How Double 99's 'Ripgroove' lit the fuse for speed garage in the UK

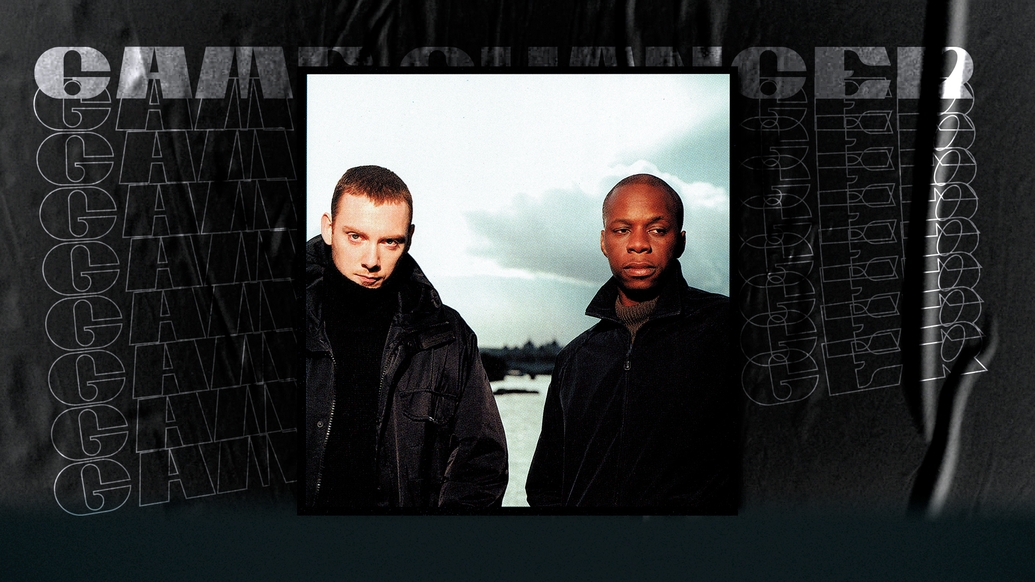

Double 99's ‘Ripgroove’ helped ignite the speed garage scene in the late '90s, and went on to gatecrash the pop charts and break down mainstream doors for sub-rupturing club tracks. Amid a renaissance of UK garage, Rob McCallum speaks to Tim Deluxe and Omar Adimora about the game changing track’s timeless quality

Few tracks have had such a long-lasting impact on UK dance music culture as Double 99’s ‘Ripgroove’. An instantly recognisable blast of tight, shuffling drums and chopped up vocal samples, all built around the repeated delivery of that sub-rupturing speed garage bassline, it has repeatedly returned to relevance in the 25 years since its initial release.

Having played a huge part in helping detonate a scene which The Guardian newspaper described as “Britain’s richest cultural movement” at the turn of the Millennium, the track’s lasting legacy has been brought back into focus again as the pendulum that is fashion swings back towards UKG.

In the years following ‘Ripgroove’’s release, the sound of UK garage would come to dominate the charts and commercial radio, and breathe new life into the British music industry. Part of the beauty of the impact of ‘Ripgroove’, though, is that despite eventually becoming a commercial success (more on that later), it’s a club record made by club DJs, and for club DJs. Produced by Omar Adimora and Timothy Liken, AKA Tim Deluxe, under their Double 99 alias, it was originally released as part of a double-pack on their label, Ice Cream Records, in 1997. But to tell the full story of ‘Ripgroove’, you have to go back to the early ‘90s, when a teenage Liken was working at Time Is Right Records on Chapel Market in Islington, London. It’s a record store that Adimora, who played at clubs across the city at the time, visited every week when new records and imports arrived, buying a mixture of US house, US garage, jungle and UK rave sounds.

“When you got halfway down Chapel Market, you could start to hear the bass, and the kick,” he explains. “Time Is Right was like a church to music; a safe-haven of like-minded individuals that were either producers, wannabe producers, or budding DJs. It felt like a kind of community centre.”

