The life of dub visionary Lee “Scratch” Perry through the lens

Dalston-born photographer Dennis Morris became friends with the legendary Lee "Scratch" Perry while shooting in Jamaica in the '70s — a close connection that lasted until Perry's passing last year aged 85. Here, Simon Doherty speaks with Morris about some of the moments he captured of the roots and dub reggae visionary

Dennis Morris has been a photographer since he was a nine-year-old child growing up in Dalston, east London. After learning the basics from a man who ran the church choir, legend has it he sold his first picture — depicting a violent protest in Hyde Park — to the Daily Mirror for £16 at the age of 11. That fee might not seem like a lot now, but this was in the early-1970s, and it was more than his family was earning at the time.

During his illustrious career, he ended up working closely with Bob Marley, the Sex Pistols and Lee “Scratch” Perry. He became friends with Perry, a close connection that lasted until the legendary roots and dub reggae visionary’s passing last year aged 85. Morris’ time with Perry is now immortalised in a book featuring rare and unseen photos of the pioneering producer, and an exhibition — taking place from 27th August to Thursday 8th September at 30 Old Burlington Street London W1S 3AP — which also includes a recreation of Perry’s legendary Black Ark studio.

“I was like this kid who was obsessed with football,” Morris recalls. “But instead of sleeping with a football I slept with a camera. I was obsessed with it. Obsessed.” As he got older, this obsession would lead him on the kind of adventures that most people can only read about. “I was very much into music. In particular reggae music, but also rock. I’d read that in the West Indian community Bob Marley was the new voice of reggae,” he remembers. “Everyone was raving about him.” When Morris was 16, after reading in Melody Maker that Bob was embarking on his first tour — the Catch a Fire Tour in 1973 — he decided he wanted to meet him.

This led him to The Speakeasy Club, a late-night venue in central London which ran from 1968 to 1977. “I didn’t go to school that day,” he says, “I bumped off and went down to the club. I was there at 10 in the morning — I didn't know anything about what time bands did sound checks and shit.” Hours later, it paid off. “I just waited and waited and eventually they turned up,” Dennis recalls. “As they walked up to the door, I said: “Can I take a picture?” Bob said, ‘Yeah man, come in’.

“So I went in, he asked me what it was like to be a young Black kid in England. I asked him about Jamaica. He really took to me for whatever reason. He told me about the tour and asked if I’d like to come along. I said yeah.” The next day Morris went home, packed a bag and went on tour with Bob Marley and the Wailers. “In those days they had a Transit van,” he fondly recollects. “I got into the back of a van and Bob looked back and said, “Are you ready, Dennis?” I said, ‘Yeah, man!’ Click [that became a famous picture].”

By the end of the tour it was Dennis’ pictures that were on the cover of Melody Maker — and an acclaimed career in music photography began. In 1976, he went to Jamaica to do some shots of Bob, who introduced him to Lee "Scratch" Perry. “I was obviously into Perry’s music, so we went to his studio and we just instantly hit it off.”

“When we met Perry at his studio it was really strange. He really talked to me. We became friends over the years. He was very special, he either liked someone or not based on their energy. He was that kind of a person, all about your vibe. And if he didn't like your vibe, he would never communicate with you, he wouldn't work with you. It was all about your energy.

“I think we were both as mad as each other in some ways. Because, you know, when I was younger in the choir, people would call me ‘Mad Dennis’ because I was just so obsessed with photography. I always had a camera with me, I was always taking pictures and they thought that was crazy.

“I knew that I was in the presence of extraordinary people. For me with Bob, I knew from the minute I met him and started talking to him, I was in the presence of somebody very, very, very special. That made me leave home and go on the road. He was like The Pied Piper, there are certain people that have that magic; from the minute you meet them, you’re just enthralled by them. We had a very similar background, Bob never knew his father and I never met my father. He was almost like a father figure for me; he was telling me about Blackness, about Black history and this and that. I didn’t have a father to tell me that kind of thing.

“When I was leaving school, I said I wanted to be a photographer, the teacher told me, ‘Don’t be stupid, there’s no such thing as a Black photographer.’ My parents were like, ‘What kind of job is that? How are you going to make money?’ When they told me there was no such thing as a Black photographer I knew differently, because I’d come across the work of people like Gordon Parks and James van Der Zee — these were the pioneers of Black photography in America. Maybe in England at the time it wasn’t [possible] but I knew that it was possible from what I saw coming out of America.

“It makes me feel good because I want to put something back. Bob always said to me, ‘You have to leave a good trail.’ What he meant by that is if you are a pioneer in something as a Black person, you have to leave a good trail for the next Black person who comes along after you. Because if you leave a bad trail, that person will never get a break. I’ve always been aware of the fact that, you know, I’ve always tried to do the best work possible so that the next Black kid that comes along and walks into a pitch editor’s office, he’s gonna think ‘Dennis did well, so I’m going to give this one a try.’

