Moving mountains: How a community of electronic artists are capturing the imagination of Kathmandu

Having experienced natural disasters and political uncertainties, a group of young Nepalese artists and organisers are looking to re-create an electronic music scene of their own

Nepal has always captivated imaginations. Nestled in-between two superpowers in India and China, and settled atop the Himalayas, the highest mountain range in the world, the country has more than 2,000 years of history and culture. Nepal has also become a destination for those seeking a unique cultural experience. As such, the capital city of Kathmandu, the all-access point for the country, boasts a remarkable musical landscape: a vibrant incubator of not just DJs and producers, but a welcoming group of people, eager to form a community.

“I’ve seen lots of interest from India and Pakistan here, probably because we’re a peaceful country,” Nepalese producer phatcowlee says over the phone. With tensions growing in other parts of South Asia, especially between Pakistan and India, Nepal has become a hub for artists to congregate. “I can invite a Pakistani [and] an Indian here and they can all perform,” says Rishi Jha, the co-founder of cultural agency We All Should Play. “If an Indian wants to go to Pakistan, it’s impossible. If a Pakistani wants to go to India, it’s impossible. Here, we celebrate being South Asian.”

“The more recent version [of the scene] starts at the advent of the millennium,” says Ranzen Jha, the unofficial godfather of the Nepali electronic music scene. “Weekly Tuesday rituals at Club Galaxy [where] DJs like Ankytrixx, Kranti, and Nishan featured, were the early dances in Kathmandu. Later, Funky Buddha started as a go-to venue for psytrance music.”

Soon, the scene sprouted offshoots. Party Nepal, an events company, provided the first website for upcoming event listings. Electronic music arrived on TV and, led by some music outlets in Kathmandu, primarily in the tourist area Thamel, a new kind of lifestyle evolved. Younger generations started gravitating towards house, techno, and bass-heavy music, and a distinct DIY culture developed: festivals such as Shanti Jantra, Universal Religion, Moodelila, Dark Sun, Ambient Valley, and Dancemandu were all held between 2007 and 2014.

“Slowly, there has been a rise in the club scene as well as the independent electronic music [scene],” says Rohit Shakya, a singer-songwriter and producer from Kathmandu. “We haven’t had any artists that have made it into the mainstream here in Nepal just by doing electronic music, so it’s more of an underground thing.”

DISASTER

When the electronic music community in Kathmandu appeared to be taking some sort of shape, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck, killing nearly 9,000 people and injuring nearly 22,000. It rendered hundreds of thousands of Nepalese homeless, affecting entire districts, and destroying more than 600,000 structures. The damage to the country was an estimated $10bn.

“Everyone was prepared for a festival called Mountain Madness when the earthquake hit,” Ranzen recalls. “[The festival] was a yearly thing that used to happen. Since then, this festival is no more.” With frequent aftershocks for two or three months, no one seemed to be working. People were staying in tents, afraid of what was to come. Brothers Ranzen and Rishi slept outside in a garden alongside dozens of others. There wasn’t a scarcity for food or drinks, but life was at a standstill.

Hundreds of thousands of Nepalese were living in tents in Kathmandu and in the surrounding regions, too. Villages had been flattened, and the collective mindset was of a heightened sense of despair. Centuries-old buildings had been destroyed. Despite these conditions, the people wanted to retain a sense of normalcy. Their want to regain control of their lives was driven by a desire to simply, once again, have fun. “The first gig [after the earthquake] was next to my brother’s house,” Rishi says. “We organised a party with Ranzen, and we danced [again] after a long time.”

“It overall affected the mood in the city,” confesses Marta, the co-founder of We All Should Play. “Before the earthquake, when I went [to Kathmandu] the first time [in 2014], there was a wind of change. Everyone wanted to feel something and grow. The earthquake slowed things down very much.”

