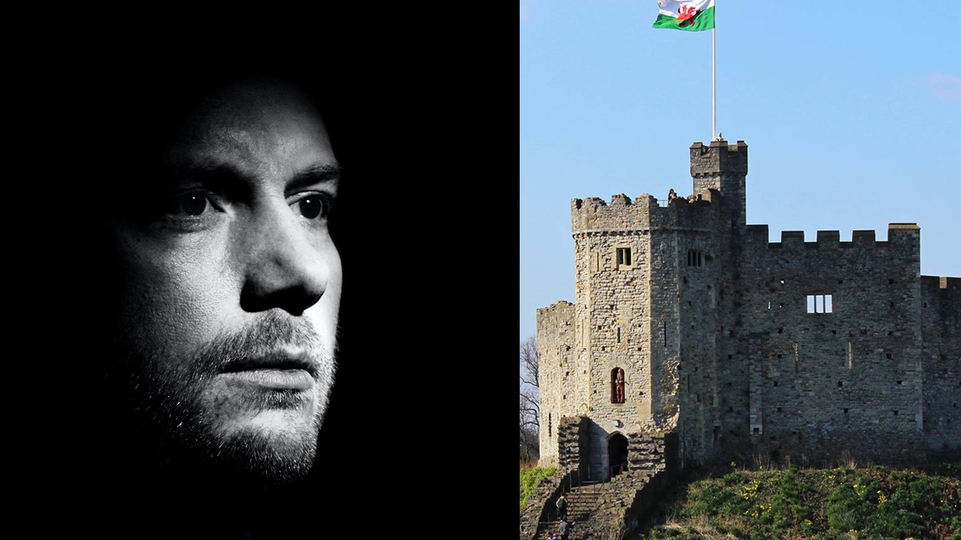

How Wales is reclaiming its place in electronic music history

Since electronic music’s early days, Wales has produced incredible artists, but is often overlooked in its history. Here, Dave Jenkins celebrates the unsung heroes of the scene and meets a new generation putting their national identity at the forefront of their music

Croeso i Gymru, a land rich with music history. Home to the oldest festival of music and culture in Europe (the Eisteddfod, 1176), Marconi’s first ever radio transmission (from Flat Holm Island to Lavernock Point in Penarth, 1897), the oldest record store in the world (Spillers Records, 1894), and arguably the first superstar DJ in the universe, Sasha, who was boldly described as the “first DJ pin-up” (Mixmag, 1991).

Wales is home to a whole slew of legacy acts: MC Eric from Technotronic, Nomad, Underworld and K-Klass all have Welsh roots. It’s birthed headliners from across the spectrum, such as Kelly Lee Owens, High Contrast, Overmono and Jamie Jones, respected underground beatsmiths like Quartz and Don Piper, long- standing UK garage ambassadors like Fabian Dubz and Richie ‘ViBE’ Vee, and techno professors like Alan Palmer (often known as A.P) and Sam Watson. That’s before we even get to world class festivals like Gottwood and Freerotation, the latter of which is an event so special it’s where Sebastian Mullaert launched his legendary Circle Of Live concept.

The more you dig, the more you realise just how much dance music is peppered with Welshness. Great tales of cult legends ring out from south to north; there’s the sorely missed Stagga (RIP), a man behind many Cardiff community-based projects, who made beats so far-out and sleek they were regularly spun at LA bass church Low End Theory. Stagga was connected to other hugely respected underground Welsh beatmakers like Elmono and Darkhouse Family — aka Don Leisure (who was previously known as d&b artist Jamal) and Earl Jeffers (who has a sprawling discography across his Metabeats and Chesus aliases).

