TYGAPAW: music for the revolution

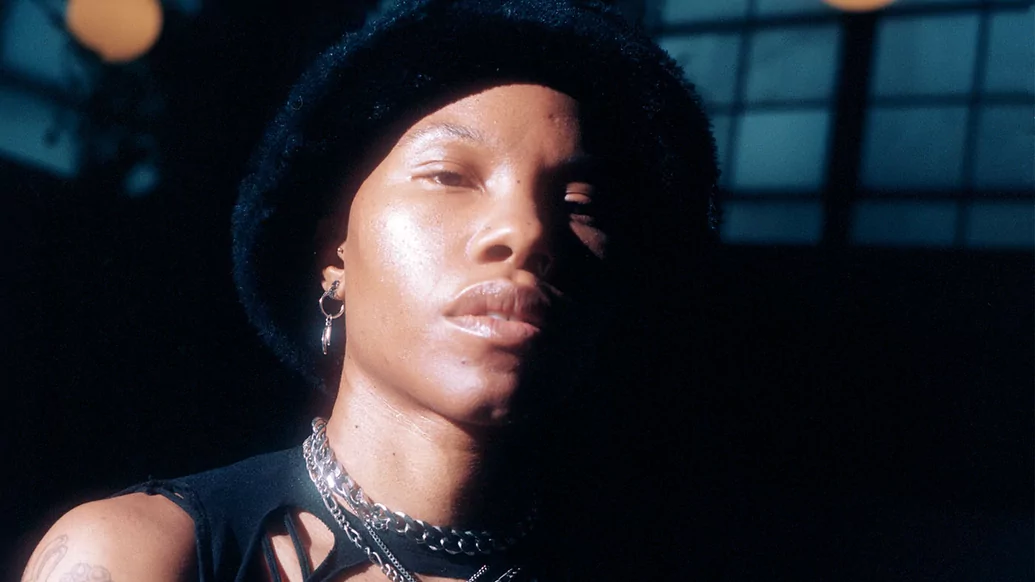

TYGAPAW makes music with a message of liberation, and of working toward a world where everyone is free to be true to themselves. It also happens to be music that slams. Bruce Tantum meets the Brooklyn-based artist to learn about their long journey to get to where they are now, and the road ahead

There’s a documentary called Underplayed, released in 2020, that focuses on gender, ethnic, and sexual equality issues within the electronic music world as seen “through the lens of the female pioneers, next-generation artists, and industry leaders”, to quote its press materials. It features footage and interviews with a wide range of figures, from synth trailblazers Delia Derbyshire and Suzanne Ciani, and ascendant figures like the Toronto DJ/producer Ciel and dance-music activist Maxie Gedge, to festival faves TOKiMONSTA, Rezz and Nervo. The film’s most moving focal point, though, belongs to the Jamaica-born, Brooklyn-based Dion McKenzie, better known as TYGAPAW.

In the segment, McKenzie considers the restraints of their conservative Mandeville upbringing (“being a black girl from an island, that patriarchy was really stifling — it was like, ‘You’re gonna be a housewife’”), their early penniless days in NYC (“I rarely had any money to take the subway, or how I would afford a meal that day”), and how they are perceived in their homeland’s culture (“As a queer black woman, I’m off their radar”), among other topics.

The poignancy is palpable, but the TYGAPAW passage ends in what feels like triumph: We see McKenzie putting together a vogue track featuring the vocals of ballroom artist Infinite Coles, and the snippet of the tune that we hear is fantastic. The segment flows like a seven-minute epic, a life story in miniature — in its massively abridged way, those few moments manage to trace a path from societal repression to joyful freedom.

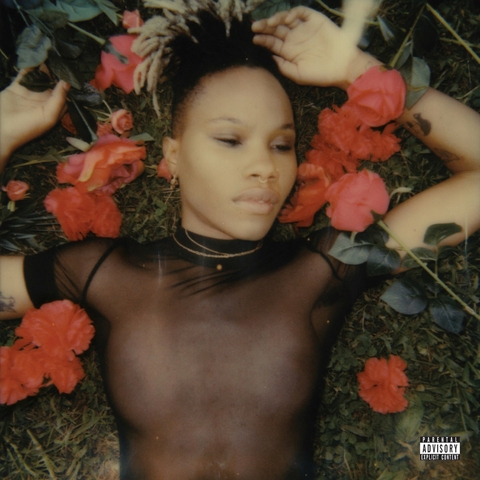

In the documentary, as well as in interviews and photo spreads, McKenzie comes across as both seriously fierce and fiercely serious. This is a perception reinforced by late 2020’s ‘Get Free’, their full-length debut that delved into issues of self-discovery, and liberation from limitations and self-doubt. It also happened to be one of the best collections of propulsive, immersive and tough-minded techno tracks of that year.

