearic sound. It’s an atmosphere” — Ben Lost

The success of Balearic trance quickly brought a surge of what are now widely considered to be classics over the next two years, peaking in 1999, dubbed ‘the year of trance’. Another standout from this time was ‘Seven Cities’ by British producer Richard Mowatt, aka Solarstone, which features a blend of dreamy melodies, Spanish guitar licks and exotic-sounding samples. Although appreciating the popular appeal, Mowatt considers the success of ‘Seven Cities’ to be taken out of context. “I believe it was a good record, yet it was also just another release for me,” he explains. “Its status has been assumed by those who heard it at a particular time in their lives: the Ibiza connection, the general explosion of trance. It was a matter of it being the right moment for that track.”

Released in the same year was ‘Greece 2000’, by Dutch duo Three Drives. Having been produced in just a few days, the track’s undeniably summery sound found its way into the top end of the UK singles chart. “The trance scene was growing rapidly and events were evolving to a higher level all over Europe,” says Erik de Koning, one half of the duo, reflecting on that era. “‘Greece 2000’ fitted perfectly at that moment. It just seemed to mix the right sounds and melodies.”

The global success of these tracks was caught in the increasingly upward spiral enjoyed by more commercial trance music globally. As the sound became more prominent in Ibiza, superclubs across the island hosted huge trance nights, while tracks featuring Mediterranean instruments and recognisable melodic hooks — think ‘Dimension’ by Salt Tank, ‘Beachball’ by Nalin & Kane and ’Summersault’ by TasteXperience — continued to garner mainstream interest. It wasn’t long until an array of labels capitalised on the music’s then-nascent appeal.

Around this point there was a divide between the Balearic beat sound — pushed in Ibiza by DJs including José Padilla and Jon Sa Trinxa, and immortalised on releases from the Café Del Mar label, which was formed in 1999 — and the Balearic trance which translated to wider international recognition at the time. British platforms such as Manifesto, Lost Language and Xtravaganza tapped into the latter, with releases that generally began to clock in at a higher BPM. These imprints boosted the popularity of British producers such as Agnelli & Nelson, Chicane and Salt Tank.

Ben Lost ran the Lost Language imprint at the time, which turned into one of the most vital subsidiaries of British powerhouse Hooj Choons. “I loved that cinematic late ’90s trance sound, and there was loads of amazing stuff coming out — especially in Europe and the United Kingdom,” he says. “Back then, we’d licence underground trance from labels such as Black Hole and Lightning, and then commissioned our own remixes. Also, we were lucky enough to get first refusal on any new material from Hooj artists such as Lustral, Tilt and Solarstone.”

And it wasn’t just the sounds of Ibiza that became a part of trance. The rich natural aesthetic of the island turned into trance’s iconographical patchwork. Elements of the island became an important part of track titles and record designs. Key examples can be found in the work of Tiësto, who ventured on a new path for trance with his ‘In Search Of Sunrise’ mix compilation series in 1999. Inspired by his extensive travels as an in-demand trance DJ, the Dutch icon emphasised more house-infused elements such as vocals and acoustic instruments on these compilations — which he curated and mixed until 2008.

“The ‘In Search Of Sunrise’ series was one of the flagships for the trance scene,” reflects Three Drives’ Erik de Koning. “Tiësto certainly contributed to the promotion of this Balearic trance sound, yet I think it would also have turned big without his efforts. Those summer-induced vibes just felt right for a lot of people.”

While trance reached a commercial breakthrough across Europe, ambient trance gained increasing popularity as a welcome counter-movement around the turn of the century. Releases labelled ambient trance often included slow-paced, silk-smooth remixes of four-to-the-floor trance productions, making them perfectly suitable for chillout rooms and bars.

The works of British producer Michael Woods and his home label Lost Language played a major role in strengthening the ambient elements in trance. Woods’ pitched-down reworks of tracks such as ‘Café Del Mar’ by Energy 52, ‘Eugina’ by Salt Tank, and ‘Peace’ by Saints & Sinners crafted a fresh take on trance in an anthem-focused era.

“We happily commissioned ambient, house and breaks remixes. That was something we were always open to,” says Ben Lost. “Michael Woods was already on the scene when I joined Hooj in 1999. He’s an incredibly versatile producer, and alongside his club productions, he had been making expansive, ambient trance music which we later released on Lost Language under his Accadia alias.”

Lost Language’s move towards ambient-inspired trance didn’t steer the genre as a whole in this direction. On the contrary, the popularised sound of trance became faster and increasingly uninspired. It took until the mid-'00s for the trance boom to burst and the sound to implode, providing space for a wider sound spectrum.

A prime example is the career arc of Blank & Jones. After having success in trance during the late '90s, the German duo directed their efforts to craft easy-listening chillout music. “Our trance track ‘Cream’ became quite a hit in the summer of 1999, and resulted in us being booked on Ibiza for years to come,” say the duo. “When we were there, we always tried to extend our stay to chill at hotel pools and bars like Café Del Mar and Café Mambo, where they played these fluffy downbeat tracks. We loved it and wanted to recreate these sounds that fitted the amazing sunsets we witnessed there.”

The duo’s ‘Relax’ series, established in 2003 and reaching its 13th instalment in 2021, ranges from ambient to jazz, and has been a big success. Their mixes pull heavily from the sound José Padilla envisioned back in the '70s and '80s.

Robert Miles — best known for his dreamy trance hit ‘Children’ from 1995 — also helped continue the Balearic legacy by setting up online radio station OpenLab on the island in 2013, creating a musical base on the island to showcase alternative, mellow music ranging from ambient and chillout to modern classical and jazz. Although the platform faced closure after Miles’ death in 2017, OpenLab was revived in 2019. Its programming is certainly not limited to purely Balearic sounds, but it remains a thread that runs through its musical output to this day.

Over the last three decades, Ibiza has crafted its own lane musically. Yet, the distinctive sound of the island is not limited to a single genre. Instead, it encompasses and opens up for many interpretations. “That inability to be pinned down to any particular genre in many ways defines the Balearic sound,” says Ben Lost. “It’s an atmosphere.”