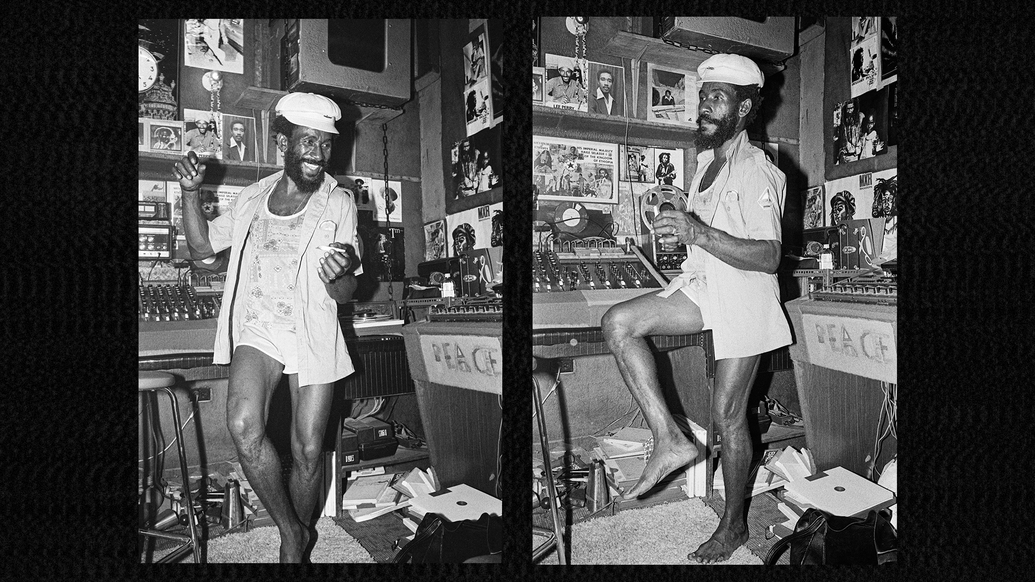

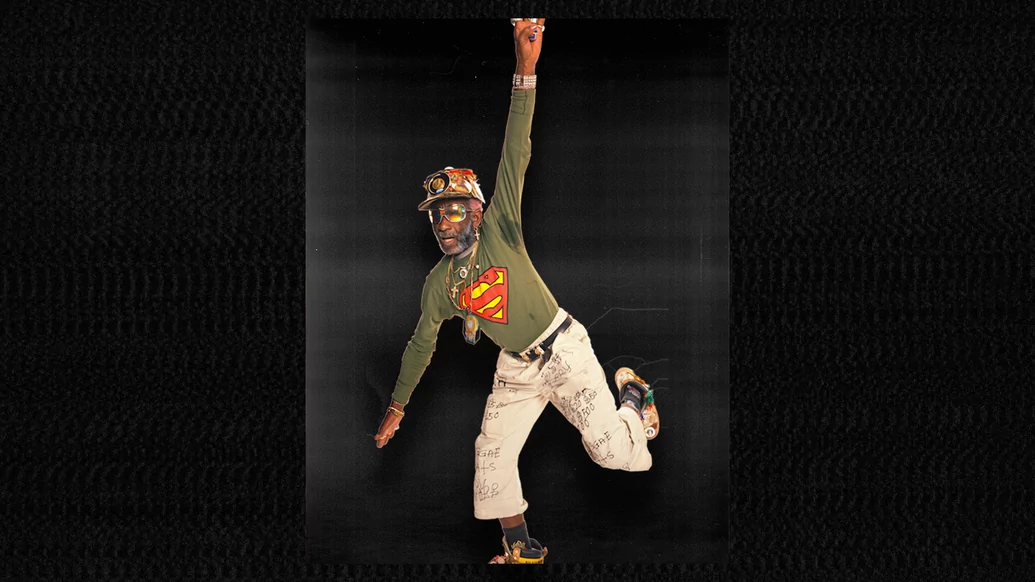

“I’ve never been a big Harry Potter fan in any shape or form, but walking into The Black Ark Studios [Lee "Scratch" Perry’s recording studio in Kingston, Jamaica] was like walking into that magic school. Before meeting Perry I was listening to his music, then when I met him in the studio, it was like walking into the house of magic — that was the place where the magic was made. Then actually witnessing him working was incredible because he never just sat at the desk, he was jumping around all the time. So when you listen to his music and hear all that [mimics reverb effect] he is literally just running up to the board and just turning something. That’s how he recorded.

