The history of Spiral Tribe, the UK’s most notorious travelling sound system

Spiral Tribe were ‘90s Britain’s hardest hardcore techno crew – a travelling party troupe of anti-authoritarian acid-adventurers, and a scourge of the establishment. With co-founder Mark Harrison in the midst of writing a book on their story, and PRSPCT Recordings recently releasing a collection of classic cuts from live Tribe duo R-Zac, Harold Heath dives into their history, legacy and vow to 'Never Stop'

In the 1970s, a teenage Mark Harrison and his younger brother would hitch-hike to free festivals, the country-wide network of large-scale, outdoor music events which were, by their nature, adjacent to alternative politics. Psychedelic rockers Hawkwind always impressed Harrison, who recalls them setting up their own stage and sound system to deliver a “sort of psychedelic, but electronic and distorted sound — which was very dancey.”

Mark got the same thrill hearing Hendrix’s distorted guitar via pirate radio, gaining a sense of what treasures lay just outside the mainstream: illegal signals, buccaneer broadcasters and electronics pushed beyond their limits to open up new avenues of musical expression. In this combination of free festivals, anti-establishment politics, aversion to commerce and attraction to cultural outliers are the roots of Spiral Tribe.

Their days of living together as a travelling sound system over, DJ Mag speaks to each Triber at home via Zoom. Harrison is a graphic artist, loves playing with words and images, and is passionate about communication. He’s amiable and engaged, giving intense, lengthy answers to the simplest of questions, as though the questions themselves contain previously hidden layers and unfurling sub-sections of expanding ideas.

In the late ’80s, he was squatting around the corner from the Hacienda in Manchester at that key moment when UK dance music erupted: “Acid house didn’t exist, ecstasy didn’t exist, and then one Wednesday or Thursday down the Hacienda I was just standing there waiting for something interesting to happen and it just all kicked off. Something just aligned and we suddenly had all this fantastic new music, this fantastic new level of experience through ecstasy — and everyone was just completely blown away.”

Improvising electronic musician Sebastian Vaughan joined Spiral Tribe after their infamous ’91 New Year’s party at Camden’s then-abandoned Roundhouse. Like Harrison, he’s generous with his time, languidly delivering comprehensive answers that dance around the subject with plenty of intriguing asides, but always coming back to the power of music. Also, like Harrison, Vaughan went through a similar “very life-changing, cosmic experience”, arriving at Shoom’s darker, harder contemporary Clink Street one Saturday night in late ’89 and becoming an instant acid house convert.

"The rave scene seemed to be oscillating towards paid parties and clubs again, and we just said: ‘No way! It’s got to be in a warehouse, it’s got to be dirty, it’s got to be illegal and it’s got to be faceless’.” - Sebastian Vaughan

At the start of the ’90s, Harrison and Vaughan were living in the same Hampstead squat community, often bumping into each other at raves, but 1990 was the year the Tory government began seriously mobilising against illegal events. “There was this huge new movement, where the free festivals got electronic music,” says Mark, “this great sense that something epic was coming. Then you had this huge spike in psychedelics, which was obviously ecstasy-fuelled, creating this great coming together... and then Thatcher and her ilk oppressed all that.”

He’s referring to Tory MP Graham Bright’s acid house-targeted 1990 Entertainments (Increased Penalties) Bill, which raised fines for unlicensed parties from £2,000 to £20,000 with the possibility of six months inside for organisers. “A lot of the illegal warehouse parties got shut down, the rave scene seemed to be oscillating towards paid parties and clubs again,” says Vaughan, “and we just said: ‘No way! It’s got to be in a warehouse, it’s got to be dirty, it’s got to be illegal and it’s got to be faceless’.”

