Justice: Written in the stars

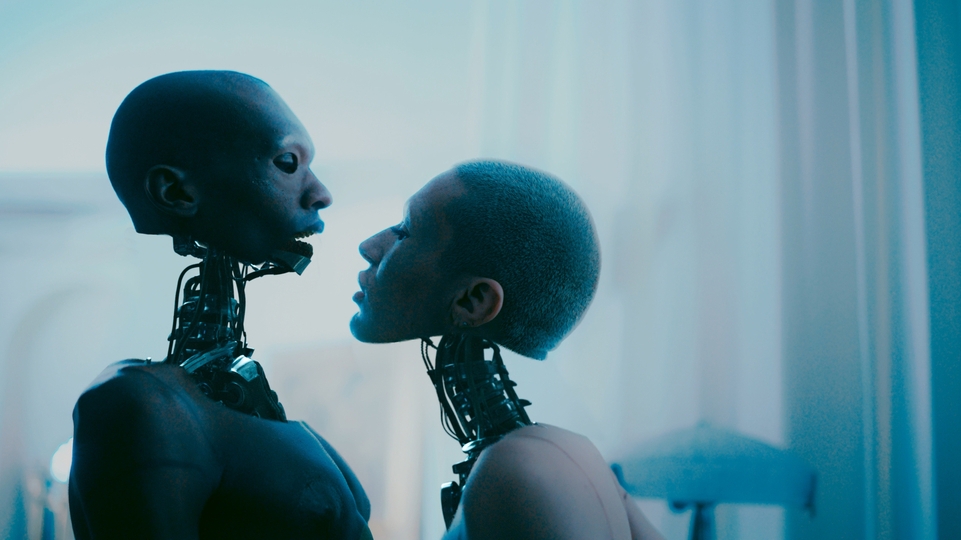

Inspired by the sci-fi movies of their youth, the new concert film IRIS: A Space Opera is the latest ambitious venture by Justice. DJ Mag heads to Paris to find out more

It’s a warm, sunny afternoon in northern Paris, and the streets are bustling with people going about their daily business. Locals line the streets trying to sell everything from cigarettes to corn-on-the-cob to tourists and Parisians alike. DJ Mag is sat downstairs in the La Brasserie Barbès, which is located in the 18th arrondissement in the tourist district of Montmartre. It’s the venue for today’s interview with French duo Justice.

The restaurant has a strong industrial look, with rustic-looking green light fixtures hanging from the ceilings. With our eyes glued on the entrance, an assortment of Parisians make their way in for their morning coffee and croissants, whether it’s businessmen conducting informal meetings or young digital marketers presenting to clients. It’s a quintessential Parisian melting pot, and exactly the kind of place you’d expect Justice to be hanging out.

Gaspard Augé arrives first; he’s dressed in a casual black T-shirt and black jeans, and is wearing a pair of Ray-Bans. Since the duo’s inception, he’s always been known as the quiet one, and it shows, as he moves in a considered, low-key way. He’s clearly a regular, too, as several customers recognise him as he moves through the downstairs of the restaurant. A few pleasantries are exchanged, along with a couple of fist bumps, and he then disappears upstairs.

Twenty minutes later, Xavier De Rosnay arrives. He’s always been known as the chattier of the two, and you can tell, as he walks past us talking on his phone. He’s wearing a black and white varsity jacket, blue jeans, and country music-inspired white shirt.

We’re here to speak about their latest project, IRIS: A Space Opera. It’s a meticulously crafted concert film that tries (and largely succeeds) to capture the band’s retina-searing live show in a new, compelling way. Since the inception of their live show back in 2007, they’ve always struggled to capture the energy of it on film, and have found their previous results to be underwhelming.

“We’ve never really managed to do it,” says De Rosnay, nibbling on a light lunch. “We have a couple of shelved projects. We actually filmed some shows and started to edit them, but it just wasn’t good — so we never released them. Whatever we would do, the YouTube videos from people were always better than what we had done. So, of course, we tried to film the shows with iPhones or whatever, but it just didn’t work — it didn’t feel spontaneous.”

“There’s something about trying to translate the energy on stage onto a film that just doesn’t work,” he continues. “And actually, when we try to think of good examples of a live show that works well on film, we can’t think of many. The ones we do like, for example Neil Young, is because you don’t see the audience, you just see him with a guitar — there’s something about the rawness of the songs that works this way.”

The duo eventually realised that they would have to adopt a different approach. That’s when they made the difficult decision to take the crowd out of the equation. “We thought the solution was to film it in a controlled environment instead,” explains De Rosnay, so they rented a movie studio in Paris for two days and created a sealed environment that they could fully control.