Meanwhile, up north, there’s the enigmatic Leif, whose explorations in techno, ambient and Foley manipulation remain timeless and matchless. Or Bangor-born Koreless, who gave the world the head-bendingly delicious album ‘Agor’ last year and was recently spotted producing for FKA twigs. Congo Natty is half-Welsh and spent many summer holidays at his maternal family home in Llandrindod Wells. Cult clubbing movie Human Traffic was based and filmed in the Welsh capital Cardiff, and North Wales town Machynlleth (home of Owain Glyndŵr’s rebel Welsh parliament of 1404) is twinned with Belleville, Detroit, the birthplace of techno. Welsh artist Ffrancon wrote an album-sized ode to this link last year in the form of ‘Gwalaxia’. Even the Welsh Labour Minister of Climate Change has links to electronic music — the right honourable Julie James is Aphex Twin’s sister.

For a country of 3.19 million — a population a third the size of London’s — Wales makes serious noise. Yet its role and influence in electronic music hasn’t been documented in much detail; it’s seldom mentioned in wider discussions of UK rave culture and many of its protagonists haven’t been celebrated at the right volume. Paul Lyons is a great example. Owner of the Soul Good and Headfunkt labels, he was an integral part of the UK’s acid house movement and the first mixed- race DJ to perform in a Welsh city centre venue and play house music to mixed crowds. Regularly driving down to London for the freshest new music, he was the Cardiff equivalent of pioneering selectors such as Mike Pickering from Manchester’s Haçienda or Colin Hudd from London’s Spectrum.

He moved in the same circles and broke down the same barriers in a UK capital city, yet his name isn’t known on the same level outside of the soulful house movement in which he produces. “I don’t think there are many roads out of Cardiff,” suggests Paul. “If you’re a big DJ in a city like London or Manchester you’re internationally known. In Cardiff, that just wasn’t the case for a lot of residents in the city.” He now runs community studios across low-income areas of Cardiff called Sound Progression, and is dedicated to giving young Welsh talent a solid platform. His most recent initiative has been helping local rappers form a hip-hop band and this month he’ll take them to New York.

"People would say 'Wow, you’re from Wales and you do something other than farming?' It’s like we’re just big green fields full of daffodils, sheep and rugby — that’s not the Welsh identity.” - MINAS

DJ Guy is another renowned Cardiff artist who’s been active since the late ‘80s. An integral member of the South Wales grassroots movement as a teacher, Guy’s international exposure only began after he released his debut record in 2014, put out music on Hypercolour, and scored a Boiler Room set a few years later at the age of 46. With a strong community focus and a dogged dedication to their craft, artists like Paul and Guy represent the true Welsh electronic music mainframe. Other examples include Welsh hip-hop pioneer DJ Jaffa, bands like dub/funk fusionists Llwybr Llaethog, and long-standing house producers like Justin Stride and Sean McCabe — all renowned within their fields, but arguably less well-known than their English counterparts.

“We’ve got big neighbours,” says Don Leisure. “If you’re in North then you’ve got Liverpool or Manchester. If you’re down south you’ve got London or Brighton. There’s Birmingham, there’s Bristol. We’re far out over here, there’s not as many people passing through.”

Geographical challenges aren’t the only ones Welsh electronic music artists and communities face when it comes to reaching ears beyond the border. They’re often overshadowed by stadium-filling Welsh indie bands (Stereophonics, Manic Street Preachers, Catatonia) , and culturally and historically there’s a whole load more to unpack — so much so that some Welsh artists don’t reveal their location in fear of what it might do to their careers.

“I had fears that it might hold me back because of the attitude of people, being the butt of jokes, being a small island attached to a bigger mainland,” admits 28-year-old Minas, a maverick genre-fusing singer/producer, who makes music for the new jilted generation that ranges far beyond his Valleys upbringing and Cardiff location. Sitting somewhere between Idles and Mike Skinner, his rage simmers visibly as he observes life growing up in a low income community, where alcoholism, addiction and crime are rife. “Recently I’ve just thought, ‘Fuck it, let’s go for it’,” he continues. “My time in England, going to university, reinforced that. People would say ‘Wow, you’re from Wales and you do something other than farming?’ It’s like we’re just big green fields full of daffodils, sheep and rugby — that’s not the Welsh identity.”

