The rebirth of Todd Edwards

Todd Edwards is a house and garage veteran whose signature productions have lit up dancefloors for decades, and whose collaborations with Daft Punk sit in the record collections of millions. Yet Todd has battled crises of faith and self-worth throughout. This is the story of how he came back stronger

Every genre has a resident ‘“nice guy”, but it’s doubtful that they come nicer than Todd Edwards.

Todd has been an effervescent presence in dance music for nearly 30 years. His telltale production style, sample-heavy and delightfully swung, is a crucial element of US house, UK garage, and early dubstep. As if it wasn’t good enough being one of the foundational ‘Teachers’ listed by Daft Punk on their 1997 album ‘Homework’, Todd went on to become a close friend and serial collaborator of the Robots, too. But you don’t have to take their word for it. Earlier this year, Todd’s celebrated back catalogue was rescued from limbo and uploaded to streaming services for the very first time. Todd, everyone agrees, is deserving of his flowers. And now he’s getting them all over again.

Todd is at home in Los Angeles when we connect, flanked by two framed records commemorating his work with Daft Punk — gold for 2001 single ‘Face To Face’ and platinum for 2013 album ‘Random Access Memories’ — as well as a wall-mounted cross constructed of motivational quotes.

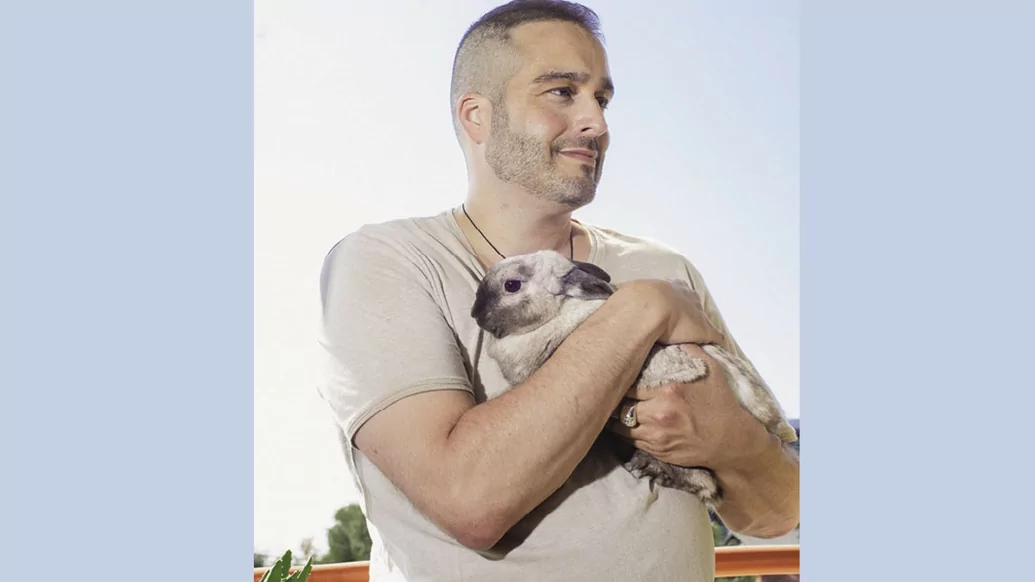

He is an endearingly hyperactive conversationalist who breathlessly sounds off on topics like fear-driven cable news or pre-chorus chord progressions for 20 minutes at a time, while simultaneously offering concessions to the alternative viewpoint. Every monologue is peppered with a cut-up chorus of Todds, all gabbing away at each other. “It’s so cathartic to be able to share my thoughts with you in a non-grumpy way,” he grins. “I try to keep the grump inside the apartment.” Any protective guard is swiftly broken once we mention the rabbit playing a starring role in Tonje Thilesen’s photography, sending Todd into a fit of giggles.

“I have two rabbits — the one who allows himself to be picked up is called Q-Tip. I’m very excited that Q-Tip is going to be famous,” he deadpans, composing himself. “Listen: I’m kind of an adult child. I don’t give a shit about my ‘brand’. I dress in T-shirts and pose with bunny rabbits for serious shoots, that’s me. I’m 48, dealing with 20-year-olds in the house industry. This keeps me young.”

Fragments Of Time

Todd Edward Imperatrice was born in 1972. The product of a sprawling Italian family from New Jersey – Hold the Sopranos jokes, he’s heard them all, and even worked in a burger joint across the road from where the show’s infamous final scene was shot — Todd found his Christian faith as a teenager. It’s unlikely the strong-willed conservatives within the patriarchal dynamic would have allowed him to deviate from this path anyway.