DJ Mag recently caught a TYGAPAW set at Brooklyn’s Good Room. Taking the reins from Lauren Flax at 1 AM, sporting a black cap and hoodie (and a mask — Omicron was raging through NYC at the time), McKenzie rifled through a driving mix that took in music like LSDXOXO’s neo-ghetto-house banger ‘Sick Bitch’, DYEN’s hardcore-esque ‘Jack’ and Beaker’s B’more-tinged ‘Hype (Funk)’, making the occasional pop-ravey pitstops for cuts like the ATB version of Miss Jane’s ‘It’s a Fine Day’. It was a set of pure party music, welcoming and jubilant.

A few days earlier, DJ Mag had met up with McKenzie on a brisk Brooklyn afternoon. Meandering through Bedford-Stuyvesant, the search was on for a quiet space to chat; we finally settle, despite the 40-degree chill, on the back patio of a laid-back café. The past year had been a busy one for McKenzie release-wise: there was a beautifully hymnal rework of ‘New Moon’, a song from the composer and performance artist Lyra Pramuk’s ‘Delta’ LP, and a reverberating 12 minutes of experimentation called ‘Volubilis’ on ‘Explorations in Analog Synthesis, Volume II’, a compilation put together by Moog that boasted aural R&D from the likes of Paula Temple, Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith and Galcher Lustwerk, among others.

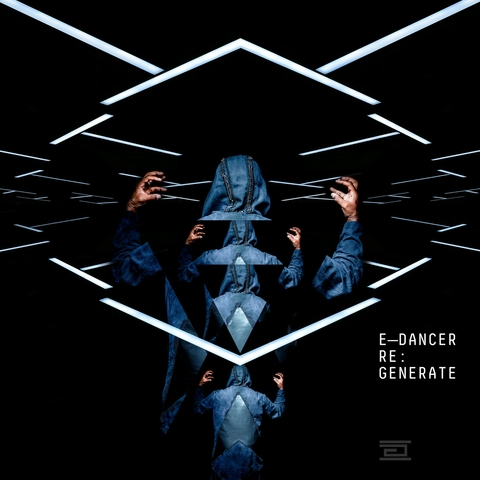

Among the higher profile projects were ‘Diffusus’, a buzzing, intense cut on Berlin techno institution Tresor’s 30th-anniversary compilation. It was a standout on an album that also featured contributions from heavyweights Juan Atkins, Daniel Bell, K-HAND, Robert Hood and Joey Beltram. Then, there was the TYGAPAW version of E-Dancer’s classic ‘Banjo’, off the ‘Re:Generate’ remix album — the howling, chiming cut is one of the LP’s highlights, no easy feat when you’re among names like DJ Bone, Robert Hood and DJ Minx. According to McKenzie, they haven’t had to seek out that kind of blue-chip work; instead, the work has come to them.

“I mean, yeah, it was a very big surprise that Kevin wanted me for a remix,” McKenzie says, referring to Kevin Saunderson, the Detroit pioneer behind E-Dancer. “It was such an iconic project. But they sought me out, like everything else that came in the past year. It’s because I’ve just been doing the work and investing a lot of energy, and people have just been really responsive — so the theme of this past year has been ‘TYGAPAW: It’s time.’”

The current Peak TYGAPAW era was set into motion by ‘Get Free’, released by Mexico City–based label collective N.A.A.F.I.. But McKenzie’s traveled a long, meandering and sometimes difficult path to get where they are today.

As a young child, they were attracted to music, much as any kid is — but in MacKenzie’s case, the pull was a bit stronger. “I think I had more than what’s the average interest,” they say. “I have two brothers, but I didn’t see them as consumed as I was with music, and with wanting to do musical things like play instruments. Like, I was very persistent of asking my mother for piano lessons — which I did not get — and I don’t think children generally beg for piano lessons.”

