Castlemorton 1992: photographing the illegal rave that changed UK dance music forever

2022 marks the 30th anniversary of the biggest and the most infamous illegal rave that ever took place: Castlemorton – a week-long, 20,000-person party deemed so anarchistic that it shook Middle England to its core. Here, photographer Alan Lodge tells his story of capturing a week changed UK dance music forever

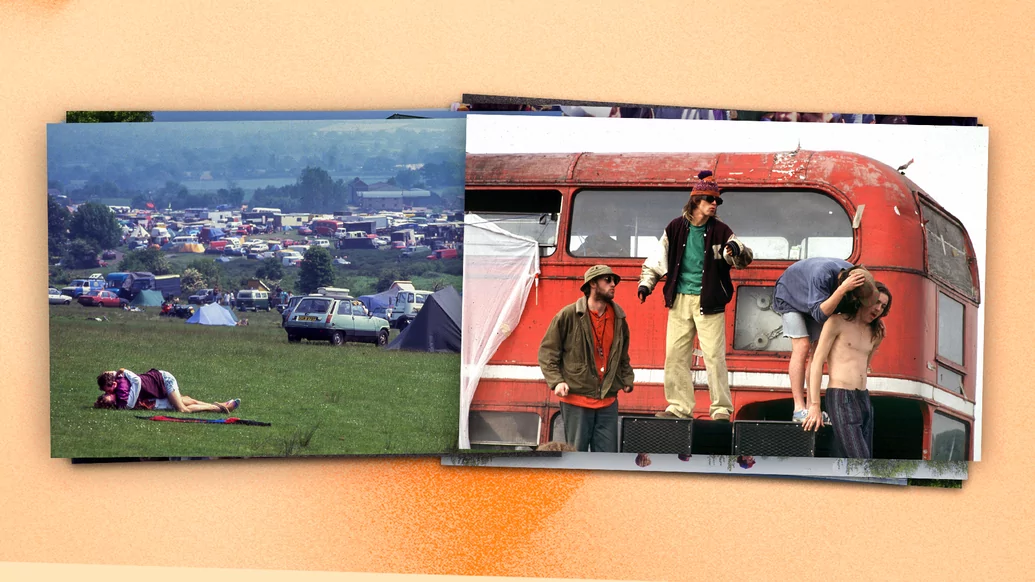

It started on a particularly sunny bank holiday weekend, on the 22nd May 1992. A ramshackle convoy of vehicles, which served as the rag-tag homes of a contingent of peaceful New Age travellers, snaked through Gloucestershire. In the summer, this nomadic community journeyed from DIY festival to DIY festival. But they’d just been refused entry to a site they had planned to use for their annual Avon free festival — a small event for around 400 people which they’d run successfully for a few years.

Having not only been socially marginalised but also brutalised in the most barbaric fashion by Margaret Thatcher’s police force in the past (see: The Battle of the Beanfield), the travellers moved on. They were also moved on by the police in the next county. Eventually they all ended up on Castlemorton Common: where the week-long, now almost mythical, party started.