“All I ever hear is Gavin & Stacey jokes when I speak to English people,” adds singer and songwriter Niques. The Cardiff- based 23-year-old has established herself with rich, soulful clarity this year through solo releases and collaborations with the likes of d&b acts Sam Binga and Foreign Concept. “They got no idea what it’s actually like to live here. We ain’t going to the seaside every day I can tell you.”

Minas and Niques capture the essence of the Welsh experience. What is often passed off as harmless UK cross-border banter actually highlights a complex that’s centuries deep. The Welsh mother tongue is rooted in an ancient Brittonic Celtic language that dates back over 4,000 years. Outlawed among the ruling class by Henry VIII in 1536, it was banned in schools and public administration for centuries and was only legally recognised 80 years ago in 1942.

The road networks tell a similar tale: Wales has just one major motorway across part of the south, and any journey from north to south can take the best part of a day by train, amplifying a historic disconnect between the two regions of the country. Even the etymology of the name Wales comes with very negative connotations, as it’s derived from the ancient Saxon word ‘walha’, which translates to foreigner or outsider.

“We weren’t taught that in school!” exclaims respected singer/ producer/composer Kelly Lee Owens. Another shining beacon of unique and forward-thinking Welsh electronica, she grew up in Rhuddlan, North Wales. “The potency of that! Does it carry resonance? Does that make us feel like outsiders? Can we reclaim that? Should we say Cymru? These are the discussions that we need to have when it comes to identity.”

A redefinition of identity and what it means to be Welsh in the 21st century is a consistent thread in all the interviews we conduct for this feature. Even down to successful TV shows like Gavin & Stacey and bands like Goldie Lookin Chain, there’s a sense that a lot of Welsh creative output panders to outdated clichés that don’t really reflect what Wales is capable of artistically.

Minas and Niques are part of a new generation of artists who are reclaiming the narrative, and in no other genre is this more evident, and rapidly moving, than in grime and rap/MC culture. Often referred to as the Welsh MOBO movement, a new swathe of vocalists are telling their own stories and giving their own perspectives.

“My Welshness is part of who I am, it’s part of my story, it sets me apart from my peers on a UK aspect,” considers Mace The Great. Alongside other prominent voices in Welsh rap — such as Juice Menace, Deyah, Lemfreck, Luke RV, Kiddus, Local, Razkid, Marino, Sage Todz, Benji Wild, Fig., Ez Rah, The Honest Poet, Fearnquest and so many more — Mace is at the forefront of a thriving new wave. His lyrics reflect his roots and the unique challenges young Welsh adults go through. “You don’t see many people who’ve crossed the threshold from Wales to a wider scene. There aren’t many of us representing — it’s something I wear on my sleeve wholeheartedly.”

Mace explains how he’s been invited to move to London on many occasions, but refuses to do so. “If we all move to London, what’s going to happen here?” he asks. “It’s easy to get Londonised. I’m a Cardiff boy, I’ll always be a Cardiff boy. I don’t want to lose an ounce of that. I’m proud of that and I want to help this grow to the point where organisations like the BBC stop and say ‘Why haven’t we got a 1Xtra in Wales? We need a 1Xtra in Wales’.”

Minas has decided to keep his studio base in the Welsh capital, too. “I’m working with people who want to talk about the same things as I do,” he states. “So why would I go to another place where people are talking about something else?”

In a post-Covid, financially-ravaged, late-stage capitalist world, is migration to a big city really that sustainable or appealing anyway? For some artists, the move has gone the other way. Once a topline singer for hire, now an experimental producer and alt-pop artist, Rachel K Collier moved back home from London to her Swansea stomping grounds during lockdown. She’s not looked back. “Would I go back to London?” she asks. “I don’t think so. I have more time here, more space and a beautiful view. No one is in a rush. It’s so much better for the head space.”

