The word 'rave' has lost all meaning

During the early '90s the word 'rave' conjured up images of the era's legendary acid house parties. 30 years on — hijacked by the tabloid press to feed search engine optimisation and commodified by marketers who use its imagery to sell products — it's become a maligned term. So what does rave mean in 2020?

During the ‘90s, the term ‘rave’ became a buzzword in the tabloid press. And it’s happened again in 2020. So much so that they write about “illegal raves”, even if it’s just people chilling with some speakers and a few cans of beer.

To understand why, you have to look at their digital strategy; the term ‘rave’ ranks higher as a searchable keyword phrase than ‘gathering’ or ‘unlicensed event’. It will appear higher in Google’s omnipotent rankings meaning more people will read and more advertising revenue will therefore be generated.

The result? Everything becomes a ‘rave’. Let’s take the Daily Mail, for instance: In recent weeks, their editorial team have insisted on crowbarring the keyword ‘rave’ into titles about some trouble at a barbeque on a beach (which they described as a “beach cookout rave”), a BLM protest and people dancing in a kebab shop.

This orgy of search engine optimisation has morphed the meaning of the word. The phenomenon is compounded by marketers who have used the term to sell products; from t-shirts to kaleidoscopes to chewing gum and everything in between. Over the past three decades, the term ‘rave’ has been repurposed, repackaged and resold over and over. So much so, that it’s lost all meaning.

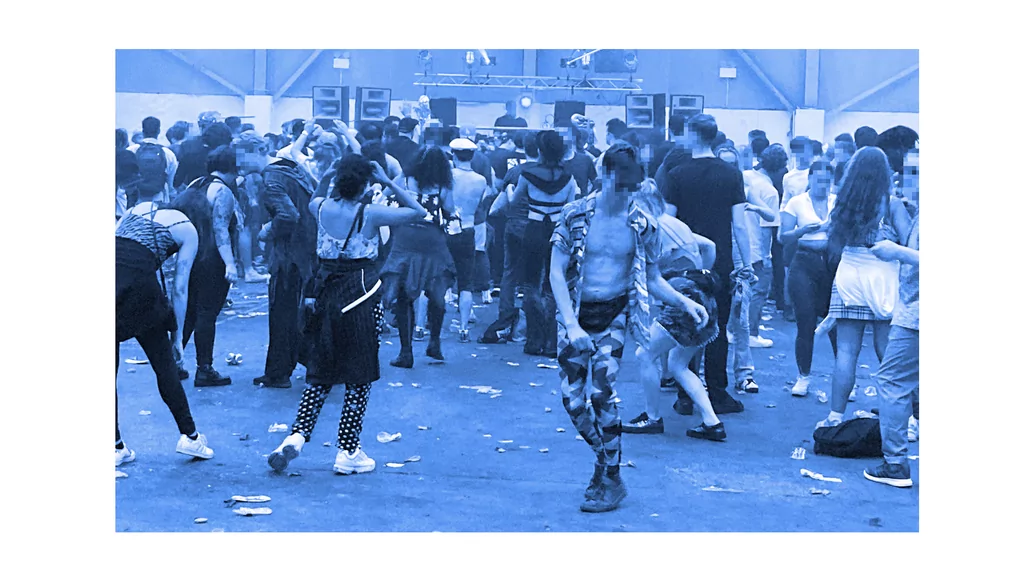

It's been widely reported that there has been a spike in unlicensed music events in the UK this summer. And, like the original parties of the acid house movement, all the basic elements — lights, repetitive beats and drugs — are still there in one way or another three decades on. But the term ‘rave’ has become more complex: What does the word ‘rave’ mean in 2020?

“The spirit of acid house (the freedom to be who you want to be without aggression) was as important as the music” — Terry Farley

I recently asked a French girl the question at a free party. She didn’t believe this was a ‘rave’ because it’s “just someone putting on a party”. She thinks a ‘rave’ must be political in some way. On the underground scene it seems dated, almost unfashionable to use that term.

Dictionary.com defines a ‘rave’ as “a boisterous party” whereas the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 (Thatcher’s legal response designed to kill the acid house subculture off) ruled that a rave was a gathering of 20 people or more which involved an “amplified emission of a succession of repetitive beats played throughout the night”.

When I spoke to people from the generation who were around when the legendary acid house raves (1988-92) took place, common themes popped up. A ‘rave’, many said, was pegged to a specific moment in time when the politics, fashion and new music collided with new drugs creating a sociological atmosphere that was ripe for a fresh subculture. It was that specific snapshot in time which connotes the word ‘rave’.

