At home with: Amp Fiddler

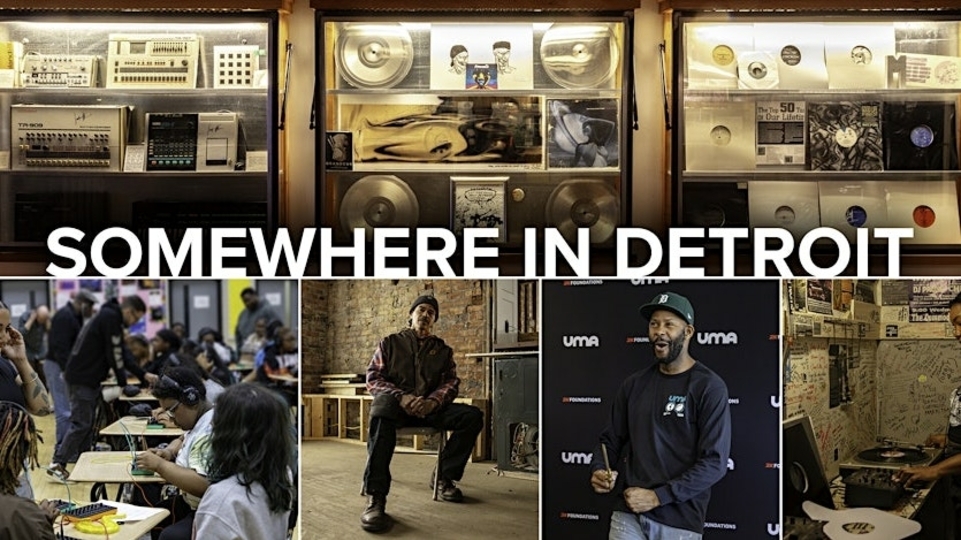

Tajh Morris spends an afternoon at the home and studio of legendary Detroit musician and educator Amp Fiddler, who talks about his hybrid live show and the magic of collaborating with fellow Detroit artists

Conant Gardens, on the eastside of Detroit, Michigan, is a microcosm of the city as a whole. Once a neighbourhood with a thriving Black middle class, it fell on hard times, as most American inner cities did, in the post-civil rights era. A potent mix of white flight, trickle-down economics and gang-related drug violence wrecked this once prosperous enclave. In the face of this, though, some extraordinary musical talents have come from Conant Gardens: Omar S, Waajeed, Dez Andres, J Dilla and Slum Village, and of course, Amp Fiddler.

Joseph ‘Amp’ Fiddler is a rare talent, someone who’s been involved in decades of evolving musical styles. When he was 19, he and his brothers moved into Amp’s long-time Conant Gardens home, where they played music together. Amp focused on piano, while Thomas ‘Bubz’ Fiddler took up bass guitar. (Bubz remained a creative partner and confidant to Amp until his death in 2016.)

Amp’s musical career began when he was at university in the ’70s, with Detroit soul group Enchantment. Eventually, his talent led him to become a keyboardist in one of the most influential American bands of the 20th century, George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic. His relationship with Clinton allowed him to access the music industry, hone his skills on tour and create demand for himself as a session musician. After a stint in Los Angeles with the remnants of the P-Funk empire, Amp returned to Detroit in the late ’80s, where he’s lived ever since.

The first thing you see when you walk into Amp Fiddler’s home is a grand piano in the living room. It’s next to a small setup: a few pieces of electronic gear, the newest additions to his sprawling collection. Since so many pieces have come through here, Amp likes to keep his newer pieces upstairs until he gets comfortable with them. When they feel more familiar, he moves them into his basement studio space.

Amp leads us into the basement, where there are two separate setups, a vocal booth, drum kit, couch, and a shelf filled with a few hundred records with a TV on top. In the far corner, there’s his computer surrounded by keyboards. Next to the couch lies the current iteration of his live show, which he explains is sometimes (perhaps awkwardly) billed as a DJ set. In the last few years, all of his performances have been a combination of DJing and live musicianship. These hybrid sets have had different configurations, but essentially consist of a keyboard, MPC, standalone DJ controller and a microphone.

For his current live show, he’s using a Roland Jupiter-Xm, Denon DJ Prime Go, Akai Force and a TC-Helicon Perform-VE for vocal processing. He’s fond of the Roland MPC series — it’s easy to riff on, a quick route to his one-man band operation — and his two Traynor K1 Keyboard Combo amps, which he uses as monitors, and often feature in his local gigs.

As he runs us through this, what stands out most is that, for someone of his pedigree, it’s shockingly easy to talk with Amp Fiddler. Bluntly, artists who have accomplished a fraction of his accolades can sometimes be pompous, as if their time is inherently worth more. Amp’s down-to- earth attitude is a breath of fresh air in a culture drenched in ego.