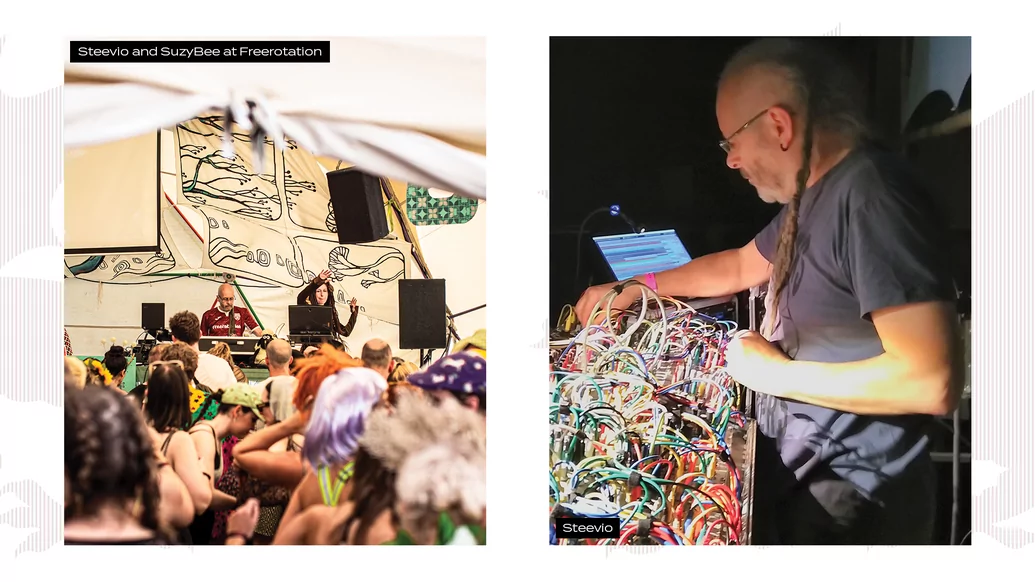

This is another point raised in many of our interviews — Wales is much more conducive to a creative lifestyle. It’s cheaper, less intense, and it gives artists the room they need to create something of their own. Many have moved here as a result and now call Wales home. The story of Freerotation founders Steevio and Suzybee is perhaps the most fabled tale of all. Originally making hard acid techno, Steevio’s music changed when he came to Wales, thanks to the influence of friends and fellow experimental spirits such as brothers Tom and Joe Ellis and Leif.

“We don’t have that many distractions here,” says Steevio, who was on the free festival/ traveller circuit in the ‘80s and early ‘90s. He first came to Wales in 1991 for a famous Spiral Tribe rave in Bala. Similar to the legendary Castlemorton rave a year later, it attracted tens of thousands of revellers and was a big watershed moment in Welsh dance music history.

Steevio found himself returning again and again before meeting Suzybee and settling down in mid-Wales. “Nowhere to go. No pubs. Not many visitors. You have a lot more time on your hands,” he continues. “When I lived in Newcastle you couldn’t get lost in anything — there’d be someone at the door every 10 minutes. Here you’ve got all the time in the world to be experimental and try things out.”

“When I lived in Newcastle you couldn’t get lost in anything — there’d be someone at the door every 10 minutes. [In Wales] you’ve got all the time in the world to be experimental and try things out.” - STEEVIO

This sense of space has given Steevio and Suzybee the freedom to create a truly unique culture and community. Freerotation began as a distribution network of Welsh labels, but is now an annual gathering that’s one of the most sought-after tickets in electronic music. With a strong local focus and even stronger policies on sustainability and community, international artists don’t just fly in for their set and fly back out again, they take part in the whole weekend and play other domestic shows. Steevio’s son, the DJ known as Mötas, is following in the family tradition, employing a similar community concept at his own party series, Ymuno (which means ‘to join together’), further west in Aberystwyth.