“We have the camera always where we want it to be, at the moment we want it to be, and since there’s going to be no audience, and the film is not going to look like it’s filmed in a music venue. I think it makes people get rid of the expectation of seeing a normal live show. But you hope they see something else, and yeah, it’s an idea that has been 10 years in the making,” says De Rosnay.

Augé often hangs back to let De Rosnay do the talking, but when he does speak he does so with a clarity that’s a stark contrast to De Rosnay’s more meandering explanations. “The thing is, when you go to a proper live show, it’s the appeal of a collective experience,” explains Augé. “It’s part of what makes a live show enjoyable, and this time, it’s maybe a more intimate experience. We just wanted to get rid of all of the frantic side of things, you know, for something very slow and way more contemplative.”

Throughout IRIS: A Space Opera, there’s a strong visual identity that’s been heavily influenced by ’80s science fiction, something that the duo believe is just part of their upbringing. “We’re not obsessed with it [science fiction films],” says Augé. “But I guess it’s more a matter of generations. When you are growing up in France in the ’80s, this is the only thing you had on TV for children, just like space, space, space! And I guess it stayed with us. Also, there is this utopia that we love about science fiction, too — it’s just so impregnated into our brains, and we can’t get away from it.”

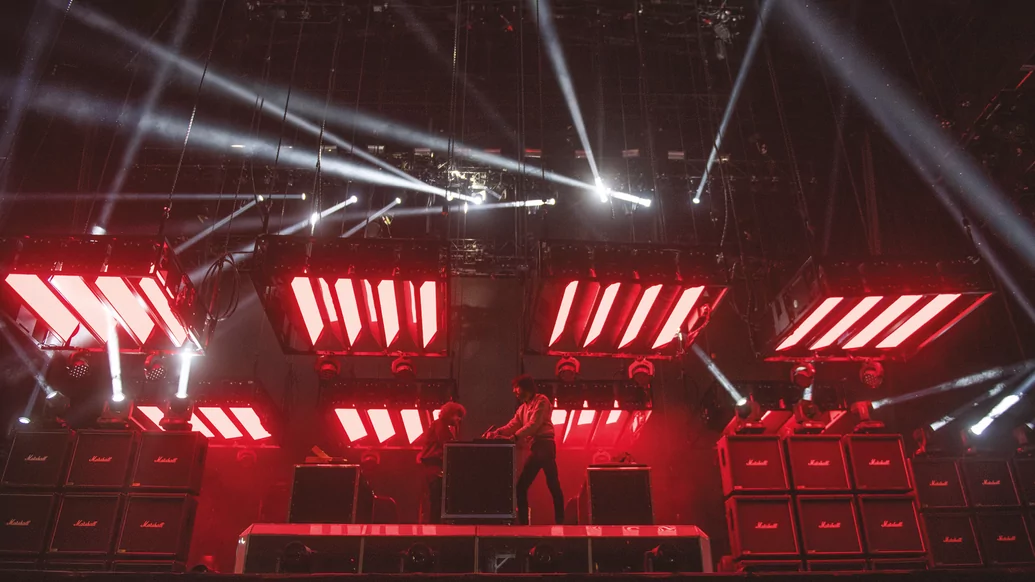

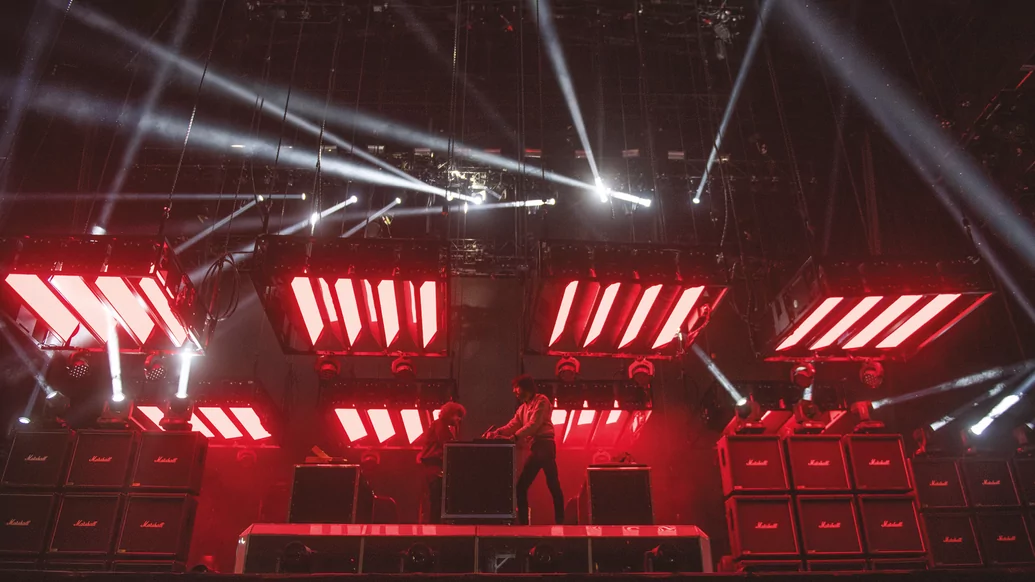

Using slow panning shots, IRIS: A Space Opera captures the majesty of Justice’s stage set-up, which they designed themselves. It consists of a floating structure comprised of 13 moving frames, and each one features four rotating panels of LEDs, mirrors, and warm lights, which offer infinite combinations. With this backdrop, the duo — alongside André Chemetoff and Armand Béraud, the film’s directors — use some of sci-fi’s best camera tricks to capture their stage design in all of its glory for the big screen.

“The thing is, we built the live set-up almost three years ago with references from Blade Runner and Close Encounters Of The Third Kind. The plan was to have cold lights and warm lights, and then the idea of having a flying camera, moving very slowly,” says De Rosnay.

He recalls the first shot from Star Wars as an inspiration for how they wanted to film IRIS: A Space Opera. “You see this small spaceship in the distance, and then you see the other one coming from above... it is because of these kinds of things that we decided to film it in a space which is so absent, and so black. Of course, it looks a bit like space, and then we began to build ideas around this.

“We noticed that the more slowly things move, the heavier they seem to be, and if you see something moving like this [moves his hand quickly], it doesn’t seem as impactful as something moving slowly,” he continues. “So the natural way of filming it for us was to shoot it like a nature documentary, or an old science fiction movie, where you have one or two-minute-long shots, and just have something moving very slowly, like 2001: A Space Odyssey. That’s why we chose the front cover, as it reminded us of this.”