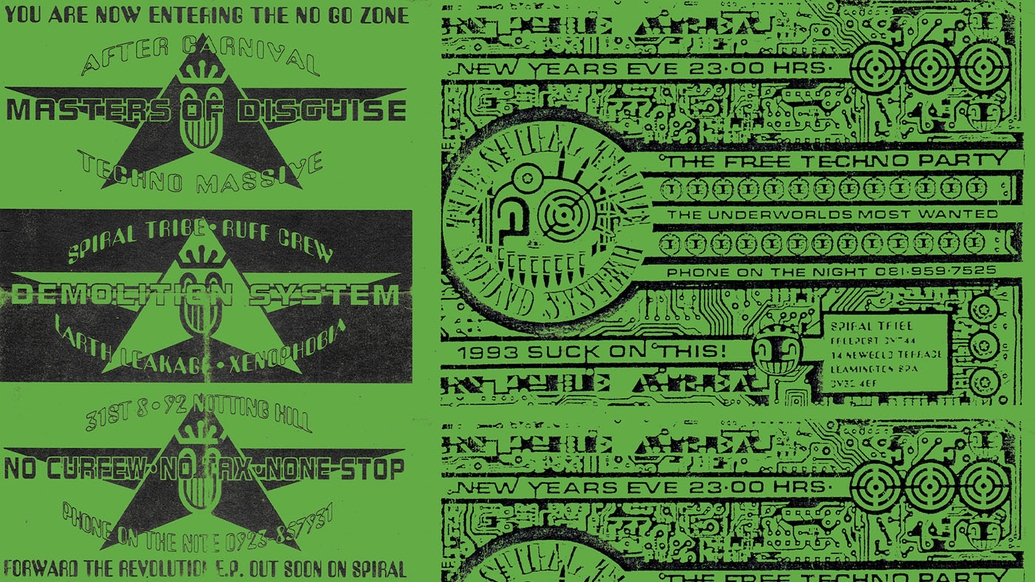

In late 1990, Mark, his brother Alexander, and friends Debbie Griffith and Simone Feeney hired some sound equipment and put on a pair of squat parties in North London called De-tension at the Skool House, “the first where we as a group used the name Spiral Tribe and identified as a collective,” says Mark. By spring of the following year, they’d bought their own soundsystem, and Harrison can pinpoint the exact moment when they discovered their mission: the Longstock free festival in Hampshire, summer ’91. The tribe rolled up with their four-and-a-half-kilowatt rig, rocked it till the very end, and then simply never went home again. “We realised as the solstice dawn came,” Mark says, “that we weren’t going home. We were nomads from that moment.”

They set off on the UK free festival circuit, spreading the acid house message to the UK free festival scene and provincial ravers. They played the music of the people — techno and hardcore — and always for free. “Spiral Tribe was not about making personal money,” says Vaughan, “it was all about just doing it. Whenever money came in, it was everybody’s.”

The Tribe vibe was full-on, 24 hours a day, relentless, never stopping. ‘Make some fucking noise’ was their official mantra, but it could equally have been ‘Never Stop’. Local DJs were allowed to play at their parties, which was just another aspect of their egalitarian ethos: “We really saw ourselves as the people’s soundsystem,” says Mark. Although the relationship between the ravers and the older so-called ‘new age’ travellers was sometimes fraught, Spiral Tribe forged a brief but beautiful underground alliance between the two that would reach its height at Castlemorton.

Now acknowledged as the UK’s biggest illegal rave, sound systems including Spiral Tribe, DiY, Bedlam, Adrenaline and Circus Warp congregated in Malvern in Worcestershire in May ’92 and created a temporary mini rave-town purely for hedonistic purposes, entirely beyond the control of the authorities. An organic, unorganised, five-day sun-rinsed party for an estimated 20-to- 50,000 attendees.

The press coverage was like a series of peak-time adverts for the joy of raves, but the authorities were ramping up their counter-rave activities and there was a sense that they were never going to allow anything like Castlemorton to happen again. Just a few weeks before, riot police — described by Harrison as “Men in Black with no numbers, the super violent right-wing hit squad of the police” — broke up a Spiral Tribe rave in Acton, smashing their sound system. “It was brutal, with a siege that lasted two-and-a-half hours. Many people were beaten by the cops,” he recalls. Following Castlemorton, many of the Tribe were arrested, their vehicles and sound system impounded and soon, the term ‘rave’ would be enshrined in UK law in 1994’s Criminal Justice Act.