A local focus is something Steevio and Suzybee believe all promoters will have to embrace as we work towards a carbon-neutral future. It’s a discussion that was rife during lockdown, but seems to have been conveniently forgotten since the world opened up again — the idea of championing local talent and cultivating local scenes that are sustainable, making gigs affordable for punters to attend without financial worry and affordable for promoters to be able to take risks. It’s something that Wales has thrived off in the past (and a culture that led this writer into a life in music). In the ‘90s and 2000s, South Wales DJs and clubbers spent more time between cities and a more active free party network.

“I know things are different now and we discover a lot more on social media these days, but it really did feel more like a culture before,” explains garage DJ Fabian Dubz, an artist who’s been flying the Welsh flag since his early tunes were championed by Richie ‘ViBE’ Vee on BBC Radio 1Xtra. “You’d step outside of your door and you could feel it. It was more culturally involving. And I remember being in clubs with a much wider age range of people. I’d say it’s more hidden pockets now. And a lot of that is simply down to a lack of venues.”

It’s a problem all Welsh towns and cities suffer from: a distinct lack of venues and even less support from authorities. One sector where this is particularly evident is the LGBTQ+ community. Once famous for its thriving network of queer venues, South Wales’ queer community has unfortunately lost many clubs in recent years.

“It’s challenging,” agrees Barry-based DJ and local legend Butch Queen. He uses the Welsh ballroom community’s struggle to find a consistent venue as an example of the challenges faced when trying to build a hub for people to unite around. “There are a lot of amazingly talented queer creatives working in South Wales, we’re just trying to find spaces that are safe. Venues rarely come up and when they do, they don’t last.”

“I think a lot of that is down to rising costs. The council seem more interested in making a quick buck instead of investing in culture,” agrees Lloyd Best, echoing the feelings of the wider independent music scene, which has seen more club and venue closures in the last few years than any other time in Welsh music history. Lloyd is best known as Dead Method. A forthright voice in the capital’s alt-pop sound, he feels a similar way about the support of queer musicians in the city. “I think it’s poor, really. I don’t think we’re given enough opportunity to shine.”

Just a few months ago, Lloyd released his debut Dead Method album ‘Future Femme’. A vibrant, pop-addled adventure, it’s one of the most exciting albums released in Cardiff this year and has already been nominated for a Welsh Music Prize.

“That’s what spurred the thread of the album,” he continues, “not feeling valued as a queer person and addressing the discrimination we face. There are many talented queer artists in Wales and I don’t feel they’re given their flowers often enough. I wanted to start the conversation with the album and I feel I’ve done that.”