Amp has been focusing on this “one-man band” format, playing mostly solo tours or collaborative performances in the last decade. This happened as a natural progression rather than because of any one, significant event. “A lot of times, I had a band that I loved and we were all tight,” he says, “but it was just hard because you have hotels, per diems, travel costs, musician fees... man, I was just coming home with a few bucks,” he laughs. “I had gotten some gigs where they introduced me as a solo artist, because I didn’t have a band at the time. I thought it would be cool that, when I didn’t have a band, I could work as a DJ so to speak.”

After establishing a relationship with Native Instruments by making two production sample packs (titled ‘Amplified Funk’ and ‘Conant Gardens’ respectively), Amp was given a Traktor setup sometime between 2010 and 2012. His first DJ gig was for a friend’s wedding. There was an admitted learning curve which drew some ire from his DJ peers, for moving into their world before his skills were polished. He remembers early moments when his transitions were off, or when he would let songs play out so that the audience would applaud. Some DJs would be quick to tell him that what he was doing was wrong, but their criticisms didn’t matter much. “For the most part, people were happy and having fun, that’s what was important to me,” he says. In DJing and in live performance, Amp focuses on the audience being satisfied, and everything else is chalked up to a learning process; trying new things out and making use of errors.

The COVID-19 pandemic has dealt live entertainment a devastating hand. While many have turned to playing on live streams and meeting Bandcamp Friday deadlines, Amp has kept busy in his basement. This has been the de-facto space for most of his creative process, recording with local artists and finalising music for release.

“I really don’t go outside the box too much because I’ve been down here too long, getting better at it,” he says. “Getting the sound I want.” We’re treated to a taste of his current live show. He plays a few tracks off the Denon, jamming some loose riffs and basslines. The funk is strong down here. This basement studio is where he’s recorded much of his discography, and where he’s tutored young artists, too.

Amp is a teacher and collaborator, a trait he shares with Mike Banks of Underground Resistance, a fellow Detroit mainstay. When Amp lived in California he started Camp Amp, the unofficial production school that moved back to Detroit with him in around ’88-’89. Amp and Bubz used an advance from Polygram Records to build their home studio, buy an MPC and reel-to-reel tape, and “as much [else] as I could squeeze out of 10 grand,” he laughs. This build would become instrumental in the development of hip-hop in Detroit.

Teaching became a labour of love for the brothers, inviting local kids, quite literally off the street, to use their studio. During a turbulent time for Black youth, this was a place for the kids to focus their energies and become familiar with the rudimentary aspects of music production. Many of these students went on to be integral figures in Detroit’s hip-hop community: T3, Waajeed, Dez Andres, Proof (of rap group D12) and, of course, J Dilla. This period is often mentioned in Amp’s story, but the importance of these Camp Amp lessons on the larger hip-hop mythos cannot be overstated — he taught these teenagers the necessity of a sampler in the changing hip-hop landscape.

“We get magic when we work with other people, other musicians, as opposed to cats who sit around and do everything by themselves”

Dilla and others had access to Amp’s vinyl record collection, a large portion of which he inherited from his elder sister and brother. This included tonnes of jazz and rock, which educated them beyond the funk and soul heritage of Detroit Black music, and became material to learn sampling, drum programming and basic recording techniques. Sadly, most of these records were lost in a basement flood some years ago. Dez Andres took a large number of the salvageable ones, the majority were disposed of, and a small grip remains in Amp’s basement.

As techno was coming to fruition, Amp was only vaguely aware of it. When he wasn’t in the studio he was on tour with Clinton, so his exposure to the new electronic club music of Detroit was limited to occasional downtown parties and local radio shows in the late ’80s and early ’90s, especially the Electrifying Mojo. But techno was such a core development in post-disco Detroit that it was impossible to not come across it as a music lover.

Bubz and Amp had been doing session work in the late ’90s and early ’00s with saxophonist Norma Jean Bell for an artist they knew only as Kenny Dixon Jr. Amp was then-signed to UK label Genuine, whose management often spoke to him about a Detroit artist named Moodymann. It was not until Dixon Jr. brought records featuring the brothers’ session work to his home that Amp connected the dots: “If you’re hearing techno, then you’re hearing synthesizers,” he says, “so if you love synthesizers, you have to love techno.”

But it wasn’t until much later that Amp really dove into techno — albeit through an unexpected route. In 2010, he played in Lagos, Nigeria, for the annual Felabration — a week-long festival celebrating the life and work of Fela Kuti — alongside fellow Detroit artist Theo Parrish and pioneering Afrobeat drummer Tony Allen. Amp recalls Parrish pushing himself to rise to the occasion of playing live music with traditional musicians. This moment was a major catalyst in Parrish’s desire to form a band. In 2015, Amp performed background vocals and keys for The Unit, Parrish’s group of Sound Signature associates and dancers.

