How dance producers are using video game livestream platform Twitch to connect with fans

Video game live streaming platform Twitch has become an increasingly valuable way for electronic musicians to connect with their fans. Cherie Hu investigates the synergy between these electronic worlds

As the global live streaming market for games generates an estimated $5bn a year, several tech corporations are fi ghting to claim their share of the sector,including but not limited to YouTube Gaming, Facebook Gaming and Microsoft’s platform Mixer. But by far the biggest market leader is still its earliest mover, Twitch, which was founded back in 2011 and ranks ahead of its corporate competitors by a long shot in both viewership and content creation.

According to a report from Streamlabs and Newzoo, the number of hours that channel owners broadcasted live on Twitch in the fourth quarter of 2019 was more than the number of hours people watched any content at all on its next biggest rival, Mixer, over the same time period (82.7 million versus 82.5 million, respectively).

As Twitch continues to expand and infiltrate mainstream culture, it’s also becoming more interested in breaking through its own stereotype as a gaming-only platform. “We’ve seen non-gaming content on Twitch quadruple over the last three years, and we’re continuing to invest in new ways to grow and support this content,” Athena Koumis, a Music Partnerships Manager at Twitch who was hired in January 2020, tells DJ Mag. And that kind of content is getting more engagement from viewers, too.

According to a report from StreamElements, Twitch viewers watched 81 million hours of videos tagged “Just Chatting” in December 2019 — which is exactly what it sounds like: streamers “just chatting” with viewers, and/or engaging in a variety of non-gaming activities. That’s more viewership than the League Of Legends or Fortnite categories got on Twitch over the same period. And fortunately for the DJ community, the history of music on Twitch — and of gaming music in general — is inseparable from the electronic world.

Many of the core characteristics underlying electronic music — percussive rhythms, repetitive hooks, vocal-free instrumentals and high-tech gear setups — make the genre particularly conducive to collaborations with gamers and game developers, and Twitch has frequently served as ground zero for these collaborations in the modern era.

The first major concert ever broadcast live on Twitch was Aoki’s Playhouse at Pacha Ibiza in August 2014, a showcase featuring the titular Steve Aoki alongside Bingo Players, R3HAB and other DJs. Yet while Aoki continued to invest more in e-sports and gaming audiences — eg. performing at TwitchCon and investing in e-sports team Rogue in 2016 — the DJ actually has not live streamed much at all on Twitch since his ground-breaking Ibiza show.

In fact, the only material on his Twitch channel today is a 37-second Thank-you video filmed after his 2014 Ibiza set, in which the DJ calls Twitch “a dope interactive platform that I can’t wait to put more of my events on and share with you guys” — a promise that has yet to be fulfilled.

“I think people in the music industry need to look at Twitch more like a social network than like a music streaming platform” — Dan Le Sac

In subsequent interviews, Aoki admitted that he encountered some challenges in embracing streaming culture on Twitch to the fullest, given his background in live performance: as he told Dot Esports in 2017, “I need to see a physical crowd in front of me to build my energy level”.

It turns out Aoki isn’t alone in his ambivalence around the platform. Given the fact that Twitch is owned by corporate giant Amazon — and has historically hosted some of the world’s highest-earning gaming influencers earning millions of dollars each — you would think that penchant for corporate mega-stardom would translate to Twitch’s music partnerships.

In fact, corporate interest is coming from the outside: two major labels now have their own electronic and hip-hop-focused e-sports subsidiaries (Enter Records at Universal Music Group and Lost Rings at Sony Music Entertainment), while one of the world’s largest artist management companies, Red Light Management, launched its gaming and e-sports vertical Hit Command in January 2020.

Yet virtually no major label electronic artist is active on Twitch on a regular basis today. Hardwell, Afrojack and Martin Garrix haven’t streamed for the past three, four and five years, respectively Zedd, Skrillex, The Chainsmokers and Tiësto each have verified Twitch accounts, but have yet to go live on the platform at all. (Illenium, who regularly streams himself playing first person shooter game Escape From Tarkov for three to five hours at a time, is a rare exception to this trend.)

By and large, the most active and vibrant communities around electronic music on Twitch today centre on independent artists like JVNA, HANA, Flux Pavilion, Dan Le Sac and Grimes, as well as indie labels like Monstercat and Anjunabeats.

This is a stark contrast to mass-market music streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music, which seem to give the majority of attention and real estate to major labels and already-established acts. Many of these independent artists go live on Twitch once or even multiple times a week and do... well, whatever they want.

Like many others, they sometimes stream themselves playing video games — but more often than not, they bring fans behind-the-scenes in their music production and recording processes, preview their own unreleased music in exclusive DJ sets, give viewers backstage tours before their shows, or even just hang out in their bedrooms and answer fans’ questions about their careers and lives.

In the process, they’re breaking new ground and introducing audiences to new paradigms of creativity, fan engagement and monetisation that, if they gain more traction, may rewrite the rules of Celebrity and career success in the music industry altogether.