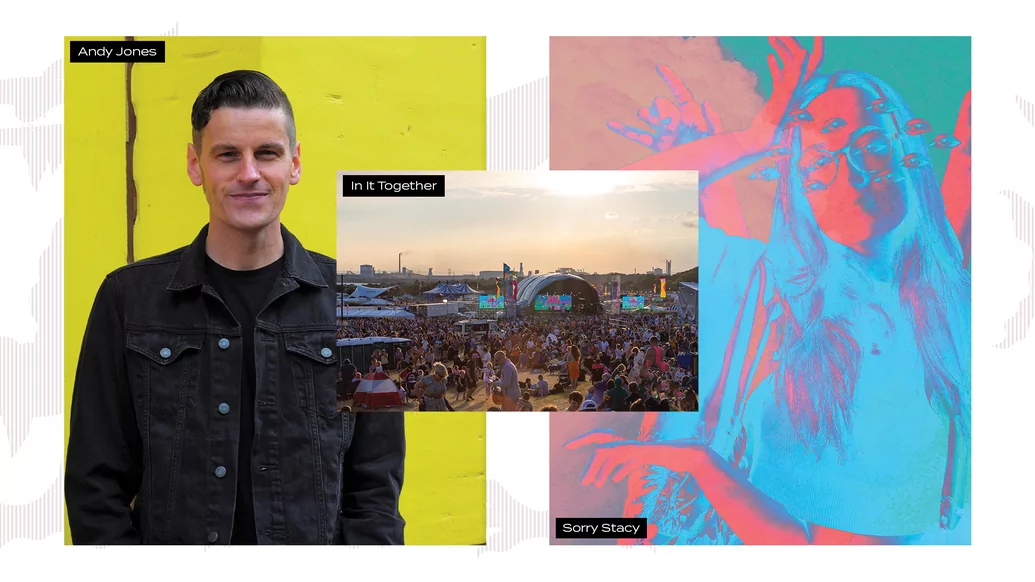

Alongside kindred queer alt-pop spirit Willetts, Lloyd’s sound is a key flavour in the emotionally charged, technicolour sound that’s currently sizzling out of Cardiff right now. Other artists putting the city on the map include the provocative Kitty, the versatile Maditronique, and Sorry Stacy. Mirroring Steevio’s feelings when he first visited Wales over 30 years ago, the latter is attracted to the country’s energy and sense of creative space.

“The mentality is different here — slower, in the best way. You can stop and smell the flowers,” smiles Stacy (real name: Anastassia Svet). A Russian/Ukrainian artist raised in Estonia, Stacy moved to Cardiff to study game design four years ago, but has now put down roots as an artist and is at the forefront of the city’s thriving and exciting alt-pop sound. Largely operating out of a small arts bar Porter’s, she’s quick to credit the influence of Cardiff on her direction and inspirations.

“I got really inspired by the grassroots music here, I switched courses and it was a decision I’m glad I’ve made,” explains Stacy, whose new EP ‘The Fifth Stage’ is a powerful exploration of depression and grief told in the most bittersweet way. “This place has given me motivation. I’ve been making music since I was 11 and studying piano since I was eight, but I never considered putting music out or performing or showcasing music before I came to Wales.”

Stacy’s first performance was at an event called Focus Wales, an initiative that brings everything discussed in this feature together. Established in 2010, Focus is a three-day programme of concerts, panels and showcases that takes place in Wrexham. It’s a chance for the Welsh music community to engage with the wider world, connect and collaborate with each other, and learn vital industry skills. The next event takes place in May 2023.

“When I was a teenager I was told there was no chance of a music career and I should apply for a job at the factory,” says Andy Jones, Focus co-founder. “There’s definitely a sea change for the better. People have a better understanding of what the industry is and how many opportunities it has.”

Andy highlights how the opportunities are growing year on year, and how Focus is part of an expanding network of Arts Council-funded initiatives — such as Beacons Cymru and BBC Cymru Wales’ Horizons / Gorwelion — that exist solely to champion and empower Welsh talent and break down barriers for artists in the most rural corners of the country, not just the more populated cities in the south.

Other organisations doing great work include Ladies Of Rage, a collective working towards diversity and opportunities for women and non-binary artists across Wales, and Larynx Entertainment, a crew who are actively joining the dots between North and South Wales, bringing artists from all parts of the country together.

More and more initiatives like these are establishing themselves as Wales finds its voice and starts to fill new spaces post-Covid. There are new festivals too; In It Together launched this year in Margam, Port Talbot. With a capacity of 40,000, it’s one of the country’s largest festivals, with an ambition to eventually become “the Glastonbury of Wales”.

There, homegrown acts share the stage with international headliners, another encouraging sign that Wales is developing its own platforms for Welsh talent. “There’s so much talent here it’s phenomenal,” says Sam Southam, a member of the Move Together team behind In It Together. “The plan is to keep it Welsh, keep it friendly, keep it community and build, build, build. When the next local success like High Contrast comes along, there’s an infrastructure and a solid means to support them.” Judging by the wealth of talent coming through right now, that’s already happening.