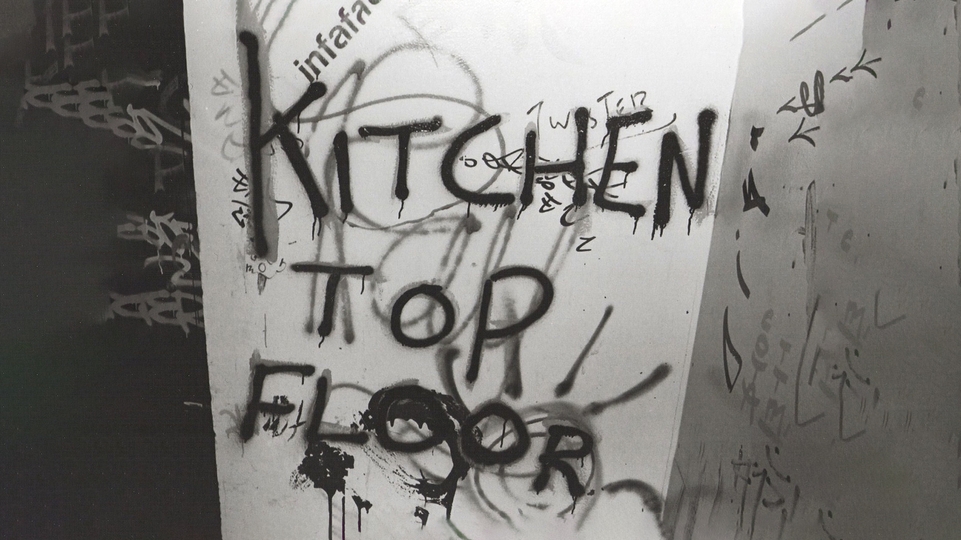

The sun beamed down and word about a free festival began to spread like wildfire. Acid house was still in its honeymoon period and the ravers began to rally their troops. Collectives like Spiral Tribe, the DiY Sound System, Bedlam, Armageddon and Circus Warp arrived and set up rigs on the common. An answer machine was set up: “Right, listen up revellers. It's happening now and for the rest of the weekend, so get yourself out of the house and on to Castlemorton Common... Be there, all weekend, hardcore."

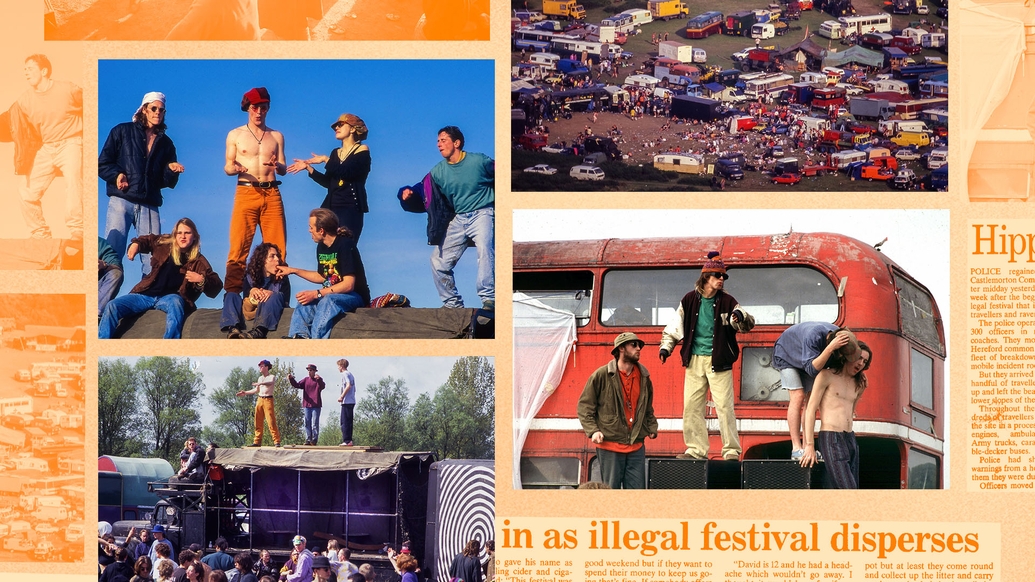

As the site began to swell, the press arrived. It had all the elements of a great story — hippies vs the establishment, a new youth movement thrown in, people with funny ideas about society, and drugs! The press jumped on the story like a pack of filthy hyenas descending upon a rotting piece of meat. James Dalrymple of The Times wrote that the people converging on the common “had established a mini-city with full catering facilities, a large-scale drug distribution system and their own internal police force”. It was also reported in the press at the time that ravers shot flares at a police helicopter, and that there were rumours that others cooked and ate a horse that had been injured by one of the lorries. No evidence was produced to back either of these reports up. The reportage inadvertently served a dual purpose: It ignited a moral panic (that was part of the plan as it sells papers) but it also served as an extraordinary advertisement for the event resulting in an estimated 20,000 people attending.

The implications of this week-long free festival still persist to this day: it resulted in the introduction of the infamous Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, a carefully-worded piece of legislation designed to obliterate acid house culture. In section 63(1)(b), it outlawed people gathering listening to music “predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”. Unlicensed raves were banned forever.