Justice are conscious that not every fan will be able to see the finished film on the big screen, and are already thinking about what will happen once the initial staggered worldwide cinema release comes to an end. They have considered releasing it on Netflix, but in reality, they have far loftier ambitions for their latest film.

“In our dreams, it will stay in cinemas forever,” says De Rosnay. “It would be so cool if it [IRIS] could be shown every Monday in a place with only 50 seats. But at the same time, we have a lot of people who don’t live in areas where it is being played, and they want to see it, too. We recognise that it would be vain to release a record and only print 1,000 copies of it — we don’t like this in 2019. It would be a cool dream, but at the time, what’s the point of doing that?”

“We would like [IRIS] to be kind of exceptional, you know?” Augé agrees. “A bit cult in a way, where maybe it’s only played once a year.”

Challenging their fans

Justice have always had a somewhat distant relationship with their fans, choosing not to engage with them outside of their usual album cycles. The duo’s aloofness is often one of the reasons why they are so revered by their fans, but it is not something that’s done intentionally by the duo.

“We don’t do anything for fan service,” explains Augé. “We just do things that we would like to see if we were fans of Justice. We like things that are heartfelt and generous, too, but most of the time it’s just to please us, and then obviously we cross our fingers and hope that people might like it as well.”

De Rosnay agrees that they aren’t particularly influenced by what their fans might want to see from them. “For me, fan service is a bit cynical. It’s not generous doing an act because you want something back in return,” he says.

“We spend a lot of time doing things on a big scale. We know that, in the end, this is not for everyone, and that it has no purpose other than being something that we think is cool. When we DJ, for example, we know exactly what we need to play for things to work. But we always find it more interesting to create that window: where we can play two or three tracks that challenge them, even if it’s music that’s impossible to dance to; and then you come back on something easier,” he explains.

De Rosnay believes that their role as artists is to challenge the audience, not to just give the fans what they want. “The best parties we used to go to would happen around here, like 10 or 15 years ago. These two guys would playing all night long, playing new wave, punk, or really hard stuff, and we were not dancing. Nobody was dancing. But the music they used to play there? We always remember it. It’s ok to go to a party and dance — it’s fun, but what do you take home with you at the end? Not many things, I think.”

