Bradley Zero: State of rhythm

Bradley Zero has built the reputation of his Rhythm Section label and parties by nurturing quality music rather than chasing trends. On a roll, his latest venture is a residency at London’s XOYO club. We catch up with him to talk community, gentrification, colonialism in music, and his label’s purpose...

“I’m just pulling onto Rye Lane,” says Bradley Zero, as he drives from his flat in Peckham to his office and studio.

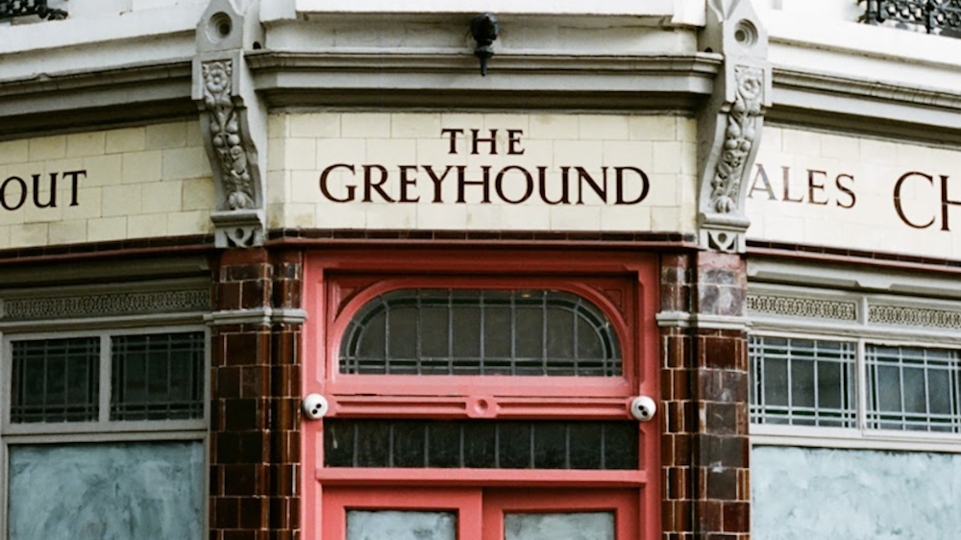

It’s usually a bustling and vibrant high street, a rat-run of entrances and exits, fried chicken takeouts, delivery vans parking on double yellow lines, Halal butchers, cyclists weaving in and out of traffic and multi-cultural markets spilling out onto the pavement. But today, it’s “grey and miserable and feels a little quiet”, not least because rolling sections of the street will be closed until 2020 for major gas works.

This populous and popular area of south-east London has been Bradley’s neighbourhood for 10 years. In that time, he’s established his Rhythm Section empire with what he strictly calls “dances”— rather than events or parties — at Canavan’s pool club. It’s also here that the lively Rye Wax has popped up with a record shop, DJs and a relaxed bar and cafe all serving the artistic community.

But, as is the way with similar enclaves everywhere from Brooklyn to Berlin, the people who breathe new life into formerly neglected communities are the first to have to leave when rents begin to rise. “You would not believe how much money places in Peckham are rented for,” says Bradley, who moved to London from his native Leeds in 2006 to study at the Slade School Of Fine Art at UCL. “Not luxury flats with penthouse views, high-end fittings and under-floor heating. People are literally renting a mouldy bedsit for £1,600 a month.”

“For me, Rhythm Section is about small venues outside the centre, doing things a little differently, so XOYO is a departure from the core foundational principles of the dance, but it’s not a strict end. That’s why I was careful not to make it a Rhythm Section residency”

COMMUNITY

When he first arrived, he lived in Peckham and Camden, but felt there was no real community, which is something clearly very dear to him in the way he runs his party and label. Alas, he says he is now starting to feel the losses in Peckham, with friends moving and places shutting down. “It still has its heart,” he says. “It is still the same place, but the change is palpable, and it’s hard to see where it goes next. In maybe 15 years I can’t see there would be a place for Rhythm Section.”

Importantly, he recognises his own role in all this. “Let’s be real, I enabled a whole generational exodus to Peckham,” he says. “I put on a party and it got popular, so it’s easy for me to complain, but the people who are the agents of change are the first victims. Art school kids in search of cheap rent can no longer afford it, they are the ones who move further and further out, and as this path of gentrification deepens, the things that cause it in the first place suffer.”

With that in mind, Bradley allows himself “a sense of achievement” for having set up the South East London Housemate Co-op. It’s a Facebook group that connects people looking for rooms in the area, and cuts out the middle man. It has more than 45,000 members, and he hopes to somehow mobilise them all with some direct action, protests and pleas for some form of rent control, “to counteract the greed of estate agents”.

