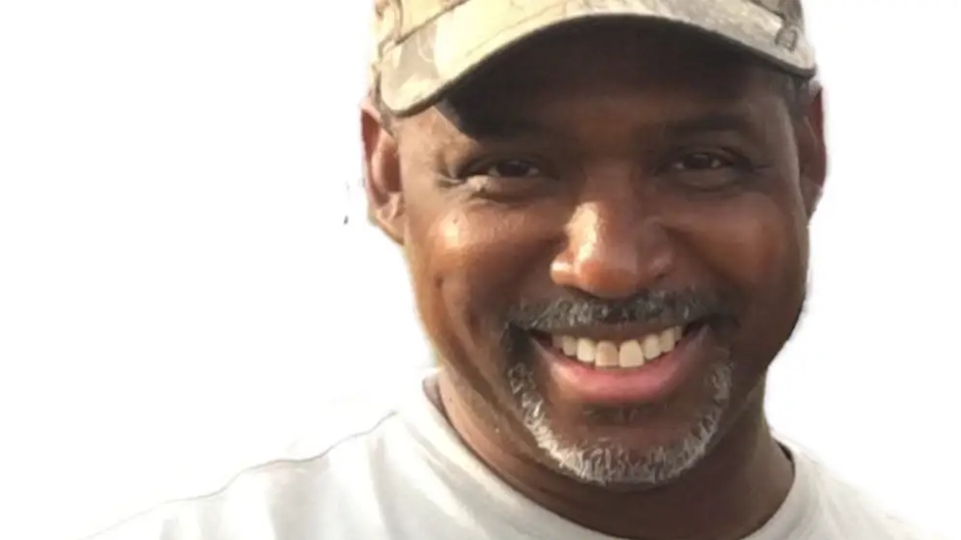

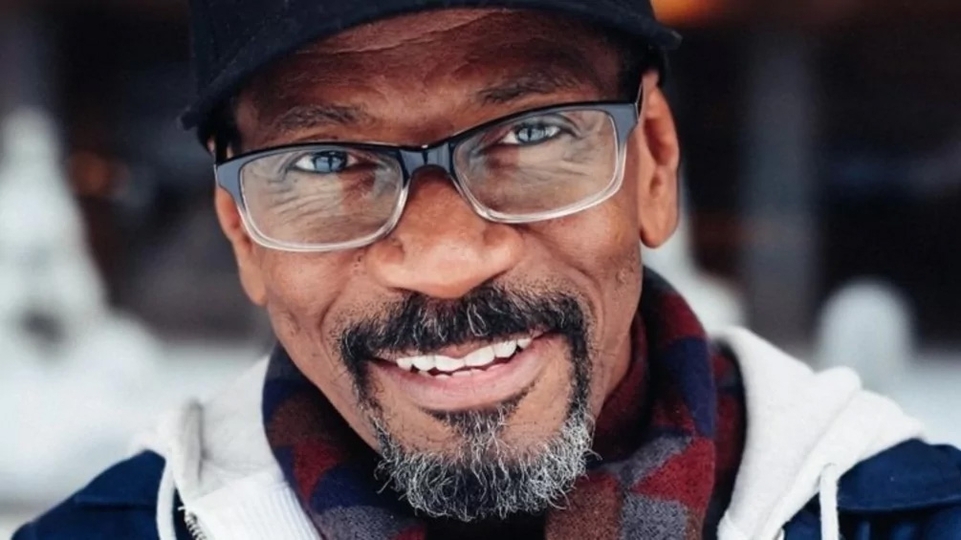

Marshall Jefferson: Master of the house

It’s true that house music would still exist if Marshall Jefferson hadn’t been around to guide it — but it’s equally correct to say that without Jefferson, its sound and its traditions would have evolved far differently. DJ Mag got together with the iconic artist to find out how house happened, and what’s in store for the future

Memories fade over time, and what memories remain become more and more shaded by personal experiences and personal interests. That helps to explain, in part, why the story of house music’s Chicago roots can feel so convoluted at times. All of the major players, at least those who still survive (R.I.P. Frankie Knuckles, et al.), have a slightly different tale to tell, often related with a self-aggrandising fervor — but Marshall Jefferson, one of the genre’s true pioneers, thinks he has a way to get the story straight once and for all.

Jefferson is speaking with DJ Mag over the phone from Manchester, UK. His voice is a welcoming, chilled-to-the-max drawl that’s instantly recognisable from his 1996 spoken-word track, ‘Mushrooms’.

“The original house masters are on Facebook all the time, arguing about who started what,” he says. “It’s like, ‘I did this first,’ ‘No, I did that first,’ that kind of thing,” he continues. “I’m figuring I’m going to get them all into a room and let them go at it and talk it out. We actually already have a tentative date set in April.”