While developing a taste for electronic music as a young man, Todd’s proximity to the city of Newark meant the influence of Tony Humphries’ thumping sets at Club Zanzibar was never far, although at this point, Todd was too meek to become a clubber in earnest. The spark to start producing was provided by a friend, ‘Filthy’ Rich Crisco, who later laid down one of garage’s all-time great anthems, ‘I Refuse (What You Want)’, as part of short-lived trio Somore.

“Rich got me on the house tip by introducing elements at exactly the right time,” Todd recalls. “He was the first to play me Frankie Bones and Todd Terry, then Basement Jaxx later on. I’ll concede that I could stand to do more listening to what’s out there, but I really don’t need a lot of influence. My guiding instinct was to not stumble over lots of styles, but come up with a signature. When you hear a Masters At Work record, or a Todd Terry cut, or something by MK, it’s clearly them,” he continues. “I set out to make a sound for myself, so that when you drop a Todd Edwards record you know it’s by Todd Edwards.”

This premonition came to pass in unexpected ways. By 1995, Todd was pumping out records that were by turns soulful and skippy, tactile and robust — the kind of qualities which could keep saucer-eyed revellers locked in when they might have otherwise flagged and gone home. The Sunday afternoon UK garage scene was underway in South London boozers, as DJs like Grant Nelson, Matt ‘Jam’ Lamont and Dominic Spreadlove would use pitched-up records from both Todds to hold court with the junglists, who flooded in after Saturday all-nighters at neighbouring Ministry of Sound. When ravers of a certain vintage talk about ‘Back To 95’, this is what they get misty-eyed over.

Todd Edwards’ music has a rare transatlantic appeal — ruff enough to captivate diamond geezers in Elephant & Castle, but reverent enough to warm the cups of New Yorkers’ lollipop headphones. ‘Saved My Life’, released on seminal label FFRR in 1996, could charm expressive dancers at NYC house love-in Body & Soul, as well as those who would be bussing gunfingers to DJ Bigga G’s ‘Mind, Body & Soul’ down the line. Garage soon begat speed garage, with Todd’s remix of Sound Of One’s ‘As Am I’ a cornerstone of the spin-off sound. Before long, another strain had developed, as the chipped vocals and thick lashings of organ in Todd’s music helped propel 4x4 and bassline in the North.

Up until the 2010s, Todd would say yes to more or less every offer, resulting in a strikingly varied body of work. He’s surely the only producer to remix both TLC and LOL Boys, Spank Rock and Robin S, Klaxons and Kristine Blond. The effects of Todd’s prodigious early run continue to ricochet in intriguing ways.

Take Kristine Blond’s ‘Love Shy’: flipped by Todd, Tuff Jam and Jeremy Sylvester on a string of remixes in the late ’90s, ‘Love Shy’ was reworked a decade later by Platnum and propelled into bassline anthem status by a DJ Q remix. DJ Q was first turned onto garage and 2-step as a teenager in Huddersfield by his older brother’s collection, which included multiple records by a producer named — you guessed it — Todd Edwards. Todd is a binding element in the garage universe, a carbon atom traceable in nearly all living things.

Restless Soul

The material gains of being hard-coded in the DNA of a generational sound are less impressive than you’d think, Todd says. “Over time, I’ve come to understand that people singing my praises doesn’t always translate into prosperity. If you’re not in the epicentre of what’s going on, you can actually miss your own impact entirely.”

Unbeknownst to Todd until much later, one game-changing producer taking direct inspiration was Burial. In one of his only interviews, the dubstep enigma told Mark Fisher that “[Todd Edwards’] tunes can melt anyone” and cited the American’s celestial application of samples as a bedrock of his own work.

Contemporary allies like DJ Q, DJ EZ and Dance System — “one of the good guys,” notes Todd, whose “charisma and integrity” compelled a collaboration that will bear creative fruit this summer — continue to marvel at how fresh Todd’s micro-sampling sounds, even after nearly 30 years. “What I appreciate most about Todd’s work is the other-worldliness,” explains Dance System. “It’s like nothing else; the little chops and samples are not from this planet. It’s almost as if he has a beautiful alien orchestra!”

Todd’s enduring presence in each wave of house and garage — bigged up by Disclosure here, celebrated by Annie Mac there — means he is in a state of constant reintroduction, straddling an age-gap that only continues to widen. Appealing to young listeners while sticking to a winning formula is admittedly a challenge, sighs Todd.