Commercial radio was the main source for music, so reggae, dancehall and Top 40 pop made up the bulk of McKenzie’s listening diet. “I think the first voice that really pulled me in was Whitney Houston, who became a bit of an obsession,” they say. “She still is! Tina Turner was a big one for me, too. But lot of what you’d be exposed to was really bad. Rick Astley, ‘Never Gonna Give You Up’ — I remember that song playing constantly. You couldn’t get away from it.”

Anything that could vaguely be considered underground dance music was far in the future. “The only electronic music that I got at the time was presented in a pop form, like C+C Music Factory and Haddaway.” It would have been hard to find anything else in Mandeville — and even if it had been available, it would have been frowned upon.

“Jamaica is very conservative,” McKenzie says. “It has the most churches per square mile — there’s a church on every block — and individualism is not really a thing that is appreciated. I mean, you can be an individual, and you can like quirky, strange things — but you’re going to be ostracized for that.”

The emphasis on conforming to conservative societal norms extended to McKenzie’s time in Jamaica’s education system. As someone who was AFAB, (assigned female at birth), they were sent to an all-girls school, where the students were indoctrinated into ultra-traditional gender roles. Girls were taught “to serve”, as McKenzie’s fellow Jamaica-born artist Grace Jones put it in the Underplayed doc, and told that they’re meant to be housewives, teachers or nurses.

“Even just thinking about the tools they equip you with when you go to an all-girls institution....” they begin, anger at the system still evident. “There’s a disservice that they will do to children in the islands, right? This is not just a Jamaica problem — this is a British colonial problem. It’s a very conservative, restrictive environment. It’s not right to teach kids that if they’re born with certain genitalia, then their purpose in life will be to serve somebody else. That is what you’re indoctrinated into. And I was just like, ‘Uh, excuse me?’ In my deepest of souls, that felt disruptive to me, and I was just like, ‘Fuck, no. This is bullshit.’ I was just like a little rebel punk.”

Luckily, McKenzie’s mother, an OB-GYN, lent a degree of support (even without those piano lessons). “She wasn’t going to teach me that I’m going to be submissive, like I’m going just learn how to clean silverware and wash, and be of service to somebody, and that will be my purpose in life, like what I was being taught right in high school,” they say. “You could just tell by her example. Where she comes from, a part of Kingston that is as hard and difficult as it gets, there really are no people who just become OB-GYNs. Her becoming a doctor helped to change and shift our path. I observed her enough to be like, okay, there are options, and I have to stand up for myself.”

McKenzie’s first entry into creative life came not through music, but via drawing. “Just as a form of expression,” they say. “I would listen to music, and I would start drawing, and I just did that relentlessly. But nobody would care; that’s not a practice that we had a lot of space to develop that kind of skill, and it’s not encouraged. So here I am with this quote- unquote ‘talent,’ but with no one to say, ‘Oh, you could do this with your life.’”

McKenzie is still active in visual arts — their current work, bold and expressive, was recently part of a group show called Dance Trans* Revolution at NYC’s apexart gallery and performance space, for instance.

“I had enough emotional intelligence as a child to say, 'hey, this might not be it'. How could I be so self-aware? I think something was working through me, maybe something ancestral”

Escape To New York

McKenzie’s artistic talent got them accepted, in 2002, to Parson’s School of Design, and they made the life-changing move from Mandeville to Brooklyn. As they saw it, the relocation was as much a chance to get out of Jamaica as it was to attend school. “I had enough emotional intelligence as a child to say 'hey, this might not be it',” they say. “How could I be so self-aware? I think something was working through me, maybe something ancestral.”

Like many immigrants, McKenzie’s image of America was formed by American television and American culture — notably, ’90s-era MTV. As it would for most people in their late teens, that kind of image added to the excitement of the move — but the move almost didn’t happen.

“9/11 had happened right before I came, and I think they had limited it to 20 student visas, or some crazy number like that, for all of Jamaica,” McKenzie explains. “I try not to complain, but I feel like that kind of bureaucracy is another form of systemic racism.” But luck was on their side — they managed to gain entry as a visa lottery pick.

For McKenzie, moving to NYC was eye-opening — even seeing something as simple as people’s love for the aforementioned Grace Jones felt like a revelation. “I grew up hearing that Grace Jones is ugly, that Grace Jones is mannish, that Grace Jones is uncouth,” they say. “In Jamaica, there’s all this misogynoir and homophobia and xenophobia attached to her. She epitomises this fear of something that doesn’t really fit right in. And when I got to New York, I found out everybody loves Grace Jones: Grace is the mother, Grace Jones is it! Imagine that if when I was young, I had been exposed to Grace Jones as an empowering figure in music and art — that could have helped in my journey.”