Photographer Alan Lodge, now 68 years old, was a traveller there that week. Having left his career as a paramedic in the 1970s, he’d dropped out of conventional society and taken to life on the road — often using his camera to document the horrific abuse his fellow travellers received at the hands of the police. Eventually, this was expanded to also documenting the culture, lifestyle and tribal identity of the New Age and acid house subcultures. He recently spoke to DJ Mag about his life at the time and that wild week 30 years ago.

Just Follow the Vehicle in Front

“Some people are constrained by the fact that they have to go to work. But we didn’t have that — we did things differently. We did a clockwise festival circuit around the country: the main bank holiday was the Avon free festival, then the Stonehenge [Summer Solstice] festival, then the August bank holiday. We didn't have to advertise events with this circuit; people basically knew what particular area of the country we’d be in and when. There weren't any mobile phones or computers or anything like that — it was word of mouth at first.

“With Castlemorton, there was a large number of people already in the area expecting the Avon free festival. People bumped into each other in lay-bys and the convoy started getting bigger and bigger. We ended up in Gloucestershire and the police said 'keep going, just keep going'. Police at the time didn’t really focus on stopping anything. It was more about removing a problem from their area of responsibility. That’s why we loved to put festivals near the edge of county boundaries — it created confusion about whose responsibility it was.

“I joined a convoy on the A46 with a bunch of travelling mates. We saw some other vehicles in a lay-by, asked them where they were going, joined them, went down the road a bit more and did the same thing again. You end up with a big convoy — just follow the vehicle in front. We ended up on the common. There we were. The numbers were already in the area, they didn’t have to come from around the country. And so when the site got seized, it was easily taken by force of numbers which is basically the only way you can do it if police object to you taking the land, which of course they’re bound to do.”

The Biggest Rave Promoter That Week Was the BBC

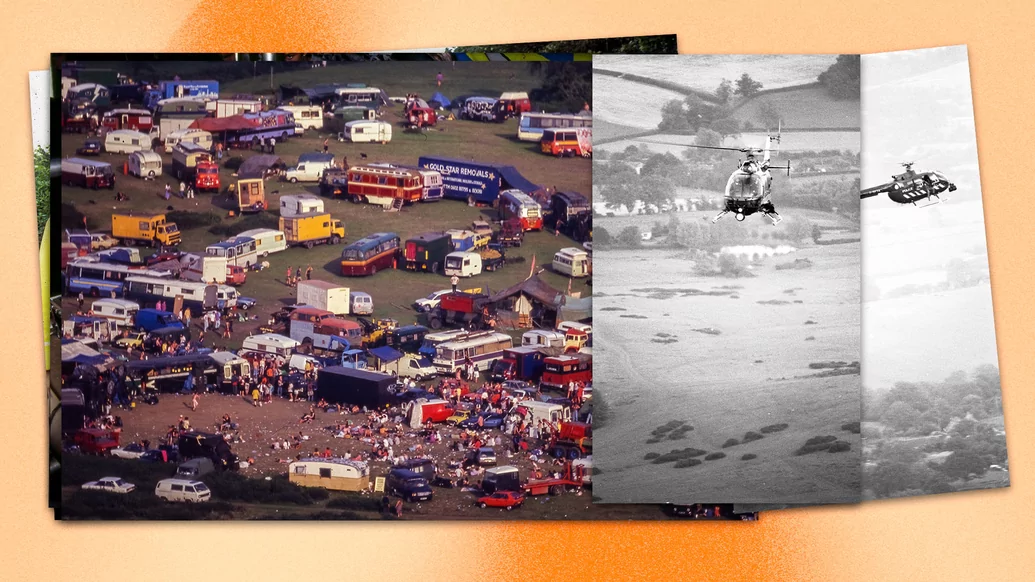

“People were glad to be able to gather for the first time in those numbers for a while. Some people and a dog arrived on the site, followed by 10 more, then 28 and so on. Then people kept arriving through the night and into the following day. Once it was above critical mass [too many people for the police to intervene through fear of starting a riot], it was too hard for police to think they could oppose it. And once the media, including the BBC, advertised it with their news stories, there were thousands turning up. With those numbers, if the police tried to stop people arriving they would end up with lots of other sites. So I think their reasoning was to contain it in one place.

