Super Sharp Shooter: photographing three decades of rave with Sarah Ginn

Super Sharp Shooter is the new book from club photographer Sarah Ginn, documenting her work across the ’00s, ’10s and ’20s in capturing dance music culture. Here, Simon Doherty sits down with Ginn to talk through some of the books best photos

Bristol-based photographer Sarah Ginn has spent the last 15 years documenting the night. While you’ve been on the dancefloor, she’s been hovering around the peripheral wrestling with smoke machines and equipment which doesn’t like the humid conditions. All to get the perfect shot. And that she does — during the ’00s, ’10s and ’20s, her work became synonymous with the likes of fabric (where she was photographer-in-residence), the now defunct Red Bull Music Academy, Glastonbury, Printworks, Outlook and many more.

When you put Sarah’s body of work together, you end up with the rich tapestry of electronic music culture that is her new book Super Sharp Shooter. There aren’t many photographers who have captured contemporary electronic dance music culture with quite this range — the chaotic energy of drum & bass, the evanescent hype of the early dubstep scene, the house and techno tribes, the collective joy of festivals, the iconic clubs, it’s all there across 432 pages.

Five years ago, as the Me Too movement was rocking the boy’s club that was (and still is) the electronic music industry, Sarah bravely shared experiences in the scene. “The misogyny and bullying I have had to endure over the last three years should not be something that anyone has to go through,” she wrote on Twitter at the time. “It doesn't matter what you achieve if people objectify you as fair game because you are backstage.”

Five years on, her art has gone from strength to strength, but she still feels these injustices exist in this male-dominated world. “When that whole situation happened to me, I didn't have any framework to hang it on,” she explains to DJ Mag. “Then the [Harvey] Weinstein thing came out. I realised that as a female photographer — this was a very unfortunate thing at the time and it still happens now — I was very popular when I suppose I could have been ‘sexually available’ in inverted commas. But once that was taken off the table, I'm not considered as worthy as a male photographer.”

Ginn’s book — which is sub-titled A Spectral Photographic Journey Through Bass Music — is a collection of over 800 images, many of which have never been seen before. In a statement when the book was announced last November, Ginn said: “I’m looking forward to publishing this book because these actually are my only memories! Research shows that when you take photos it actually affects the way you remember things. So on that note, I hope you all enjoy my crazy spectral journey into sound, the many sights of the rave and everything in between.”

Super Sharp Shooter, is being published by Velocity Press and you can order it here. Below, Sarah talks us through some photos from the book.

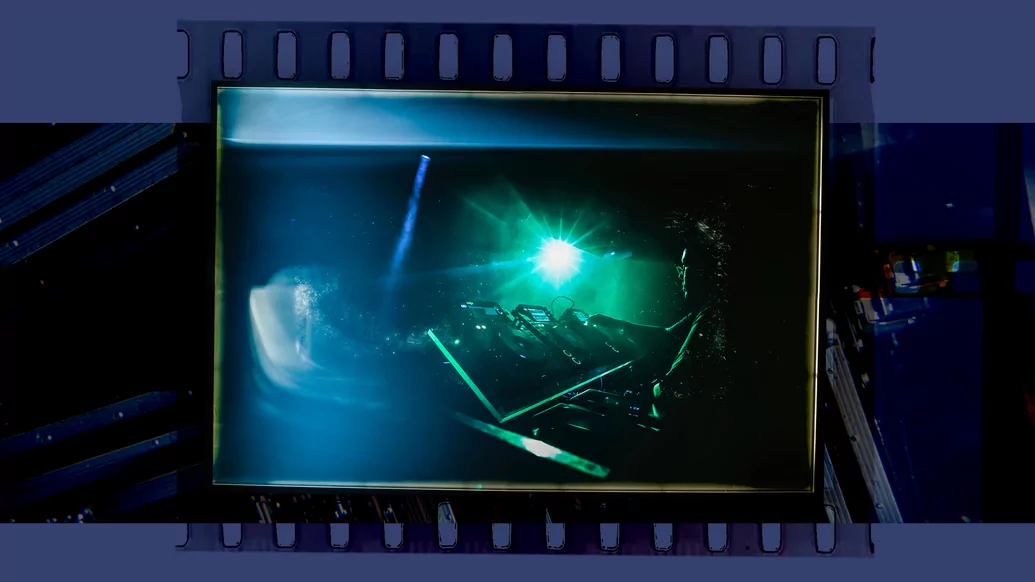

“This is down in Room 2 in fabric. I used a programme that had a retro plug-in. I believe I may have asked for the light to shine in that direction. That’s what I used to do because I knew what worked. So we’ve got this lovely silhouette of him but I just made it look old. I put a lot of light leaks on it and made it look like it was shot on film. It’s not shot on film, it’s a reconstruction of that but it works really well with the colours.