It’s likely that some of the records being played at Castlemorton were made by Simon Carter, who had also been there as a punter. Carter was part of Earth Leakage Trip who’d put out tunes on Rising High and had the first release on Moving Shadow, their ‘Psychotropic’ EP, which included rave classic ‘No Idea’. Carter, who now also works as a music teacher and sound designer, has a substantial back catalogue under various names but is perhaps best known as Crystal Distortion and as one-half of the Spiral Tribe Liveset, which became R-Zac. He was about to become a crucial part of the Spiral Tribe tale.

With their reputation growing following Castlemorton, Spiral Tribe were given a break by producer/musician Youth, who gave them the run of his Brixton studio. The Tribe then signed a record deal with Big Life Records, which came with a tasty advance. They elected to spend it building a mobile studio, but needed someone with studio skills to help: enter Simon Carter.

Carter is a bundle of energy over Zoom, quick to descend into hacking laughter; direct, self-effacing, and full of funny tales. “I remember them knocking at the door of my squat and they were like, ‘Get in the van, we need to ask you something’. They had fifteen grand to spend on studio equipment and said, ‘You’re the only one that knows anything about how any of this works. So you’re gonna come up here, you’re gonna fucking choose it, and you’re gonna stick around with us until we know how to use it — and even longer if you want’. I was like ‘Wahey!’, grabbed my bag, said goodbye to everybody, and the next thing you know I was sleeping in the basement in the studio.”

They then kitted out an old trailer with studio equipment, which became their legendary mobile studio, Studio 23, with resident producers Crystal Distortion and 69db at the helm. The pair also decided that aside from making records they wanted to improvise live electronic music, and around ’92 started playing as the Spiral Tribe Liveset.

Meanwhile, the UK authorities were attempting to hold Spiral Tribe personally responsible for the organisation of Castlemorton by charging them with conspiracy to cause a public nuisance. The trial would eventually collapse in 1994 with all Spirals acquitted, but at the time, under extreme pressure from the authorities and the police, the Tribe simply drove their mobile studio and convoy of converted military vehicles out of the country.

“We stayed up late, life was a fucking game. Obviously it was deadly serious but also, we just had this energy, this power on our side and as long as we were true to it, we would get away with blue murder.” - Simon Carter

They began their exile in Paris and in summer ’93 put on the first Teknival — the name coined by Debbie Spiral — in Beauvais, France. “It is still,” Sebastian remembers fondly, “the biggest example of illegal soundsystem activity in Europe, if not the world.”

That kickstarted the blossoming of huge, free, illegal Teknival raves across Western and Eastern Europe. Later that year, Spiral Tribe relocated to Potsdamer Platz, which was then a patch of wasteland in the middle of Berlin. Not wanting to sully the Spiral name with commercial attention, Vaughan and Carter rechristened themselves R-Zac. Here they developed a stripped-back, pitched-up distillation of Chicago jack, Detroit groove and European ‘hardness’, with their signature production trick of adding a little delay on the kick to create their distinctive rolling sound. The music on the recent ‘Trailer Trax’ release on PRSPCT Recordings is from this time, capturing the raw energy of R-Zac when they began creating what would become the hard tec sound.

Both Vaughan and Carter talk about wanting the freedom to play at a tempo that felt good, which at the time often meant DJing 33rpm Chicago dubs and B-sides at minus 8 and 45rpm to get them to the 150/160bpm range they wanted. At that pace, in the heat of the rave, R-Zac fearlessly improvised for hours on end, forging their new sound in the moment, capturing inspiration live. “It was just instantaneous,” Carter tells us. “If you didn’t catch it, it was gone, you wouldn’t get it back. That’s what I really liked about it — the immediacy.”