“There was a Spiral Tribe rig, Bedlam Sound System had a rig and there was a whole DiY section. It was a bit of a musical journey actually: I’d go to one rig and listen, take some photographs, and then go to another one. I discovered that by wandering around the site you could create your own mix. The music was coming from one direction and I’d moved slightly to the left and I could catch a different arrangement.”

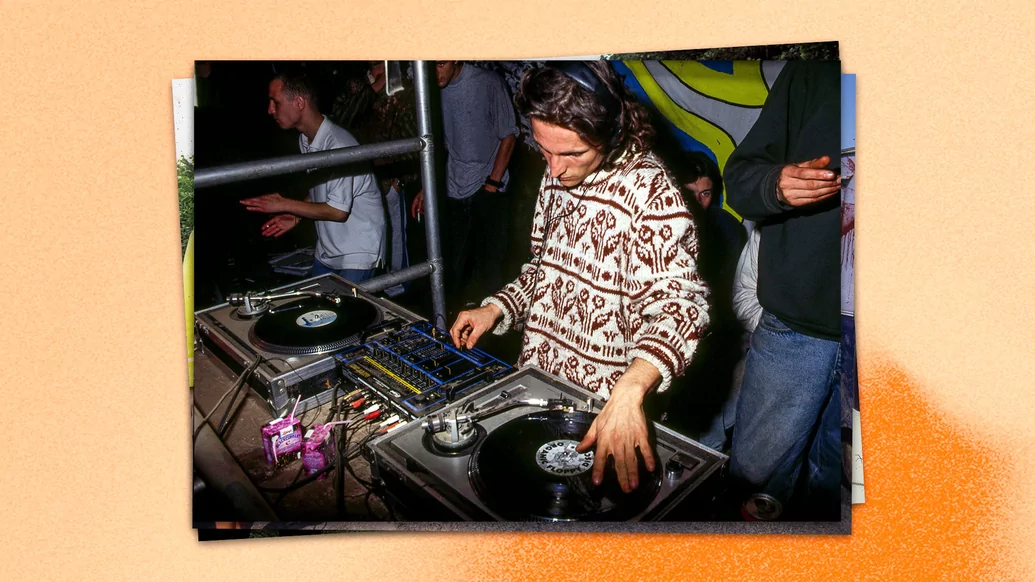

The Late Pete Birch On the Decks

“That’s Pete Birch [AKA Pete Woosh], one half of [the DJ duo] Digs & Woosh. He passed away in 2020. He was a founding member of Nottigham’s DiY Collective who were part-travellers, part-young ravers and part... whatever else. They were a diverse bunch. Electronic dance music had been big for about two or three years by then. I first came across it at a place called Treworgey free festival in 1989 in Cornwall. The usual traditional rock bands and people playing accordions or fiddles around fires was going on, but suddenly there was some very strange music coming from another hillside. I went and had a look. That’s when I first saw the intersection between the travellers and the ravers.”

“We Waved at Each Other and He Flew Off”

“Castlemorton Common is at the base of the Malvern Hills, it’s this famous musical landscape historically walked by Sir Edward Elgar [an English composer who lived from 1857 to 1934]. His first symphony is said to be inspired by that area because he was born around the corner from there. I went into the adjacent field, climbed the hill and looked at the site. I happened to have a large lens with me so I could take some decent landscape shots of the event. And to people's amazement, I managed to take photos of the police helicopter — we were at the same level. Generally you have to look up at these people, but we were at the same altitude. We waved at each other and he flew off.

“After the original Public Order Act [1986] we could no longer ‘bring vehicles onto a piece of land with the purpose of residing there’. But what if we didn’t reside there? What if we stayed up all night and made a racket? I believe that, plus the particular musical taste, is why a lot of this happened. It was a way of getting around the law; so the gathering could still take place, but it wouldn't fall foul of the original Public Order Act.”

“If You Can Be Comfortable in a Field, You Don’t Have to Go Home at the End of the Night”

“You can only speculate as to what was on the end of that finger, can’t you? That was on top of one of the rigs. There was a high proportion of young people that weren’t used to anything other than staying up overnight and going home. So that’s exactly what happened: a big group came, had it large, then went home. But then another wave came. So it’s not possible to say how many were there.