The earthquake, with a blockade of petrol trade from India to Nepal, resulted in stagnation. The city was in a period of relative quiet as it regrouped, found one another among the rubble, and started anew from the fragments that had splintered across the capital. “I think, more than anything, it brought people together,” YNZN P, one of the more in-demand and sought-after DJs and producers in Kathmandu, says. “People were stressed for months,” Ranzen elaborates. “And then they slowly started coming out. Kathmandu had only a handful of clubs that played electronic music, but it’s mushrooming now.”

GROWTH

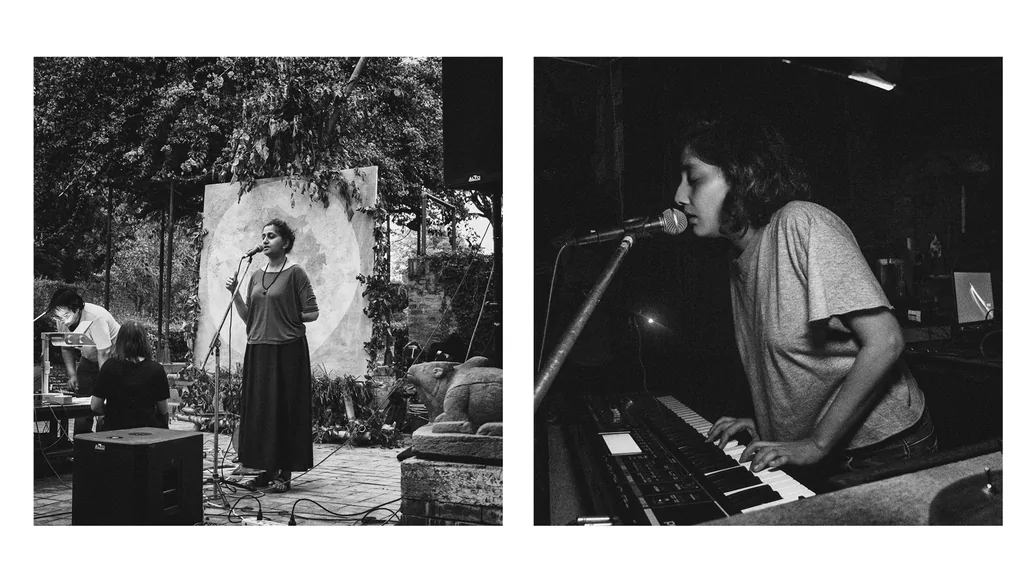

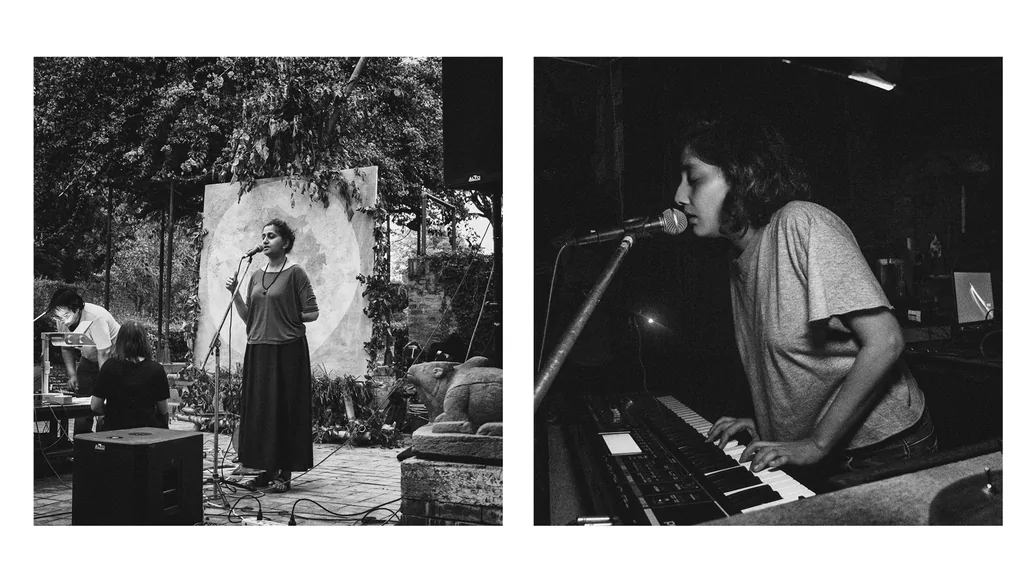

Initially, there was a dearth of clubs playing electronic music after midnight. Now, in Thamel, there are a dozen venues that do so. Marta moved to Kathmandu after the earthquake and set up Sofar Sounds, a series of intimate gigs that take place in non-traditional locations. She’s witnessed first-hand the change in the country.

“When I first got to Nepal in 2014, it was very far from what it is now. Every other month [now], there is something new happening. Someone new is starting a concert series, a podcast series. There is a young generation finding a way in the scene and changing things, speeding things up.” With an investment in small cafes, bars, and venues, Kathmandu rebuilt its scene from scratch. Having that empty palette, members of the scene took off in different directions, being given the freedom to affect the culture how they’d like.

Phatcowlee, the electronic music moniker of Rajan Shrestha, emerged from this liberation. In 2017, he released a four-track EP titled ‘Cinema’ on Indian label Consolidate. It would go on to be lauded across South Asia, looked upon as a seminal piece of work from a Nepalese producer. And Shrestha himself was surprised at the turnout of his first live gig as phatcowlee, due to the relatively uncharted territory of his music. “I had no idea I had an audience because nothing was out yet. I didn’t know what they were expecting of me,” he admits.

The relative unknown quality of Nepalese musicians is also what led to the creation of Sine Valley Music Festival. Alien Panda Jury, a Pakistani artist, flew to Nepal as part of a Coke Studio assignment in 2012, and was blown away by the talent. M.Manal, aka Autonomotor, a Maldives-based artist, felt the same way. Both of them met in Karachi in 2015, and when they met again in Berlin the following year, at a Karachi Files concert, they decided to bring the idea of a festival-cum-residency to life. “It was nice, it was fresh,” phatcowlee reveals.