“In his early tracks he was doing a lot of sampling and such and I can’t remember exactly which song or which album, but in some of it you can hear Coronation Street going on in the background. It was incredible to watch him and that’s why in the pictures of him in his studio what you see is him dancing around having a good time. That’s why when you listen to the music you have a good time because he put a good time into making it. There’s actually pictures on the wall of Barry White, which shows you that he was listening to all kinds of different music, not just reggae. He was into all kinds of stuff.

“There were not a lot of people in the studio. Obviously the musicians were there but he would never let just anybody walk in. He was a very private person. That’s why when Bob died he completely destroyed the studio. He smashed it up because he didn't want anyone to know how he did it [produced the iconic songs]. So he completely destroyed his studio; he smashed everything and set it alight. Then he flooded it and put a load of ducks in there for whatever reason, I don’t know. He left Jamaica, went to New York and legend has it that’s when the scratching came about.

“When I look back at my pictures, no matter how old they are, all the memories come back. I remember the vibe, I remember everything that was going on at the time. It was a great time to be involved in music, you were kind of left to your own devices to do what you wanted. It’s changed completely now, back then if I was doing a gig on stage I would be there throughout the entire show. Now you can only get access to the first three songs — unless you are attached to the band itself. The bands have now become obsessive about controlling their imagery.

“Perry had some major, major hits over the years. For instance, do you remember The Prodigy’s biggest hit? You know the one: ‘I'm gon' send him to outer space?’ Yeah, that was a Lee Perry song. [The main sample hook comes from a 1976 reggae classic called ‘I Chase the Devil’ by Max Romeo, produced by Lee “Scratch” Perry.] That was the song that really launched The Prodigy, that was their first big hit. Even before that, you know the song Chelsea [F.C.] play when they come out? That’s Lee Perry too.