The first shift in Peckham came when Canavan’s pool club changed the way it operated, and Bradley ended his long-running dances there. It was a small place down a grotty little alleyway, with a bunch of pool tables used by locals and students. But on its small dancefloor and behind soundproofed walls, magic happened every fortnight for a number of years.

An absolute anthesis to many high-end and identikit clubbing experiences in the capital, the focus was on the music and community rather than the guests or anything else. It was an unwritten rule, but photography was banned, and dancing was essential. Set times were never published. It was all very impromptu and instinctive and, before long and with minimal promo, it was full each and every time. Guests like Andrew Ashong, Andy Blake and FunkinEven did play, but were decidedly choice, low-key names rather than guaranteed ticket-sellers.

“There was no pressure to book a name to bring people in,” says Bradley on his hands-free phone. “People came whoever was on. We just made a vibe. It could be Pender Street Steppers one week, and me and my housemate Miles another week, but you always got the same crowd.”

The dancefloor was always as mixed as any you might find on the London circuit. “It’s arbitrary to try and encourage that diversity,” he says. “You can’t create it. It happens from the way you do things, the way you engage.” Rather than shouting about it, he believes the best way to address the issue is with direct action. “The imbalance won’t be fixed overnight. The root cause goes deep, and that’s why we set up the Rhythm Section studio — to get people in who haven’t got the chance to jam, or can’t afford the set-up.”

DEPARTURE

Over the last year or so, Rhythm Section has rolled up to a range of homely venues from Five Miles to Copeland Gallery, Corsica Studios to The Jazz Cafe and Rye Wax. Since Friday 5th April, though, Rhythm Section dances have been on pause, as Bradley has stepped up to a 12-week residency at XOYO. It marks another chapter in his story, that has slowly but surely developed from his first residency in a local bar to the first parties at the pool hall, via early squat raves in The Bussey Building, to a busy international tour diary. But he is adamant that this bigger platform changes nothing in terms of Rhythm Section.

“For me, Rhythm Section is about small venues outside the centre, doing things a little differently,” he says, “so XOYO is a departure from the core foundational principles of the dance, but it’s not a strict end. That’s why I was careful not to make it a Rhythm Section residency. It’s just me, but me getting to do things I couldn’t otherwise do in a small pool hall.”

“Finding new ways to transcend borders and cultures is what drives the discovery, not just doing the same thing over and over again”

Of course, Bradley is all about new music – on his label, in his DJ sets (most of the time) and on his radio shows on NTS and the In New Music We Trust residency on the BBC. But the XOYO gigs have seen him play differently to normal, while giving a bigger platform to many of the fledgling artists he is so invested in.

“There are two versions of me,” he says. “The Rhythm Section resident, playing what I want in a small venue to a home crowd, where I feel so free I can literally play anything and it’s liberating and really comfortable. But on the other side, that almost got too easy. It wasn’t really a challenge to think about what I had to play, ‘cause I had total freedom. XOYO will be another side of me, the ‘on tour me’, playing to different crowds who won’t necessarily get how I play at home, so this is an exercise to play in London in a way that I haven’t had much opportunity to before, which is quite exciting.”

Musically, ‘Rhythm Section Bradley’ takes in disco, jazz, soul, funk, dub and R&B with a smattering of more club-ready sounds, while ‘on tour Bradley’ is slightly more dancefloor orientated, featuring house and techno of the sort that he releases on Rhythm Section sub-label International Black. Either way, though, new music is always a main priority. For that reason, he explains that his Radio 1 shows were “a real challenge” to cram in so much new music, and “represent who you want to represent” in such a short space of time, and still make the hour flow. Rather than going after established producers with Rhythm Section International, which he feels “other labels do well”, Bradley says, “finding new ways to transcend borders and cultures is what drives the discovery, not just doing the same thing over and over again”.

To date, that MO has led to deep house, broken beat and jazz-funk discoveries such as Chaos In The CBD, Al Dobson Jr and Henry Wu aka Kamaal Williams, all of whom are now relatively well-known after putting out what went on to be breakout records on Rhythm Section. “Rhythm Section doesn’t have a sound but a purpose, and that is to discover and nurture new talent,” says Bradley, whose latest projects have seen him work with London garage man MC Pinty, Australian soul collective 30/70 and French jazz, hip-hop and house producer Neue Grafik.

“We get so caught up in old music, but to me it’s more to do with claiming stuff, proving you got there first or that you are more deeply connected to this, or that your digging skills are better than anyone else’s. It also often has a weird colonial thing to it — no one is reissuing European folk music, it’s always South African or West African or Indonesian music, and it’s mainly done by white men. It’s weird, people are reissuing archival things. Just play it on the radio. Put it on your Spotify playlist. Just share it. It’s this strange sense of ownership over things that have already been released that I don’t understand.”