“I’m trying to approach making music with a little bit of a scientific strategy these days. There are different spectrums: you have your sexual spectrum, you have your autistic spectrum, and I think music has a spectrum, too. On one side is that tribal, instinctual, adrenalised energy of hard EDM and thrash metal. And then you have the cerebral, spiritual side. I find myself somewhere in the middle.

“It’s very easy to bash the kids; to say that their palates have become monotonous and sterile, to get annoyed when you hear basic pop on the radio,” he says, “but what are you getting annoyed at: the music, or the fact this music is popular and you’re not making it? As best as possible, I try to understand how this generation hears music, and then learn to work within that range on the spectrum while still getting my message across and not losing integrity. If you don’t learn their language, don’t expect any communication to come your way, you know?”

“I learned so much from my first UK show: the interaction between the DJ, the MC and the crowd was like nothing I’d experienced in New York. As an American, it just sounded like a pep rally.”

Dancing For Heaven

If there’s one moment of telepathic audience communication almost every Todd devotee can picture with their eyes closed, it’s this: simply utter the words ‘Jesus Loves UK Garage’, and a rippling harp ushers in the dream sequence.

It’s New Year’s Day 2003. On the fringes of East London, history is being made. A full decade into his career, Todd Edwards is stepping up for his first club DJ set. The venue is Romford’s Time & Envy, the night is DJ EZ’s 4by4, and the jet-lagged Jersey boy is sweating with anticipation in a homemade black T-shirt proclaiming Christ’s affection for UKG. (Todd can’t estimate how many bootlegs are in circulation today.)

EZ slots his records away as Matt ‘Jam’ Lamont and Karl ‘Tuff Enuff’ Brown beam from the booth’s back wall. Todd is summoned and cues up a custom dubplate cut for the night. Around 1,200 tightly-packed fans surge forward to the sound of — wait, is that The Carpenters? Todd stands, eager but flummoxed, as people begin to cheer and shuffle to the muted intro for 45 seconds or so. Then the tune kicks in, and the venue goes absolutely doolally.

Everything was thankfully captured on camera and is constantly regurgitated by various music platforms on social media. It never fails to smash big numbers, a readymade honeypot of engagement. What goes through Todd’s mind when he watches the video back? “Seriously, that gig was special and the reaction makes me smile every time. I didn’t go on the internet in those days, so all I had to go off was one in-store appearance at [London venue] City Sounds in 2001, but it was only about 100 people, so I still didn’t have a quantifiable measure of success. Romford was crazy.”

“They cheered every song, including that preposterous intro, which was intended to show the crowd how my samples worked. I learned so much that night: the interaction between the DJ and the crowd was like nothing I’d experienced in New York. The MC was saying things and the crowd chanting back — as an American, it just sounded like a pep rally.”

During his set, this innocence resulted in one amusing misunderstanding. As the crowd demands a rewind, Todd flashes a confused glance back to the MC. Unsure what was being requested, he whiffs at the chance of a thunderous reload, instead merely hitting the stop button and watching the turntable power down. He grimaces at the mention. "Tuff Jam always joke about that.”

It’s compelling to imagine that night as Todd’s sermon on the mount, a canonical apotheosis which took his following to new heights. In fact, it bookmarked the end of Todd’s first popularity cycle. Work dried up and Todd was forced to move back in with his parents. “Everything went backwards in a flash, and I took it very badly. It was disheartening and emasculating. I lost hope — in myself, and in God.”

“I had no coping mechanisms for my depression back then; mental health wasn’t a topic in the industry. No-one talks about what it takes to generate a second wave of success once the first has gone.”

Saved My Life

Todd’s spiral to rock bottom makes for tough reading. At his worst, he was seriously considering suicide, seeing repeated visions of driving his car off a bridge while on the way to work.

“I’m going to talk about this candidly, in case it’s helpful for someone out there to understand what it feels like to go through all that jealousy, anger and insecurity,” he begins. “I had no coping mechanisms for my depression back then; mental health wasn’t a topic in the industry. No-one talks about what it takes to generate a second wave of success once the first has gone. You can even be Kanye West, and when you lose your throne for a moment you just can’t handle it. On a smaller level, I’m still tormented by streaming numbers. They go down and I wonder: ‘Am I bad now? Is this it? I make bad art?’

“My 20s sucked. I don’t remember much of the good times because my memory is clouded by depressive mood-swings. I was a workaholic, avoiding personal issues in my life by pushing until I burned out. I wanted to quit every five minutes, but then would get terrified that I wasn’t moving through the levels of my career fast enough.” When Todd’s momentum came to a skidding halt shortly after turning 30, all that internalised pressure exploded. “I had an existential crisis and turned to God, asking: ‘Why am I here? What do you want from me?’ I just couldn’t find happiness.”