Since the initial two editions, the funding for Nepali concerts and residencies has dried up. For Rishi and Marta, the husband-and-wife duo who run We All Should Play, this has proved immensely difficult in creating their residency Seashells On The Mountains. “The biggest obstacle is investing in culture,” Rishi discloses. “There is no support for the commercial side.” Right next to a country like India, where corporations like Boiler Room continue to heavily invest in the culture, Nepalese artists are frustrated for their future.

“Within Nepal, there aren’t many cities that you can tour,” YNZN P. describes. “Artists don’t go to other cities because there is no market. It boils down to the audience as well. Maybe how receptive they are.”

THE FUTURE

Despite having faced myriad obstacles to get to where they are now, the Nepalese artists look towards the future with a mixture of hopefulness and uncertainty. “It’s a growing environment, it’s changing very much,” Marta admits. “It’s not easy for Nepali artists to just apply for visas and go. So, it’s a long way to go, but in the past few years, it’s been positive.”

Rohit echoes Marta, saying, “I think the scene is very small here. It’s important for new listeners to know what’s happening here in Nepal. I think it’s important that this music should go outside of Kathmandu as well.” In a year marked by the occupation of Kashmir by India, further straining the fraught relationship with Pakistan, the importance of Kathmandu as a centre for artists has been revealed. YNZN P. has just played a Boxout In Transit show, a showcase put on by Indian online community radio station boxout.fm, where they exhibit sounds from a new city with each edition.

Thinking on the show, he says, “As a people, we are welcoming, and we’re hungry to learn and to have that interaction, and have that exchange with people from different countries. Plus, it isn’t as strict. Kathmandu has been a bit lenient, and arts have really flourished in that sense.” “Kathmandu is a hub,” Rishi Jha states. “The mingling of all this young energy, especially in electronic music, I think that’s the good point about Kathmandu.”