"There were different waves at different times. But the travelling community arrived at the beginning and stayed right to the end to clean it up. They were eventually evicted by high court order. Many folk coming into that scene didn’t have the capacity to be comfortable in a field. That’s what travellers knew how to do. If you can be comfortable in a field, then you don't have to go home at the end of the night, do you?”

“It Had Already Reached Critical Mass”

“The first day or two was a relief to some extent — we’d made it. But there was a growing cloud among some who were thinking ‘this isn’t what we intended and I wonder what the reaction to them out there [outside the festival] is going to be? So I listen to a few news reports on the car radio. Then I went on sentry duty a few times down the road to see the arrival of the troops. But it never came — it had already reached critical mass. I felt anxious. I shouldn’t have felt anxious because there were so many people having such a nice time around me. But, having some experience with that sort of thing before [at the infamous Beanfield incident] I did. But I managed to relax then and have a nice couple of days.”

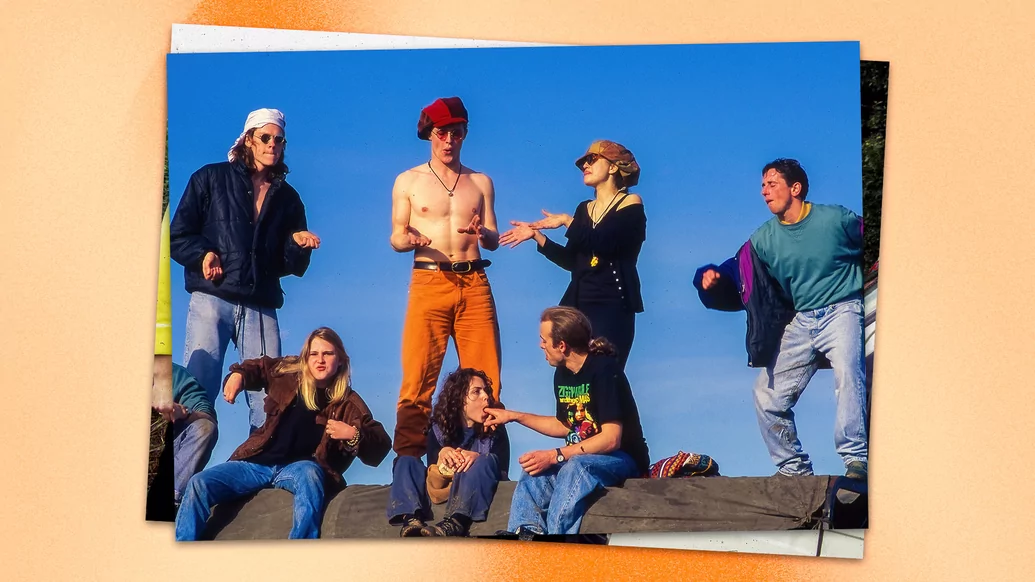

Multiple Tribes Together

“As older hippy types, we were a bit taken aback by all this because none of it was intended. Part of it was purely terrific for a festival but other parts weren’t. It was out of proportion to the size of what we generally had at this sort of event, we had multiple tribes gathered together. I was unimpressed by some aspects, there was no welfare or medical provision, none.

“There was such a rush to get there that it didn’t grow organically. In the end, there were some young people that were shitting in the woods, entering the local resident’s gardens and even sawing down live trees! Some of the travellers were really crushed by that. They felt that none of the things that they’d learned for 20 or 30 years about respecting the land was being taken into account. To them, it was a complete fucking disaster. But for many [in the raver contingent], they had the time of their lives with this freedom that they suddenly enjoyed in a tribal setting. A moment when ‘them lot out there’ [the authorities propping up the norms and values of mainstream society] actually couldn’t tell them what to do.”

Alan’s work is currently being exhibited at the ‘Radical Landscapes’ exhibition at Tate Liverpool, click here to learn more. At the end of May 2022, he will be at Lost Horizons in Bristol exhibiting his work and talking to support the release of a film titled Free Party: A Retrospective, click here to learn more about that.