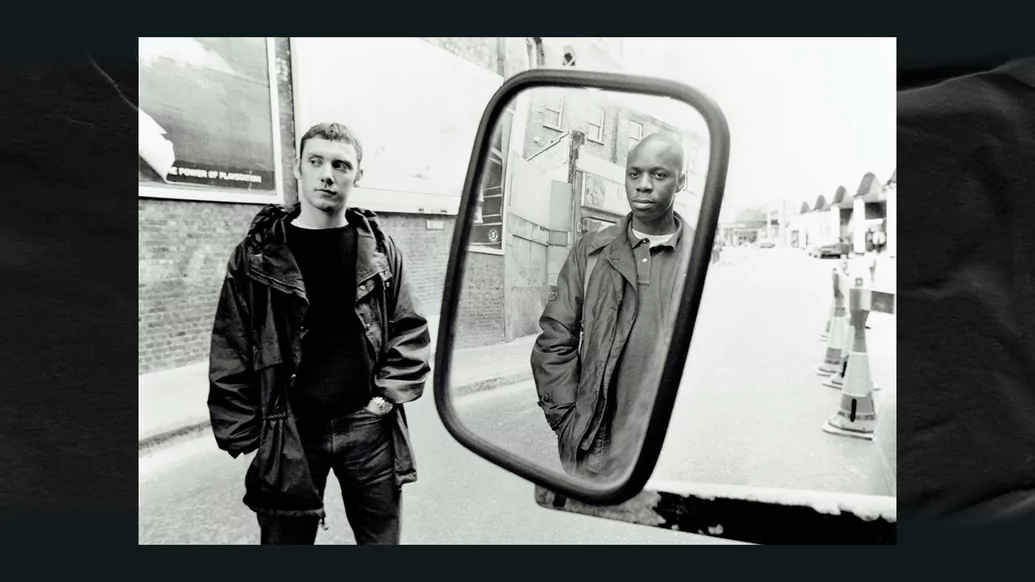

The pair quickly formed a bond over the music they loved, analysing records and their structure together from artists including the Smack collective, Eddie Perez and Kerri Chandler. Adimora had grown up in England with Nigerian heritage, while Liken had moved over to London as a child from Northern Ireland. “We’re effectively second generation immigrants. And I guess that brings a mixture of cultures, sounds and vibes,” Adimora explains. “That’s why we worked so well together at the very beginning. Because we brought everything together. It came from our parents that landed here at a time that there were signs on doors saying, ‘No Blacks, no dogs, no Irish’. And now, we’ve moved through that, working together to a time when it’s like, ‘More Blacks, more Irish’. It’s amazing.”