If there’s anyone qualified to lead that pow-wow, it’s Jefferson. The Windy City native is one of the architects of house music — the man responsible for more of the genre’s elemental tracks than anyone else you’d care to name. His earliest releases, like 1985’s ‘Go Wild Rhythm Trax’ (released under his initial alias, Virgo) helped to shape the skeletal, primal sound of early house through its angular drum machine rhythms and sci-fi-on-a-budget vibe. Releases like 1986’s ‘7 Ways’ (as Hercules) added a touch of late-night sleaze to the house template.

Still others, such as 1986’s ‘The Jungle’ (produced by Jefferson and Harry Dennis as Jungle Wonz) and 1988’s ‘Open Our Eyes’ added layers of emotional resonance to the still-new house genre, and equal the work of acknowledged deep house masters like Larry Heard. Jefferson also played a major role in acid’s start, producing and mixing two of the style’s foundational cuts, Sleezy D’s ‘I’ve Lost Control’ and Phuture’s ‘Acid Tracks’, from 1986 and '87, respectively. He refined vocal house through his indelible production work for acts like Sterling Void & Paris Brightledge, CeCe Rogers, and Ten City. And that’s just scratching the surface of his massively influential early output.

GOTTA HAVE HOUSE MUSIC

But above them all, there towers one song: 1986’s ‘Move Your Body’. With its rollicking piano, chunky earworm of a threechord riff and the requisite thumping kick drum, the music itself is more than enough to get the dopamine flowing. But it’s the lyrics, sung by Jefferson’s then-coworker Curtis McClain with equal parts ecstasy and pleading, that seal the deal. The near-canonical text — “Gotta have house music all night long / with that house music you can’t go wrong / give me that house music, set me free / lost in house music is where I wanna be / it’s gonna set you free”— is part of clubland’s collective unconscious. It serves as a rallying cry to this day, as does the track’s “move your body, shake your body” chant.

But it’s Jefferson’s barrelhouse part that kicks the tune into gear, and at the time served as its most singular feature. ‘Move Your Body’ may have not been the first house song to feature a lead piano — that’s another bit of house history that’s up for debate — but few used it more effectively. Jefferson’s inspiration for using the piano as such a prominent feature of the tune is a bit surprising.

“Elton John, ‘Benny And The Jets’, man!” Jefferson exclaims. “Elton was a piano-playing fool in the ’70s — it was like straight out of a black Baptist church. He had so much soul, he was on Soul Train!” (It’s true — Elton John appeared on the show in 1975, banging out ‘Philadelphia Freedom’ on a Plexiglas piano.) “The reason I wanted to have a funky piano in ‘Move Your Body’ was because of Elton John.”

Just one problem — Jefferson couldn’t play the keyboards. His now-commonplace, then-inventive solution: “I recorded the piano at 40 beats per minute, and then sped it up to 120.” Born in September of 1959 — a Virgo, of course — Jefferson’s tastes in popular music as a kid growing up in Chicago were about as far away from club music as you can get.

“I was heavy into rock,” he admits. “I really loved Deep Purple, along with Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath... the heavy stuff.” By the ’80s, his tastes had begun to broaden, thanks in part to the radio show that nearly every Chicago house producer who came of age back then cites as an influence. “I was listening to the Hot Mix 5 on the radio, and they were playing a lot of European imports which were very nice,” he says with a bit of understatement.

SPIN TO WIN

It was a visit to one of Chicago’s hallowed dance clubs that started him down the path that he’s still traveling today. “As far as getting into house house, that happened because there was this girl at work named Veronica,” Jefferson, who was a postal employee at the time, recalls. “She was a former stripper — she had an awesome body, but would dress kind of strangely sometimes. I asked her, ‘Where you going looking like that?’ She said, ‘I go to the Music Box!’ I had no idea where that was, but I followed her there.” Ron Hardy, the club’s groundbreaking resident, who died in 1992, was at the controls. “And I got turned out! It was the loudest sound system I’d ever heard, and coming from a rock background, loud was right up my street.”

Jefferson and his friends from the post office had already been getting into spinning records — but playing at a club like the Music Box, or any club for that matter, wasn’t a viable option. “We were all working the graveyard shift at the post office, from midnight to 8:20am, so that wiped out our party hours,” Jefferson explains. “We’d mainly just be DJing in our basements, just making tapes for each other. Once in a while we would play a post office party, or our girls’ birthday parties or family things. But we’d still spend like 200 bucks a week on records to do that.”

The rules of house hadn’t yet been codified — the term basically referred to anything that filled the floors at clubs like the Music Box or the Warehouse. But it was the release of a track in early 1984, one considered by many to be the first real-deal house record, that began to both nail down the rules of house music and lead Jefferson into production. “I went to the record store and saw ‘JESSE SAUNDERS HOT HOT HOT.’ Jesse Saunders was a known DJ, and I was like, ‘What? Jesse Saunders on a record?’”