Justice are acutely aware that they don’t use social media in the same way as many other artists do. “We don’t provide anything behind the scenes of our lives, so people don’t get to see where we stay in a hotel, or what we are eating for lunch, or whatever,” De Rosnay says. “So we are not using it in the right way. The traffic on our social media is quite low, but it’s not something we are interested in anyway.”

But they do have strong views on the role of algorithms and streaming platforms, and how music taste is being engineered on platforms like Spotify. “It’s like AI has already won,” proclaims Augé. De Rosnay largely agrees. “Even when it seems to be good, when the intention is good and the algorithm redirects you to things that you like, that sound similar, it’s good in a way — but at the same time, everything’s made to put you in this complacent position.”

Justice are acutely aware that they don’t use social media in the same way as many other artists do. “We don’t provide anything behind the scenes of our lives, so people don’t get to see where we stay in a hotel, or what we are eating for lunch, or whatever,” De Rosnay says. “So we are not using it in the right way. The traffic on our social media is quite low, but it’s not something we are interested in anyway.”

But they do have strong views on the role of algorithms and streaming platforms, and how music taste is being engineered on platforms like Spotify. “It’s like AI has already won,” proclaims Augé. De Rosnay largely agrees. “Even when it seems to be good, when the intention is good and the algorithm redirects you to things that you like, that sound similar, it’s good in a way — but at the same time, everything’s made to put you in this complacent position.”

“‘Success is a collective hallucination,’ I think Bowie said that,” says Augé, on why the duo have seen success over the last 16 years. De Rosnay adds, “At some point, you don’t know why, but you make something that so many people are interested in at the same time, and there’s no real formula for this. But now, with algorithms and stuff like this, there’s a visible part of the formula.”

De Rosnay doesn’t think the talent can’t break through anymore, though. Quite the contrary. “When I see bands like Phoenix and Tame Impala having huge success, it warms my heart. Because it’s not a success that has been decided by an algorithm. It’s success that has been decided on quality, and been recognised by a huge amount of people at the same time for some reason. This is still a bit of a mystery. Every time one of those bands breaks out, like Mac DeMarco, it’s amazing — it gives me hope for the future.”

Money, Money, Money

It’s clear that the duo aren’t driven by money or fame. They see their success as a by-product of their art. They recently scooped a Grammy for Best Dance Recording for ‘Woman Worldwide,’ which makes up the music for IRIS: Space Opera. It was a controversial decision. Many in the underground dance music scene feeling either SOPHIE or Jon Hopkins should have won. This doesn’t seem to bother the duo, though.

“Of course, we were surprised that we won it,” says De Rosnay. “We thought that someone else would win it, but you never know what is going to happen.” It’s a moment that the duo are immensely proud of, and the whole occasion is something they look back at fondly.

“You never really know why you won,” explains De Rosnay. “We feel that it is one of the most honest awards. You can’t see the strings that are being pulled behind the scenes. I think it’s still very legitimate. Maybe it was a way of acknowledging the place we occupy in the dance music scene. Maybe it’s just people who like the record. Anyway, I think it’s useless to try to know the reason why, but yeah, we were very surprised.”

Augé also looks back at the ceremony with fond memories. “Actually, the best part of it is that you don’t know in advance. You don’t know until you are there and they call your name.” Awards aren’t something that the duo want to be reminded of all the time though; they’re more for the team behind them, that helps bring their ideas to life. “Xavier doesn’t actually like awards at home,” reveals Augé.

“Yeah, they are at the office,” De Rosnay admits. “I don’t want to work at home and see all those things. For me, it’s like having your picture on the wall — it just doesn’t make sense. It’s cool to be narcissistic, and we are all narcissistic a bit. But for me, this is too much of a show-off. And if you have guests at your home, it’s not something you want to put in their faces. In an office it is perfect, it’s a place of work, where you have clients, or whatever, it all makes perfect sense. But at home, it’s just too much for me.”

The duo do come across as genuinely grateful for the success they’ve had, but they also feel that their lives haven’t changed that much since they started making music some 15 years ago. “It’s funny, the life we lived before all this when we were graphic designers, it wasn’t that different than the lives we have as music makers today,” De Rosnay says.

“Because being graphic designers, we were already masters of our schedules, we were already working with things we liked, we were already picking the projects we wanted to work on, so it’s not that different. Of course, we have a better life now, but it was not so different. We don’t run after money. We don’t play 300 shows a year. It’s a choice, you can’t make this choice and then complain about it. We’ve never felt the need to think, ‘We need to play like this because this is what’s happening,’ or whatever. If it works for us and we want to do it, then we do it, and we, ‘knock on wood,’ hope we can continue this in the future. But honestly, it’s not the hardest job on earth.”