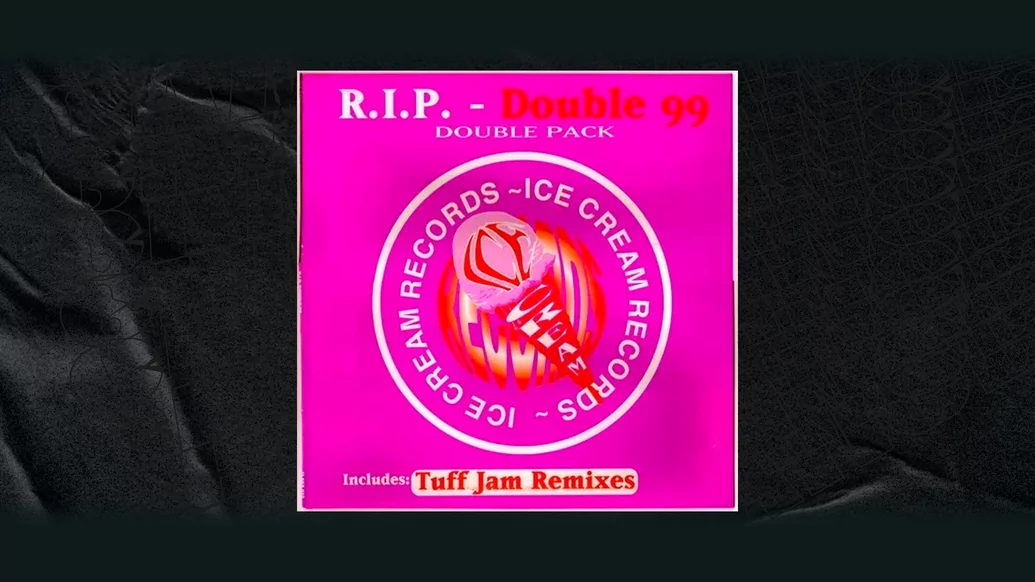

In 1995, Adimora and Liken, alongside Boogie Beat Records founder Andy Lysandrou, set up Ice Cream Records as a platform to put out the pair’s music under a variety of names, including R.I.P. Productions and Guess Who?. From their first studio, in the basement of an estate agents on Holloway Road, the pair quickly saw creative success with bumpy garage cuts including ‘Pick Me Up’ and ‘I’ve Been Misled’.

“When we were looking for places after we finished working in the studio in Holloway Road, I thought, ‘Hold on a minute — I’ve got a kitchen I don’t really use. Let’s put a studio in there: that’s a good idea’,” Adimora laughs. “We cleared everything out. And that’s how our full-time studio partnership commenced, in the kitchen of my flat in my parent’s house.”

As the first releases were landing on Ice Cream, the pair were also immersed in London’s after-hours Sunday scene, playing and dancing at venues including The Frog & Nightgown on Old Kent Road and Gass Club in Leicester Square. “That was where the pitched-up vibe came from, because people were wanting to stay awake,” Liken explains. “People wanted energy,” Adimora agrees. “A lot of the time we’d have sessions the night after going out, so we [would] still have that energy.”

“It’s way heavier and darker than anything we’d done before. But there’s a lot of different influences coming in” — Tim Liken, AKA Tim Deluxe

In 1997, Adimora and Liken decided that for their 10th Ice Cream release they would deliver a double-pack. Their studio sessions at the time were also heavily influenced by the sound Armand van Helden had been experimenting with on tracks like his ‘Armand’s Dark Garage Mix’ of Sneaker Pimps ‘Spin Spin Sugar’ — which would eventually become known as speed garage, or plus-8 — as well as music being played on pirate radio stations like Kool FM. “There was already a darker sound working in clubs,” Liken explains. “All the earlier Ice Cream stuff was quite musical and going back to a love of American garage, [with] jazzy chords. This was a chance to throw that out the window and go for it.”

When the pair sat down to make ‘Ripgroove’, they initially built a drum pattern on an E-mu SP-1200 drum machine using samples from a disk the legendary DJ Disciple had given to Liken on a recent trip to America. “People used to swap disks,” he smiles. “It wasn’t the days of sample packs... everything was on a floppy disk.”

The objective from there was simple: “Let’s make something dark and big with a [huge] bassline,” Liken smiles. The instantly recognisable riff is built from two parts, one from a Yamaha DX100, layered with another from a Juno 106. “The Yamaha DX100 looks like a toy,” Adimora explains. “But it’s got buttons you could punch out to select certain layers or frequencies. I was just hitting it, and the speakers really started to vibrate. Tim had the drums running, and it all really worked — the whole speed garage bass just kind of happened.”

The original Ice Cream release of ‘Ripgroove’ features a more sparse arrangement of MC Top Cat, alongside vocal samples and chops from CJ Bolland’s ‘Sugar Is Sweeter (Armand’s Drum ‘N Bass Mix)’, the ‘Kelly G Bump-N-Go Vocal Mix’ of Tina Moore’s ‘Never Gonna Let You Go’ and DJ Gunshot’s ‘Wheel ‘N’ Deal’. The chord sequence from the bassline is interpolated from a Mozart composition (Piano Concerto No.24 in C minor, K491, for the trainspotters). “It’s way heavier and darker than anything we’d done before,” Liken smiles. “But there’s a lot of different influences coming in.”

