Beginner's Guide: Compression

In the latest edition of our new series exploring the basics of music production, E.M.M.A. explains how to use compression to beef up your drums, make a vocal performance feel more controlled, and 'glue' your overall mix together

I didn’t give compression much thought in my early days of producing. ‘Do You Even Compress, Bro?’ was met with ‘What’s It Got To Do Wi’You, Pal?’ It would have been beneficial to get my head around it early on, so it didn’t end up being this big thing. The sooner you understand the basics, the more easily you can figure out how and if you can apply it.

Compression processes the dynamics of a sound by reducing its dynamic range: the distance between its loudest and quietest level. It can be applied to individual stems and/or the whole mix.

“You can help a vocal performance feel smoother and more controlled, you can make hi-hats feel like they're swinging just a bit more and drums feel punchier. You can make a whole track feel 'glued' together,” explains producer, composer and Ableton tutor for Hub 16, Mwen.

The goal when applying compression to a sound is usually to make your mix more cohesive. It can also add fullness to a kick or snare for example. However, if you randomly slap it on without knowing why, it can destroy your dynamics.

Now here’s the science part

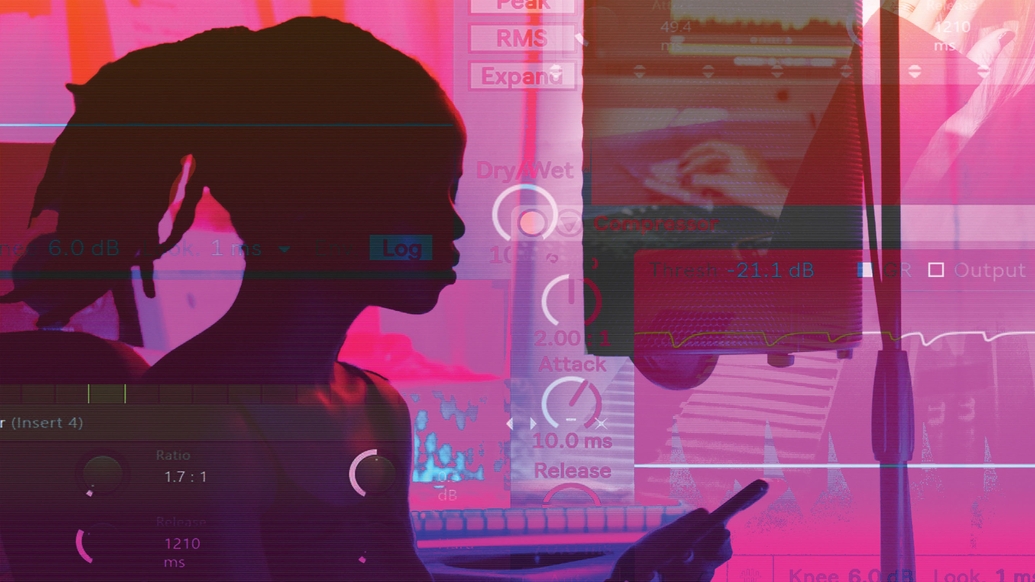

So what do the knobs on your compression plugin actually do? While there are different types of compressors there are some commonalities: key ones being threshold, ratio, attack, release and makeup gain.

The threshold sets the dB level at which the compressor activates. Anything above that level is made less loud. The ratio determines by how much. For example, a ratio set to 3:1 targets volume that exceeds your threshold by 3dB, and reduces it to 1dB above the threshold. The higher the ratio, the stronger the compression.

Attack is the time it takes for the audio signal to become fully compressed, and release is the time it takes to go back to its original uncompressed state.

You’d apply makeup gain to increase the volume at the output of your compressor, as the overall volume decreases during this process.