The track was ‘On And On,’ produced by Saunders and his fellow Chicago trailblazer Vince Lawrence in 1983, and released in early 1984 on Saunders’ Jes Say Records. It’s a primitive, lowbudget Space Invaders–tinged cut, full of frenetic handclaps, bouncing basslines, and a randomly swooshing synth.

“It was a very bad record,” Jefferson says. “If you listen to it now, well, it’s not really much. I thought, ‘Man, I could do better than this!’ That’s what started the whole thing. Every single house originator, including myself, would not have made a single record if it wasn’t for ‘On And On’. I’d still be working at the post office if it wasn’t for that record.”

GEARING UP

If Jefferson was going to outdo Saunders and Lawrence, he’d need some equipment. As it happened, soon after the release of ‘On And On’, one of Jefferson’s friends needed a lift to the local Guitar Center.

“I get there, and one of the salesmen is telling me, ‘I have this thing, a Yamaha QX1 — it’s a sequencer, which means you can be playing a keyboard like Stevie Wonder, even if you don’t know how to play at all.’ I was like, ‘Wow, how much is this thing?’ He goes, ‘Three grand.’ I tell him I don’t have that much. ‘Where do you work?’ I tell him the post office.”

In those days, the post office was a coveted, lifelong job, and the sales person offered Jefferson a $10,000 line of credit. “So I get that QX1, and I’m like ready to go. But he goes, ‘Wait, now you need a keyboard!’ I’m like, ‘Oh, yeah — you’re right!’ I get a Roland JX-8P. Then he says, ‘You know what? Now you need a drum machine!’” A TR-707 and TR-808, along with a recording mixer and a Tascam Porta-One multi-track recorder, were added to the pile. “And then he’s like, ‘This is what you really need — a TB-303. It’s only $150, and you can make basslines with it.’ I say, ‘Yeah, that’s what I want — basslines!’”

His line of credit exhausted but newly flush with hardware, Jefferson went to work. The result was an incredibly prolific period that resulted in a vitally important body of work, with bona fide classic followed by bona fide classic. His Discogs page lists 915 credits, most of them from the ’80s through the late ’90s — granted, a chunk of those credits are through multiple pressings, reissues and the like, but that’s still an amazing run that has few, if any, equals in the house realm.

If things slowed down on the production front after that fertile era, it was for a reason — Jefferson eventually decided to expend more of his energy on DJing, lured by its steadier stream of income. That, and an acute fear of flying, explains the fact that he moved to the U.K. in the 2000s. “I don’t really like long flights,” he says, “and 95% of my gigs are in Europe, so it made sense.” His aversion to jets, in a roundabout way, leads Jefferson to believe that he’s the one to thank (or blame, depending on your viewpoint) for high DJ fees. “People would be like, ‘We’ll give you $3,000 to come out here and play,’” he explains. “I’d say no, because I really didn’t want to fly. ‘We’ll give you $5,000.’ Still no. ‘$10,000!’ ‘Okay, where’s my ticket?’”

He had originally settled in London, later settling in Manchester. “In London, I was paying $3,500 a month for a studio; in Manchester, I pay $550 a month for four bedrooms and two bathrooms.”

Somewhat incongruously, Jefferson became buddies with his Manchester neighbor Mark E. Smith, the late founder and lead force behind the singular post-punk combo The Fall; Smith’s famously fearsome acerbity is something of a yin to Jefferson’s good-natured yang. “He was a nice contrast to me,” Jefferson admits, “He was a very... memorable person, let’s say. He was definitely opinionated. He would always come over and visit, but we didn’t really talk about music. He would bring a movie over and we’d just watch it. He knew I don’t drink or do drugs, but he would bring all this stuff over anyway for himself. He’d just relax, basically — it was cool.”

RETURN TO THE SOURCE

The past year has marked a turning point for Jefferson. He re-recorded the parts of ‘Move Your Body’, including a new vocal session from the original’s Curtis McLain, and handed them over to Mark Richards and James Eliot, the British house duo known as Solardo. The result was a jacked-up but still faithful version; released in October, the track has been a major club hit in the U.K. and beyond, and as of press time is making inroads in the U.S. Can he now play that piano part at full speed? “Oh, no, man,” he admits. “But now I don’t have to slow it down to 40 beats per minute. Now I can do it at 80!”

Apparently working on that new version began to get the creative juices flowing again. Less than a month later, Jefferson’s remix of Riton & Oliver Heldens’ chirpy, Yazoo-referencing ‘Turn Me On’ hit the digital shops. The new focus on music making led to a bit of soul searching and a major decision. “When I’m over there in Europe, I’m DJing nonstop,” he says. “It’s an endless circle. At some point I started thinking, ‘enough of that — I’m going to come back and start making records again.’ I was just itching to get back into production, to be making hot, underground stuff. I want to be back in the trenches.”