The pair namecheck a number of people as being pivotal to the success of ‘Ripgroove’, and one of those is the first person to ever hear the track, then Twice As Nice resident, DJ Spoony. A good friend, he stopped over at their studio shortly after they’d made ‘Ripgroove’ to see what they had been working on. “We played it, and he was like, ‘You lot are mad!’” Liken laughs. Spoony asked if he could cut a dubplate at Music House to road-test at Twice As Nice the following Sunday. Liken still wasn’t old enough to get into the club due to the night’s strict over 21s door policy, so Adimora went down to gauge the reaction.

“The crowd [there] were ruthless,” Adimora explains. “If they didn’t like something, you’d get booed. You could even get an empty champagne bottle lobbed towards the decks.” Spoony played it when the club was packed at around 1 AM. “I was so nervous. I started hiding behind the speaker box. [But] BANG, when it kicked in, people started screaming, throwing their drinks up in the air rather than at Spoony. I remember calling Tim and saying, ‘I think we’ve got a monster here’.”

Another person the pair say they “owe a great debt to” for the track’s success is their label manager, Lysandrou. He was the person behind the imprint’s now iconic artwork and, as a one-man self-distributed operation, would drive his Mini Metro up and down the length of the country delivering records straight from the pressing plant. He even, as what turned out to be a masterstroke in marketing, delivered empty sleeves of the double-pack to shops ahead of its release. As ‘Ripgroove’ was all over pirate radio channels by the time the pressing landed, stores stayed open late to accept the delivery as they had so many people waiting to buy them.

“I remember him saying, ‘This is flying. It’s really, really flying. There’s a real buzz!’” Liken smiles. Shortly after, Nick Raphael, an A&R man who the pair knew from his previous work as a club promoter, DJ and producer, got in touch. He had set up a label called NorthWestSide Records at BMG. His first signing since joining was a young Jay-Z, and he wanted Double 99 to be the first release on a dance imprint under BMG called Satellite Recordings.

As the record was blowing up in clubs — not only with DJs on pirate radio and in London’s after-hours clubs, but also outside of the M25 at clubs like Niche in Sheffield as the bassline scene was starting to form, and in superclubs like Cream and Gatecrasher — a bidding war ensued between labels. “With Nick, he had a history,” Adimora explains. “He understood the energy and the vibe of the record.” By May, it had been released under licence to BMG.

Despite the continued success of ‘Ripgroove’ in the clubs following its release on Satellite — which also saw it spread out of the UK to get regular rotation through the summer in Ibiza — commercial radio were resistant to playlisting it, and it initially scraped into the UK Singles Chart Top 40 at number 31. “We were all really disappointed because the record was just getting bigger and bigger and bigger,” Liken explains.

“It was maybe too urban, or too Black, and didn’t suit the narrative of playing stuff that was not so aggressive in their eyes,” Adimora adds. Although the duo were disheartened, Raphael refused to give up on what he believed was a hit record. He insisted they had to go again. “He told us, ‘We’re not going to give up. I think we can do something special with this. We need to have a vocal on it,” Liken explains. So they set to work. “We tried sampling rap records; old school disco acapellas,” Adimora explains. “But nothing seemed to gel.”

It was Lysandrou that suggested looking at the original Top Cat acapella sampled on the first version. They worked out an arrangement they felt worked, but it was beyond the capabilities of their sampler at the time, so their friend CJ Macintosh put them in touch with a Pro Tools operator called MIDI Mike. Together, they created what became the re-released version that landed in October 1997.