Todd takes a breath. This is heavy weather, but it’s clear he’s been preparing to open up. “I had nothing in the bank and mounting credit card debt, so I took a job at Verizon. I was on great money but it was so miserable. The company was run like a boot camp in terms of strictness, and I would arrive at my desk nearly in tears most days.” His voice begins to wobble.

“Even with this stability, my prospects were still going in the wrong direction. My friends in Jersey were settling down and here I was, under my parents’ roof, really testing their patience, bless them. I pictured myself in a coffin at the end of my life, and pondered what I would regret more: if I never returned to music, or never had kids and grandkids surrounding me? And I felt music was the thing I cherished most. So at the height of the American recession, I quit my job and started again.”

Todd puts a great deal of his entrapment at the time down to mismanagement. He was told to keep his emotions buttoned when speaking to the press and suspects he was kept away from connecting with fans on the internet as a power play. A toxic cat-and-mouse game dragged on for most of the 2000s. “My first manager was a very negative reinforcement type of guy,” Todd states with barely-concealed anger bubbling to the surface. “For years, every time I released a new record, he would re-release one of my tracks. It was pure spite.”

Todd reached out to DJ EZ and Daft Punk’s then-manager, Pedro Winter, for help — not a bad support network to have. They were shocked that Todd owned none of his master recordings, and urged him to bite the bullet and buy back his catalogue as a point of priority. “It’s easy to see the manipulation now,” Todd says, “but I didn’t converse with people outside my bubble. I was too weak and scared to leave this situation. I was very loyal, a team player. And the thing that really sucked is that, up until this point, I never had a team rooting for me.”

Bookings returned as the 2010s dawned, relished by Todd with typically wholesome fervour. “I was so grateful for getting work again that I started to make tracks with the names of parties I was playing. I did a show in San Francisco called ICEE HOT, so I made a jingle of me saying the name. That’s where ‘I Want To Be In Fabric’ came from too. Let’s face it: England is my biggest audience. The least I could do was say thanks for paying my bills.

“I’m glad now I went through the struggle,” he continues, perking up. “It broke me, but it also broke the links to bad influences in my life. Without that miserable return to Jersey, I never would have had the confidence to move to Los Angeles.” When Todd arrived in the place he now calls home, he realised it wasn’t just a shitty manager causing him grief. He had laboured under the assumption that an ascetic lifestyle was the appropriate one, bound in fear of what might happen if he began expanding his horizons. Suddenly, there was no need for anguish anymore. He learned to enjoy a good time.

“I drank a load of tequila at [LA night] A Club Called Rhonda and woke up feeling great; like, ‘Oh! This is what fun feels like! This, I guess, is what happiness feels like’. I shook loose some of the more devout thinking I had — that making money was bad, or being expressive when DJing was unbecoming. My connection to God is stronger for it. The trauma receded. I really began existing as myself for the first time.”

Fly Away

2021-edition Todd is evidently in better mental and physical shape than before. He’s been enthused by the reception to springtime single ‘The Chant’ – the “15 to 20” new tracks he has ready to go – and is revving himself up to become a born-again DJ.

“I’ve been preparing myself for the road. It’s not well known, but I’m diabetic, so I need to watch out.” Todd points to the example of David Camacho, a Jersey house giant who worked closely with the likes of Bobby Konders and Paul ‘Trouble’ Anderson in the nascent 1980s house scene, but passed away in 2011 due to complications with diabetes. “We lost DJ Camacho, we lost Frankie Knuckles from kidney issues... I need to get serious about this. I’m kind of a fatalist, so I tell myself that if I live to 70, I’ve done alright, and then have a spell of yo-yo dieting. That’s a bad approach, and I know it.”

Todd’s roar back to prominence is in no small part down to his recent deal with dance music juggernaut Defected. With nearly 150 Todd classics issued to streaming, a separate career-spanning ‘House Masters’ compilation, an official release of that iconic Jesus Loves UK Garage shirt, and with more singles on the way, some have quibbled about Defected’s acquisition of brand Todd.

Todd rationalises this even-handedly: He needed a launch ramp to the next stage of his career, so the partnership is mutually beneficial. “In today’s market, it’s not just about making art. It’s about making art in a digitally efficient fashion, so you’re able to capitalise when you’re on a high. I didn’t want to come off a hiatus and feel like I’d messed up the timing again. Defected has a built-in audience of old and young music lovers, they’ve been very supportive — plus, you know, working with them helped me not go bankrupt in a pandemic.” Then, he winks, “and there’s still one thing I’ve not signed away yet.”