As a traditional artist or record label, it’s tempting to treat Twitch the same way you’d treat any other video platform like Snapchat or TikTok — namely, as a music discovery tool, in which you can seed your music to key influencers (ie. gamers) who would play your tracks in the background of their streams and subsequently attract the attention of their loyal audiences.

But to pull this off as a platform, you need to acquire the proper rights — and from a licensing perspective, Twitch’s relationship with the electronic music industry has been opaque at best.

Back in 2015, Twitch launched an extensive music library featuring hundreds of royalty-free tracks from well-known electronic labels like Spinnin’ Records, Dim Mak and OWSLA, that streamers could include in their videos without fear of getting flagged for copyright infringement.

The live streaming company also formerly maintained an extensive Spotify profile of playlists with pre-cleared tracks for streamers. It seemed like a much smoother and friendlier process compared to the constant DMCA-related takedowns that gamers were facing on YouTube and other on-demand video platforms.

But the original URL for the music library (music.twitch.tv) now redirects to the main Twitch site, and Twitch’s Spotify profile has been completely wiped. The company’s official music guidelines now seem stricter as well — explicitly laying out that streamers are only allowed to play music in the background that they own, or that they licensed directly from rights holders, with no mention of the Twitch Music Library as an alternative resource.

DJ sets, cover song and karaoke performances, “radio-style music listening shows” and even displays of third-party lyrics or musical notation are technically not allowed on Twitch if any third-party material is included without permission. Detection of such elements (Twitch has a partnership with content identification start-up Audible Magic to do the job) will cause a video either to be muted or to be taken down altogether once its live stream is over.

From an electronic artist’s perspective, this means that traditional community and brand-building vehicles — eg. the hour-long mixes that are commonplace on Mixcloud and SoundCloud, or the live video streams of DJ sets on YouTube like those from Boiler Room — face fundamental barriers to growth on Twitch to copyright claims.

Some third parties have built alternative music resources from which gamers can draw without getting a copyright notice, such as Monstercat Gold and Pretzel Rocks, both of which cost $5/month and pay artists the majority of that price tag. But the most exciting activities that electronic artists are promoting on Twitch have nothing to do with licensing, or even with traditional concerts or performances they feel much more social rather than commercial, without any direct line to revenue.

“I think people in the music industry need to look at Twitch more like a social network than like a music streaming platform,” artist Dan Le Sac tells DJ Mag. “If you look at a social platform like Twitter, most of the time you’re not really selling anything. You’re expressing your personality and building connections with people first, and then they go, ‘Oh, I actually like him, I’ll go check out his music’. You shouldn’t immediately be thinking, ‘How do we make the most money out of this?’”

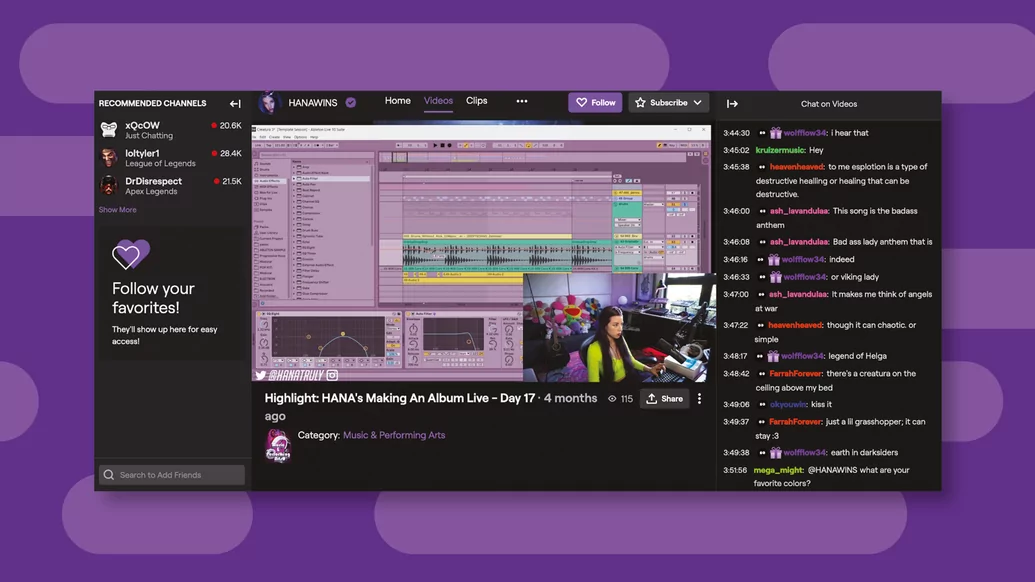

Many artists bring fans into their creative worlds on Twitch with an unprecedented amount of transparency and even companionship. For instance, artist HANA live streamed the entire recording process behind her latest album ‘HANADRIEL’ on Twitch over the course of four weeks, from start to finish.

For each of 20 total live streaming sessions, she filmed herself for eight to 12 hours in a row writing, producing and recording songs from scratch in her home studio, while answering questions and incorporating feedback and suggestions from fans throughout the process.