“The Unit was put together by Theo when he decided that, like some [other] DJs, they want to do something different,” Amp remembers. They embarked on the Teddy’s Get Down Tour; interpreting Sound Signature productions — like Parrish’s 1996 track ‘Walkin Thru The Sky’, and tracks from his 2014 album, ‘American Intelligence’ — and covers of favourites of Parrish’s DJ sets, like Skye’s 1976 ‘Ain’t No Need’.

After touring with The Unit, Amp performed one of his earliest hybrid DJ-live shows at Amsterdam’s Dekmantel festival in 2016, right before Moodymann’s set. It was at this gig that another Detroiter, DJ Bone, introduced him to his current agents, who helped Amp put together ‘Amp Fiddler & A Drummer From Detroit’, a series of live collaborative performances with Dez Andres on percussion. In a full circle moment, the teacher and former Camp Amp student became peers, releasing music together on Moodymann’s Mahogani Music as well as being frequent collaborators on other projects.

Amp has bought and sold numerous pieces of equipment over the years, but is currently refocusing on analogue gear: always with a preference for keyboards and, of course, synthesizers. He first purchased a Moog Prodigy on layaway in the ’70s, and his collection’s grown ever since. When asked what his favourite pieces of equipment are right now, he mentions three keyboards: the Sequential OB-6, Sequential Pro 3 and Roland System-8.

Current samplers include the Akai MPC X and Maschine, which he used to produce the expansions for Native Instruments. He claims to have owned at least 10 different MPCs throughout his career, starting with the MPC60. An Arturia MicroFreak Hybrid Synthesizer, Pioneer DJ Toraiz As-1 Monophonic Analog Synthesizer and a gorgeous VOX Continental Synthesizer Organ are all plugged in and ready to go.

Armed with this collection, Amp has been guiding others again. He’s working with a local MC called X (Xavier) that he met at Dillatroit, a Detroit chapter of the celebration of J Dilla that happens every February. In another full circle moment, it’s touching to see the man who mentored J Dilla now mentor a young artist inspired by J Dilla.

Then there’s the playfully named The Dames Brown, a female trio with an old school soul vibe, who met working on one of Amp’s more electronic-leaning albums, 2016’s ‘Motor City Booty’. They’re currently putting the finishing touches on their debut album for Defected Records. The production work is sleek and powerful, with elements of gospel and Motown, and some of the tracks have the potential to be summer clubland anthems.

There are a number of other projects in the pipeline. Amp is launching Ampliphonic, a new record label for his own material. The first release is slated to be a reissue of his 1989 debut, ‘With Respect’: a concept album, co-produced with Bubz, that fuses funk, New Jack Swing and ’40s jazz. Starting out as a demo on Polygram and ending up on Elektra, the album was not well received by label executives at the time. After hearing a few of the songs from ‘With Respect’ now, it’s a shame, but not surprising, that the suits didn’t understand it.

Also lined up for Ampliphonic are a series of older records: a number of tapes of Amp and Bubz’s music, originally cut to four-track, have been rediscovered, some of which are being restored and mastered for release. There’s an album’s worth of sessions with the late Tony Allen and Chris Bruce, a longtime friend and Parliament-Funkadelic guitarist. Amp plays a few, spectacular tracks from this, all loaded with Afrobeat rhythms and pulsing funk melodies. And for long-time fans, another treat — the long-awaited Digitarians project will soon be available, an Afro-futuristic project with guests, including George Clinton.

Most tantalising, though, is the re-release of his very first record, ‘Sundown’ (or ‘Space Cadets’, as one pressing of the record shows) — ‘Spaced Outta Place’, on Sound Signature. This is a rare seven- inch record that not even Amp owns a copy of anymore. It’s been unavailable for purchase for a long time, and older copies have sold for high prices online. Amp’s also recorded a modern version of it with The Dames Brown, laying down fresh vocals that will feature on the re-release.

Although the future seems uncertain, Amp Fiddler isn’t scared of the unknown. His scrupulous work ethic has guided him through achievements and struggles, and kept him humble and excited about each new project. His patient craftsmanship has allowed not just his own career to grow, but the careers of many fellow Detroiters, too. “We get magic when we work with other people, other musicians, as opposed to cats who sit around and do everything by themselves,” he says candidly.

In a time when people are disconnected and feeling afraid, the work of an artist like Amp Fiddler feels all the more special, working with others to highlight human connections, and let the talents of others shine.