“For a while I did a lot of my photos in a very retro style, sometimes I still do. When I first started at fabric I shot on film for the first year and a half. I worked in a photo lab at the time and I used to steal film from the basement to use at fabric. It was voluntary back then, so I’d bring six rolls [of film], shoot them off and then go and have a dance. I like to hark back to the retro days.”

“This was when a lot of grime nights were being booked at fabric by Tom and Rob from The Blast in Bristol. What I used to love about those nights was the energy; the grime nights were unparalleled, even more energetic than drum & bass nights in a way and they were hectic enough. There were always a million MCs on stage.

“A lot of people say, ‘How are the fabric pictures so good?’ It’s because I worked extensively with the lighting engineers. I made friends with them. I’d go up to them and go, ‘Do you mind not using the red light?’ The trick with music photography, which a lot of photographers do not do, is to communicate with the lighting designers. They want good pictures of their lights and they don’t usually get them. If you work with a lighting designer they’ll do what you want within the realms of what they can.”

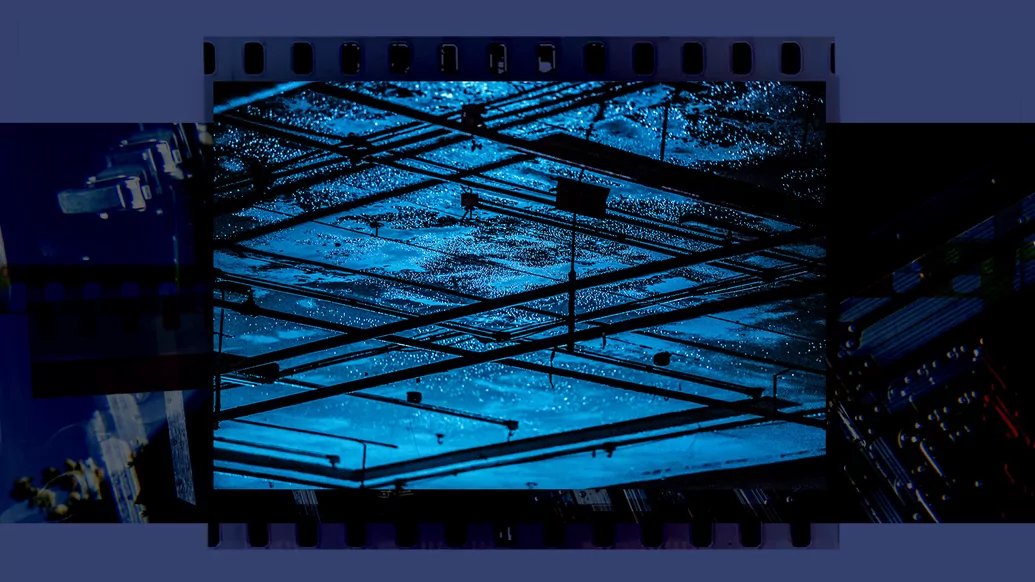

“This is the only one I’ve taken of ‘club rain’ as I call it.”

You don’t see that much now as all the clubs have post-COVID ventilation systems. Shame, that was an indication of a good club.

“Yeah, I agree. I think the atmosphere changes when it’s too comfortable. You want it to be a bit ‘off’, you want it to be a bit sweaty... But that humid atmosphere does screw with my equipment.”

You don’t get clean toilets in an underground club...

“No! You don’t want to come out of a club smelling all clean either, you want to come out feeling dirty. I always try to capture little elements like that because I’m obsessed with buildings and architecture; the sweat and condensation is because [clubs] are often concrete places. That’s all a part of the story as well.”