At Parsons, they studied communication design: “The practical side of art and graphic design,” as McKenzie puts it. “That’s always the compromise: You can be an artist, but you have to earn money. And communication design in a corporate setting is a way you can earn money. I’m like, well, that’s going to send me to my grave by age 40. But I still played the game — like, yeah, I’m here, I’m happy to be in New York, so I’ll do this.”

Resigned to do what they had to do to stay in the city, McKenzie dove into schoolwork, even though they weren’t particularly inspired by their studies. There wasn’t much room for a social life — but they did fall in with students at Parson’s affiliated music school. “I was always hanging out with the jazz kids, and I’d go to their gigs,” McKenzie says, “and I dated a jazz musician at that time, a trumpet player. I was fascinated because I wasn’t really like exposed to jazz growing up, so I spent so much of those years just taking in these new musical experiences and becoming obsessed. The freeform experimental aspects of how they perform fascinated me.”

Still, it would be years before McKenzie would personally become actively involved in music production. “I call those the dark years,” they say, “where I was not able to do anything creative, because I was just struggling to survive. It was years of being in limbo, of being undocumented. I was literally a stuck human being, but stuck in a city where we can get swallowed.”

The hustle included work in Caribbean bars. “I mean, nobody can talk to me about working hard,” they say. “I know what that means. I know what that feels like. I know about working for $40 on a shift that starts from 6pm and ends at 4am. And that was my life during that time.”

But not quite their entire life. There was one other thing — McKenzie had picked up a guitar right after finishing up at Parsons. “There were years of no pressure with it, just experimenting with it and figuring it out,” they say. “I was just excited about playing an instrument, not about knowing if I was actually going to do something with it. It was like when I had picked up a pencil and paper and started drawing — guitar was exactly like that.”

Meanwhile, their computer died, and without the means to afford a new one, any chance of landing design jobs had evaporated. “I was like, alright, I’m just going to try and figure out as best as I can how to get through this period,” they recall. As luck would have it, McKenzie got some help in that process when they met their future bandmate, Erika Buestami, aka Enki. “She had gone through a similar situation — she’s Indonesian and Australian — and she was like, ‘you know, we’re gonna figure this out,’” McKenzie explains. “She was one of the people who boosted my morale, who helped me in terms of not getting swallowed by the darkness.”

Lost In Music

In 2010, the two, along with another friend, Katy Walker, formed My M.O., a group that slotted into the space between synth pop and catchy indie rock, with McKenzie’s guitar nudging the band’s sound towards that latter. (Paste Magazine, slightly misleadingly, opined that the band was for fans of “Kenna, Ladyhawke, Friendly fires, Santigold, Lily Allen.”) The group had a degree of success, even releasing a full length album, ‘Bonfire’, in 2011.

“That period saved me,” McKenzie says. “Just having a purpose, you know? Playing in a band was making me feel a lot better than sitting at home and trying to figure out where the next meal is coming from. Riding my bike to rehearsals, my guitar strapped to my back — it was great.”

But as is usually the case with bands, it was only a temporary distraction. “My M.O. lasted maybe three years? When you’re in your 20s, and you’re living hand-to-mouth, time passes very slowly but very fast at the same time,” McKenzie says. “But we got some shit done. We made some music videos. And we certainly played a lot on the Lower East Side circuit — there were a lot of places to play back then.”

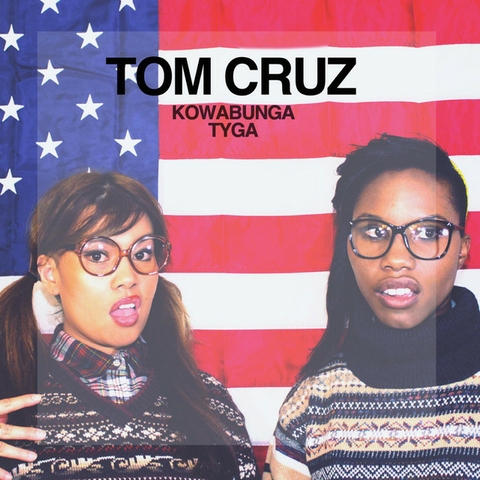

There was another musical outlet to distract McKenzie from the difficulties of everyday life, and it was a doozy — a duo with Enki called Kowabunga Tyga, with a sound that could loosely be termed “attitudinal electro rap.”