“People now talk about raving anywhere, but I think of the original ones in fields — they had to be illegal and secret otherwise it wouldn’t have been as exciting,” one woman, who was 17 in 1988, explained. Another, who nearly flunked her college exams due to the acid house movement, said: “Raving is the illegal side of things for me – off your head in a field or abandoned warehouse, at that time.”

But when I questioned a much younger cohort (aged 16 to 21), the answers are different. One told me that “you can have a rave with your nan at a wedding”, another described it as “socialising and relaxing”, and one said it “means a good night out with your mates”. To another, it means to dance in a certain way. A 19-year-old man explained that it makes him think of “the Stone Roses” whereas an 18-year-old woman quite poetically described it as “a complex feeling of collectivism”.

In June, the Greater Manchester Police released a statement reporting that they are seeing a “growing number of planned raves”. When I spoke to one of their press officers, I asked what the force officially class as a ‘rave’.

There was a silence.

“That’s a good question,” he responded. “I don’t have a definition to hand but let me get back to you.” He never did. So, I quizzed my mum, who is 60 and is staunchly anti-rave. “The vision I get of a rave is a big, out of control, outdoor party with loads of people who have had a lot of drugs,” she said.

During the early ‘90s, many ‘raves’ were similar; essentially huge outdoor, DIY festivals. Now, three decades later, it’s a colossal industry, they come in all shapes and sizes; from 40 people dancing at a Boiler Room stream to a sweaty 500-cap underground club to 10,000 people in a dance tent at a festival. ‘Raves’ have become a catch-all term for anything focused around electronic music, but now they can provide a vast range of experiences.

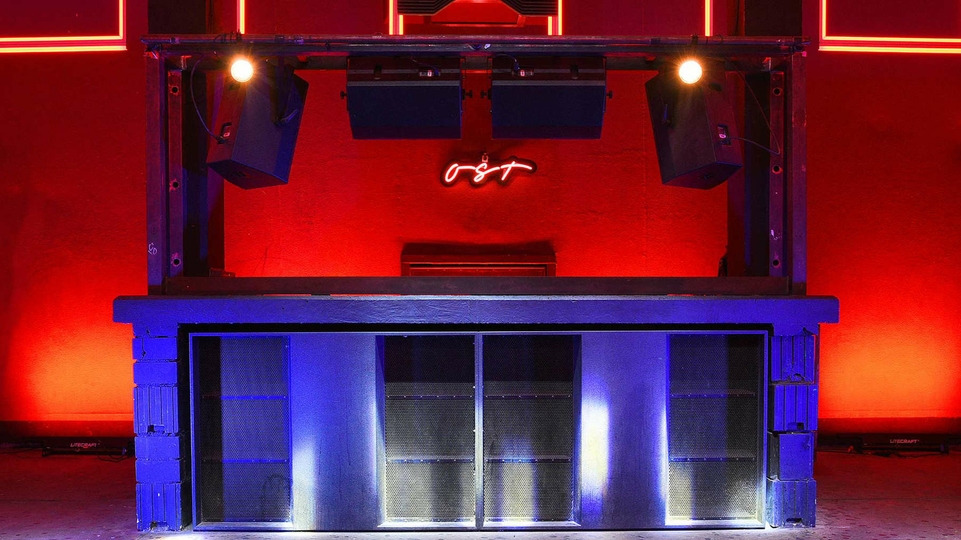

When I recently interviewed a Director at Broadwick Venues — the corporate clubbing behemoth behind London venue Printworks — he seemed to at first distance himself from the term ‘rave’, preferring to describe his offering as “electronic music events”. Later in the interview, though, he described himself as “the world’s biggest rave promoter”.

Terry Farley who (alongside the late Andrew Weatherall and others) founded the seminal Boy’s Own crew, who released records, put on parties and ran a satirical fanzine during the acid house era, explains to me what the term means to him.

“Raving was, for my generation, an old London Mod word adopted by the Black community in the early 1980s, especially those on the ‘two-step scene’. For acid house crews, ‘raves’ meant those big commercial M25 parties,” he says.

“The word seems to have been rehabilitated and appropriated by newer generations, which is a good thing,” Farley reckons. “The spirit of acid house (the freedom to be who you want to be without aggression) was as important as the music.”

So, what does ‘rave’ mean in 2020? Your guess is as good as mine.