“My subscription numbers almost doubled while I live streamed my album, and people were donating a lot as well. It’s one of those things that rewards you the more you do it” — HANA

HANA has also live streamed her tour rehearsals, post-show reflections and, yes, video-game sessions — both solo and with fellow artists such as Rina Sawayama. It’s become her one-stop shop for hanging out with fans in a more longform, direct and unfiltered manner from what other incumbent social platforms like Instagram might allow.

Similarly, fellow electronic artist JVNA frequently holds open-ended Q&As with fans on her Twitch channel, alongside live music production sessions and live DJ sets of her own music that often last two to three hours each. Grimes has hosted multiple live Twitch Q&As — most recently in honour of her latest album release, ‘Miss Anthropocene’ — and has also brought fellow artists HANA and Megan James (Purity Ring) on board as live stream guests.

These kinds of drawn out sessions can seem excessive and unpolished at best, and boring at worst. But to veterans of live streaming culture, that’s precisely the point. “As a music producer, if you want to release highly crafted content about how you make your sound, YouTube would be a better place to do that, because you then have the liberty to edit your videos and create a distinct narrative,” says Dan Le Sac.

“Whereas Twitch is more like, ‘Come hang out with me in the studio as I play around with this snare drum for an entire hour, and I’ll answer any questions you may have’. It’s like having the company of a few people around your house to share in the experience of what you’re doing. I think people make a really big deal out of live streaming, but if you think of it just as hanging out with some like-minded people, you’ll have a lot more fun.”

Comfort with being transparent and vulnerable emotionally is also an imperative, especially if you’re streaming and chatting with fans for hours on end. That said, there may be some workarounds. “It is inherently vulnerable because people are seeing you all the time, but I think there are ways you can play around with it and make it a little more mysterious, whether by using green-screen erects or just putting in pause screens,” HANA tells me. “That’s what's so exciting about the platform to me, that it’s so customisable.”

While Twitch works best as an organic, non-commercial social channel, its business models are also innovative from a musician’s perspective. Fans can subscribe directly to an artist’s Twitch channel for a monthly fee, and/or donate Twitch’s native currency “Bits” directly to artists during their live streams. “My subscription numbers almost doubled while I live streamed my album, and people were donating a lot as well,” says HANA. “It’s one of those things that rewards you the more you do it.”

There do remain some limitations to independent artists’ growth on Twitch. One such obstacle is discoverability. If you scroll down the “Electronic Music” or “DJ” tags on Twitch on any given day, you’ll find mostly unknown DJs in Europe and Asia performing in their bedroom for 10 to 20 concurrent viewers.

This isn’t inherently bad — but there’s no clean way to filter videos by musical genre (ie. there are no separate tags for “funk” or “tech-house”), nor is there any way to search archived videos (ie. only live broadcasts show up in search results — so if you wanted to find HANA’s album streams, for instance, you would have to go directly to her channel page). The result is multiple, unrelated niches jumbled into one interface, creating a confusing and frictional experience for the end user.

Another related challenge is that viewership on Twitch and other live streaming platforms skews even more heavily towards the top blockbuster accounts than towards the long tail. One academic study from 2015 found that 70 per cent of views on Twitch came from just 0.5 per cent of broadcasters — an even worse skew than the real-life concert sector, in which the top 1 per cent of performers claim 60 per cent of touring revenue.

That said, indie artists do have an inherent advantage over major stars in navigating Twitch as smoothly as possible. Indie artists tend to own most or all of the rights to their work, significantly whittling down the bureaucratic list of rights holders from whom they would need approval to start a stream.

Electronic artists in particular are accustomed to consistency — releasing singles at regular intervals to keep their audiences interested — which is especially important for follower retention on Twitch. And indie artists in general are more used to cultivating intimate relationships with their fans.

In addition, just like in the real world, one of the most effective means for indie artists to grow their audiences on Twitch is by building relationships and cross-pollinating audiences with other artists, the way that HANA did with Rina Sawayama and Grimes. “Full-time streamers who are streaming six to eight hours a day are probably going to sit on Twitch for another two to three hours just talking to other streamers in their chats,” says Dan Le Sac.

Dan also suggests that indie labels could learn from indie game developers, many of whom have community managers who stream weekly on Twitch and talk with fans about the games they make. “A label like Warp Records could have someone in their office stream on Twitch once a week and talk about upcoming releases, anniversaries and other milestones, to show their audience what their company is really all about,” he says.

By driving much of the growth of music as a category on Twitch, indie electronic musicians are turning the nature of celebrity and artistry on its head. Instead of cultivating a well-polished brand based on some form of mystique, Twitch native DJs are imbuing their creative processes with full transparency from the beginning, and are fostering real-time relationships with fans based on raw and unfiltered rather than overly calculated personalities.

“There’s a balance I want to maintain in terms of keeping parts of the music as a surprise to fans, but at the same it was such a rewarding, positive and inspiring experience,” says HANA of her inaugural album live stream. “Even if it’s just once every year or two years, I definitely want to do something like this again.”