“The two of us [Dion and Enki] were really into joking about things with that one,” McKenzie says. “I was just discovering Peaches and badass shit like that. And at that time, things like Das Racist were really big, and we were friends with another group called... something about a handjob?” (It was Hand Job Academy, another Brooklyn rap outfit). “They were into the comedy aspect, and we were too. We wanted it to be a fun, free flowing, who-the-fuck-cares thing.”

Soon, there was yet another musical endeavour — Fake Accent. Described as “a platform and collective of queer visual artists, DJs and music producers to create intentional and immersive spaces in and outside of the club”, when it launched in 2014, it was mainly as a party. At the urging of Enki, those parties marked McKenzie’s first forays into the DJing arts.

“I definitely had rock-star aspirations,” McKenzie says, “but I never had DJ aspirations. In my mind, DJing didn’t feel like it was accessible to me. I mean, I knew a ton of DJs — and they all were all AMAB, all male. But Enki gave me a lot of empowerment and encouragement for me to do it, to keep going. She was one of those people who came into my life to be to be that angel — like, ‘You’re on the right path, you’re doing great things and you’re a fucking talented person.’ So when she told me I should DJ, why not? She let me know about Serato DJ and these little controllers that I could use to get started.”

At first, McKenzie was spinning “music that just feels good,” as they put it. “Things like TNGHT [a project from Hudson Mohawke and Lunice], James Blake’s 1-800 Dinosaur project, lots of Kaytranada remixes. Oh, Little Dragon — I would play Little Dragon a lot!” But the discovery of a different kind of music — the unabashedly queer, undeniably addictive sound of ballroom — changed everything.

“My introduction to ballroom was Zebra Katz’ ‘Ima Read’,” McKenzie recalls, “and it was game over. I was like, I’m not playing anything else. Let me know more about this genre.” McKenzie was friends with Andre Singleton and Justin Fulton, the creators of The Very Black Project, an initiative that celebrates Blackness through social activism.

“They would invite me to these Kiki balls at their house, and then I started to learn more about ballroom culture,” McKenzie says of that time. “I just was feeling it. I discovered MikeQ, LSDXOXO, Byrell [The Great], DJ Delish, all that. That whole period was an epiphany.”

It was around this time that McKenzie began working on music that would eventually be released under the TYGAPAW moniker — but the production seeds had been planted well before. “I had taken an audio sound-design class that taught me a bit of Pro Tools. Pro Tools is really hard — I was like, that’s a really steep learning curve, y’all,” they say, laughing.

They had also gotten advice from an old friend from school, the musical polymath Jesse Boykins III. “He’s a person who’s important to my journey, because he was actually one of the first people who encouraged me to pursue music.” And of course, playing in bands didn’t hurt. “Being in the studio, I was kind of observing and learning things like Logic.”

Getting their hands on Ableton’s production software was a key step as well. “Ableton enabled me to change my view on producing because it became way more enjoyable,” McKenzie explains. “I could be more experimental; I wasn’t so tied to the linear grid. Everything was more performance based, and as a musician, that interested me.” (Ableton is still their DAW of choice.)

But it would be a few years before their work would see the light of day. “I was just working on my own, strengthening my legs, like learning how to swim,” McKenzie says. “And you’re not going to release the shitty things that you make in the beginning anyway — and yeah, I made a lot of shitty things!” Still, they were making progress. “In retrospect, I think I was excited about realising there was a possibility that I could actually do this.”

“It was very important that my music needed to be a cathartic sort of vessel, a vessel that would let me really tell the truth and share certain experiences sonically”

Release Yourself

The first TYGAPAW EP to see the light of day was ‘Love Thyself’. Released in late autumn of 2017, it was a remarkable debut, alternating between emotive ambience (the moving ‘Tried’) and ballroom thwack (‘Who I Am,’ featuring an assertively forceful vocal contribution from Baltimore artist Abdu Ali). With ‘Love Thyself’, McKenzie was already exploring the themes, succinctly summed up by the EP’s name, that define their later work. “Do what feels good, and do what feels free,” as they put it. “It’s about living life in your authentic self, about living in your truth. There are no rules.”