“This was at South West Four festival in 2012. Skream & Benga had encouraged a stage invasion a few months previously. And so they were really worried about that happening again because it’s, you know, dangerous. So they shut the pit. And there was a very tiny amount of space that I could shoot on the left-hand side. So I was shooting everything from the left; I wasn’t allowed in the pit, I wasn’t allowed behind them, I wasn’t really allowed anywhere. And I took that picture from the tiny space.

“I remember looking at the picture thinking ‘this is fucked’ because there was this huge LCD screen which burned it out and made it heavily overexposed. I didn’t have many memory cards back then so sometimes I would delete stuff on the spot. But I kept it, took it home and put a HDR filter over the top. And something happened to that picture — it just came to life. A happy accident. It’s the combination of just having them in it with no crowd, the smoky stage and they’re almost contained by the monitors. They’re in their own little world.”

“That was the second year that I shot Arcadia at Glastonbury. It was a muddy year if I remember correctly. And at that point, they hadn’t put lighting in the booth to balance the flames and I was not a flash person. So it was really a matter of chance that the strobe went off at that point in time to capture [B.Traits] doing that. That was the one chance and I took it.

“Shooting in Arcadia in the booth is a very hectic experience. You’ve got five minutes, the stage managers lock it down very heavily. In fact, other photographers aren’t generally allowed up into the booth. They like to keep their team very tight, but with regards to that moment it was just really nice to capture her in the spider with her crazy nails.”

“This is why I love taking pictures of crowds: you never quite know what a crowd is going to do. “

The footprints on the stage reflect the intensity.

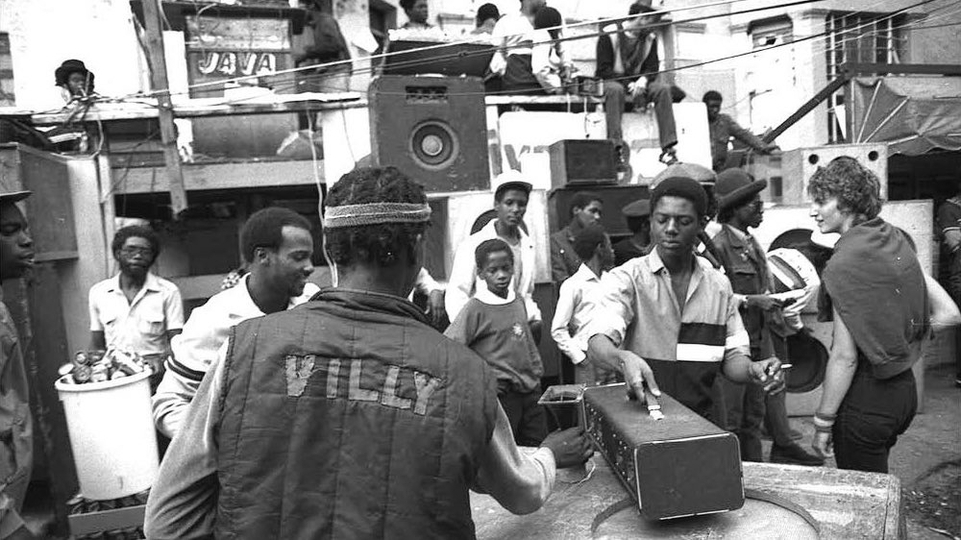

“Yeah, you can see that there’s a million drinks on that stage and they’re all over the stage. That was the riotous Red Bull era that I shot. I shot a lot of Red Bull [events] between the years of 2011 to 2014. They ploughed a lot of money into our scene at that point with those ginormous Culture Clash gigs.”

“Ms. Dynamite was an artist of my youth. So I ended up taking quite a lot of pictures of her because [her track] ‘Booo!’ came out when I was a kid and I love that track. You’ve got so many elements there: you’ve got David [Rodigan] in the background, funnily enough my dad used to work with him as a sound engineer.”

“Andrew was the gentleman of the scene, his persona was very much like that. He was unbothered by everything, nothing seemed to faze him. Very calm. Like one of those elder statesmen that everyone respected. He’s hugely missed not just because of his career but because of this persona I think. Nobody had a bad word to say about Andrew. He was one of those people that just got on with the job, he wasn’t interested in the whole superstar DJ thing at all — he was the antithesis of that.”