He’s talking about ‘Odyssey’. A 2006 love letter to God that slipped through the cracks, ‘Odyssey’ has gathered something amounting to cult classic status amongst in-the-know heads. The album shows a different side to Todd — multiple different sides, in fact, as each track features a different vocal impression. Todd huffed helium to sound like Björk and crooned like Michael McDonald for maximum yacht-pleasing effect. The production is crystalline and the lyrics have an unresolved melancholy to them, seeking salvation in song. As an artistic statement, there’s no real point of comparison anywhere in Todd’s oeuvre.

Todd has been chipping away at an improved version of ‘Odyssey’ for close to a decade, and come 2022, there will be an accompanying (re)making-of documentary by filmmaker Billie JD Porter. The new version is, Porter says, “basically a different album by this point. It’s a fresh, loud take on the original. Old school Todd fans are going to be overjoyed when this record hits.” Todd reflects the enthusiasm here: “Billie is brilliant, and this documentary will really be the icing on the cake, delving into some deep topics I’ve never spoken about before.”

"The call back from Daft Punk was one of the biggest honours of my life. I can boast that I’m one of the few people who worked with the Robots on two different albums. I see Thomas and Guy-Man as brothers, but I also put them on a pedestal — and it’s hard not to, because they really are geniuses.”

As I Am

As much as he’s excited for the future, Todd can also seem deeply fixated on the past — perhaps even tortured by it. The tendency towards Catholic self-flagellation maintains. ‘Odyssey’ is the first ghost Todd is hoping to excise. The second, paradoxically, came after one of the greatest nights of his life. He brings it up surprisingly frequently on radio and in podcasts, and does so to us too, completely unforced.

“Timing is so important, but unfortunately the timing of things doesn’t necessarily work out the way you want. And I missed my moment after ‘Random Access Memories’. Let’s just say I needed some ‘me time’ when I got to LA. I was unready to be creative, and missed the boat with reissuing my catalogue,” he says while shifting in his seat, still evidently chewed up about this.

Everyone struggles to catch the wind perfectly in their sails, though, and hindsight is human nature. Being part of a genuine monocultural cultural force sounds like a net positive, right? “The call back from Daft Punk was one of the biggest honours of my life. I can boast that I’m one of the few people who worked with the Robots on two different albums. I see Thomas and Guy-Man as brothers, but I also put them on a pedestal — and it’s hard not to, because they really are geniuses.

“From a public standpoint,” he continues, warming up to the memory, “becoming a Grammy Award winner was a moment of vindication: a moment to disprove all the old-school conservative Jersey guys who asked why my father let his adult son live at home, blasting kick-drums in the basement; a moment where I got given the equivalent to the key to the city of Bloomfield, and my mother was able to go up there and collect it.”

Although, he laughs, a mix-up nearly turned his crowning glory into an anecdote he never would have lived down. “Thomas had told all the collaborators, ‘Look, if they call us up there to the stage, you’re only going to have a minute to walk on’. So my second manager and I hurried to queue up behind the cameras. We couldn’t see the stage, and didn’t realise Macklemore was performing ‘Same Love’ with a priest officiating these couples on stage. Only when we started getting applauded by the audience members did I realise I was standing in the wrong line!”

He clutches his face in mock-exaggeration at the thought of getting accidentally married on live TV in front of 28 million Americans. “Can you imagine what my Catholic mother would have thought?” Bang on cue, the phone rings: it's Todd’s mom, her ears somehow burning 3,000 miles away. Todd pops her on speakerphone and quickly pivots to another topic.

Positives and negatives forever jostle in Todd's mind, like an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other. He still needs validation, with twinges of regret nipping at the heels of his success. But this is what makes him a relatable and emotionally resonant figure in an industry that too often prioritises mechanically soldiering on as a virtue. Rather than trying to gloss over an unsatisfactory narrative, learning to value life’s imperfections has given Todd Edwards enduring appeal beyond most.

“I know what it’s like to have bottomed out,” Todd wraps up after a conversation that has breezily rolled on for an entire evening. “But then, I’ve been rescued, and that’s something to be thankful for. I’m just some guy from Jersey, yet I’ve been treated like royalty. Some things I’ve done at different points in time have branched out and reached millions of people. You want to make a difference when you’re on this earth — if I retired tomorrow, could I say that I had an impact?”

Todd answers this with a smile. It seems he has learned to rewind after all.