During this time, the Double 99 pair found an unlikely ally in the shape of BBC Radio 1 drive-time host Mark Goodier, who had used the original Ice Cream release as his soundbed all through summer. “It showed playlisters their transmitters weren’t going to catch fire if they supported this pirate radio record,” Adimora laughs. The pair, despondent, had gone to New York to spend some time with Eddie Perez. But the second release lit a touch-paper under the record. “It really blew up,” Liken explains. “Nick was on the phone saying, ‘Get back here!’” “The vocal added another texture in terms of commercial acceptance,” Adimora adds. “For playlisters, it gave them one less excuse to not play the record. It felt like a sea change, as it opened the floodgates for other club records.”

“They couldn’t ignore it,” Liken adds. “I’m sure there were people there that weren’t happy about it. But that’s life. It keeps moving.” The pair both add that they have to give it to Nick for forcing the issue. “At that stage, if he didn’t say, ‘We’re going again’, ‘Ripgroove’ might have faded away.”

“Scenes like dubstep, grime, and even drill... without ‘Ripgroove’ kicking down doors of radio, clubs... I don’t know whether [they] would exist. We weren’t the only one. But we were the first to really make an impact” - Omar Adimora

What followed was a series of promotional work and high-profile remixes that culminated, in some ways, with a performance on Top Of The Pops alongside Spice Girls, Michael Bolton, Black Street, Danni Minogue and The Charlatans. It was also presented by Mary Anne Hobbs, another long-time supporter of the record. “I told my mum, and she was in disbelief, asking, ‘What are you doing on Top Of The Pops?’ I’m like, ‘Well, you know that music I’ve been making upstairs in the kitchen...’ It’s the first time in all those years of buying records, turntables, bits of studio kit, and making a racket upstairs that they thought, ‘Our son must have made it’. They were telling aunties and uncles, family back in Nigeria, it was nuts.”

“It was official then,” Liken smiles. The track has gone on to be played, either in its original form, or remixed/edited/bootlegged, by DJs as disparate as LTJ Bukem, Ben UFO, Mary Anne Hobbs, Diplo, Jamie xx, Loco Dice and, of course, a supporter from the record’s initial success on pirate radio through to modern day, DJ EZ. “‘Ripgroove’ was like a godfather to many genres and sub-genres that sprung up in the years after,” Adimora explains. “Scenes like dubstep, grime, and even drill... without ‘Ripgroove’ kicking down doors of radio, clubs... I don’t know whether [they] would exist. We weren’t the only one. But we were the first to really make an impact.”

“It dipped in the early noughties,” Liken adds. “It was weird. It went away. And then there was a whole new generation of people who discovered it.” “It [shows] ‘Ripgroove’ is bigger than Tim and I now,” Adimora adds. “It’s gonna outlive us. It dips and fades over time and just comes back.” “In some ways it isn’t our record anymore,” Liken agrees. “It belongs to everyone.”

The most obvious of the moments that have brought the record back into focus recently is when SHERELLE dropped the Fixate refix of ‘Ripgroove’ during her live stream at Boiler Room’s Bass & Percs Special in 2019. “The thing I love about these versions is that no one from our side asks anyone to do them,” Liken explains. “We’re not forcing the issue. These are all organic situations.”

He says he hadn’t even heard of SHERELLE or Fixate when the moment went viral. “I remember my phone bleeping and messages and emails coming in. Someone sent the link to the clip and I was like, ‘Wow’. I’ve never seen energy like that. It was like a cauldron.”

The remix went on to get an official release via Ice Cream, and the pair say there is an interesting full circle to Fixate’s version. “It’s almost like he reclaimed it for the jungle scene, because that was our original influence,” Liken explains. “He really nailed the essence of it. It has that raw energy we were listening to [on] Kool FM back then. These types of things keep happening with the record. And that’s a blessing. It’s beautiful to be part of.”

Adimora smiles. “With ‘Ripgroove’, it’s amazing how a track made in a tiny kitchen has stood the test of time.”