Nearly two decades on, the music has lost none of that immediacy and is every bit as intense and uncompromising as it was. “Well, we were definitely quite boisterous and rude at the time,” recalls Carter with a smirk. “We stayed up late, life was a fucking game. Obviously it was deadly serious but also, we just had this energy, this power on our side and as long as we were true to it, we would get away with blue murder.” True to what, DJ Mag wonders? “Just keeping it on as long as possible. Never switching it off. Never stop.”

Both Carter and Vaughan mention the ‘never stop’ mantra, Carter with clear glee, Vaughan speaking of it as, if not a sacrament, then at least a duty. ‘Never stop’ sounds like a simplistic idea, but perhaps there’s more to it. ‘Never stop’ is a commitment to the power of the ever-lasting loop, the primal, tribal beat, the never-resolving pulse of funk, disco, house and techno. And when enough people commit to it, you can create singular moments like Castlemorton, where the dormant power of the people is unleashed — where we, and not the authorities, decide when to turn it off.

Spiral Tribe’s next move was to launch their Network 23 label in 1994, releasing 37 records over a two-year period and creating the hard tec and tribe techno blueprint, a sound which would dominate the Teknival scene for the next decade. They quickly developed a grassroots, independent operation, where, Mark recalls, “You could very easily make enough money to pay all the artists so that you would then empower other people to get studio equipment and sound systems.” Driven by their desire to be autonomous of larger commercial forces, Spiral Tribe were like a vinyl workers collective, initially running their label from the back of a D-series Mercedes van. Like all Tribe endeavours, it wasn’t for profit; it was making and releasing music purely for the love, with the added bonus that it inspired and supported the scene.

In the second half of the ’90s, Vaughan and Carter began to work with fledging Paris techno label Expressillon, a fruitful relationship that resulted in a steady stream of quality improvised dub, techno and hard tec. Harrison, meanwhile, launched his Stormcore label in ’96, pursuing a more experimental and harder aesthetic, and together, Spiral Tribe amassed an influential catalogue of mystical, deadly dancefloor weaponry.

As you would expect from a collective led by the mantra of ‘never stop’, the Tribe never officially broke up, and their story continues to this day. But the late ’90s arrival of children caused a gradual dissolution of the collective. Harrison, Carter, Vaughan and several other Spirals continued making music and playing live, and many of the crew reformed in 2011, staging parties and getting involved in community projects. “Despite all the state-sanctioned violence, increased penalties and destruction of equipment, the scene continues,” says Harrison, “with profits from the re-release of Spiral Tribe’s ‘Forward The Revolution’ going to support a project of emergency legal support for free parties attacked by the police in France.”

Spiral Tribe pioneered dance music in the previously rock-centric UK free party scene, kickstarted and provided the musical template for the Teknival movement and inspired a generation of free sound systems across Europe. They also presented an alternative, ethical model of dance music production and distribution, and their anti-commercial/anti-authority/never stop ethos was hugely influential in contributing to the character of the UK rave scene and the European free festival circuit. Oh, and their events brought joy, community and a genuine sense of freedom to countless dancers too.

“We just kept playing, playing and playing... and it’s been 30 years of playing all over Europe and the world, doing illegal parties, clubs and festivals,” Vaughan tells us. “And the thing that still shines beyond anything else is that moment when you’re in a nightclub and suddenly you get those shivers down your spine because the music just hits the spot.”

Carter is low-key about Spiral Tribe’s achievements. We ask him what he thinks their legacy is and he instantly deadpans back, “Ask me when I’m dead!” — before descending into a fit of techno-sprite laughter. It’s funny, but it’s also an entirely appropriate response: it’s not over, their legacy isn’t complete: Spiral Tribe still haven’t stopped.

Listen to an exclusive live mix by R-Zac, recorded live in Třebíč, Czech Republic in 1994, below.