There was soon more. The thumping ‘Applause Ha’ appeared on the Mixpak label’s ‘2017 Holiday Bundle’ compilation, while ‘Black Womxn Experience’ appeared a few months later on Discwoman’s ‘Physically Sick 2’. ‘Black Womxn Experience’, in particular, was a stunner, its shimmering ambience interlaced with fragments of interviews from a New York Times mini-documentary, A Conversation With Black Women on Race.

“The interviews were conducted with young women and their mothers about their first experiences with being told that they were othered or not accepted,” McKenzie says. “That’s a really vulnerable position to be in, and it’s empowering to know and to share those stories. I wanted to shed a little light on my childhood and some of the limitations that I was exposed to, and that I know are commonly projected onto other young girls.”

As with pretty much everything McKenzie puts out, it was music with a message — a message that stems from the personal, but that’s universal in scope. “It was very important that my music needed to be a cathartic sort of vessel, a vessel that would let me really tell the truth and share certain experiences sonically,” they say of the track.

‘Handle with Care’, released in spring of 2019 on the Fake Accent label, was “a personal tale of my journey as a queer black Caribbean womxn living in the NYC”, as McKenzie wrote at the time. “Coming to terms with unsettling truths about the emotional abusive nature of my Jamaican upbringing and the normalization of domestic violence as it transfers generation to generation without being challenged”. It was also the toughest music they had yet released, another step in McKenzie’s evolution as a producer.

Just before the release of ‘Handle with Care’, McKenzie had a string of DJ dates in China. One of the stops was in Hong Kong, where they had something close to an epiphany. “I got to hear [the veteran Detroit electro and techno mainstay] DJ Stingray play in Hong Kong, in a warehouse,” they say, still reveling in the experience. “It was otherworldly. I was like, I want to play like that! I want to make that shift.” Before that, other than ballroom, McKenzie’s exposure to modern electronic club music had been largely through the big (and white) names.

“Chemical Brothers, Prodigy — I still fuck with them — Daft Punk, even Justice for a minute,” they say. “But then, all of a sudden, I’m discovering stuff like Scan 7 and Drexciya. I’m like, oh my god, excuse me? Why don’t we know about these figureheads? We’re very much a part of this rise of techno,” they continue, speaking of Black artists, “but if you just take it at face value you wouldn’t know this. I found my own way to techno without knowing this, instinctively — and then it was like, okay, maybe that’s why I like it. It literally is our own music.”

“For my Black, queer, trans, non-binary listeners: I’m making this music for y’all. This is Black, queer, trans, non-binary liberation music. But this is universal as well. It’s about owning who you are, unapologetically. It’s music for the revolution”

‘Ode to Black Trans Lives’ came out in June of 2020, just after the murder of George Floyd and during the height of the Black Lives Matter summer. The three-track release was a collaboration of sorts with the scholar and advocate D-L Stewart, with excerpts from Stewart’s TED talk, Scenes from a Black Trans Life, providing the EP’s narrative focus. The release was inspired by the events of that summer, in particular a pair of rallies that took place in Brooklyn on June 14th — a BLM march at Grand Army Plaza, and a Black Trans Lives Matter March steps away at the nearby Brooklyn Museum. To McKenzie, it was evident that there was little cohesion between the two groups.

“We’re ultimately fighting the same battle, but there’s no unity within that,” they explain. “We’re literally still oppressed within our communities — trans, non-binary and queer Black individuals are just completely ostracised: ‘You’re others, and you’re outside of this community.”

“You know how powerful ‘Ode to Black Trans Lives’ is?” McKenzie continues. “I made that in a day. The power of that energy that I have to fight against oppression, it was just embedded in me. And as an artist, I will never ever stop.”

Immediately following the creation of ‘Ode to Black Trans Lives’, McKenzie got to work on what would become their debut LP, ‘Get Free’. “I knew I wanted to do something cute, and I knew I wanted to create a sound of liberation,” they say. ‘My thought process was like, you start somewhere and you just go there. I really didn’t overthink it; it was all energy at the time.”

McKenzie’s previous work had been produced at home — but for ‘Get Free’, their friend, the engineer Loric Sih, gave them access to a production facility. Being in a real-deal studio opened up the sonic possibilities: “I could really dive into making techno the way I envision it,” they say. It shows in the results, with cavernous beats and bass anchoring an immersive ambience that flows through the tracks like vapour.