In early November, he moved back to the States — specifically, to Long Branch, New Jersey, about an hour-and-a-half drive south of N.Y.C. — in order to give the studio his full attention. Not that he’s giving up DJing entirely. The very day he flew back to the States, he played at midtown Manhattan’s Paradise Club, a glitzy disco owned by the onetime Studio 54 honcho Ian Schrager.

It wasn’t an ideal setting for Jefferson — the spot is lavishly deluxe, and the crowd that parties there tends to be on the upscale Euro end of the clubbing continuum. But a few heads did make it out, and Jefferson, ever the pro, got the crowd dancing with a playlist that boasted the kind of classics that are nearly Pavlovian in their effect; even the upper-crusters couldn’t resist.

At the gig, Jefferson was sporting an outfit that might best be described as pharaoh-goes-to-the-rave; it’s currently his favorite way to present himself when he spins. “I’m a priest for the church of underground house music, and these are my church robes,” he explains. “Inspired by the great chiefs of Mardi Gras and the prophet himself, Elton John. They help me capture the waves of positivity for my sermons.”

But when DJ Mag meets up with Jefferson at a downtown diner a few days later, he’s dressed a bit more casually: shortsleeved tee, rumpled slacks and a baseball cap. He’s in heaven as he digs into his order of turkey meatloaf. “Oh, my God,” he moans. “We sure don’t get this in England.”

He’s in story-telling mode — just like he is in his recent autobiography, Marshall Jefferson: Diary Of A DJ, written with Ian Snowball. Sitting at the diner, he relates the tale of one memorable late-’80s gig in New York City. He was performing ‘Move Your Body’ live at an East Village club called the World, where Frankie Knuckles, who had by this time repatriated to his native N.Y.C., was a resident.

“Prince was there that night, and I met him backstage. He shook my hand and said one word: ‘Purple.’” Jefferson pauses for effect. “I’m thinking, what the fuck? But apparently, Prince could see people’s auras, and mine was purple. The funny thing was, I was in a limo a year or so later, and the driver could apparently see auras, too. And he said ‘purple’ as well. He said that he had only met a few purples before in his life — and one was James Brown!”

Here’s another one: “I can remember when we were recording ‘Pleasure Control’ [credited to On The House], and Ron [Hardy] brought his heroin into the studio,” he says, shaking his head. “The engineer thought it was cocaine and did some. He ended up huddled in the corner, during this 14-hour session, going, ‘That was no damn coke, man! That was no damn coke!’ Me and Ron ended up having to engineer the session ourselves, in a 24-track studio. That was a real crash course in engineering!” Jefferson punctuates the story with a hearty, deep-voiced laugh. He’s told these anecdotes before, and he’ll tell them again, but he spins them with such gusto that you’re still in thrall.

Mostly, though, he wants to emphasize the newfound focus on his production activities. There’s a remake of Hercules’ ‘7 Ways’, featuring original vocalist Michael Smith. New music is on the way from Jefferson and CeCe Rogers. He’s back in the studio with Roy Davis Jr., who’d worked with Jefferson on such hugely affecting deep house cuts as ‘We Are Unity’, released in 1990 under the Umosia moniker. There’s an album on the way from Ten City. “And there are about 40 other projects that I need to catch up on,” he laughs. “I’ve never been this busy!”

CREATION CITATION

After three-and-a-half decades, it must be hard to keep the enthusiasm up and the energy flowing. “I think part of why I can still do this is that I haven’t had a drink or a drug since 1986,” Jefferson says. “But you know, there’s also the idea that every song I do might be the last one. I mean, I just turned 60, and so many of my friends are dropping like flies.”

One of those friends was his lifelong comrade Sleezy D, of ‘On And On’ fame. “He was just with me, helping me to promote my book,” Jefferson says, shaking his head. “He would dance from the first song to the last, always. He didn’t look sick at all — and then a month later, he’s dead from kidney failure.”

Losses like that can lead one’s thoughts to legacy, to what you’ll be leaving behind after you’re gone. “That’s why I’m working so much now,” he softly states. “You never know what’s going to happen, but I want to get it done before it does.”

But later in the conversation, he begins to realise that his legacy may be already set. “Man, there was some rapid-fire genre-starting at one point,” he says. “I don’t think acid house would exist if I didn’t produce ‘I’ve Lost Control’ and ‘Acid Tracks’. I put piano on ‘Move Your Body’ and that changed the whole sound of house music. And I helped to define vocal house with the Ten City and CeCe Rogers stuff. And that’s pretty good, I’d say.”

It’s more than pretty good. Jefferson’s just summed up how hugely consequential he’s been to house music’s rise, and how far his contributions have gone to shape the musical world we live in today. That’s a legacy that will last for generations to come — but first, Jefferson has a lot more work to do.