MAGIC HAPPENS

On a constant mission to share, Bradley has, “without ever planning it” and over a long period ended up at the centre of a multi-faceted empire that takes in A&R, DJing and broadcasting. He is not some overnight success story who broke through off the back of a big production or two. The obvious but watertight comparison is with Gilles Peterson, someone he looks up to and still gets shivers when remembering the time Peterson played a Rhythm Section track (from Al Dobson Jr’s 2014 album ‘Rye Lane Volume One’) on the radio for the first time. He feels that having so many different things on the go actually relieves the pressure. “If one record isn’t a massive hit, it doesn’t diminish the overall story. Plus the radio gives me a lot of structure, picking things out for that, gauging the reactions, then packing a record bag off the back of it.”

Despite being a vinyl lover, more and more these days, poor set-ups around the world mean he often plays off USBs. “DJing is a spiritual thing, it’s about being connected with yourself,” he says. “When you’re in a flow state, it’s almost just happening. It’s not easy to get there, you have to work at it and nurture it, but when you get in a transcendental state is when the magic happens.”

Despite graduating from art school, that chapter of Bradley’s life is over. He paints, to his chagrin, only occasionally, but feels the way things are taught and the way that art is approached and discussed “strips it of all majesty and meaning. It’s demystifying”. He agrees that may be why he has never got into production: knowing the ins and outs might somehow lessen the enjoyment.

“The best art, film or painting, you don’t feel the need to have it explained. It is a connection that hits you really hard, and that is enough, you can’t really put it into words. But when you take art in an academic institution, suddenly everything has to be justified and examined, every brushstroke or word has to be a reference to a philosopher or critical theorist, and it just drains it. What I found with music is that it is always so immediate and beautiful that you don’t need to explain it. You feel it or you don’t. If it’s good, people will like it. If it’s not, they won’t.”

After a long and bureaucratic process a while ago, Bradley’s passport states his citizenship as Dominican, which comes from his father. He’s proud of his roots, and put out a charity compilation to help the island after Hurricane Maria devastated it in 2017. He also has thick, heavy dreadlocks going half the way down his back. They haven’t been cut since his mum shaved his head as a teenager and he vowed never again, but his relationship with her remains strong. She was the first person he called when he got asked to host early Boiler Room shows, and when he got the news of his BBC Radio 1 residency. “You can say you’re playing Berghain and they really wouldn’t understand, but even my gran listened to my first Radio 1 show.” He takes on a Caribbean accent to repeat her review. “Oh yes, I enjoyed it, but I didn’t make it all the way through.”

It was Bradley’s father — a jobbing DJ and record store owner — who gave him his first introduction to music by letting him play records at DJ gigs while he nipped to the toilet. His mum, meanwhile, worked a job in First Direct to send him to a selective private school in Wakefield. “She was probably concerned how I might turn out if I went to the local state school. If you look at the stats of young Caribbean boys, the outlook isn’t good.” Bradley was “the only brown person” in his year at school and also lived in a place in Leeds where he never saw anyone remotely like him or his sister. “That was just normal, that was just life, I didn’t feel like an outsider because I lived on the outside my whole life.”

It was moving to London for art school that suddenly opened his eyes. “It wasn’t like I saw this beacon and thought, ‘I must move there, these are my people, this is my place,’ but when I arrived it was just a whole level of community that was open to me that I didn’t know existed. If you’re in school from the age of seven, you don’t realise how much you are indoctrinated. We were walking round with plaques on our blazers with a Latin motto, ‘it is a disgrace to be ignorant’, whilst also being very sheltered from the real world.”

His escape during school years was music: The Prodigy’s ‘Experience’ off his dad, and minimal by Richie Hawtin and Heartthrob from a school friend. He would go to the parochial clubs in town mainly to dance, but never really connected with the commercial R&B, pop and metal music that was played. “I hadn’t really joined the dots between this underground world of music, that I appreciated but didn’t know how it worked or where it happened,” he tells DJ Mag.

He had always gone to Leeds’ famous Carnival with his family, so soon got wind of the notorious Sub Dub at the West Indian Centre, and credits going there as his real introducing to proper music. Around the same time, even before he was old enough, he got a job in a bar, and aged 16 he went to the notoriously intense Mint Club on New Year’s Eve 2004 and wondered, “what the hell was going on”.

Now sat in his parked car outside the busy Rhythm Section office, he’s 200 miles from home, but right where he feels he most belongs.