One thing to keep in mind is sometimes compressors such as Ableton’s built-in one have ‘auto makeup gain’ switched on by default. This will automatically make what you’re doing sound louder, which we’ve come to think sounds ‘better’ but as we know this isn’t always the case. Therefore as you are making threshold adjustments, be sure to click the auto makeup gain on and off to make sure you are happy with the changes.

Similarly, some instances of FL Studio open a blank project file with a limiter on the master channel. When I first got my tunes mastered in 2012, I didn’t even notice I’d left it on the pre-masters, but mastering didn’t raise any red flags so I seem to have gotten away with it.

Get creative and experiment

It’s difficult to know what to listen out for in the beginning. “Using it on your own recordings is a great start – you hear the difference right away” suggests producer pal Murlo. “I have a lot of fun recording ambient sounds on a microphone then compressing it so brings out all the details.”

Daddy Kev, LA-based audio engineer, producer, DJ, founder of Low End Theory and owner of Alpha Pup Records is currently writing a book on compression, Audio Dynamics. I’m lucky enough to have read a lil’ snippet, and it is an immersive and accessible read; a real opportunity to learn from the best – so keep an eye out for that.

I caught up with Kev for a deep dive into compression and was inspired by the way he talks about it, which I have not heard from anyone before. Kev weaves art, science and philosophy together to convey how it can be applied to production; like a painter choosing different brushes for their characteristics.

Some of this chat is a little more intermediate than beginner, but bookmark this article for future reference.

Emma: Kev, as a professional mix engineer, what are one or two typical reasons why you might use compression?

Kev: “Vocal mixing almost always involves some sort of compression. If you conceptualise the human voice as simply another instrument sound, on a relative scale it varies greatly in dynamic range accompanied by a myriad of transient shapes and frequencies depending on the vocalists and recording conditions. This is where having some sort of overall compression can be critical for intelligibility. Also important for vocal mixing is the use of a frequency-specific downward compressor targeting 4000Hz to reduce sibilance (i.e. the sizzling "ess" sound) on vocals—also known as a de-esser.”

Emma: Do you have a go-to favourite compressor technique?

Kev: “I love parallel compression, which is compressing a sound and then mixing it back with the original. Allows you to keep the original dynamics in place, and effectively ‘dial-in’ the compression. Plug-in compressors with mix blend parameters do the same thing.”

Emma: What can compression add to a mix creatively?

Kev: “Changing the input of your sidechain can provide some great creative results. Also, changing to a higher ratio can effectively flatten a stereo image as well as the dynamic range. In sound design, this can be useful, e.g., for making drum sounds.”

Emma: As we know, a beginner won't necessarily know what to listen out for in order to apply a compressor correctly. For anyone curious to apply it to their creations, what is the simplest way to try it out in their project file?

Kev: “Try it on your stereo mix to begin with. I'd recommend initial parameters of low ratio – 2:1 or 4:1 – with the slowest attack possible, and medium-to-fast release. From there, dial the threshold until you start to see the gain reduction kick in. Compare how 1-2dB of gain reduction sounds versus say 3-4dB, then 5-10dB. Insofar as which is best, there is no wrong answer here – go with your ears and your emotion. For stereo mixes, my sweet spot is 1-3dB of gain reduction at the loudest part of the song with a 4:1 ratio, 30ms attack, auto release on my SSL G-comp.”

Mastering: The final compression

Compression is used to add ‘excitement’ during the mastering process, explains mastering engineer Katie Tavini. “It can really change the mood! However, it's really easy to over-compress a master, so always keep referring back to the un-processed track to make sure that you're adding goodness rather than killing the vibe.”

As always, keep it simple. “Ask yourself before you use it, ‘Why am I using this? What do I want it to do?’” says Mwen. “Sometimes less is more,” concludes Kev. “One sound that almost never needs compression: 808 bass drum.”

![Screenshot of [untitled] app interface](/sites/default/files/styles/djm_23_961x540_jpg/public/2023-09/untitled-app-music-new-1400x700.jpg?itok=wdcYnfKW)