Breaking America

Justice have always had an affinity for playing in America, and they’ve always made a point to play in the US for each album tour. “I love playing in the US,” explains De Rosnay excitedly, as his eyes light up, “especially the festivals. We like Coachella. We think the hype is deserved. But we love to also play in the UK where people are...” “Responsive,” Augé interjects.

“You rarely play and nothing is happening,” De Rosnay adds. “I don’t have many memories of playing in the US and nothing happening, either. In the US they own the concept of entertainment, so maybe that’s why people are so into it, but in the UK they own the concept of partying, which is a bit different, but in the end — it produces the same kind of results.”

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that Justice helped America rediscover its love of dance music. When they burst onto the dance music scene in the mid 2000s, they were acutely aware that they were laying the groundwork for dance music to flourish across the US once again. “Led Zeppelin was my favorite band when I was growing up,” says De Rosnay.

“But they were whitewashing other rock music, you know. Because their music is heavily inspired by black music, but it’s not something unique to dance music, it happens in other forms of music, too. You have people putting the bricks on something, and then you have people taking them and making a forty-story building out of them — there’s nothing you can do about that. It’s the natural order of things, it’s the same with rap, and whether you think Skrillex invented dance music, or that Drake invented rap — it’s not really about white or blackwashing, or whatever, it’s just the natural evolution of things.”

And Augé agrees: he believes the very essence of creativity is rooted in inspiration. “Nobody comes from nothing, so I guess it’s the same for every genre of music, or any form of art, everybody is inspired by something older, and nobody creates out of thin air."

The Pedro and Ed Banger effect

One constant that has remained throughout Justice’s meteoric rise has been Pedro ‘Busy P’ Winter, the founder of Ed Banger Records and former manager of Daft Punk, who has guided the duo throughout their career. And the one word that De Rosnay uses to describe him?

“Chill,” De Rosnay says bluntly. Augé agrees, adding, “The great thing about Pedro is he’s managed to keep his very child-like teenage enthusiasm. So he’s always excited to try new stuff. Like for example, we did some work with a classical orchestra for some covers — he always comes up with ideas like this. Now he’s into publishing books, which is cool.”

Their relationship is one of trust, which is born out of giving the duo absolute freedom when it comes to making music. But Pedro will always tell Justice if he doesn’t like something, and that almost had tragic consequences for one of the duo’s most revered tracks.

“One of the things we’ve been given is 200 percent freedom by Ed Banger in what we are doing,” De Rosnay says. “For example, when we released ‘Waters Of Nazareth,’ Pedro didn’t like it. He said: ‘It’s not my cup of tea, I don’t like it.’ But he was still 100 percent behind it. The label was treating it as if it was something important. It’s the best thing to have that support. I don’t know many record labels that offer that to other people.

“He’s a very enthusiastic person and of course we can’t help but question ourselves when he says he doesn’t like something,” he continues. “But actually, what happened is we listened to him and we were ready not to put the track on the EP. And then one day, DJ Mehdi came to our place and we played him the song, and he was like: ‘What are you doing? This is the best thing you have ever done, you can’t not release it.’ So, the day before the mastering we finished it during the night and sent it to be mastered, and it was released as is.”

So what’s next for the duo? Well, they tell DJ Mag that they haven’t begun working on their next album, but it’s always something that’s in the back of their minds and, just like any artist, they’re always thinking about it, what it might sound and look like.

“After every tour, we are thinking, ‘What are we going to do next? It’s gonna be impossible,’” explains De Rosnay. “And then we find some solutions. We tend to think, and hope, that the solution of making it better is maybe to have fewer things, maybe not twice as much but instead twice as less. We are always thinking about the future. We have folders in our telephones or computers, or whatever, because it might be useful. It could be anything. It can be just the light of an image or it could just be a building.”

They’ve always taken their time when it comes to making music, and don’t put an arbitrary time-frame on their creative process. “When you take 18 months to make something, you are going to use the whole 18 months, and if you’ve got three months, you’ll take three months, you will always use that time to experiment,” explains De Rosnay on how they go about creating music.

“So, we can’t help but try all the possibilities we can see or entertain. But even if you have an idea at the beginning and it turns out to be that one — you’re going to still experiment and explore. We can’t help it.”

Gaspard agrees. “I guess the main difference with Europe and the US is that we don’t have that industrial spirit about making a record, you know? With the best singers, or the best drummers. I guess great records are made the US way, but for us, we like to take a more craft-like approach to making a record, and we like to take our time.”