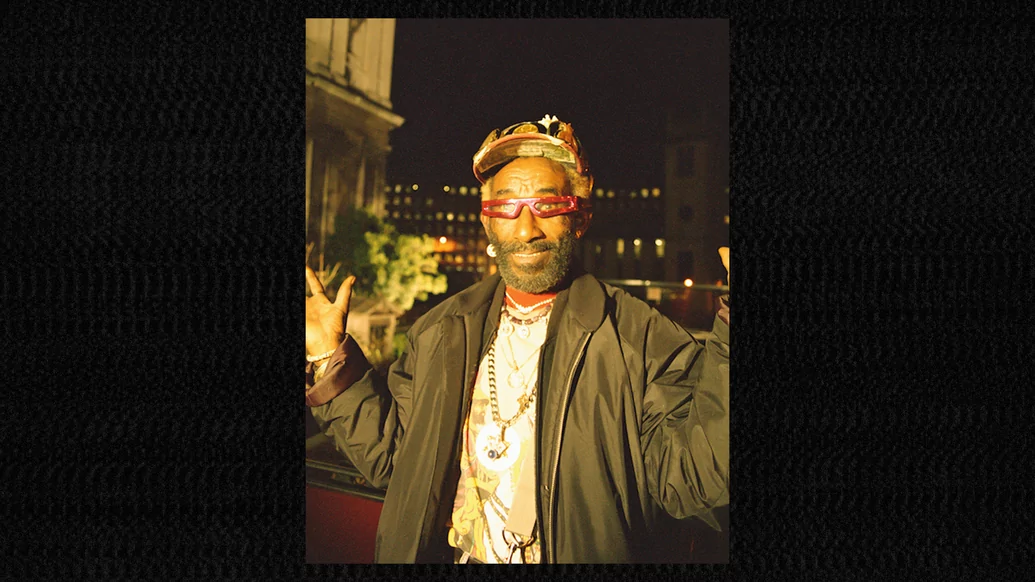

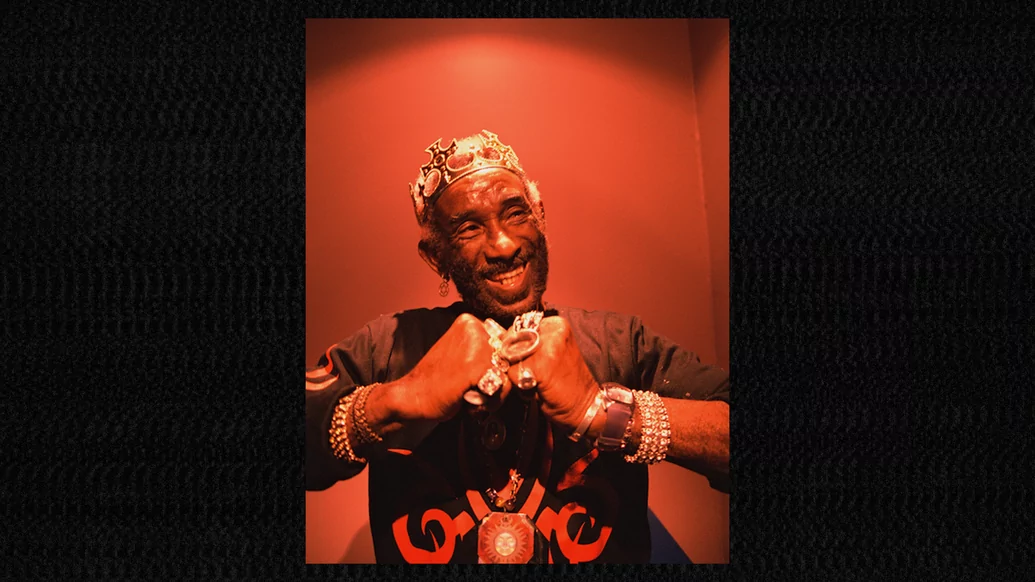

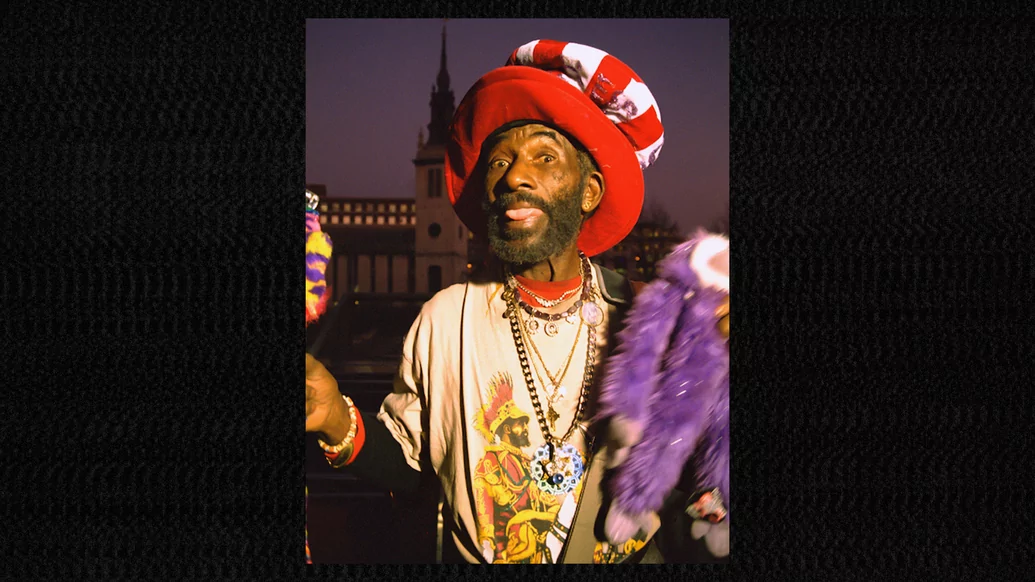

“Even people like Paul McCartney [were] in awe of him, Keith Richards was in awe. I always viewed Lee as the Dali of music, it was that kind of supposed ‘madness’. But Perry was never mad. He was just overstanding... In Jamaican street language a Rasta would say, ‘You overstand, you don’t understand you overstand.’ That was the thing with Perry, he overstood everything. He was way out there. So to some people he may have appeared to be crazy. I’ve been with him and he’s said, ‘Stone is my new God, Dennis.’

“I said, ‘What?’

“He said, ‘Yeah, stone. The energy you get in a stone.’

“So he’d be walking around with a stone. But when you think about it there is an energy in a stone. It’s like some people like to hug trees because they get energy from it. Perry would say that there’s an energy in everything. But you have to have that overstanding, or in English you say understanding, to realise the energy in these things. That sort of supposed ‘madness’ that Dali had made him able to create surreal pictures. And that’s the thing about Perry’s music — it’s quite surreal. When people look at a Dali picture, everybody has their own different view of it. It’s the same with Perry’s music, everyone sees a different meaning.

“I once saw him in Paris, he walked on stage with two baguettes, one in each hand, and announced, ‘Bonjour, Paris!’ That was Perry for you. The day before he passed away, he posted something from Jamaica. It was him on the beach. The next day, my wife came up to me and said, ‘Have you heard? Scratch died.’ I said, ‘No, no. I saw him on the beach yesterday.’ It just came out of the blue. It really shook me because he didn’t look ill or anything to me. There are certain people you just don’t ever think of them not being around, you know? Perry was one of those people. The energy those people have even though they pass is still here. It is preserved. That’s how powerful their magic is. They will be there with you until your time comes. And after that for the next generation and the generation after that.”