There was a kind of manifesto, written by McKenzie, that accompanied the November 2020 release of the LP. “‘Get Free’ explores what it is to actively dismantle imagined limitations, to eradicate the bondage of self-doubt, to forge ahead with love and light, to liberate the body and mind,” it reads in part. “Once the vision is actualised, we gain connection, and ultimately we get free.”

That message is augmented by three swooning tracks that feature the spoken-word vocals of artist, writer and “full-service griot” (to quote from her Instagram profile) Mandy Harris Williams. “Some of us had to get free, and some of us might,” Williams explains in the ‘Get Free Intro’; “Relish in those waves, we stand only to gain connection”, she intones on ‘Overland Interlude’.

“I was aware of Mandy’s work and I realised that I would love for her to be involved, to carry the narrative aspect of the album, because I’m not the most confident in my voice.” McKenzie says. “A reason that pushed myself forward into music making in general is because I was a very, very shy child. I was not encouraged to be expressive. So it’s like, ‘okay, I’m just gonna sit and chill and not be heard’. But my mother was this personality — the extrovert, the light, the beacon. I saw a bit of that in Mandy. That voice is really strong and powerful. The way she writes, she articulated all of my thoughts in terms of the music’s concept.”

The album’s cover art, shot by McKenzie’s partner Avion Pierce, who also shot their DJ Mag cover photos, is as strong as the music and the message. It depicts McKenzie nude, from behind, bathed in ochre light and exuding strength. “How incredible are Black femmes? They are unmatched. And that’s kind of my point,” they say of the cover art. “The process of making that album is another affirming foot in the door of our own path. I’m dismantling self-doubt, that internal voice that has been implemented by someone else. I’ve done the work to heal and grow, and to build as a person so that I can overcome those challenges, and to be the fully formed artist that I know I am.”

That dismantling of self-doubt has been one of the defining aspects of McKenzie’s career, and will likely continue to be so. Both the concepts and the music itself have become sharper, their focus tunneling down into the essence of their message.

Setting It Free

As a result of Covid, gigs were impossible after the album’s release — but McKenzie nonetheless got a taste of what the release of a well-received album can mean to a career. “There were so many requests for interviews,” they say. “And once things did open a little, I saw the tail end of the fever. It wasn’t the brunt of what a whole full tour would have been, but it gave me a glimpse of the madness.”

McKenzie’s forays into that madness seem to be continuing unabated. Among other things, ‘Get Free’ will finally be getting a vinyl release on the Mister Saturday Night label, due out in April. “That album lives on,” they say with justified pride. “It was released in a pandemic, but it’s expanded like a phoenix and it’s flying somewhere else. It has wings.”

There’s work, of course, on a follow-up album — it’s “very hardware focused,” they say. And there’s a recently announced residency at the New York renowned arts institution ISSUE Project Room, where McKenzie will be working on an unlikely sounding endeavour — a techno opera.

“The reason why I’m taking on this great feat, this adventure into territories unknown,” they explain, “is just that I’m a person who’s always willing to learn to grow, expand, explore and experiment. Coming from where I come from, I’ve had very limited exposure to opera, and I think that’s the intriguing aspect of it. I’m like, how can I dismantle what opera really stands for? It’s about elitism; it’s about what marginalised people cannot have access to; it’s about where the rich get to spend their money and have a night out. So I chose the opera format because of its legacy, and how it’s presented. And why not use techno as a soundscape to build that world?”

The New York Times recently ran an opinion piece titled The Radical Normalcy of a Trans ‘Jeopardy!’ Winner, revolving around the quiz show’s recent super-champ, Amy Schneider. The piece, penned by the author Jennifer Finney Boylan, includes a line that resonates: “Allowing a multitude of ways to exist in the world seems like a very good way of setting people free.” It’s a sentiment that McKenzie echoes. “There is no blueprint for me personally,” they say. “There’s no blueprint for somebody who looks like me, for who embodies me. So why not just be as honest as possible? Why not do what feels good and what feels free? There are no rules. They lied, y’all — there are no rules! You don’t have to be a certain way to be accepted.”

Asked if there’s one message that they hope that people get from their music, McKenzie thinks for a few seconds. “I just want to create harmony in the world,” they finally say. “That’s my intention. For my Black, queer, trans, non-binary listeners: I’m making this music for y’all. This is Black, queer, trans, non-binary liberation music. But this is universal as well. It’s about owning who you are, unapologetically. It’s music for the revolution.”